Chapter 4: Topography of the Midwestern US

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATURAL RESOURCES (Updated Excerpt from Jo Daviess Comprehensive Plan Baseline Data)

ATTACHMENT F: NATURAL RESOURCES (Updated excerpt from Jo Daviess Comprehensive Plan Baseline Data) The natural resources in Jo Daviess County are unique relative to the rest of the state and much of the mid-west because the county is part of the Wisconsin Driftless Region bypassed by continental glaciers of the Ice Age. This region covers parts of southern Minnesota and Wisconsin, Northwestern Illinois and Northeastern Iowa. Glaciated areas were leveled, strewn with glacial debris or "drift" and dotted with lakes and ponds. The driftless areas, on the other hand, have bedrock close to the surface into which deep valleys have been carved by millions of years of weather and erosion. In Jo Daviess County, streams are numerous and the only two lakes are man-made. The relief from the higher ridges to the valley floors is typically 300 feet or more creating a rugged and scenic landscape. Ecosystems can be found in this landscape that are older than those found in glaciated areas. Geology The topography of Jo Daviess County is characterized by rugged relief unique to most of Illinois. Our county, located in the far northwestern corner of the state, is in an area spared by the major glaciations of the last two million years. It is, accordingly, called the "Driftless Area" by geologists, the term "drift" referring to material deposited by glacial activity. The visible landscape that we see today began during the Paleozoic Era (570 to 245 million years ago) when shallow seas repeatedly inundated the interior of the continent. Shells of marine animals, along with muds, silts and sands from eroding highlands, were periodically deposited in those sea bottoms. -

Encounters with the Early Highpointers by Charles

SOME CLOSE (AND NOT SO CLOSE) ENCOUNTERS WITH THE EARLY HIGHPOINTERS BY CHARLES FERIS Many stories can be told of how we got our first inspiration to pursue this hobby of ours, this highpointing. We’ve been inspired in a hundred ways; mine arose during a period of boredom, while in college. Seeking something other than study, I took out a Rand McNally road atlas, and looked at a map of my native state of Illinois, noting the little red dot in the northwest corner of the state. Wow, something neat to do. So while the other kids were off to Florida, off to Charles Mound I went during spring break 1961. Then it hit me; I had already done Mt. Whitney the year before, so why not do all the states. Now I was really excited. The next few years saw me collecting 13 more highpoints in the Midwest and southeast. I went my merry way, never realizing that others might be crazy enough to be pursuing the very same project. At this point I was not aware of the tiny fraternity of early highpointers who were already years before me. I had no idea of the remarkable people I was about to meet. Then in August 1965 a Sierra Club friend of mine in Chicago told me about C. Rowland Stebbins. I had found a kindred soul, one who had already completed the 48. I phoned him immediately. Soon my wife and I were off on the four hour drive to Lansing, Michigan. We arrived to an expansive mansion on Moore’s River Drive atop a bluff overlooking the Grand River. -

Climbing America's

batical leave in Scandinavia, I finally reached the 5895m summit of Africa’s high- est mountain. In 1986, the year after I climbed Kilimanjaro, Dick Bass, Frank Wells, and Rick Ridgeway published Seven Summits, an account of Bass and Wells’ attempt to climb the highest peak on each of the world’s seven continents. I bought their book and devoured it. Inspired by it, I devised my own climbing goal—to climb at least ‘Three-and-a-Half Summits’: namely, at least three of the six highest of the Seven Summits plus Australia’s Mt Kosciuszko, which is a mere 2228m above sea level (i.e., less than half the height of Antarctica’s Vinson Massif, the sixth-lowest of the Seven Summits), and Kosciuszko can therefore, as a Kiwi I quipped, really only be regarded as a half-summit. I made reasonably quick progress towards achieving my goal. In August 1994, I climbed Russia’s Mt Elbrus, 5642m, the highest mountain in Europe. In December the same year, I summited 6962m-high Cerro Aconcagua in Argentina, the highest mountain in South America (which I like to tell people is ‘the highest mountain in the world outside Asia,’ and then hope their geography is so weak that they don’t realise how huge an exclusion clause those two words, ‘outside Asia’, are). I then decided to have a crack at climbing Denali, and on 6 July 1997 stood proudly on the 6194m-high summit of North America’s high- est peak and held up a t-shirt from Victoria University (which is where I taught political science for many years). -

