Sheriffdom of Lothian and Borders at Edinburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake District Classic Rally

Steven & David Byrne : Lake District Classic Rally : Photo - Chris Ellison Chairmans Chat Contents It must be summer because instead of power washing mud off Front Cover : Lake District Classic Rally the car after marshalling on a stage rally I spent an hour vac- Pg. 2 Chairman's Chat uuming dust out of the car after the Greystoke Stages ! Being Pg. 3 Member Club Contacts at the start and later the stop line the dust wasn't too bad until the crew of a low numbered car managed to totally ignore the Pg. 4 More SD34MSG Contacts 3, 2, 1 and stop boards and pass at high speed and covering Pg. 5 Around the Clubs (1) every one and thing in a liberal covering !! Pg. 6 Around the Clubs (2) I would like to welcome Lancashire Automobile Club back to SD34 MSG after they recently rejoined and you can read an Pg. 7 2013 SD34MSG Calendar article about the club on page 13. In anticipation of the club Pg. 8 2013 Championship Rounds at a glance rejoining we had invited their co-promoted 3 Sisters Sprint on Pg. 9 SD34MSG Championship Registration 4th August to our championship but in future the event will automatically be included. Apart from the sprint the club is pri- Pg. 10 2013 SD34 MSG Championship Tables marily involved in historic events so this aspect of our sport will Pg. 11 2013 SD34 MSG Marshals Championship give an interesting addition to our members. Pg. 12 2013 SD34 MSG Inter-Club League SD34 MSG Meeting Highlights Pg. 13 Welcome Back - Lancashire A.C Meeting 17th July 2013 David Bell of Lancashire Automobile Club gave a summary of Pg. -

Colin Mcrae Forest Stages 2007 Final Official Classification Award Winners

COLIN MCRAE FOREST STAGES 2007 FINAL OFFICIAL CLASSIFICATION AWARD WINNERS DRIVER POS NO. CO-DRIVER VEHICLE CLASS OVERALL CLASSIFICATION AWARDS 1 104 DAVID BOGIE TOYOTA COROLLA WRC 10 DAVID PATERSON 2 105 NEALE DOUGAN SUBARU IMPREZA WRC 9 RORY DOYLE 3 103 JIMMY GIRVAN SUBARU IMPREZA 10 MIKE RAMSAY AWARD - CLASS 10 - ALL OTHER 4WD CARS OVER 2000CC 1 113 DAVID HUGHES MITSUBISHI STEP 2 WRC 10 LOUISE SUTHERLAND 2 126 WILLIAM JARMAN FORD ESCORT COSWORTH 10 MARK FISHER AWARD - CLASS 9 - GROUP A 4WD CARS OVER 2000CC 1 107 JIM CARTY SUBARU IMPREZA WRC 9 NEIL SHANKS 2 119 STEVEN CAMPBELL MITSUBISHI LANCER EVO 5 9 SUSAN BROWN AWARD - CLASS 8 - GROUP N 4WD CARS OVER 2000CC 1 108 STEVEN CLARK MITSUBISHI LANCER EVO 4 8 LEE KERR 2 121 EUAN THORBURN SUBARU IMPREZA 8 SIMON MILLS AWARD - CLASS 7 - 2WD CARS OVER 2000CC 1 92 SEAMUS O'CONNELL FORD ESCORT MK2 7 SEAN MAGEE 2 11 JOHN PATERSON FORD ESCORT MK2 7 WILLIAM SMILLIE AWARD - CLASS 6 - 2WD CARS WITH 16 VALVES TO 2000CC 1 3 CALUM MACKENZIE FORD ESCORT 6 ALAN CLARK 24KEITH ROBATHAN FORD ESCORT MK2 6 NEIL EWING AWARD - CLASS 5 - 2WD CARS WITH 8 VALVES TO 2000CC 143IAN MUNRO PEUGEOT 205 GTI 5 NEIL THOMSON 2 59 JOHN LAWSON FORD ESCORT 5 ALAN MAXWELL AWARD - CLASS 4 - 2WD CARS WITH 16 VALVES UP TO 1600CC 149NEIL COALTER HONDA CIVIC 4 HANNAH CESSFORD 2 52 DES CAMPBELL PEUGEOT 206 4 JAMES BRAITHWAITE AWARD - CLASS 3 - 2WD CARS WITH 8 VALVES UP TO 1600CC 128IAN RAE TALBOT SUNBEAM 3 DAVID FINDLAY 2 40 HAROLD MCALLISTER TALBOT SUNBEAM 3 ALEX EWART AWARD - CLASS 2 - 2WD CARS WITH 16 VALVES TO 1400CC 1 NO FINISHER ELIGIBLE 2 NO FINISHER ELIGIBLE AWARD - CLASS 1 - 2WD CARS WITH 8 VALVES TO 1400CC 168CHARLIE MUNRO FORD ESCORT MK2 1 MICHAEL BAIRD 2 70 DAVID MACLEAN PEUGEOT 106 RALLYE 1 LYNDA MACLEAN AWARD - CLASS 11 - HISTORIC CARS 1 60 DAVID KILLIN OPEL KADETT 11 GRAEME TAYLOR 2 NO FINISHER ELIGIBLE AWARD - 1ST FORD CAR 1 3 CALUM MACKENZIE FORD ESCORT 6 ALAN CLARK RESULTS BY RMS - [email protected] (© COPYRIGHT RMS 2007) (11:00) COLIN MCRAE FOREST STAGES 2007 FINAL OFFICIAL CLASSIFICATION AWARD WINNERS DRIVER POS NO. -

