Historical Outline of Agriculture in Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Basic Survey on Agricultural and Rural Development by Progress Stage in Asian Countries

Assigned by Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Report on the Basic Survey on Agricultural and Rural Development by Progress Stage in Asian Countries LAO PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Focus on Savannakhet and Champasak MARCH 1998 The Asian Population and Development Association The Middle in the front Mr. Khamphiou Vissapra, Deputy Director General, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Behind- from the left Dr. Seiichi fukui, Survey Team Leader Mr. Oudone Sisingkham, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Mr. Akihiko Oono, Survey Team Member Mr. Mitsuru Sonoe, Survey Team Member Mr. Osamu Kusumoto, Survey Team Member From the Left Mr. Akira Hashimoto, JICA Expert Mr. Tanousay Ounthouang, Deputy Director General, Department of Irrigation, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Water Reservoir KM35 (Savannakhet) Field Survey at DKK Village (Savannakhet) Pumping Facility at ND village (Champasak) Field Survey at ND Village Se Don River in Rainy Season Se Don River in Dry Season MAP of LAO P.D.R. 1 " I I N....•"--... l- 102° 1041, ,01 f , CHINA LAO PEOPLE'S s!, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC --- • •— International boundary 0 Town, village -22° 22°- •—•—• Provincial boundary Principal road Ph-longsall :\ 0 National capital Secondary road • Provincial capital 4' Airport PHONbSALI 0 50 100 150km ' L UAW.' T A ' 0 50 100mi Louan Namtha ••• V1N 4L.)udo kengkbaurt /1BOKE0 mong 5, .‘• say') -/ 4 s Sam Noila • I aOU r .MSAY Gulf of Tonkin ANG PRA •UAPI -IAN Pakbang 20°- Louang Probang,„/„. XIENG KI-10 ANG •.....-• • 5. " 11 -1 4 Phonsavan ,-. ..-.,_,, S'arboury ., Kaai N A.., • .....- .\ ,...).... VA , \-... Vang tong ‘._ - tel f IANE ......;.--. •-......(- '..--,. Nam (.. A.. --„, -..„„. ;Yvon I -,4,. -

Agricultural Environment of the Back Land of Nagura Bay, Okinawa Prefecture"

"Agricultural Environment of the Back Land of Nagura Bay, Okinawa Prefecture" 著者 "KATAYAMA Tadao C., SHINAGAWA Akio, HIGASHI Teruo" journal or 南海研紀要 publication title volume 6 number 1 page range 37-55 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/15660 Mem. Kagoshima Univ. Res. Center S. Pac. Vol.6, No. 1, 1985 37 Agricultural Environment of the Back Land of Nagura Bay, Okinawa Prefecture* Tadao C. Katayama**, Akio Shinagawa*** and Teruo Higashi*** Abstract The agricultural environment of the back land of Nagura Bay, Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture, /'. e., upland factors and cropping systems were discussed on the basis of references and observation in the area. There is a rapid consumption and a high turnover rate for organic matter, nutrients, minerals. To improve soil preserva tion, it is recommended utilization of natural topographical features and plants is more suitable than building artificial structures. Plants with a tap root and deep-rooted trees are good examples of natural stabilization structures. In comparison to the agricultural practices dominated by hand labor and small machines, procedures utilizing large machines are disadvantageous, because they increase the amount of times the land remains bare and they reduce the necessary elasticity in farm practices. It is recom mended to increase the agricultural development cautiously to preserve the environ ment and to keep the local population consensus. Introduction Ishigaki Island lies between 124°04'E and 124°20'E longitude and 24°19'N and 24° 36'N latitude (Fig. 1). In general, Ishigaki Island is said to be characteristic of a sub-tropical region. Because of its sub-tropical nature, it has higher temperatures and more abundant solar energy in comparison with Japan proper. -

