Boston's New Urban Ring: an Antidote to Urban Fragmentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail/Restaurant Opportunity Dudley Square

RETAIL/RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITY 2262 WASHINGTON STREET DUDLEY ROXBURY, MASSACHUSETTS SQUARE CRITICALDates NEIGHBORHOODOverview MONDAY • DECEMBER 9, 2013 Distribution of Request for Proposals (RFP) • Located at the junction of Washington and Warren Streets with convenient access to Interstates 93 and 90 (Massachusetts Bid Counter • 26 Court Street, 10th floor Turnpike) Boston, MA • Dudley Square has a population of approximately 80,000 people and 28,000 households within a one mile radius • Retail demand and spending by neighborhood residents is upwards of $610 million annually TUESDAY • JANUARY 14, 2014 • Approximately $300 million in public/private dollars have been invested in the neighborhood since 2000 Proposer Conference • 2:00 P.M. Central Boston Elder Services Buliding • Dudley Square is within a mile of Boston’s Financial District, blocks away from the South End and is within walking distance to 2315 Washington Street Northeastern University, Roxbury Community College, Boston Medical Center and BU Medical School and in proximity to Mission Hill and WARREN STREET Roxbury, MA Jamaica Plain • Dudley Square Station is located adjacent to the site and provides local bus service that connects Dudley to the MBTA’s Ruggles Station MONDAY • FEBRUARY 10, 2014 Orange Line stop and Silver Line service to Downtown Boston. Dudley Square Station is the region’s busiest bus station and Completed RFP’s due by 2:00 P.M. averages 30,000 passengers daily SEAPORT BOULEVARD BACK BAY SUMMER STREET Bid Counter • 26 Court Street, 10th floor COMMONWEALTH -

Roxbury-Dorchester-Mattapan Transit Needs Study

Roxbury-Dorchester-Mattapan Transit Needs Study SEPTEMBER 2012 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. This report was funded in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration [and Federal Transit Administration], U.S. Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the authors [or agency] expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U. S. Department of Transportation. i Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 A Lack of Trust .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 The Loss of Rapid Transit Service ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Directions to 140 the FENWAY, NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Walking Directions to 140 the Fenway • from Longwood: Walk Towards the Museum of Fine Arts

Directions to 140 THE FENWAY, NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Walking Directions to 140 The Fenway • From Longwood: walk towards the Museum of Fine Arts. Walk to the east side (closest to the Prudential Tower) of the MFA. 140 Fenway is the large marble building facing the Fens. Enter through the door facing the small parking lot. • From the Back Bay/Prudential area: Walk down Huntington Avenue towards Symphony Hall. Cross Massachusetts Avenue, continue on Huntington Ave to Forsyth Street. There is a Qdoba on the corner. Turn right on Forsyth and walk one block to Hemenway Street (140 Fenway is the building directly in front of you). Turn left. Make a right into the parking lot and the entrance to the building will be on your right. Driving directions to the Renaissance Park Garage, 835 Columbus Avenue, Boston, MA 02120 • From the north (via Route I-93 or Route 1) Take the Storrow Drive exit, and proceed to the Fenway exit. Follow signs for Boylston Street inbound, and bear right onto Westland Avenue. Turn right onto Massachusetts Avenue, proceed to the third traffic light, and turn right onto Columbus Avenue. The Renaissance Parking Garage is at 835 Columbus Avenue. • From the west (via Route I-90, Massachusetts Turnpike) Take Exit 22 (Copley Square), and bear right. Proceed to the first traffic light, and turn right onto Dartmouth Street. Take the next right onto Columbus Avenue. The Renaissance Parking Garage is at 835 Columbus Avenue. • From the west (via Route 9) Proceed east on Route 9; it will become Huntington Avenue. Turn right onto Ruggles Street. -

Institutional Master Plan 2021-2031 Boston Medical Center

Institutional Master Plan 2021-2031 Boston Medical Center May 3, 2021 SUBMITTED TO: Boston Planning and Development Agency One City Hall Square Boston, MA 02201 Submitted pursuant to Article 80D of the Boston Zoning Code SUBMITTED BY: Boston Medical Center Corporation One Boston Medical Center Place Boston, MA 02118 PREPARED BY: Stantec 226 Causeway Street, 6th Floor Boston, MA 02114 617.654.6057 IN ASSOCIATION WITH: Tsoi-Kobus Design VHB DLA Piper Contents 1.0 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 INSTITUTIONAL MASTER PLAN HISTORY ............................................................... 1-1 1.3 PROGRESS ON APPROVED 2010-2020 IMP PROJECTS ........................................ 1-2 1.4 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES FOR THE 2021-2031 IMP ............................................... 1-3 1.5 A MEASURED APPROACH TO CAMPUS GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY ........... 1-4 1.6 PUBLIC REVIEW PROCESS ...................................................................................... 1-5 1.7 SUMMARY OF IMP PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY BENEFITS ...................................... 1-6 1.8 PROJECT TEAM ......................................................................................................... 1-9 2.0 MISSION AND OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 OBJECTIVES -

