Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 38, No. 2 William B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

The Pennsylvania Assembly's Conflict with the Penns, 1754-1768

Liberty University “The Jaws of Proprietary Slavery”: The Pennsylvania Assembly’s Conflict With the Penns, 1754-1768 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the History Department in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in History by Steven Deyerle Lynchburg, Virginia March, 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Liberty or Security: Outbreak of Conflict Between the Assembly and Proprietors ......9 Chapter 2: Bribes, Repeals, and Riots: Steps Toward a Petition for Royal Government ..............33 Chapter 3: Securing Privilege: The Debates and Election of 1764 ...............................................63 Chapter 4: The Greater Threat: Proprietors or Parliament? ...........................................................90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................113 1 Introduction In late 1755, the vituperative Reverend William Smith reported to his proprietor Thomas Penn that there was “a most wicked Scheme on Foot to run things into Destruction and involve you in the ruins.” 1 The culprits were the members of the colony’s unicameral legislative body, the Pennsylvania Assembly (also called the House of Representatives). The representatives held a different opinion of the conflict, believing that the proprietors were the ones scheming, in order to “erect their desired Superstructure of despotic Power, and reduce to -

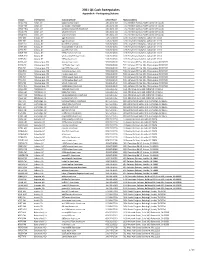

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station iHM Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM 1047kabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM -

Fall Newsletter 2014.Pub

September 2014 Heritage Headlines Volume 17, Issue 3 INSIDE Page 2 and 3: A VERY GOOD YEAR Upcoming Exhibits Last year was a very good year for the Candace Honored Heritage Center thanks to the warm support of Exhibit Workshop Wish List item our friends, Board members, volunteers, and guests. In 2013 more than 7,000 visitors came Page 4 and 5: to the Heritage Center to see our exhibits, Homeschool Workshops research their genealogy, and learn about local Adult and Children’s Education Programs history. Our collections grew as people donated treasured objects to be saved and shared with Page 6: future generations. Our educational programs Exile Meeting engaged children in understanding their heritage Friends Program Heritage Tour through fun activities. And our annual fund campaign achieved success, enabling the Heritage Center to maintain qualified staff and a Page 7: beautiful building to house our important collection, present our excellent programs, and Christmas Market welcome you! New Intern Public Speaking Program This summer, our Brown Bag Lunch series on Schwenkfelder and local history related topics was very popular. John P. Diefenderfer’s colorful paintings of Amish life in Lancaster Page 8: County can be enjoyed through September 28. Common Threads, our dazzling textile exhibition, in Day of Remembrance PA State Senate Honor collaboration with the Goschenhoppen Historians and the Mennonite Heritage Center, closes Buy a Brick! October 31 – don’t miss it! While you are here, enjoy a tour of historic architecture, captured in turn-of-the-century photographs by H. Winslow Fegley. Here, images of our Pennsylvania Page 9: German past have been preserved for posterity. -

The ^Penn Collection

The ^Penn Collection A young man, William Penn fell heir to the papers of his distinguished father, Admiral Sir William Penn. This collec- A tion, the foundation of the family archives, Penn carefully preserved. To it he added records of his own, which, with the passage of time, constituted a large accumulation. Just before his second visit to his colony, Penn sought to put the most pertinent of his American papers in order. James Logan, his new secretary, and Mark Swanner, a clerk, assisted in the prepara- tion of an index entitled "An Alphabetical Catalogue of Pennsylvania Letters, Papers and Affairs, 1699." Opposite a letter and a number in this index was entered the identifying endorsement docketed on the original manuscript, and, to correspond with this entry, the letter and number in the index was added to the endorsement on the origi- nal document. When completed, the index filled a volume of about one hundred pages.1 Although this effort showed order and neatness, William Penn's papers were carelessly kept in the years that followed. The Penn family made a number of moves; Penn was incapacitated and died after a long illness; from time to time, business agents pawed through the collection. Very likely, many manuscripts were taken away for special purposes and never returned. During this period, the papers were in the custody of Penn's wife; after her death in 1726, they passed to her eldest son, John Penn, the principal proprietor of Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia, there was another collection of Penn deeds, real estate maps, political papers, and correspondence. -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