Agricultural/Rural Development

12.Agricultural/ Rural Development Mycotoxin Inspection in Food GROUP 088000 ᮉ᭞᭳᭘᭢ᮞΜ˟͓؊ Agricultural/Rural DevelopmentOther Agricultural/Rural Development Issues Health Health System 4 participants ዋ English OBJECTIVE TARGET ORGANIZATION / GROUP The purpose of the program is to enable the participants to understand the basic Target Organizations knowledge and techniques for the control and management of mycotoxins. After Food inspection organization in developing this program, they are expected to be able to apply them in their respective countries countries. Target Group Technical officers or inspectors presently engaged in food inspection with at least 3 years of experience PROGRAM Jan.26.2009May.9.2009 CONTENTS PERIOD Lectures: IMPLEMENTING KOBE INSTITUTE OF HEALTH, () Food sanitation law and food inspection PARTNER NAGOYA CITY PUBLIC HEALTH (2) General view of mycotoxins INSTITUTE (3) Introduction to fungi JICA CENTER JICA Hyogo (4) Isolation and identification of fungi COOPERATION (5) Aspergillus flavus contamination of groundnuts and maize PERIOD 20052009 (6) Fusarium contamination of wheat and maize (7) Sampling for mycotoxins (8) Analysis of mycotoxins (9) Control of mycotoxins (0) Analysis of food preservatives REMARKS Practical exercises: () Method of the isolation and identification of mycotoxins-producing fungi (2) Analysis of mycotoxins such as aflatoxins and fusarium mycotoxins (3) Analysis of food preservatives Agrobiotechnology GROUP 0880003 ᭛ᮘ᭻᭕᭱᭚᭹ᮘ᭣ᮧ Agricultural/Rural DevelopmentAgricultural Development 6 participants ዋ English OBJECTIVE TARGET ORGANIZATION / GROUP The purpose of the program is to enable experts to make the best use of Target Organizations bio-resources in the field of agrobiotechnology (livestock, higher plants, Research institute for microbiology and higher microorganisms) in which continuous technological innovations and higher animals/plants applicability are expected in the near future. -

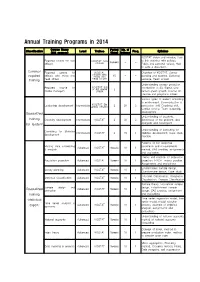

Annual Training Programs in 2014

Annual Training Programs in 2014 Course Name Period No. of Classification Level Trainee Freq. Syllabus (124 courses) (days) trainees KOSTAT vision and mission, How Required course for new to link statistics with policies, KOSTAT new 4weeks - - officials officials Public and personal values, How to write a document. Common Required course for KOSTAT Overview of KOSTAT, Survey officials who required officials who move into move into 15 - - planning and practice, Statistical training head offices head offices package, Team project Understanding privacy protection, Required course for KOSTAT 3rd Introduction to Six Sigma, Low or 4th grade 3 - - middle managers official carbon green growth, Course on creative and pragmatic values Various types of leaders according to environment, Communication & KOSTAT 5th Leadership development Intermediate grade officials 3 20 2 persuasion skill, Coaching skill, Conflict solving, Team leadership Specialized development Understanding of creativity, training Creativity development Intermediate KOSTAT 3 30 2 Awareness of the problem, idea (for leaders) divergent and convergent Understanding of consulting for Consulting for Statistics Intermediate KOSTAT 3 15 1 statistics development, Case study, development Practice Patterns of non response, Missing data processing parametric and no-parametric Advanced KOSTAT 16weeks 10 1 & analysis method, SAS practice, assignments and evaluation Theory and practice for population Population projection Advanced KOSTAT 16weeks 10 1 projection, EXCEL macro practice, Assignments -