Massdep Legionella Information

MassDEP Drinking Water Program th One Winter Street – 5 Floor; Boston, MA 02108 [email protected] or 617-292-5770 Drinking Water Program Updates 2019-12-20 This week’s program director email has these topics of interest: 1. Legionella Information 2. Update on the Proposed LCR Revisions 3. LCR 90th Percentile Data Reports 4. Submission Extension: Mercury-Containing Equipment Survey 5. Recruit and Retain Operators 6. Snow Disposal in Zone II and Zone A 7. Critical Infrastructure Security End of Year Update 8. Annual Nonpoint Source Pollution Conference 9. PFAS Training Video 10. Training Calendar Legionella Information To raise your awareness of Legionella and changes in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health care facilities requirements that may impact CMS and VHA facilities on your distribution system and your water system. The following information is attached: • Legionella information letter • Legionella FAQ and Resources • List of Health care facilities in Massachusetts This information is also available on our webpage: https://www.mass.gov/lists/drinking-water- contaminants-information-for-water-suppliers Update on the Proposed LCR Revisions On November 13, 2019, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published in the Federal Register a proposed rule pertaining to the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) for lead and copper under the authority of the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) and requested comments by January 13, 2020. In response to stakeholder requests, the EPA is extending the comment period an additional 30 days to February 12, 2020. -

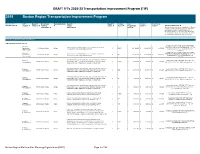

2017-2021 Tip Template

DRAFT FFYs 2019-23 Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) 2019 Boston Region Transportation Improvement Program Amendment / STIP MassDOT Metropolitan Municipality Name MassDOT MassDOT Funding Total Federal Non-Federal Adjustment Type ▼ Program ▼ Project ID ▼ Planning ▼ Project District ▼ Source ▼ Programmed Funds ▼ Funds ▼ Additional Information ▼ Organization ▼ Description▼ Funds ▼ Present information as follows, if applicable: a) Planning / Design / or Construction; b) total project cost and funding sources used; c) advance construction status; d) MPO project score; e) name of entity receiving a transfer; f) name of entity paying the non-state non-federal match; g) earmark details; h) TAP project proponent; i) other information ►Section 1A / Regionally Prioritized Projects ►Regionally Prioritized Projects Construction; STP+CMAQ+Section 5309 (Transit) Planning / GREEN LINE EXTENSION PROJECT- EXTENSION TO COLLEGE Total MPO Contribution = $190,000,000; AC Yr 4 of 6; Adjustments / 1570 Boston Region Multiple 6 CMAQ $ 28,184,400 $ 22,547,520 $ 5,636,880 AVENUE WITH THE UNION SQUARE SPUR funding flexed to FTA; match provided by local Pass-throughs contributions Construction; STP+CMAQ+Section 5309 (Transit) Planning / GREEN LINE EXTENSION PROJECT- EXTENSION TO COLLEGE Total MPO Contribution = $190,000,000; AC Yr 4 of 6; Adjustments / 1570 Boston Region Multiple 6 STP $ 28,184,400 $ 22,547,520 $ 5,636,880 AVENUE WITH THE UNION SQUARE SPUR funding flexed to FTA; match provided by local Pass-throughs contributions NEEDHAM-NEWTON- RECONSTRUCTION -