1968 − 1984 Colin: the Busy Baby by Margaret Mcrae

1968 − 1984 Colin: the busy baby by Margaret McRae Colin Steele McRae was born on August 5, 1968. It was a Monday. He was born in the William Smellie Maternity Hospital in Lanark. And he was a much-wanted child – a first grandchild for my parents, however Jim’s mum and dad already had two. It’s from Jim’s mum that Colin took the name Steele – it was her maiden name. We were living in Blackwood, about five miles from Lanark, in those days. And it was to the house in Vere Road, Blackwood that we would have taken Colin home – if we hadn’t still been renovating the cottage at the time. Instead, we went and stayed with my parents for two or three weeks while we finished the work on the house. This was actually quite a God-send as my dad wasn’t feeling too well at the time and having a newborn baby in the house really took his mind off things. He spent all of his time, just focused on the baby. Right from the off, Colin was a busy baby and, unfortunately for us, not a baby to whom sleep came easily or quickly. I think he stayed in our room for about seven weeks, before we knew the time had come for him to go into his own room. I don’t think Colin really slept through the night completely for about two years. Alister, his younger brother, was something of a revelation by comparison and slept really quickly. It’s fair to say, Colin wasn’t an easy baby. -

A Sensational Season Full of Celebrations

Motorsport News UK UK Edition - End of season 2018 A sensational season full of celebrations... Image Tag Image Tag Motorsport News UK UK Edition - November 2018 Final ‘Stats’... FUCHS & FUCHS Silkolene have enjoyed lots of success in 2018 with champions across the board. See where everyone finished in our tables below. 2 Wheel Motorsport 4 Wheel Motorsport Championship Team / Rider Position Championship Team / Driver Position BSB JG Speedfit Kawasaki BTCC Ciceley Motorsport Leon Haslam 1st Adam Morgan 7th Luke Mossey 15th Tom Oliphant 22nd Be Wiser Ducati (PBM) FUCHS LUBRICANTS Paul Barrett 1st Glenn Irwin 3rd MSA BHRC Shane Byrne 16th Andrew Irwin 17th FUCHS LUBRICANTS Simon Tysoe 1st Smiths Racing RAC RMC Peter Hickman 5th Sylvain Barrier 21st MSA Supernational Bellerby Motorsport 4th FS-3 Racing Rallycross Paige Bellerby Danny Buchan 11th Championship Halsall Racing BMW Mini Bellerby Motorsport 4th Chrissy Rouse 22nd Rallycross Drew Bellerby Championship National 1000cc EHA Racing Superstock Joe Collier 3rd BRC CA1 Sport Andy Reid 8th David Bogie 3rd FS-3 Racing Lee Jackson 6th National Hot Rod M&M Motorsport Halsall Racing Gavin Murray 4th* Tom Ward 15th Scottish Mini Ashleigh Morris 10th British Supersport EHA Racing Cooper Cup Championship David Allingham 6th Alistair Seeley 9th Scottish Mini Ashleigh Morris 1st Ross Twyman 11th Cooper Cup - Ladies CF Motorsport BARC Modified Holden Racing UK Kyle Ryde 21st Saloons Alex Sidwell 5th British Junior Team 109 Racing Supersport Eunan McGlinchey 1st Civic Cup Sharp Motorsport Arron Sharp -