713, Hanbat-Daero, Seo-Gu, Daejeon(302-847), Republic

Sunsa Dunsan Intercity Dunsan Gov. Complex Prehistoric Site Bus Terminal Express Bus Terminal Daejeon Gov. Complex Gov. Complex South Gate Statistical Underpass Training Institute Gov. Complex South Gate Gov. Complex Sub. Sta EXIT 3Gate Gov. Complex Dunsan Police ③④Sub.Sta Gov. Complex Sub. Sta Gov. Complex ②① Sub.Sta E-Mart Daejeon City Hall Bus : 102, 108, 116, 211, 301, 318, 604, 605, 618, 705, 706, 918 Subway : Gov. Complex Sub. Sta EXIT 3Gate Address : 713, Hanbat-daero, Seo-gu, Daejeon(302-847), Republic of Korea http://sti.kostat.go.kr Creative Core Personnel! Leading the Knowledge-Information Age in the 21st Century Prepare Statistical Competency in STI of KOSTAT WORLD BEST STATISTICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE Ⅰ Introduction to STI 04 Mission & Vision Key Strategies & Major Tasks 05 Organization Chart History Ⅱ Curriculum 06 Courses on Statistical/Statistical users/ Informatization/Foreigners/Custom-tailored Cyber-learning & Mobile-learning 08 e-Learning Center Ⅲ Annual Training Programs in 2014 10 Annual Training Programs Ⅳ Facilities 23 Various lecture facilities 24 Facilities for various conferences and events 25 Library and relaxation 26 Physical and other facilities 27 Accommodation 28 Statistics Center building layout STI Jeju Training Center Ⅰ Introduction to STI Mission & Vision Mission Foster global statistical leader Offer statistical training in harmony with citizens Vision World’s Leading Statistical Training Institute Key Strategies & Major Tasks <Key Strategies> <15 Major Tasks> 04 Statistical Training Institute(STI) Organization Chart Director General of Statistical Training Institute Statistical Training Advisory Committee Training Planning Training Management Outsourced area Division Division Building management Education Administ- General General Training General Professional Cooper- rative Manage- Affairs Planning Statistics Statistics e-Learning ation Support ment History ’91. -

Republic of Uganda―

Assigned by Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Base Study on the Impact of the Population on Agriculture and Rural Environment ―REPUBLIC OF UGANDA― Focus on Mabira Forest Reserve and its Vicinity in Mukono District March 2008 The Asian Population and Development Association (APDA) -II- Uganda map -I- Survey area map -II- Front Hon. Dr. Chris Baryomunsi Uganda Parliamentarians Forum on Food security, Population and Development (Uganda Parliamentarian) Back from left Ms. Yoko ICHIJO Survey Member Mr. Wamala Buyungo Musa Uganda Parliamentarians Forum on Food security, Population and Development, Programme Coordinator Mr. Masanori TAKEMOTO Survey Member Ministry of Water and Environment Center Hon. Jesca Eriyo Minister of State for Environment National Forest Authority (NFA) Front from Left Ms. Fiona Driciru Community Partnership Specialist Mr. Peter Kityo Field Services Specialist Back from right Mr. Shoichiro SHIRAISHI Survey Leader -III- Hearing Survey to a Village(LCI) Councilor at Target village Hearing Survey at the Village Roadside Store of Fuelwood near Target Villages -IV- Foreword This report is a compilation of the results of a survey conducted in the Republic of Uganda (hereinafter “Uganda”) by the Asian Population and Development Association (hereinafter “APDA”) under commission of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries for FY2007 entitled “Base Study on the Impact of the Population Problem on Agriculture and the Rural Environment.” Research and coordination was carried out mainly by the Survey Review Committee which was set up in APDA (led by Dr. Yonosuke Hara, Professor of National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies). The reduction of poverty and securing of environmental sustainability are pressing challenges of the Millennium Development Goals that require support from the international community and are positioned as priority issues in Japan’s ODA Outline. -

1. Compost Producing Facility in Sarabetsu Village, Tokachi District, Hokkaido, JAPAN

Briefing text for the visiting excursion to the 1. Compost producing facility in Sarabetsu village, Tokachi district, Hokkaido, JAPAN Translated from the pamphlet of JA Sarabetsu Kiyoshi Tsutsuki Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine 1. Outline of agriculture in Sarabetsu village In Sarabetsu village, located in the southern part of Tokachi plain, an average farmer possesses 43 ha of farm land and 3.4 tractors, which is deemed to be the largest scale agriculture in Japan. A large scale upland management including potato, sugar beet, wheat, and pulses, are mainly conducted in this village. Cropping of heavy vegetables carrot and Japanese radish is also increasing. On the other hand, dairy farming has a tendency to increase the number of cattle per a unit farmer but it is gradually decreasing as a whole due to the change to upland agriculture and also to the abandonment of agricultural management. For the promotion of agriculture, our village displays the following goals: 1) Promotion of upland agriculture by establishing a rotational cropping system and increasing soil fertility and build-up of a production center of vegetables. 2) Promotion of “clean agriculture” by the application of organic matter (fully matured compost) and by growing green manure. 3) Soil improvement program by promotion of drainage, fertilizer planning based on soil diagnosis. 4) Training and securing of breadwinner and successor of agriculture. 5) Measure for the promotion of dairy farming by introduction of dairy labor helpers and securing grasses and crude forage with good quality. 2. Build-up of good soil and the measure for environmental protection In accordance with the enlargement of the size of dairy farming management, the load to environment by the dairy excrement is increasing. -

