The Scheduled Castes of Colonial Bengal in Historiographical Perspective1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAAC NBU SSR 2015 Vol II

ENLIGHTENMENT TO PERFECTION SELF-STUDY REPORT for submission to the National Assessment & Accreditation Council VOLUME II Departmental Profile (Faculty Council for PG Studies in Arts, Commerce & Law) DECEMBER 2015 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL [www.nbu.ac.in] Raja Rammohunpur, Dist. Darjeeling TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number Departments 1. Bengali 1 2. Centre for Himalayan Studies 45 3. Commerce 59 4. Lifelong Learning & Extension 82 5. Economics 89 6. English 121 7. Hindi 132 8. History 137 9. Law 164 10. Library & Information Science 182 11. Management 192 12. Mass Communication 210 13. Nepali 218 14. Philosophy 226 15. Political Science 244 16. Sociology 256 Research & Study Centres 17. Himalayan Studies (Research Unit placed under CHS) 18. Women’s Studies 266 19. Studies in Local languages & Culture 275 20. Buddhist Studies (Placed under the Department of Philosophy) 21. Nehru Studies (Placed under the Department of Political Science) 22. Development Studies (Placed under the Department of Political Science) _____________________________________________________________________University of North Bengal 1. Name of the Department : Bengali 2. Year of establishment : 1965 3. Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the University? Department is the Faculty of the University 4. Name of the programmes offered (UG, PG, M. Phil, Ph.D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc., D.Litt., etc.) : (i) PG, (ii) M. Phil., (iii) Ph. D., (iv) D. Litt. 5. Interdisciplinary programmes and departments involved : NIL 6. Course in collaboration with other universities, industries, foreign institution, etc. : NIL 7. Details of programmes discontinued, if any, with reasons 2 Years M.Phil.Course (including Methadology in Syllabus) started in 2007 (Session -2007-09), it continued upto 2008 (Session - 2008-10); But it is discontinued from 2009 for UGC Instruction, 2009 regarding Ph. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

The Most Important Current Affairs May 2020

The Monthly Hindu Review|Current Affairs|May 2020 The Most Important Current Affairs May 2020 Prime Minister announces Economic Package ⚫ The CGTSME will provide partial credit guarantee of Rs 20 Lakh Crore support to Banks in order to benefit the stressed MSMEs. Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi addressed his countrymen and announced an Economic Package of Rs ⚫ The promoters of the MSME will be given debt by 20 Lakh crore, giving stress on land, labour, liquidity banks, which would be infused by the promoter as and law. PM stressed on the local products and urged his equity in the unit. countrymen to be “Vocal About Local”. Prime Minister also mentioned 5-Pillars to make India self-reliant. These 3. For MSME having potential and which are viable: 5 pillars are: ⚫ A fund of fund has been created to infuse equity of 1. Economy: An economy that brings quantum jump worth Rs 50,000 crore in the MSME. along with incremental change. ⚫ Fund of Fund with corpus of Rs 10,000 crores would 2. Infrastructure: An infrastructure that becomes the be set up to provide equity funding to MSMEs with symbol of modern India. growth potential and viability. 3. System: A system which will be based on technology. ⚫ This FoF would be operated via a mother fund 4. Demography: A vibrant demography which would be including some daughter funds. the strength as well as the source of energy for self ⚫ FoF is expected to benefit MSMEs by expanding size reliant India. along with their capacity. 5. Demand: To improve demand and supply chain in India to enhance the Indian economy. -