Chairmans Chat Front Cover - Member Clubs Since the Last Issue of „Spotlight‟ – the SD34 MSG Monthly Mo- Pg

Contents Chairmans Chat Front Cover - Member Clubs Since the last issue of „spotlight‟ – The SD34 MSG Monthly Mo- Pg. 2 Chairmans Chat torsport Magazine – I spent two days helping on the Wales Rally Pg. 3 Member Club Contacts GB in North and Mid Wales and thankfully the weather on Days 1 Pg. 4 More SD34MSG Contacts and 3 was lovely although I believe Day 2 was very wet. What I Pg. 5 Around the Clubs (1) want to know is “Why does it take so many more people, in their Pg. 6 Around the Clubs (2) numerous vehicles, to run this event than it does to run all the Pg. 7 Rally of the Incas other events we all help on during the year ???” Pg. 8 SD34 MSG League Positions I am pleased to welcome Fylde Motor Sport Club who will be Pg. 9 SD34 MSG Championship Tables joining the Group from 1st January 2012. This is a local club newly Pg. 10 Wales Rally GB - WRC recognised by the MSA but some of the members have been in- Pg. 11 More Wales Rally GB volved in motorsport for many years but more importantly the club Pg. 12 WRC Academy Champion has got several keen young members which are vital to the future Pg. 13 Roger Albert Clark Rally of our beloved sport. There is a healthy enthusiasm to get involved Pg. 14 Tempest Rally in events so I‟m sure our existing member clubs will welcome any Pg. 15 Odds Sods & Bodkins extra hands offered in running events and in that way FMSC can Pg. -

RSAC Scottish Rally Aim to Offer Competitors and Spectators a Challenging Event Over Some of the Best Stages in Scotland

FOREWORD Once again, the organisers of the RSAC Scottish Rally aim to offer competitors and spectators a challenging event over some of the best stages in Scotland. We have built on the best of previous years’ events as well as introducing some new features this year. We listened to last year’s feedback from competitors and have deleted some of the less popular stage mileage from the route. This year’s rally offers: • A compact route with plenty of service opportunities. • A competitive entry fee. • Rally HQ, scrutineering and service park at Lockerbie Lorry Park, within easy reach of all parts of the UK as it is only a short distance from the motorway system. • National A ceremonial start in the centre of Dumfries, and finish in the centre of Moffat. • Prizegivings on the finish ramp. • Two Media Stages before the event, which will also allow testing opportunities, run by John Parker Associates. We are pleased to be a round of the MSA British Rally Championship, and we welcome the new sponsors Prestone and competitors from all over the world. We are proud to mark the halfway point of the ARR Craib MSA Scottish Rally Championship, and we also welcome competitors in the RSAC Motorsport Ecosse Challenge and the Border Challenge. We are also pleased to welcome our friends from the British Army Motorsports Association, whose Land Rovers have been part of the event since 1963. This year we are pleased to support the Children’s Hospice Association Scotland (CHAS). We hope you will be generous in your support of this very worthwhile cause. -

RSAC Scottish Rally Aim to Offer Competitors and Spectators a Challenging Event Over Some of the Best Stages in Scotland