The Scandalous Indian Policy of William Penn's Sons: Deeds and Documents of the Walking Purchase

THE SCANDALOUS INDIAN POLICY OF WILLIAM PENN'S SONS: DEEDS AND DOCUMENTS OF THE WALKING PURCHASE BY FRANCIS JENNINGS* I N1737 Thomas Penn and James Logan produced a show that came to be called the Walking Purchase or Indian Walk. This much-described incident ostensibly was the fulfillment of a con- tract by which some Lenape Indians had sold a quantity of lands to be measured by a man walking for a day and a half from a fixed starting point. Penn and Logan forced the Walk upon un- willing and resentful Indians who charged fraud consistently from the day of its performance until they finally received compensa- tion twenty-four years later. During this period the anti-proprietary forces in Pennsylvania came to believe that the Walk was a cause of Indian hostilities in the French and Indian War, and they used it as the basis for a political campaign against Thomas Penn which led to a petition by Benjamin Franklin for a royal inquiry. In 1762 the Crown's commissioner, Sir William Johnson, presided over a turbulent hearing during which the chief Indian spokesman withdrew his charge that Thomas Penn had forged the Walk deed; but Johnson paid the Indians anyway at the end of the inquiry out of Thomas Penn's funds, thus raising some suspicions about the nature and purpose of the proceedings. There has been much contention over these highly dramatic events. Using the voluminous justifications prepared by Penn's lawyers and administrators, one school has held that Penn was libeled unscrupulously for the partisan purposes of some schem- ing Quakers working with that greatest schemer of them all, Benjamin Franklin. -

A Timeline of Bucks County History 1600S-1900S-Rev2

A TIMELINE OF BUCKS COUNTY HISTORY— 1600s-1900s 1600’s Before c. A.D. 1609 - The native peoples of the Delaware Valley, those who greet the first European explorers, traders and settlers, are the Lenni Lenape Indians. Lenni Lenape is a bit of a redundancy that can be translated as the “original people” or “common people.” Right: A prehistoric pot (reconstructed from fragments), dating 500 B.C.E. to A.D. 1100, found in a rockshelter in northern Bucks County. This clay vessel, likely intended for storage, was made by ancestors of the Lenape in the Delaware Valley. Mercer Museum Collection. 1609 - First Europeans encountered by the Lenape are the Dutch: Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing under the Dutch flag, sailed up Delaware Bay. 1633 - English Captain Thomas Yong tries to probe the wilderness that will become known as Bucks County but only gets as far as the Falls of the Delaware River at today’s Morrisville. 1640 - Portions of lower Bucks County fall within the bounds of land purchased from the Lenape by the Swedes, and a handful of Swedish settlers begin building log houses and other structures in the region. 1664 - An island in the Delaware River, called Sankhickans, is the first documented grant of land to a European - Samuel Edsall - within the boundaries of Bucks County. 1668 - The first grant of land in Bucks County is made resulting in an actual settlement - to Peter Alrichs for two islands in the Delaware River. 1679 - Crewcorne, the first Bucks County village, is founded on the present day site of Morrisville. -