Society Officers

Spring “The challenge goes on. There are other lands and rivers, other wilderness areas, to save and to share with all. March 2019 I challenge you to step forward to protect and care for the wild places you love best.” - Dr. Neil Compton Introducing Emily Roberts by David Peterson, Ozark Society President Please join me in welcoming Emily Foundation/Pioneer Forest in Salem, Roberts to the Ozark Society team! Mo. She has experience most Emily will be working on book, map, recently as a fire a biological science and other material sales for us and technician in the botany program at you can contact her at the Mt. Hood National Forest in [email protected]. Here is Dufur, Oregon; as a field technician some information about Emily. She for the Romance Christmas Tree has a Bachelor of Science degree in Farm in Romance, Arkansas; and as environmental science, with a an AmeriCorps member at the biology concentration, and is a Salmon-Challis Forest Training graduate of the Norbert O. Schedler Center in Challis, Idaho. her Honors College at UCA. Roberts was background. a crew member for the L-A-D Buffalo River Handbook 2nd Edition by Ken Smith by Janet Parsch, Ozark Society Foundation Chair Ken Smith has done it again. The description of the new 28-mile 150 miles of hiking trails. The second edition of his wonderfully segment of the Buffalo River Trail / Handbook is a comprehensive successful first edition of Buffalo River Ozark Highlands Trail from U.S. reference book for the history and Handbook is available for purchase. -

The New York Public Library Amazing US Geography

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY AMAZING U.S. GEOGRAPHY A Book of Answers for Kids Andrea Sutcliffe John Wiley & Sons, Inc. c01.qxd 12/21/01 1:17 PM Page 4 fm.qxd 1/29/02 1:30 PM Page i THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY AMAZING U.S. GEOGRAPHY fm.qxd 1/29/02 1:30 PM Page ii fm.qxd 1/29/02 1:30 PM Page iii THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY AMAZING U.S. GEOGRAPHY A Book of Answers for Kids Andrea Sutcliffe John Wiley & Sons, Inc. fcopyebk.qxd 2/27/02 10:10 AM Page iv Copyright ©2001 by The New York Public Library and The Stonesong Press, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. All maps prepared by Netmaps, S.A. Photo, p.107; courtesy of Andrea Sutcliffe. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permission Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158-0012, (212) 850-6011, fax (212) 850-6008, email: [email protected]. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. -

Guide to the Geology of the Galena Area

5 (^$UiAA>*>M C 3 Guide to the Geology of the Galena Area Jo Daviess County, Illinois Lafayette County, Wisconsin David L. Reinertsen Field Trip Guidebook 1992B May 16, 1992 Department of Energy and Natural Resources ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY LIBRARY. Cover photos by D. L. Reinertsen Clockwise from upper left: Silurian dolomite cap on Scales Mound, early crevice mine south of Galena near the Mississippi River, and downtown Galena as viewed from the old Galena High School. Geological Science Field Trips The Educational Extension Unit of the Illinois State Geological Survey (ISGS) conducts four free tours each year to acquaint the public with the rocks, mineral resources, and landscapes of various regions of the state and the geological processes that have led to their origin. Each trip is an all-day excursion through one or more Illinois counties. Frequent stops are made to explore interesting phenomena, explain the processes that shape our environment, discuss principles of earth science, and collect rocks and fossils. People of all ages and interests are welcome. The trips are especially helpful to teachers who prepare earth science units. Grade school students are welcome, but each must be accompanied by a parent or guardian. High school science classes should be supervised by at least one adult for each ten students. A list of guidebooks of earlier field trips for planning class tours and private outings may be obtained by contacting the Educational Extension Unit, Illinois State Geological Survey, Natural Resources Building, 615 East Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820. Telephone: (217) 244- 2407 or 333-7372. -