RGS 01.16 FOREWORD Once again, the organisers of the RSAC Scottish Rally aim to offer competitors and spectators a challenging event over some of the best stages in Scotland. We have built on the best of previous years’ events as well as introducing some new features this year, and we can offer you: • The chance for Scottish and British Rally Championship competitors to compete in the same event over the same route. • Nearly ten miles of stages never rallied before. • A competitive entry fee. • Rally HQ and scrutineering at Scotland’s Rural College Barony Campus. • A ceremonial start and finish in the centre of Dumfries. • Central servicing at Heathhall. • Prize-giving on the finish ramp. • Participation in the Open Day at SRUC Barony Campus before the event. • A Media Stage before the event, which will also allow testing opportunities, run by John Parker Associates. We are pleased to be a round of the MSA British Rally Championship, and we welcome competitors from all over the world who are contributing to the revival of this famous series. We are proud to mark the beginning of the second half of the ARR Craib MSA Scottish Rally Championship, and we also welcome competitors in both classes of the C2 MotorSports.com Ecosse Challenge, the Border Challenge, the Motoscope Northern Historic Rally Championship and the Five of Clubs Rally Championship. We are also pleased to welcome our friends from the British Army Motorsports Association, whose Land Rovers have been part of the event since 1963. Following our successful collaboration last year, we will again be supporting The Usual Place, a community café in Dumfries which works with young people (aged 16-26) who have a wide range of physical and mental health problems. -

John Surtees CBE, 1934-2017 Pages 2-3

MSA EXTRA THE NEWSLETTER FOR BRITISH MOTOR SPORT MARCH 2017 John Surtees CBE, 1934-2017 Pages 2-3 4 5 20 NEWS NEWS NEWS BMSAD Chairman’s MSA supports FIA Marshall named MSA Lifetime campaign as Paddon’s new Achievement Award with JCDecaux co-driver @msauk /msauk msa_motorsport www.msauk.org Cover JOHN SURTEES CBE, 1934-2017 “John’s passing is an enormous The MSA has paid tribute to motorsport legend loss to motorsport John Surtees CBE, who passed away last Friday in so many ways; (10 March) aged 83. the legend, the John made history as the only man to win world championships on four wheels and two, with four 500cc motorcycle triumphs in the 1950s and ’60s, followed by the 1964 F1 history, the title. In recent years he established the Henry Surtees Foundation in memory of his late heritage, the son, Henry. He also bought Buckmore Park Kart Circuit in Kent and remained a stalwart passion and the support of UK motorsport throughout his life. Rob Jones, MSA Chief Executive, said: “John’s passing is an enormous loss to motorsport commitment, not in so many ways; the legend, the history, the heritage, the passion and the commitment, to mention the not to mention the success, which will not be surpassed. success, which will “I recently spent some time with John at his home, where despite his frailty he was as enthusiastic as ever to talk about further plans for Buckmore Park, the development of not be surpassed karting generally and of course his beloved Henry Surtees Foundation. -

2002 Regulations

2018 REGULATIONS 1. GENERAL 1.1 SRC Car Club Ltd will promote the 2018 ARR Craib MSA Scottish Rally Championship, incorporating the Scottish 2 Wheel Drive Championship and the SRC Challengers Championship. 1.2 The Championship is held under the General Regulations of the Motor Sports Association (incorporating the provisions of the International Sporting Code of the FIA) and these Championship Regulations. The Championship Permit No. is 2018/010. 1.3 The Championship is open to fully elected members of Clubs which are members of the following associations: • Scottish Association of Car Clubs • Association of Northern Ireland Car Clubs • Association of North East & Cumbria Car Clubs • Association of Northern Car Clubs 1.4 The Championship Management Committee, elected by the clubs organising rounds of the 2018 SRC, and in accordance with the General Regulations of the MSA, reserves the right to: a. Issue additional regulations b. Amend present regulations c. Announce additional awards d. Rule on matters of eligibility 1.5 As required by the MSA, a panel of Stewards has been appointed. They are:- • Robert Harkness • Brian Kinghorn • Iain Edwards 1.6 All protests, in respect of these Regulations, must be lodged in accordance with the General Regulations of the MSA. 1.7 The Championship Updates and/or Championship Bulletins issued by the championship co- ordinator will be the official medium for confirming changes to, or additions to, the Championship Regulations, including the announcement of any additional awards. Registered competitors shall receive Championship Updates/Bulletins/Points Tables via e-mail or online via the championship website. MSA Scottish Rally Championship 2018 Regulations Page 1 1.8 Registration in the ARR CRAIB MSA Scottish Rally Championship does not guarantee entry in the events which count towards the Championship. -

