The Present State of Things: Class Struggle in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unions Talk Tough at US Social Forum

Starbucks charged Chicago Couriers: doing Boycott Molson beer, IWW meets Bangladeshi again for firing IWW solidarity unionism support Alberta strike garment workers 5 6-7 9 11 INDUSTRIAL WORKER OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER O F T H E I N D U S T R I A L W O R K E R S O F T H E W O RLD August 2007 #1698 Vol. 104 No. 8 $1 / £1 / €1 Unions talk tough at US Social Forum By Jerry Mead-Lucero Big Labor’s involvement in the social nizers were forced to compromise with the ILO (International Labour Organi- “What is happening in America forum process, since the first few World police on a much less confrontational zation). In April, the ILO declared the to workers today is the result of a Social Forums in Porto Alegre, Brazil, route due to the opposition of much North Carolina ban on public sector thirty year sustained, intentional, has served as a way for the AFL-CIO and of Atlanta ’s business community. A collective bargaining a violation of strategic, assault on workers, unions, many of the union internationals to mix destination in the original plan was international labor standards and called our quality of life and our standard of and mingle with activists from a broad Grady Hospital, where the green-shirted for repeal of North Carolina General living. It has been a class war against range of social struggles. The same can members of Local 1644 had planned Statute 95-98, the basis of the ban. workers and it is time we engage that be said of the relatively impressive sup- to express their opposition to a recent Traditionally, social forum planners class war and fought back.” port given to the first USSF by organized decision by the Chamber of Commerce and participants will engage in a num- These words were met by a labor. -

Solidarity Unionism : Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below, Second Edition Pdf Free Download

SOLIDARITY UNIONISM : REBUILDING THE LABOR MOVEMENT FROM BELOW, SECOND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Staughton Lynd | 122 pages | 21 May 2015 | PM Press | 9781629630960 | English | Oakland, United States Solidarity Unionism : Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below, Second Edition PDF Book There is a remainder mark on top of the text block and appx. An oral history project of the working class undertaken with his wife inspired Lynd to earn a JD from the University of Chicago in One of them, an electric lineman, returned with a fellow worker to help bring electric power to small towns in northern Nicaragua. Zachary McDargh rated it really liked it Aug 06, Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Editors: Aziz Choudry and Adrian A. While many lament the decline of traditional unions, Lynd takes succor in the blossoming of rank- and-file worker organizations throughout the world that are countering rapacious capitalists and those comfortable labor leaders that think they know more about work and struggle than their own members. Isn't the whole point of forming a union to get a written collective bargaining agreement? New books! Far from prefiguring a new society, they are institutional dinosaurs, resembling nothing so much as the corporations we are striving to replace. Staughton Lynd practiced employment law for twenty years in Youngstown, Ohio. Kersplebedeb Left-Wing Books and more! This has been the model of the Industrial Workers of the World for over years and is also the way many workers centers operate. Lynd doesn't seem to consider the possibility that some workers may not be looking for constant class warfare on the job, and that settling a decent contract offers a much needed respite to lock-in gains. -

Revitalization Strategy of Labor Movements

<Abstract> Revitalization Strategy of Labor Movements Korea Labour & Society Institute 1. The stagnation of trade union movement is an international phenomenon. The acceleration of globalization and technological innovation, the expanding predominance of service industries in the economies of advanced industrialised countries and the concomitant shifts in the composition of employment, and the deepening of neoliberal policy climate in the context of economic slow-down, which have prevailed since the 1980s, have all contributed to the stagnation of trade union movement in most countries across the world. This phenomenon has been captured through such indicators as the decline in union density, the weakening of political and social influence, and decentralisation of collective bargaining have been, among others. The trade union movements in different countries have, however, since 1990s, developed and undertaken a variety of "revitalisation"strategies to wake out of the stagnation. The specific shape of the revitalisation strategy were informed by the specific nature of the challenge the unions faced, the characteristics of the industrial relations system in which the unions were constituted, and the historical identity individual trade union movement espoused. However, organising efforts, internal innovation, social partnership, strengthening of political campaign activities, and extension of solidarity with civil society and community networks have featured as common components in most of the varied strategies. The evidence of these common initiatives points to the existence of some common challenge that courses through the country-specific situations the trade union movements in different countries have found themselves in. This study examines the strategic responses of the trade unions in the selected countries have undertaken in the face of the challenges faced by the international labour movement. -