Knowledge Co-Creation Program (Group & Region Focus)

Knowledge Co-Creation Program (Group & Region Focus) GENERAL INFORMATION ON Local Industry Development in Agricultural Regions by Strengthening Capacity of Management and Marketing (B) 課題別研修「農業地域における経営力、 マーケティング強化による地場産業振興(B)」 JFY 2019 NO. 201984715J002 / ID. 201984715 Course Period in Japan: From January 13th, 2020 to February 15th, 2020 This information pertains to one of the JICA Knowledge Co-Creation Program (Group & Region Focus) of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which shall be implemented as part of the Official Development Assistance of the Government of Japan based on bilateral agreement between both Governments. ‘JICA Knowledge Co-Creation Program (KCCP)’ as a New Start In the Development Cooperation Charter which was released from the Japanese Cabinet on February 2015, it is clearly pointed out that “In its development cooperation, Japan has maintained the spirit of jointly creating things that suit partner countries while respecting ownership, intentions and intrinsic characteristics of the country concerned based on a field-oriented approach through dialogue and collaboration. It has also maintained the approach of building reciprocal relationships with developing countries in which both sides learn from each other and grow and develop together.” We believe that this ‘Knowledge Co-Creation Program’ will serve as a center of mutual learning process. 1/16 I. Concept Background Most of developing countries have achieved economic growth; on the other hand, it caused social and environmental problems. To promote local industry sustainably, “business as usual does not work anymore. To realize sustainable development, we need creative and innovative strategies. This program aims to ensure the capacity development for the change leaders who try to practice sustainable rural development from aspects of its management and marketing skills in agricultural regions. -

12.Agricultural/ Rural Development

12.Agricultural/ Rural Development 12 Planning and Designing of Agricultural Statistics for Agricultural Policy Making PITD Trainers 1180046 農業政策立案のための農業統計企画・設計 Target Countries: 9 participants Sector: Agricultural/Rural Development/Agricultural Policy and System Sub-Sector: Language: English Appeal To develop the ability of making statistics that is the basis of planning of agricultural policy to be contributed to secure food in developing countries Objective / Output Target Organization / Group The ability of planning/designing for governmental officers in the department/bureau responsible for (1) Current Duties: Officers who are agricultural statistics, or agricultural policy making and/or food supply-demand planning is improved. specialists attached to or who hold the position of deputy (assistant to) head of the division in the Department/Bureau responsible (1) Developing the ability in agricultural policy making and food supply-demand planning towards for agricultural statistics, or agricultural policy sustainable agricultural production, and then possible to explain improvement plans for the participant’s making and/or food supply-demand planning, country. (2) Understanding necessity to improve agricultural statistics for policy making and food affiliated to the agricultural administration supply-demand planning, and possible to explain priority of future survey items to be collected in the agencies of the central government (ex. participant’s country. (3) Understanding methods of planning and implementing agricultural census and Ministry of Agriculture, etc.). sample survey, and possible to make the basic survey plan such as a prototype of questionnaires along (2) Experience in the relevant field: with more with the country’s situation. (4) Understanding utilization of latest technologies to be able to than 5 years of experience working in the introduce statistical surveys, and then possible to explain the possibility to apply them taking into central governmental agencies or other related account of efficiency and cost effectiveness. -