Final-Draft-Revied-1-17-2020-Copy

Final Review Draft Revised 1/17/2020 Revisions are shown in red L’Anse Township, MI MASTER PLAN Update 2019 L’Anse Township Master Plan Acknowledgements L’Anse Township Planning Commission Roy Kemppainen, Chair Dan Robillard, Secreatary Joan Bugni Craig Kent Joanne Pennock Buddy Sweeney Mike Roberts L’Anse Township Board Peter Magaraggia, Supervisor Kristin Kahler, Clerk Kristine Rice, Treasurer Shelley Lloyd, Trustee Buddy Sweeney, Trustee Consultant: We also wish to thank the many citizens who attended meetings, the Open House Event, and who provided input on the development of this Master Plan! Cover photo: 2nd Sand Beach by Jeffery Loman Patrick Coleman, AICP Acknowledgements Page 1 L’Anse Township Master Plan Table of Contents Page Acknowledgements 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: Township Profile 10 Chapter 3: Housing 39 Chapter 4: Infrastructure and Community Facilities 44 Chapter 5: Land Use 53 Chapter 6: Transportation 69 Chapter 7: Economic Development 80 Chapter 8: Action Plan 86 Table of Contents Page 2 L’Anse Township Master Plan Chapter 1: Introduction This plan was undertaken to help the citizens of L’Anse Township make informed decisions and set priorities and goals to achieve a sustainable future. The plan contains recommendations and action strategies to assist the Township to organize efforts and resources for maximum potential. The plan will serve as a guide for future decisions about growth management and development, land-use regulation, and infrastructure. Authority and Purpose The purpose of the Master Plan is to guide the future of the Township and help the community develop sustainably through a realistic and well thought out approach. -

Driftless Area - Wikipedia Visited 02/19/2020

2/19/2020 Driftless Area - Wikipedia Visited 02/19/2020 Driftless Area The Driftless Area is a region in southwestern Wisconsin, southeastern Minnesota, northeastern Iowa, and the extreme northwestern corner of Illinois, of the American Midwest. The region escaped the flattening effects of glaciation during the last ice age and is consequently characterized by steep, forested ridges, deeply carved river valleys, and karst geology characterized by spring-fed waterfalls and cold-water trout streams. Ecologically, the Driftless Area's flora and fauna are more closely related to those of the Great Lakes region and New England than those of the broader Midwest and central Plains regions. Colloquially, the term includes the incised Paleozoic Plateau of southeastern Minnesota and northeastern Relief map showing primarily the [1] Iowa. The region includes elevations ranging from 603 to Minnesota part of the Driftless Area. The 1,719 feet (184 to 524 m) at Blue Mound State Park and wide diagonal river is the Upper Mississippi covers 24,000 square miles (62,200 km2).[2] The rugged River. In this area, it forms the boundary terrain is due both to the lack of glacial deposits, or drift, between Minnesota and Wisconsin. The rivers entering the Mississippi from the and to the incision of the upper Mississippi River and its west are, from the bottom up, the Upper tributaries into bedrock. Iowa, Root, Whitewater, Zumbro, and Cannon Rivers. A small portion of the An alternative, less restrictive definition of the Driftless upper reaches of the Turkey River are Area includes the sand Plains region northeast of visible west of the Upper Iowa. -