Sri Aurobindo

NACIONAL BIOGRAPHY SERIES SRI AUROBINDO NAVAJATA NATIONAL BOOK TRUST, INDIA. Nueva Delhi. Primera edición: Marzo: 1.972 Edición revisada: Diciembre: 1.976 © Navajata, 1972 PUBLICADA POR EL DIRECTOR, NATIONAL BOOK TRUST, INDIA, A – 5 GREEN PARK, NUEVA DELHI-16 E IMPRESO EN REKHA PRINTERS PVT. LTD, NUEVA DELHI 110020 Este libro está dedicado a la Madre. PREFACIO Miles de personas, al visitar el Sri Aurobindo Ashram en Pondicherry, tienen la suerte de respirar su atmósfera impregnada de paz, todavía más acusada en el edificio principal. Aquí, en el patio, se halla el samadhi de Sri Aurobindo y de la Madre. Un enorme árbol, cuyo término botánico es Peltophorum ferrugineum, de aproximadamente treinta y cinco pies de altura y al que la Madre llamaba The Service Tree, forma un dosel natural sobre el depósito. En torno a éste los sadhakas, e igualmente los visitantes, meditan: algunos aspiran a abrirse a la Consciencia Divina; otros, concentrados en realizar una total transformación supramental; mientras que los hay también que colocan repetidamente sus penas y dificultades seculares a los pies de Sri Aurobindo, e imploran su ayuda. No es sorprendente que todos reciban asistencia según su disposición receptiva, porque la Madre dijo: ‘Sri Aurobindo no nos ha abandonado; Sri Aurobindo está aquí, tan vivo y tan presente como lo ha estado siempre, y nos ha dejado para realizar su labor con toda la sinceridad, con todo el entusiasmo y con toda la concentración necesarios.’ Y también: ‘Señor, esta mañana me has dado la seguridad de que permanecerías con nosotros hasta que tu obra estuviese acabada, no sólo como consciencia sino también como Presencia dinámica en acción. -

SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements

2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 7 ‘My kind of theatre is for the people’ KUMAR ROY 37 ‘And through the poetry we found a new direction’ SHYAMAL GHO S H 59 Minority Culture, Universal Voice RUDRAPRA S AD SEN G UPTA 81 ‘A different kind of confidence and strength’ Editor AS IT MU K HERJEE Anjum Katyal Editorial Consultant Samik Bandyopadhyay 99 Assistants Falling in Love with Theatre Paramita Banerjee ARUN MU K HERJEE Sumita Banerjee Sudeshna Banerjee Sunandini Banerjee 109 Padmini Ray Chaudhury ‘Your own language, your own style’ Vikram Iyengar BI B HA S H CHA K RA B ORTY Design Sunandini Banerjee 149 Photograph used on cover © Nemai Ghosh ‘That tiny cube of space’ MANOJ MITRA 175 ‘A theatre idiom of my own’ AS IT BO S E 197 The Totality of Theatre NIL K ANTHA SEN G UPTA 223 Conversations Published by Naveen Kishore 232 for The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Appendix I 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 Notes on Classic Playtexts Printed at Laurens & Co. 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 234 Appendix II Notes on major Bengali Productions 1944 –-2000 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements Most of the material collected for documentation in this issue of STQ, had already been gathered when work for STQ 27/28 was in progress. We would like to acknowledge with deep gratitude the cooperation we have received from all the theatre directors featured in this issue. We would especially like to thank Shyamal Ghosh and Nilkantha Sengupta for providing a very interesting and rare set of photographs; Mohit Chattopadhyay, Bibhash Chakraborty and Asit Bose for patiently answering our queries; Alok Deb of Pratikriti for providing us the production details of Kenaram Becharam; Abhijit Kar Gupta of Chokh, who has readily answered/ provided the correct sources. -

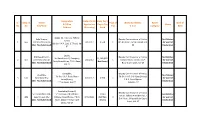

Sl. No Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application

Designation Date of First Basic Pay / Sl. Comp. Sl. Name Type of Name & Address Roster Date of & Office Application Pay in Pay Status No No S/D/W/O Flat D.D.O. Category Birth Address (Receving) Band Sepoy-32, H.Q. Coy. Kolkata Kaila Sherpa, Deputy Commissioner of Police, Not Allotted Police, 1 666 Late Kancha Sherpa 2/1/2012 8,570 C 8th Bn.K.A.P. 29/1 B.T.Road, Kol- for want of 8th Bn. K.A.P. 29/1 B.T.Road, Kol- (Dec. Not Submitted) 02 Dealaration 02 Sepoy, Mir Rejaul Karim, Deputy Commissioner of Police, Not Allotted 3rd Battalian H.Q. Company, 12,240 (G.P. 2 667 Late Mir Ershad Ali 2/1/2012 C Kolkata Police, 3rd Bn. K.A.P. for want of Body Guard Lines, 7 D.H. Road, Not Given) (Dec. Not Submitted) Body Guard Lines, Kol-27 Dealaration Kol-27 Constable, Deputy Commissioner of Police, Utpal Roy, Not Allotted 7th Bn. K.A.P. Body Guard 7th Bn. K.A.P. B.G. Lines,(Alipur) 3 670 Banchhalal Roy 4/1/2012 8,920 C for want of Lines(Alipur), 7, D.H. Road Alipore, (Dec. Not Submitted) Dealaration 7 D.H. Road, Kol-27 Kolkata - 27 Constable (Group-C) Deputy Commissioner of Police, Sri Chakradhari Mal, 'E' Company 7th Battalion 12240 Not Allotted 7th Bn. Kolkata Armed Police, 7 4 689 Late Nilratan Mal Kolkata Armed Police, 7 D.H. 24/1/2012 (G.P.Not C for want of D.H. Road, (Alipore Body Guard (Dec. -

