Nationalist Rhetoric in Australia and New Zealand in the Twentieth Century: the Limits of Divergence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism and Human Rights This Page Intentionally Left Blank Nationalism and Human Rights

Nationalism and Human Rights This page intentionally left blank Nationalism and Human Rights In Theory and Practice in the Middle East, Central Europe, and the Asia-Pacific Edited by Grace Cheng NATIONALISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS Copyright © Grace Cheng, 2012. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2012 978-0-230-33856-2 All rights reserved. First published in 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States – a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-34157-3 ISBN 978-1-137-01202-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9781137012029 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nationalism and human rights : in theory and practice in the Middle East, Central Europe, and the Asia-Pacific / edited by Grace Cheng. p. cm. 1. Human rights—Political aspects. 2. Human rights—Political aspects—Middle East. 3. Nationalism—Middle East. 4. Human rights—Political aspects—Europe, Central. 5. Nationalism—Europe, Central. 6. Human rights—Political aspects—Pacific Area. 7. Nationalism—Pacific Area. I. Cheng, Grace, 1968– JC571.N33265 2012 320.54—dc23 2011040451 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. -

Fall Fundraiser: a HUGE Thank You to Everyone Who Participated in the Fall Fundraiser! We Will Have Final Sale Numbers in the Weeks to Come

Wednesday Letter: October 5th, 2011 HOME AND SCHOOL NEWS: Fall Fundraiser: A HUGE Thank you to everyone who participated in the Fall Fundraiser! We will have final sale numbers in the weeks to come. The Final pig races will be this Friday, October 7th at 2:30 in the gym. At that assembly we will also announce the top three sellers and the top selling class! If you have any questions, or concerns, please contact Bernadette and Brian Miller at (402) 738‐8951. **ALSO please remember the delivery of the sale items will be November 3rd. Times will be announced soon, so keep your eyes posted. If you are interested in volunteering that day, please contact Bernadette or Brian, Volunteer Help Needed: Bridgett Laney, our school nurse, is looking for people to help with the Health Screenings on October 18th from 8:30 – noon. No health care experience is required. We are screening grades 1‐6 and 8th so we need all the help we can get! Please contact Heather Weddle at [email protected] or (402) 598‐5257. Calling all chefs: Home and School is putting together a St. Mary’s cookbook! Start thinking about your favorite recipes and keep watching the Wednesday letter for details!! Hyvee Smartboard: Hy‐Vee Smart Points began Saturday, October 1st and runs until noon on December 30th. 1. Customers earn 100 points, via Catalina coupon, for every $20 they spend on Procter & Gamble products. 2. Customers receive 100 additional points when they purchase two(2) or more Sara Lee Fresh Bakery products in the same transaction as the qualifying $20 Procter & Gamble purchase. -

Dunera Lives

Dunera Lives: A Visual History (Monash University Publishing) by Ken Inglis, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter with Carol Bunyan Launch Speech, National Library of Australia, 4 July 2018 Frank Bongiorno Good evening. I begin by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet, the Ngunnawal people, and pay my respects to their elders, past and present. And, of course, I acknowledge members of the Inglis, Turner and Dunera families. Dunera Lives: A Visual History is a result of the historical project to which Professor Ken Inglis devoted the last years of a long and fruitful life as a historian. It is also the product of a great friendship between the co-authors; between Ken and Jay Winter, stretching back many decades, and between Ken, Jay and Seumas Spark, one of more recent vintage, but the bond between Ken and Seumas more like kinship than friendship in Ken’s final years. It is testament to Ken’s own gift of friendship that he was able to bring together these fine scholars to research and write Dunera Lives and, with the help of the excellent Monash University Publishing, to see it through to completion. And as explained in the general introduction, the book has benefited enormously from the continuing research of Carol Bunyan on the Dunera internees. I’m sure you will agree, one you’ve had a chance to see it and, I hope, to buy a copy, that Dunera Lives: A Visual History is a remarkably beautiful volume. Less obvious, until you’ve had a chance to begin reading it, will be that it is also both meticulous and humane in its scholarship. -