RMS - [email protected] (© COPYRIGHT RMS 2008) (18:49) MCDONALD & MUNRO SPEYSIDE STAGES 2017 FINAL OFFICIAL CLASSIFICATION AWARD WINNERS

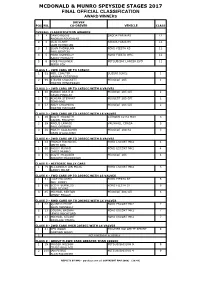

MCDONALD & MUNRO SPEYSIDE STAGES 2017 FINAL OFFICIAL CLASSIFICATION AWARD WINNERS DRIVER POS NO. CO-DRIVER VEHICLE CLASS OVERALL CLASSIFICATION AWARDS 1 1 DAVID BOGIE SKODA FABIA R5 12 ANDREW ROUGHEAD 24DESI HENRY SKODA FABIA R5 12 LIAM MOYNIHAN 33EUAN THORBURN FORD FIESTA R5 12 PAUL BEATON 4 5 MARK DONNELLY FORD FIESTA WRC 12 BARRY MCNULTY 5 6 MIKE FAULKNER MITSUBISHI LANCER EVO 11 PETER FOY CLASS 1 - 2WD CARS UP TO 1450CC 152NEIL COALTER SUZUKI IGNIS 1 HANNAH CESSFORD 2 99 STEVEN CROCKETT PEUGEOT 205 1 MARTIN HENDERSON CLASS 2 - 2WD CARS UP TO 1650CC WITH 8 VALVES 1 60 ROBBIE BEATTIE PEUGEOT 205 GTI 2 DAVID FINDLAY 2 72 ADRIAN STEWART PEUGEOT 205 GTI 2 TOM HYND 3 57 ANDY CHALMERS PEUGEOT 205 GTI 2 MARTIN MACCABE CLASS 3 - 2WD CARS UP TO 1650CC WITH 16 VALVES 1 38 SCOTT MACBETH CITROEN C2 R2 MAX 3 DANIEL FORSYTH 239ANGUS LAWRIE VAUXHALL CORSA 3 PAUL GRIBBEN 3 36 MARTY GALLAGHER PEUGEOT 208 R2 3 DEAN O'SULLIVAN CLASS 4 - 2WD CARS UP TO 2050CC WITH 8 VALVES 1 34 FRASER MACNICOL FORD ESCORT MK2 4 KEITH BOA 2 66 PADDY MUNRO FORD ESCORT MK2 4 CHRIS MUNRO 3 75 SCOTT MCQUEEN PEUGEOT 205 4 ANDREW MACKINNON CLASS 5 - HISTORIC RALLY CARS 1 79 ALEXANDER IAN MILNE FORD ESCORT MK2 5 SANDY MILNE CLASS 6 - FWD CARS UP TO 2050CC WITH 16 VALVES 1 61 LUKE MCLAREN FORD FIESTA ST 6 PHIL KENNY 2 68 SCOTT BURNESS FORD FIESTA ST 6 JODI DEVINE 385MICHAEL RENTON PEUGEOT 306 GTI 6 KENNY FOGGO CLASS 7 - RWD CARS UP TO 2050CC WITH 16 VALVES 122QUINTIN MILNE FORD ESCORT MK2 7 SEAN DONNELLY 2 23 DOUGAL BROWN FORD ESCORT MK2 7 LEWIS ROCHFORD 347MICHAEL STUART FORD ESCORT MK2 7 SINCLAIR YOUNG CLASS 8 - 2WD CARS OVER 2050CC WITH 16 VALVES 1 41 KEN WOOD TRIUMPH DOLOMITE SPRINT 8 GORDON WOOD 2 NO FINISHER ELIGIBLE CLASS 9 - GROUP N 4WD CARS GREATER THAN 2000CC 1 19 FRASER WILSON MITSUBISHI EVO 9 9 CRAIG WALLACE 2 105 IAN PETRIE MITSUBISHI EVO 4 9 ALAN FALCONER RESULTS BY RMS - [email protected] (© COPYRIGHT RMS 2008) (18:49) MCDONALD & MUNRO SPEYSIDE STAGES 2017 FINAL OFFICIAL CLASSIFICATION AWARD WINNERS DRIVER POS NO. -