Fleetwood Man Wanted by Police Found

Patriot Want Ads Cost Little Subscribe Now to The Patriot A nd Help You to Sell, Buy It Carries All the News Or Rent Everything 1&ht Of the East Penn Valley * •* .. StRVWC KU r*i<WN, FLEETWOOD, TOPTOH AX2 SSSRtS^^ ***4S VOL. LXXXII KUTZTOWN, PA., THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 1957 Telephone 7343 NO. 43 WASHINGTON'S BIRTHDAY FRIDAY; FOUR EAST PENN Fleetwood Man Wanted By Police State Readying Papers To Transfer BANKS WILL BE CLOSED The four banking houses in the East Penn Valley will be closed j Friday in observance of Wash Found Dead Of Bullet Wound; Had College Tract For PNG Armory Use ington's Birthday. Two of them will also be closed Saturday. Papers are now going through i Last year an architect in the De j uf the contract when the construc Kutztown National Bank and the mills of various departments at partment of Military Affairs had tion program had to be halted. the Farmers Bank will be open Harrisburg which will ultimately re drawn a preliminary sketch of an for the usual Saturday banking Terrorized Woman With Gun Since the Federal government sult in the transfer of a site for a armory which would be suitable hours, 8:30 to 11 a.m. Both the pays up to 75 per cent of the cost National Bank of Topton and new Kutztown Armory, it was for the Kutztown unit of the Na I of Armory construction simple learned from the Capitol this week. tional Guard At that time, too. First National, Fleetwood, will State Police yesterday morning escapade when at gunpoint he The bullet entered the head just stopped at Moselem Springs. -

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

2018 3 9 Catalog

LANCASTER MENNONITE HISTORICAL SOCIETY’S BENEFIT AUCTION OF RARE, OUT-OF-PRINT, AND USED BOOKS FRIDAY, MARCH 9, 2018, AT 6:30 P.M. TEL: (717) 393-9745; FAX: (717) 393-8751; EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.lmhs.org/ The Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society will conduct an auction on March 9, 2018, at 2215 Millstream Road, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, one-half mile east of the intersection of Routes 30 and 462. The sale dates for the remainder of 2018 are as follows: May 11, July 13, September 14 and November 9. Please refer to the last page of the catalog for book auction procedures. Individual catalogs are available from the Society for $5.00 + $3.00 postage and handling. Persons who wish to be added to the mailing list for the rest of 2018 may do so by sending $15.00 with name and address to the Society. Higher rates apply for subscribers outside of the United States. All subscriptions expire at the end of the calendar year. The catalog is also available for free on our web site at www.lmhs.org/auction.html. 1. Bender, Harold S. Conrad Grebel, c. 1498-1526, the Founder of the Swiss Brethren, Sometimes Called Anabaptists. Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite History, no. 6, vol. 1. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1950. xvi, 326pp (b/w ill, bib, ind, copy of author, syp, gc). 2. Friedmann, Robert. Mennonite Piety Through the Centuries: Its Genius and Its Literature. Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite History, no. 7. Goshen, Ind.: Mennonite Historical Society, 1949. xv, [i], 287pp (fp, b/w ill, bib, ind, presentation copy signed by author, syp, gc). -

Resources for Teachers John Trumbull's Declaration Of

Resources for Teachers John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence CONVERSATION STARTERS • What is happening with the Declaration of Independence in this painting? o The Committee of Five is presenting their draft to the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock. • Both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson apparently told John Trumbull that, if portraits couldn’t be painted from life or copied from other portraits, it would be better to leave delegates out of the scene than to poorly represent them. Do you agree? o Trumbull captured 37 portraits from life (which means that he met and painted the person). When he started sketching with Jefferson in 1786, 12 signers of the Declaration had already died. By the time he finished in 1818, only 5 signers were still living. • If you were President James Madison, and you wanted four monumental paintings depicting major moments in the American Revolution, which moments would you choose? o Madison and Trumbull chose the surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, the Declaration of Independence, and the resignation of Washington. VISUAL SOURCES John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence (large scale), 1819, United States Capitol https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Declaration_of_Independence_(1819),_by_John_Trumbull.jpg John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence (small scale), 1786-1820, Trumbull Collection, Yale University Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/69 John Trumbull and Thomas Jefferson, “First Idea of Declaration of Independence, Paris, Sept. 1786,” 1786, Gift of Mr. Ernest A. Bigelow, Yale University Art Gallery https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/2805 PRIMARY SOURCES Autobiography, Reminiscences and Letters of John Trumbull, from 1756 to 1841 https://archive.org/details/autobiographyre00trumgoog p.