Woody Connette, Climbing to the Top in 50 States

REPORTERrd charlotterotary.org 704.375.6816 1850 East 3 St, Ste 220, Charlotte NC 28204 January 28, 2020 We meet on Tuesday at 12:30 pm at Fairfield Inn & Suites – Charlotte Uptown, 201 South McDowell St, Charlotte NC 28202 WOODY CONNETTE 2019 - 2020 Board Members Climbing to the Top in 50 States President John W. Lassiter Today we had the pleasure of hearing from Edward Pres Elect Jerry Coughter “Woody” Connette. Woody is a highly regarded Past Pres Mike Hawley Charlotte litigation attorney. It wasn’t until he Secretary Sandy Osborne Treasurer Phil Volponi reached 61 years of age that he decided his passionate weekend goal would be to climb the Directors 2019-2020 highest peaks in all 50 states. To him that sounded Cheryl Banks very doable; he had already done three so only William Bradley forty-seven to go! Dena Diorio Carla DuPuy Bill Loftin, Jr. Woody began his remarks thanking Rotary for Clyde Robinson being the catalyst and founder of Easter Seals in Rudy Rudisill Mecklenburg County 100 years ago. Woody has become very involved with Easter Seals, every year witnessing the more than Directors 2019-2021 Colleen Brannan 4,000 Charlotte area served and 19,000 statewide. Stuart Hair Stephanie Hinrichs When, how and why did Woody decide to climb the 50 highest peaks in all 50 Chris Kemper states, an accomplishment he completed with his wife at Mauna Kea in Hawaii? Chad Lloyd You wouldn’t think that Woody’s upbringing would lead to this ambitious goal. Alexandra Myrick Edwin Peacock, III Woody grew up far from the mountains in Wilmington in the 1950’s, a time when the population of Wilmington was shrinking. -

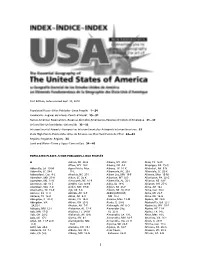

Download Index

First Edition, Index revised Sept. 23, 2010 Populated Places~Sitios Poblados~Lieux Peuplés 1—24 Landmarks~Lugares de Interés~Points d’Intérêt 25—31 Native American Reservations~Reservas de Indios Americanos~Réserves d’Indiens d’Améreque 31—32 Universities~Universidades~Universités 32—33 Intercontinental Airports~Aeropuertos Intercontinentales~Aéroports Intercontinentaux 33 State High Points~Puntos Mas Altos de Estados~Les Plus Haut Points de l’État 33—34 Regions~Regiones~Régions 34 Land and Water~Tierra y Agua~Terre et Eau 34—40 POPULATED PLACES~SITIOS POBLADOS~LIEUX PEUPLÉS A Adrian, MI 23-G Albany, NY 29-F Alice, TX 16-N Afton, WY 10-F Albany, OR 4-E Aliquippa, PA 25-G Abbeville, LA 19-M Agua Prieta, Mex Albany, TX 16-K Allakaket, AK 9-N Abbeville, SC 24-J 11-L Albemarle, NC 25-J Allendale, SC 25-K Abbotsford, Can 4-C Ahoskie, NC 27-I Albert Lea, MN 19-F Allende, Mex 15-M Aberdeen, MD 27-H Aiken, SC 25-K Alberton, MT 8-D Allentown, PA 28-G Aberdeen, MS 21-K Ainsworth, NE 16-F Albertville, AL 22-J Alliance, NE 14-F Aberdeen, SD 16-E Airdrie, Can 8,9-B Albia, IA 19-G Alliance, OH 25-G Aberdeen, WA 4-D Aitkin, MN 19-D Albion, MI 23-F Alma, AR 18-J Abernathy, TX 15-K Ajo, AZ 9-K Albion, NE 16,17-G Alma, Can 30-C Abilene, KS 17-H Akhiok, AK 9-P ALBUQUERQUE, Alma, MI 23-F Abilene, TX 16-K Akiak, AK 8-O NM 12-J Alma, NE 16-G Abingdon, IL 20-G Akron, CO 14-G Aldama, Mex 13-M Alpena, MI 24-E Abingdon, VA Akron, OH 25-G Aledo, IL 20-G Alpharetta, GA 23-J 24,25-I Akutan, AK 7-P Aleknagik, AK 8-O Alpine Jct, WY 10-F Abiquiu, NM 12-I Alabaster, -