Korea Observer 49-1 4차편집본

Union Strategy to Revitalize Weakening Worker Representation in South Korea 83 Union Strategy to Revitalize Weakening Worker Representation in South Korea* Hyung-Tag Kim**, Young-Myon Lee*** The rapid growth of South Korea's labor unions after 1987 Great Labor Offensive has been considered as one of the highest achievements in labor movement history. Yet now the social influence of labor unions in South Korea has been starkly reduced. For example, wage gaps between regular and non-regular workers and between workers at large and small companies have expanded, and union density as well as the application rate for collective agreements has fallen to about 10%. Rapid and dramatic changes in industrial structure and employment types coupled with regulatory limitations to collective agreement protections and application have reduced the appeal of union membership for many. And Korean unions have not seemed to adapt: although union membership is markedly industry-level, collective agreements are applied and managed within a traditional company-level IR framework. Unionism in South Korea needs urgent revitalization. The authors recommend this revitalization should proceed through institutional changes for improving workers' representation and through more also active organizing activity, but primarily it should happen through restoring a sense of solidarity among workers in the most basic sense. Key Words: labor union, employee representation, union revitalization strategy I. Past History and Current Status of Unionism in South Korea After the Great Labor Offensive during 1987 – 1989, Korea labor union movement achieved worldwide fame with its militancy. It had been considered as a successful example of creating new horizon under the situation of declining global labor union movement with such as COSATU of South Africa and CUT of Brazil. -

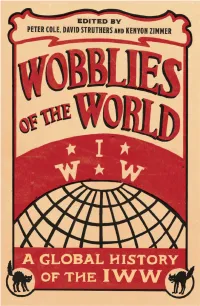

I Wobblies of the World a Global History of the IWW

WOBBLIES OF THE WORLD i Wobblies of the World A Global History of the IWW Edited by Peter Cole, David Struthers, and Kenyon Zimmer First published 2017 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Peter Cole, David Struthers, and Kenyon Zimmer 2017 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 9960 7 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 9959 1 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0151 7 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0153 1 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0152 4 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Curran Publishing Services, Norwich, England Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 Part I: Transnational Influences on the iww 27 1 “A Cosmopolitan Crowd”: Transnational Anarchists, the iww, and the American Radical Press 29 Kenyon Zimmer 2 Sabotage, the iww, and Repression: How the American Reinterpretation of a French Concept Gave Rise to a New International Conception of Sabotage 44 Dominique Pinsolle 3 Living Social Dynamite: Early Twentieth-Century iww– South Asia Connections 59 Tariq Khan 4 iww Internationalism and Interracial Organizing in the Southwestern United States 74 David M. -

Labor Law for the Rank and Filer

Labor Law for the Rank and Filer Building Solidarity While Staying Clear of the Law (2nd Edition) Staughton Lynd and Daniel Gross Have you ever felt your blood boil at work but lacked the tools to fight back and win? Or have you acted together with your co-workers, made progress, but wondered what to do next? If you are in a union, do you find that it operates top-down just like the boss and ignores the will of its members? Labor Law for the Rank and Filer: Building Solidarity While Staying Clear of the Law is a guerrilla legal handbook for workers in a precarious global economy. It demonstrates how a powerful model of organizing called “soli- darity unionism” can help workers avoid the pitfalls of the legal system and use direct action to win. Blending cutting-edge legal strategies for winning justice at work with a theory of dramatic social change from below, Staughton Lynd and Daniel Gross deliver a practical guide for making work better while reinvigorating the labor movement. The book examines specific cases concerning fundamental labor rights and includes a section SUBJECT CATEGORY on tactics and principles of practicing solidarity unionism. Illustrative stories LABOR/ of workers’ struggles make the legal principles come alive. POLITICS The New York Times has reported on the book’s importance in recent PRICE and ongoing labor organizing in the tech industry—for example among $12.00 employees of Google, Kickstarter, and Uber, whose union campaigns ISBN were influenced by ideas gleaned from Labor Law for the Rank and Filer. -