MSA Pays Tribute to British GP Volunteers Page 2-3

MSA EXTRA THE NEWSLETTER FOR BRITISH MOTOR SPORT JULY 2018 MSA pays tribute to British GP volunteers Page 2-3 4 8 11 NEWS NEWS VACANCIES Grayling and Todt Opportunities Head of Education & discuss Vnuk at for new MSA Training and Safety Silverstone Registrars Administrator @msauk /msauk msa_motorsport www.msauk.org Cover MSA PAYS TRIBUTE TO BRITISH GP VOLUNTEERS MSA Chairman David Richards has paid tribute to the British Grand Prix marshals in an open letter praising their contribution to a “near-perfect weekend”. 2 MSA Extra / July 2018 Cover Richards wrote: “After a record race- “This year Silverstone offered one day crowd and a heroic drive by Lewis volunteer a ride in the two-seater F1 Hamilton, it’s difficult to pick a highlight car and we’re delighted that one of our of the British Grand Prix. However, one of marshals, Stuart Glanfield, was the lucky mine was certainly visiting the marshals’ passenger. As usual the MSA will also be campsite to meet some of the men and running a random prize draw among the women who helped make it all happen. marshals for a chance to win grandstand tickets to next year’s race and passes to “There were nearly 1000 volunteers at Dayinsure Wales Rally GB.” Silverstone and their dedication was evident throughout the weekend, as The MSA offers its sincere thanks to all they kept everything running smoothly those who made the 2018 British Grand through the extraordinary heat. Whether Prix such a wonderful occasion for both marshals, recovery crews, scrutineers, UK and world motorsport. -

Mag Final 02 2021 Feb

STAGE TIMES The Magazine of North Humberside Motor Club Ltd CLUB DIRECTORS*, OFFICIALS & COMMITTEE President Membership Secretary Ian Sadofsky* (01482-635202) Dennis Robinson* (01482-651069) [email protected] [email protected] Chairman Treasurer David James* (01262-606420) Ian James* (07713-573432) [email protected] [email protected] Vice President Competition Secretary Dave Cogan (01482-631963) Robert Newlove* (01377-270888) [email protected] [email protected] Vice President, Vice Magazine Editor Chairman & Chief Marshal Gavin Heseltine* (01430-440114) John Newlove* (01904-608524) [email protected] [email protected] Secretary Safeguarding Officer Gail Newlove (01377-270888) Chris Newlove* (07729-721937) [email protected] [email protected] OTHER DIRECTORS* & COMMITTEE Tom Hutchings* (07975-714159) Kirsty Thompson (07725-950344) [email protected] [email protected] Carl Thompson * (01759-306671) Steve Varey* (01482-876641) [email protected] [email protected] DIRECTORS INDICATED WITH AN ASTERISK (*) AFTER THEIR NAME Future Board Meetings (Start At 8pm) Please do not telephone Directors, Wed 24th Mar (Zoom Call) Officials or Committee Members Wed 28th Apr (Zoom Call) after 10pm Wed 26th May (Zoom Call) facebook.com/northhumbersidemc www.nhmcwarcopstages.co.uk Editors Ramblings … Inside this issue Welcome to “STAGE TIMES”. Officials & Committee Members IFC Editors Ramblings 1 Apologise for the missing December/ January Magazine and the late arrival of Forthcoming Events 2/3 this one (was due beginning of February) but with no Motorsport taking place I had News and Bits & Pieces 4 lost all motivation. NHMC Warcop Rally 2021 5 I assume you have all been affected by New deal for forest rallying 6/7 the same thing as, apart from Ian North, no one has submitted any articles.