Group & Region Focus

【Online】 Knowledge Co-Creation Program (Group & Region Focus) GENERAL INFORMATION ON Strategic Management and Marketing for Sustainable Local Industry Development (B) 課題別研修「戦略的マネジメント・マーケティング による持続的地場産業振興(B)」 JFY 2021 NO. 202006509J001 Online Program Period: From Nov 2 to Nov 19, 2021 This information pertains to one of the JICA Knowledge Co-Creation Program (Group & Region Focus) of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which shall be implemented as part of the Official Development Assistance of the Government of Japan based on the bilateral agreement between both Governments. ‘JICA Knowledge Co-Creation Program (KCCP)’ as a New Start In the Development Cooperation Charter which was released from the Japanese Cabinet on February 2015, it is clearly pointed out that “In its development cooperation, Japan has maintained the spirit of jointly creating things that suit partner countries while respecting ownership, intentions and intrinsic characteristics of the country concerned based on a field-oriented approach through dialogue and collaboration. It has also maintained the approach of building reciprocal relationships with developing countries in which both sides learn from each other and grow and develop together.” We believe that this ‘Knowledge Co-Creation Program’ will serve as a center of mutual learning process. 1/18 I. Concept Background The number of disasters such as massive floods, wildfires, and draughts is dramatically increasing. Due to human-induced climate change, agriculture and the local economy are affected adverse effects ever before. All United Nations Member States adopted the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in 2015. However, we have not taken effective countermeasures yet. To achieve SDGs, it is indispensable to accelerate the transformation from "business as usual" to the new business models, obtaining economic profits while achieving social benefits. -

Finalre Agribus

Report of the Expert Consultation on Agribusiness Statistics Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, Thailand, 11 - 14 September 2001 Expert Consultation on Agricultural Statistics, 11-14 September 2001 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its territories or boundaries. Senior Statistician FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Maliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Atit Road Bangkok, 10200 Thailand ii Expert Consultation on Agricultural Statistics, 11-14 September 2001 Report of the Expert Consultation on Agribusiness Statistics Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, Thailand, 11 - 14 September 2001 iii Expert Consultation on Agricultural Statistics, 11-14 September 2001 Contents Opening Session 1 Election of Officers 2 Adoption of the Agenda and Timetable 2 Satellite Accounts for Agribusiness 2 Agribusiness Focus in Improving Food and Agricultural Statistics 3 Harnessing Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Facilities to Promote a User-responsive Agribusiness Statistics and Information System 4 Promoting Sustained Agricultural Sector Development through Demand-Driven Agricultural Statistics and Information Systems -

Hawaii's Crop Parade

HAWAII'S CROP PARADE A Review of Useful Products Derived fro m the Soil in the Hawaiian Islands, Past and Present By DAVID LIVINGSTON CRAWFORD ADVERTISER PUBLISHI~(i Co., Vl'D. HONOLULU" H'AWAII, U. S. A. 1937 HAWAII'S CROP PARADE COPYRIGHT,1937 BY THE ADVERTISER PUBLISHING CO•• LTD. PRINTED IN UNITED STATES OF AMERiCA BY ADVERTISER PUBLISHING CO., LTD. HONOLULU, HAWAII Table of Contents Pages gricultural Prospecting (A Preface) -------------___ 9 - 12 Acknowledgments ---------------------------------------------_______ 13 Historical Outline of Agriculture in the Hawaiian Islands --------------------------------- IS - 32 Hawaii s Crop Parade ------------------------------------- 33-289 Index of ientific ames______________________________________ 29 1 Inde., General ------------------------------------------------------__ 293 Agricultural Prospecting Back of the wealth-producing mine is the prospector, that lone figure trudging mountain and desert, sampling here, there and everywhere, always hopeful that the next thrust of his pick will open a bonanza. Back of our great agricultural industries, also, there is a long story of prospecting: the lone farmer trying many new crops, the pioneer company exploring the possibili ties in new products and untried land areas, the investiga tor and experimenter seeking the best that science can make possible for industrial development. The finding of a' good crop plant or animal and the subsequent establishment of a profitable industry there upon does not bring an end to this quest, for always there is the lure of the frontier, the creative margin, where the prospector continues his search for something new and better. The value of this prospecting service does not lie in the possibility that an established industry may be displaced by one that is new and more profitable; the greatest value is the strengthening and stabilizing of the economic struc ture of a state or a nation by the increased diversification in agricultural industries which results from the pros pector's discoveries.