SENATE ...No. 2376

SENATE . No. 2376 Senate, July 24, 2012 -- Text of the Senate amendment, printed as amended as a new text for the House bill financing improvements to the commonwealth’s transportation system (House, No. 4193) The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _______________ In the Year Two Thousand Twelve _______________ 1 SECTION 1. To provide for a program of transportation development and improvements, 2 the sums set forth in sections 2 to 2C, inclusive, for the several purposes and subject to the 3 conditions specified in this act, are hereby made available, subject to the laws regulating the 4 disbursement of public funds. The sums appropriated in this act shall be in addition to any 5 amounts previously appropriated and made available for these purposes. 6 SECTION 2. 7 MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 8 Highway Division 9 6121-1215 For projects on the interstate federal aid highway system; provided, that funds 10 may be expended for the costs of these projects including, but not limited to, the nonparticipating 11 portions of these projects and the costs of engineering and other services essential to these 12 projects, rendered by Massachusetts Department of Transportation employees or by consultants; 13 provided further, that amounts expended for department employees may include the salary and 14 salary-related expenses of these employees to the extent that they work on or in support of these 15 projects; provided, however, that the secretary of transportation shall maximize efforts to utilize 1 of 34 16 all available means to minimize -

Driving Directions Brigham and Women’S Hospital Newborn Intensive Care Unit 75 Francis Street Center for Women and Newborns, 6Th Floor Boston, MA (617) 732-5420

Driving Directions Brigham and Women’s Hospital Newborn Intensive Care Unit 75 Francis Street Center for Women and Newborns, 6th Floor Boston, MA (617) 732-5420 From the North: • Head South on Route 93. • Take exit 26 (Route 28/Route 3 North) toward Storrow Drive. • Keep left at the fork in the ramp. • Turn slight right onto Route 3 North. Merge onto Storrow Drive west. • Take the Fenway/Route 1 South exit (on left). • Stay in the left lane as you drive up the ramp. • At lights, bear right onto Boylston Street. • At third set of lights, bear left onto Brookline Avenue. • At fifth set of lights, turn left onto Francis Street. • The hospital is one block down on the left. From the West: • Head east on Massachusetts Turnpike. • Take Route 128 (I-95) south for approximately one mile. • Take Route 9 east for six miles. • Take a left onto Brookline Avenue (Brook House Condominiums will be on right). • At third set of lights, turn right onto Francis Street. • The hospital is one block down on the left. • Or stay on Massachusetts Turnpike east. • Take Huntington Avenue/Copley Square/Prudential Center exit, and bear left toward the Prudential. Follow Huntington Avenue west for approximately three miles. • At Longwood Avenue, turn right. • Take a left at Binney Street. Hospital will be on your left at Francis Street. From the South: • Head north on Route 3 (Southeast Expressway). • Take Massachusetts Avenue/Roxbury exit. • At end of ramp, cross Massachusetts Avenue onto Melnea Cass Boulevard. • At the 8th traffic light, take left onto Tremont Street. -

Bartlett Station Highlights

RETAIL OPPORTUNITY 2565 Washington Street | Roxbury, Massachusetts Bartlett Station Highlights • Located at the junction of Washington and Bartlett Streets with convenient access to Interstates 93 and 90 (Massachusetts Turnpike) • Approximately 73,000 people and 25,000 households within a one-mile radius of Bartlett Station • Approximately $216 million in public/private dollars have been invested in commercial and residential development in the neighborhood as of 2016 • Bartlett Station is just blocks away from the South End, within a mile to Boston’s Financial District and walking distance to Northeastern University, Roxbury Community College, Boston Medical Center and BU Medical School. Nearby neighborhoods of Mission Hill and Jamaica Plain are less than seven minutes away. • Located less than a five minute walk from Dudley Station, providing access from Dudley Square to Ruggles Station with MBTA Orange and Silver Line service to Downtown Boston. Dudley Square Station is the region’s busiest bus station and averages 30,000 passengers daily Washington Street: Building A Trade Area Overview SEAPORT BOULEVARD BACK BAY SUMMER STREET COMMONWEALTH AVENUE 2019 90 BOYLSTON STREET Estimated FENWAY 93 SOUTH BOSTON COLUMBUS AVENUE SOUTH END 1 WEST BROADWAY Demographics TREMONT STREET 3 LONGWOOD EAST FIRST STREET MEDICAL AREA AVENUE DORCHESTER WASHINGTON STREET HUNTINGTON AVENUE EAST BROADWAY ALBANY STREET RESIDENTIAL POPULATION L STREETL Dudley Station Jackson Square Roxbury Crossing Ruggles M EL D NE R A VA C LE 220,098 ASS BOU 30,000 daily passangers 5,828 daily entrances 4,727 daily entrances 10,433 daily entrances MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE DUDL EY S T R E HOUSEHOLDS E T BROOKLINE C O L W U ROXBURY M A 83,986 R B R U E S N A S V T WILLIAM T. -