Labor Law for the Rank&Filer: Building Solidarity While Staying Clear of the Law

Labor Law for the Rank&Filer: Building Solidarity While Staying Clear of the laW By staughton lynd&daniel gross PM PRESS Labor Law for the Rank Filer: Building Solidarity While Staying Clear of& the laW By Staughton Lynd & Daniel Gross Copyright © 2008 Staughton Lynd & Daniel Gross This edition copyright © 2008 PM Press All Rights Reserved Designed by Courtney Utt Special thanks to Alice Lynd Published by: PM Press, PO Box 23912, Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org ISBN: 978-1-60486-033-7 Library Of Congress Control Number: 2008931841 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the USA on recycled paper. TABLE of CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................... 005 chapter 1 ................................................................007 On Being Your Own Lawyer chapter 2 ...............................................................015 Where Do Workers’ Rights Come From? chapter 3................................................................023 The Basic Labor Laws chapter 4 ...............................................................035 A Rank and Filer’s Bill of Rights The Right to Act Together The Right to Speak and Leaflet The Right to Grieve and Briefly to Stop Work The Right Not to Cross a Picket Line The Right to Refuse Unsafe Work The Right to Strike The Right to Be Represented The Right to Fair Representation The Right to Equal Treatment The Right Not to Be Sexually Harassed The Right to Be Free from Threats, Interrogation, Promises and Spying, and Not to Be Retaliated Against The Right to Be Radical chapter -

Wobblies of the World: a Global History of The

WOBBLIES OF THE WORLD i Wildcat: Workers’ Movements and Global Capitalism Series Editors: Peter Alexander (University of Johannesburg) Immanuel Ness (City University of New York) Tim Pringle (SOAS, University of London) Malehoko Tshoaedi (University of Pretoria) Workers’ movements are a common and recurring feature in contemporary capitalism. The same militancy that inspired the mass labour movements of the twentieth century continues to define worker struggles that proliferate throughout the world today. For more than a century labour unions have mobilised to represent the political- economic interests of workers by uncovering the abuses of capitalism, establishing wage standards, improving oppressive working conditions, and bargaining with em- ployers and the state. Since the 1970s, organised labour has declined in size and influ- ence as the global power and influence of capital has expanded dramatically. The world over, existing unions are in a condition of fracture and turbulence in response to ne- oliberalism, financialisation, and the reappearance of rapacious forms of imperialism. New and modernised unions are adapting to conditions and creating class-conscious workers’ movement rooted in militancy and solidarity. Ironically, while the power of organised labour contracts, working-class militancy and resistance persists and is growing in the Global South. Wildcat publishes ambitious and innovative works on the history and political econ- omy of workers’ movements and is a forum for debate on pivotal movements and la- bour struggles. The series applies a broad definition of the labour movement to include workers in and out of unions, and seeks works that examine proletarianisation and class formation; mass production; gender, affective and reproductive labour; imperialism and workers; syndicalism and independent unions, and labour and Leftist social and political movements. -

The Working Class and the Employing Class Have Nothing in Common,” Before Calling for an End to the Wage System and Capitalism

“THE WORKING CLASS AND THE EMPLOYING CLASS HAVE NOTHING IN COMMON:” THE CONSTITUTIVE RHETORIC OF THE IWW A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF THE ARTS BY: AUSTIN FLEMING ADVISOR: DR. KRISTEN L. MCCAULIFF BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, IN MAY 2018 ii Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to Dr. Kristen McCauliff for your support, patience, and mentorship. I could not have completed this thesis without your guidance, and throughout this process my writing skills have grown immensely. I will miss our weekly meetings and your encouraging words. Thank you for always listening to my rants and talking me down from the ledge. To Dr. Beth Messner and Dr. Sarah Vitale, my thesis committee members, thank you for your valuable input and time dedicated to this project. Your contributions have expanded the scope of my work, providing an interdisciplinary base which will guide my future work. To Dr. Glen Stamp, thank you for your willingness to stop and talk, be it about future plans or the Simpsons. Thank you for helping me learn the rich history of this discipline. I entered this program knowing little about communication studies and have now found an intellectual tradition to call home. I would also like to thank Dr. Katherine Denker for your unwavering support. You have never failed to provide me encouragement, and often see a light within me that I am unable to see myself. You have helped open doors for me that I wouldn’t have thought possible. Thank you for your continued guidance. -