Government and Indigenous Australians Exclusionary Values

Government and Indigenous Australians Exclusionary values upheld in Australian Government continue to unjustly prohibit the participation of minority population groups. Indigenous people “are among the most socially excluded in Australia” with only 2.2% of Federal parliament comprised of Aboriginal’s. Additionally, Aboriginal culture and values, “can be hard for non-Indigenous people to understand” but are critical for creating socially inclusive policy. This exclusion from parliament is largely as a result of a “cultural and ethnic default in leadership” and exclusionary values held by Australian parliament. Furthermore, Indigenous values of autonomy, community and respect for elders is not supported by the current structure of government. The lack of cohesion between Western Parliamentary values and Indigenous cultural values has contributed to historically low voter participation and political representation in parliament. Additionally, the historical exclusion, restrictive Western cultural norms and the continuing lack of consideration for the cultural values and unique circumstances of Indigenous Australians, vital to promote equity and remedy problems that exist within Aboriginal communities, continue to be overlooked. Current political processes make it difficult for Indigenous people to have power over decisions made on their behalf to solve issues prevalent in Aboriginal communities. This is largely as “Aboriginal representatives are in a better position to represent Aboriginal people and that existing politicians do not or cannot perform this role.” Deeply “entrenched inequality in Australia” has led to the continuity of traditional Anglo- Australian Parliamentary values, which inherently exclude Indigenous Australians. Additionally, the communication between the White Australian population and the Aboriginal population remains damaged, due to “European contact tend[ing] to undermine Aboriginal laws, society, culture and religion”. -

Trees for Farm Forestry: 22 Promising Species

Forestry and Forest Products Natural Heritage Trust Helping Communities Helping Australia TREES FOR FARM FORESTRY: 22 PROMISING SPECIES Forestry and Forest Products TREES FOR FARM FORESTRY: Natural Heritage 22 PROMISING SPECIES Trust Helping Communities Helping Australia A report for the RIRDC/ Land & Water Australia/ FWPRDC Joint Venture Agroforestry Program Revised and Edited by Bronwyn Clarke, Ian McLeod and Tim Vercoe March 2009 i © 2008 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 1 74151 821 0 ISSN 1440-6845 Trees for Farm Forestry: 22 promising species Publication No. 09/015 Project No. CSF-56A The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

To Download the Official Mail-In Rebate Form, Visit Pgmovienights.Com

Receive 1 adult and 1 child movie certificate to Disney·Pixar’s FINDING DORY by email or mail when you purchase $30 of P&G products in one (1) transaction from ShurSave or Family Owned Markets. Qualifying purchases must be made 5/6/16 through 6/30/16 To download the official mail-in rebate form, visit pgmovienights.com TERMS AND CONDITIONS: When you successfully redeem this offer as specified below, you will receive two reward codes redeemable for one (1) adult and (1) child movie certificate to see Disney • Pixar’s Finding Dory. P&G reserves the right to substitute the item offered with a new item of equal or greater value if it becomes unavailable for any reason. Mail in offer forms from a non-participating store will not be honored. To redeem this offer at any participating ShurSave or Family Owned Markets, purchase $30 of participating Procter & Gamble products: Aussie®, Bounce®, Bounty®, Camay®, Cascade®, Cheer®, Crest®, Dawn®, Downy®, Era®, Febreze®, Gain®, See store for official mail-in form. Gleem®, Glide®, Head & Shoulders®, Herbal Essences®, Ivory®, Joy®, Mr. Clean®, Olay®, Oral B®, Pantene®, Safeguard®, Scope®, Swiffer®, Tide®, Vidal Sassoon®. Non-participating products include: Braun®, Downy® Unstopables by Febreze, Gain® Flings, Tide® Pods, Vicks®, SHAVE CARE CATEGORY. Not valid for any Prilosec OTC product reimbursed or paid under Medicaid, Medicare, or any federal or state healthcare program, including state medical and pharmacy assistance programs, or where prohibited by law. Not valid in Massachusetts if any part of the product cost is reimbursed by public or private health insurance. Sales tax is not included towards $30 in purchased products. -

A Diachronic Study of Unparliamentary Language in the New Zealand Parliament, 1890-1950

WITHDRAW AND APOLOGISE: A DIACHRONIC STUDY OF UNPARLIAMENTARY LANGUAGE IN THE NEW ZEALAND PARLIAMENT, 1890-1950 BY RUTH GRAHAM A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Linguistics Victoria University of Wellington 2016 ii “Parliament, after all, is not a Sunday school; it is a talking-shop; a place of debate”. (Barnard, 1943) iii Abstract This study presents a diachronic analysis of the language ruled to be unparliamentary in the New Zealand Parliament from 1890 to 1950. While unparliamentary language is sometimes referred to as ‘parliamentary insults’ (Ilie, 2001), this study has a wider definition: the language used in a legislative chamber is unparliamentary when it is ruled or signalled by the Speaker as out of order or likely to cause disorder. The user is required to articulate a statement of withdrawal and apology or risk further censure. The analysis uses the Communities of Practice theoretical framework, developed by Wenger (1998) and enhanced with linguistic impoliteness, as defined by Mills (2005) in order to contextualise the use of unparliamentary language within a highly regulated institutional setting. The study identifies and categorises the lexis of unparliamentary language, including a focus on examples that use New Zealand English or te reo Māori. Approximately 2600 examples of unparliamentary language, along with bibliographic, lexical, descriptive and contextual information, were entered into a custom designed relational database. The examples were categorised into three: ‘core concepts’, ‘personal reflections’ and the ‘political environment’, with a number of sub-categories. This revealed a previously unknown category of ‘situation dependent’ unparliamentary language and a creative use of ‘animal reflections’. -