Geography and Environment

Section 6 Geography and Environment This section presents a variety of informa- In a joint project with the U.S. Census tion on the physical environment of the Bureau, during the 1980s, the USGS pro- United States, starting with basic area vided the basic information on geo- measurement data and ending with cli- graphic features for input into a national matic data for selected weather stations geographic and cartographic database around the country. The subjects covered prepared by the Census Bureau, called between those points are mostly con- TIGER® database. Since then, using a vari- cerned with environmental trends but ety of sources, the Census Bureau has include related subjects such as land use, updated these features and their related water consumption, air pollutant emis- attributes (names, descriptions, etc.) and sions, toxic releases, oil spills, hazardous inserted current information on the waste sites, municipal waste and recy- boundaries, names, and codes of legal cling, threatened and endangered wildlife, and statistical geographic entities; very and the environmental industry. few of these updates added aerial water features. Maps prepared by the Census The information in this section is selected Bureau using the TIGER® database show from a wide range of federal agencies the names and boundaries of entities and that compile the data for various adminis- are available on a current basis. trative or regulatory purposes, such as the Environmental Protection Agency An inventory of the nation’s land (EPA), U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), resources by type of use/cover was con- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Admin- ducted by the National Resources Inven- istration (NOAA), Natural Resources Con- tory Conservation Services (NRCS) every 5 servation Service (NRCS), and General Ser- years beginning in 1977 through 1997. -

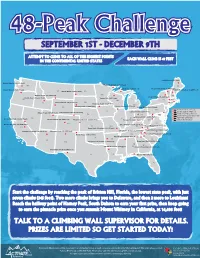

PRINT 48-Peak Challenge

48-Peak Challenge SEPTEMBER 1ST - DECEMBER 9TH ATTEMPT TO CLIMB TO ALL OF THE HIGHEST POINTS EACH WALL CLIMB IS 47 FEET IN THE CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES Katahdin (5,268 feet) Mount Rainier (14,411 feet) WA Eagle Mountain (2,301 feet) ME Mount Arvon (1,978 feet) Mount Mansfield (4,393 feet) Mount Hood (11,239 feet) Mount Washington (6,288 feet) MT White Butte (3,506 feet) ND VT MN Granite Peak (12,799 feet) NH Mount Marcy (5,344 feet) Borah Peak (12,662 feet) OR Timms Hill (1,951 feet) WI NY MA ID Gannett Peak (13,804 feet) SD CT Hawkeye Point (1,670 feet) RI MI Charles Mount (1,235 feet) WY Harney Peak (7,242 feet) Mount Davis (3,213 feet) PA CT: Mount Frissell (2,372 feet) IA NJ DE: Ebright Azimuth (442 feet) Panorama Point (5,426 feet) Campbell Hill (1,549 feet) Kings Peak (13,528 feet) MA: Mount Greylock (3,487 feet) NE OH MD DE MD: Backbone Mountain (3360 feet) Spruce Knob (4,861 feet) NV IN NJ: High Point (1,803 feet) Boundary Peak (13,140 feet) IL Mount Elbert (14,433 feet) Mount Sunflower (4,039 feet) Hoosier Hill (1,257 feet) WV RI: Jerimoth Hill (812 feet) UT CO VA Mount Whitney (14,498 feet) Black Mountain (4,139 feet) KS Mount Rogers (5,729 feet) CA MO KY Taum Sauk Mountain (1,772 feet) Mount Mitchell (6,684 feet) Humphreys Peak (12,633 feet) Wheeler Peak (12,633 feet) Clingmans Dome (6,643 feet) NC Sassafras Mountain (3,554 feet) Black Mesa (4,973 feet) TN Woodall Mountain (806 Feet) OK AR SC AZ NM Magazine Mountain (2,753 feet) Brasstown Bald (4,784 feet) GA AL Driskill Mountain (535MS feet) Cheaha Mountain (2,405 feet) Guadalupe Peak (8,749 feet) TX LA Britton Hill (345 feet) FL Start the challenge by reaching the peak of Britton Hill, Florida, the lowest state peak, with just seven climbs (345 feet).