Union-Buster's Analysis of IWW

Union-buster's analysis of IWW Article about the IWW from union-busting law firm, Seyfarth Shaw LLP which we reproduce for reference. 3. IWW’s Union Organizing Campaign against Jimmy John’s: The End or a Beginning for More Fast Food and Restaurant Organizing? Many restaurant employers, in particular owners of fast-food restaurants, rarely think about the possibility of unionization these days. While the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is using rulemaking and case precedent to make it easier for employees to organize, the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA) legislation is basically dead. UNITE HERE, the big player in the restaurant arena, is coming off of a difficult divorce between warring factions, is mired in never-ending hotel negotiations, and seems more focused on organizing larger locations pursuant to neutrality/card check agreements. The percentage of the workforce that is unionized in the private sector is at an all-time low, and while the number of representation petitions against restaurants has increased in the past few years, the numbers are still extremely low in any given year. That being said, fast food restaurant owners and operators should take heed of the recent organizing campaign in Minneapolis against ten Jimmy John’s locations. The Wobblies are at it again. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as the Wobblies, a union you may have read about in history class, has never gone away. In 2004, they started organizing baristas at Starbucks, created the IWW Starbucks Workers Union, and have had run-ins with Starbucks at locations in places such as New York City, Chicago, Minneapolis, Grand Rapids, Maryland, and even Omaha. -

Solidarity Unionism at Starbucks Global Economy

WOBBLIES ZAPATISTAS: CONVERSATIONS ANARCHISM,& MARXISM RADICALon HISTORY Wobblies and Zapatistas& offers the reader an encounter between two generations and two traditions. Andrej Grubacic is an Wanarchist from the Balkans. Staughton Lynd is a lifelong pacifist, influenced by Marxism. They meet in dialogue in an effort to bring together the anarchist and Marxist traditions, to discuss the writing of history by those who make it, and to remind us of the idea that “my country is the world.” Encompassing a Left libertar- ian perspective and an emphatically ac- tivist standpoint, these conversations are meant to be read in the clubs and affinity groups of the new Movement. PRODUCT DETAILS: The authors accompany us on Authors: Staughton Lynd & a journey through modern revolu- Andrej Grubacic tions, direct actions, anti-globalist Publisher: PM Press counter summits, Freedom Schools, Published: Sept 2008 Zapatista cooperatives, Haymarket ISBN: 978-1-60486-041-2 UNIONISM and Petrograd, Hanoi and Belgrade, Format: Paperback “intentional” communities, wildcat Page Count: 300 STARBUCKS strikes, early Protestant communi- Size: 8 by 5 ties, Native American democratic s idarity Subjects: History, Politics practices, the Workers’ Solidar- ity Club of Youngstown, occupied a factories, self-organized councils PRAISE: DANIEL GROSS STAUGHTON LYND and soviets, the lives of forgotten “There’s no doubt that we’ve lost much of revolutionaries, Quaker meetings, our history. It’s also very clear that those in antiwar movements, and prison re- power in this country like it that way. Here’s CARTOONS TOM KEOUGH bellions. Neglected and forgotten a book that shows us why. It demonstrates & Tnot only that another world is possible, but with moments of interracial self-activity are brought to light. -

Workplace Struggles of Precarious Migrants in Thailand

Solidarity Formations Under Flexibilisation: Workplace Struggles of Precarious Migrants in Thailand Stephen Campbell, University of Toronto, Canada ABSTRACT Recent scholarship on precarious labour has called attention to global transformations in employment regimes, which have given management greater freedom in setting the terms of work. Such ‘flexibility’ in employment is associated with a decrease in work, wage and livelihood security; more temporary, rather than open-ended, job contracts; a roll-back of employment benefits; heavy restrictions on workers’ collective organisation; and a greater reliance on migrant labour. To date, scholars have mostly emphasised the negative impact this transformation has had on workers’ solidarity. However, as this article highlights, flexibilisation can also function as an enabler of solidarity. Presenting an ethnographic case study of a workplace struggle at an export processing zone in northwest Thailand, it is argued that where flexible labour regimes incite shared grievances among workers and occlude the representative role of trade unions officials, they have facilitated self-organised struggles among workers based on a clear sense of common cause. KEYWORDS flexibilisation, migration, Myanmar, precarious labour, Thailand, workplace struggle When describing the social dynamics of workers’ collective action, Myanmar migrants in Thailand have repeatedly drawn on the metaphor of a straw fire (kauk-yo-mi). The idea is that workplace grievances and discontent are widespread without any collective response. Yet a sudden spark can ignite a blaze of mass mobilisation, with those employed at a given workplace rushing into a movement of collective rebellion. Within this observation is recognition of both challenges and opportunities for workplace struggles under local ‘flexible’ employment regimes.