Dudley Square Vision Initiative

City of Boston Dudley Square Vision Initiative Transportation Action Plan Prepared for: Boston Transportation Department Boston Redevelopment Authority Submitted by: Traffic Solutions, LLC 50 Franklin Street Suite 402 Boston, MA 02110 December 2009 DRAFT REPORT I Table of Contents Executive Summary . i Introduction . 1 Parking – Short Term . 2 Parking – Long Term . 7 Vehicular and Pedestrian Circulation – Short Term . 8 Vehicular and Pedestrian Circulation – Long Term . 20 Vehicular Circulation – Future Considerations . 34 Bicycle Accommodations . 36 Urban Design . 38 Public Transit . 45 I Executive Summary The Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) in conjunction with the phasing, timing, and coordination adjustments at six intersections in the Boston Transportation Department (BTD) has retained Traffic Solutions to vicinity of Dudley Square; pavement markings and signage upgrades; and develop a Transportation Action Plan as part of the larger Dudley Square accessibility compliance. Vision initiative. The focus of this Transportation Action Plan was to improve traffic flow, create safe pedestrian and bicycle environment, Prior to initiating this study, BTD has already performed optimization of optimize parking, facilitate bus transit operation, and enhance the character traffic signal operation within and near the project area. Based on the of the neighborhood. preliminary findings, some recommendations, such as provision of accessible ramps have already been implemented as well The study approach included identifying issues on a short-term and long- term level. In the short-term, improvements can be made with relative ease, The long-term improvements proposed in the Transportation Action Plan with a modest budget and staff, and within a relatively quick time frame. include modification to travel patterns within Dudley Square and associated Conversely, the long-term level improvements require capital outlay, geometric alterations. -

Forsyth Building Address: Directions To

Auditory Prostheses and Communication Laboratory Renaissance Park Garage Address: 835 Columbus Ave, Roxbury Crossing, MA 02120 Forsyth Building Address: 70 Forsyth St. Boston MA, 02115 Directions to the laboratory: From the north (via Route I-93 or Route 1) Take the Storrow Drive exit, and proceed to the Fenway exit. Follow signs for Boylston Street inbound, and bear right onto Westland Avenue. Turn right onto Massachusetts Avenue, proceed to the third traffic light, and turn right onto Columbus Avenue. The Renaissance Park Garage (see #62 on the campus map, is immediately one-half mile ahead on your right, at 788 Columbus Avenue. Once parked, exit the garage and cross Melnea Cass Blvd. Follow the footpath through the Columbus St. parking lot to the foot-bridge. Cross the bridge and head left (toward Ruggles T- stop). Once you reach the main road take a right onto Forsyth St. and proceed to 70 Forsyth St. (number 55 on the campus map). The department offices are located on the first floor of the Forsyth building. From the west (via Route 90, Massachusetts Turnpike) Take Exit 22 (Copley Square), and bear right. Proceed to the first traffic light, and turn right onto Dartmouth Street. Take the next right onto Columbus Avenue. The Renaissance Park Garage (see #62 on the campus map), is approximately one mile ahead on your right, at 788 Columbus Avenue. Once parked, exit the garage and cross Melnea Cass Blvd. Follow the footpath through the Columbus St. parking lot to the foot-bridge. Cross the bridge and head left (toward Ruggles t- stop). -

Parcel 9 + Parcel 10 Roxbury Massachusetts

BRAREQUEST FOR PROPOSALS Parcel 9 + Parcel 10 Roxbury Massachusetts CITY OF BOSTON Thomas M. Menino Mayor John F. Palmieri Director Clarence J. Jones Chairman Consuelo Gonzales-Thornell Treasurer Paul D. Foster Vice Chairman James M. Coyle Member Timothy J. Burke Member Brian P. Golden Executive Director/Secretary ONE CITY HALL SQUARE BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS 02201 APRIL 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ..............................................................................3 2 Site Location and Description ................................................4 3 Planning Context ......................................................................9 4 Development Goals ................................................................12 5 Urban Design ..........................................................................15 6 Submission Requirements ....................................................23 7 Selection Criteria & Process .................................................32 8 Terms and Conditions............................................................36 List of Appendices ......................................................................37 Community workshops 1. INTRODUCTION The Boston Redevelopment Authority (“BRA”) and the Massachusetts Divi- sion of Transportation (“MassDOT”) are pleased to issue this Request for Proposals (“RFP”) for the development of Parcels 9 and 10 located in the Roxbury Neighborhood of Boston. Parcels 9 and 10 are two of seven par- cels to be disposed of through the process described in