South Australian State Public Sector Organisations

South Australian state public sector organisations The entities listed below are controlled by the government. The sectors to which these entities belong are based on the date of the release of the 2016–17 State Budget. The government’s interest in each of the public non-financial corporations and public financial corporations listed below is 100 per cent. Public Public General Non-Financial Financial Government Corporations Corporations Sector Sector Sector Adelaide Cemeteries Authority * Adelaide Festival Centre Trust * Adelaide Festival Corporation * Adelaide Film Festival * Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources * Management Board Adelaide Venue Management Corporation * Alinytjara Wilurara Natural Resources Management Board * Art Gallery Board, The * Attorney-General’s Department * Auditor-General’s Department * Australian Children’s Performing Arts Company * (trading as Windmill Performing Arts) Bio Innovation SA * Botanic Gardens State Herbarium, Board of * Carrick Hill Trust * Coast Protection Board * Communities and Social Inclusion, Department for * Correctional Services, Department for * Courts Administration Authority * CTP Regulator * Dairy Authority of South Australia * Defence SA * Distribution Lessor Corporation * Dog and Cat Management Board * Dog Fence Board * Education Adelaide * Education and Child Development, Department for * Electoral Commission of South Australia * Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Department of * Environment Protection Authority * Essential Services Commission of South Australia -

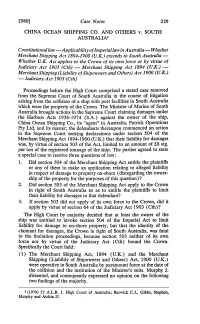

Imagereal Capture

1980] Case Notes 229 CHINA OCEAN SHIPPING CO. AND OTHERS v. SOUTH AUSTRALIAl Constitutionallaw-ApplicabilityofImperial law in Australia-Whether Merchant Shipping Act 1894-1900 (U.K.) extends to South Australia Whether U.K. Act applies to the Crown of its own force or by virtue of Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) - Merchant Shipping Act 1894 (U.K.) Merchant Shipping (Liability 0/ Shipowners and Others) Act 1900 (U.K.) -Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) Proceedings before the High Court comprised a stated case removed from the Supreme Court of South Australia in the course of litigation arising from the collision of a ship with port facilities in South Australia which were the property of the Crown. The Minister of Marine of South Australia brought actions in the Supreme Court claiming damages under the Harbors Acts 1936-1974 (S.A.) against the owner of the ship, China Ocean Shipping Co., its "agent" in Australia, Patrick Operations Pty Ltd, and its master; the defendants thereupon commenced an action in the Supreme Court seeking declarations under section 504 of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894-1900 (U.K.) that their liability for damages was, by virtue of section 503 of the Act, limited to an amount of £8 stg. per ton of the registered tonnage of the ship. The parties agreed to state a special case to resolve three questions of law: 1. Did section 504 of the Merchant Shipping Act entitle the plaintiffs or any of them to make an application relating to alleged liability in respect of damage to property on-shore (disregarding the owner ship of the property for the purposes of this question)? 2. -

Australian Nationalism and Historical Memory

UCLA UCLA Historical Journal Title An Ambivalent Nation: Australian Nationalism and Historical Memory Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4dd790wr Journal UCLA Historical Journal, 23(1) ISSN 0276-864X Author Kelly, Matthew Kraig Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California An Ambivalent Nation: Australian Nationalism and Historical Memory Matthew Kelly The most important national holiday in Australia falls on April 25. Known as Anzac Day, it commemorates the Australian and New Zealander soldiers who died in battle at Gallipoli, in western Turkey, in 1915.1 Gallipoli’s central position in Australian national consciousness is not immediately comprehensible to an outside observer. Bastille Day in France or Independence Day in the United States seem sensible choices for the national holiday. In the French case, the storming of the Bastille is a suitable emblem of the transi- tion from the ancien régime to a new political order in which all Frenchmen were to be equals before the law. In the American case, the celebration of independence summons the specter of a national consciousness shaking off the last fetters of British imperial rule and so coming to full bloom. But why should a battlefield located thou- sands of miles from Australia, and from which Australians derived no material benefit, serve, in an important respect, as the geographic center of the Australian national narrative? Which overlords did the Australians overturn at Gallipoli? From whose imperial yoke did they at last work loose? The last two questions are rhetorical, of course, for neither applies to the Australian case. -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017).