Annual Report 17-18 Full Chap Final Tracing.Pmd

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2017-2018 Santiniketan 2018 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Dee®ee³e& MeebefleefveJesÀleve - 731235 Þeer vejsbê ceesoer efkeMkeYeejleer SANTINIKETAN - 731235 efpe.keerjYetce, heefM®ece yebieeue, Yeejle ACHARYA (CHANCELLOR) VISVA-BHARATI DIST. BIRBHUM, WEST BENGAL, INDIA SHRI NARENDRA MODI (Established by the Parliament of India under heÀesve Tel: +91-3463-262 451/261 531 Visva-Bharati Act XXIX of 1951 hewÀJeÌme Fax: +91-3463-262 672 Ghee®ee³e& Vide Notification No. : 40-5/50 G.3 Dt. 14 May, 1951) F&-cesue E-mail : [email protected] Òees. meyegpeJeÀefue mesve Website: www.visva-bharati.ac.in UPACHARYA (VICE-CHANCELLOR) (Offig.) mebmLeeheJeÀ PROF. SABUJKOLI SEN jkeervêveeLe þeJegÀj FOUNDED BY RABINDRANATH TAGORE FOREWORD meb./No._________________ efoveebJeÀ/Date._________________ For Rabindranath Tagore, the University was the most vibrant part of a nation’s cultural and educational life. In his desire to fashion a holistic self that was culturally, ecologically and ethically enriched, he saw Visva-Bharati as a utopia of the cross cultural encounter. During the course of the last year, the Visva-Bharati fraternity has been relentlessly pursuing this dream. The recent convocation, where the Chancellor Shri Narendra Modi graced the occasion has energized the Univer- sity community, especially because this was the Acharya’s visit after 10 years. -

Annual Report 2015-2016

VISVA-BHARATI Annual Report 2015-2016 Santiniketan 2016 YATRA VISVAM BHAVATYEKANIDAM (Where the World makes its home in a single nest) “ Visva-Bharati represents India where she has her wealth of mind which is for all. Visva-Bharati acknowledges India's obligation to offer to others the hospitality of her best culture and India's right to accept from others their best ” -Rabindranath Tagore Contents Chapter I ................................................................i-v Department of Biotechnology...............................147 From Bharmacharyashrama to Visva-Bharati...............i Centre for Mathematics Education........................152 Institutional Structure Today.....................................ii Intergrated Science Education & Research Centre.153 Socially Relevant Research and Other Activities .....iii Finance ................................................................... v Kala Bhavana.................................................157 -175 Administrative Staff Composition ............................vi Department of Design............................................159 University At a Glance................................................vi Department of Sculpture..........................................162 Student Composition ................................................vi Department of Painting..........................................165 Teaching Staff Composition.....................................vi Department of Graphic Art....................................170 Department of History of Art..................................172 -

Calcutta City, Part III, Vol-VI, West Bengal

PCC.I03 -f66- CENSUS OF INDIA 1951 VOLUME VI-PART III CALCUTTA CITY A. MITRA of the Indian Civil Service, Superintendent of Census Operations and Joint Development Commissioner, West Bengal PuBLl:SBEB BY Tl'IE MANAGER OF PuBLICATIONS, DELHl:. PlUNTED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS. CALCUTTA. INDIA ~954. price; Rs. 17-1~ or ~7sh. 6<l. THE CENSUS PUBLICATIONS THE CENSUS PUBLICATIONS for West Bengal, Sikkim and Chandernagore will ~onsist of the foltowing volumes. An volumes will be of uniform size, demy quarto 8f" x Iii Part IA-General'Report by A. Mitra, containing the first five chapters of tlie .Report ilL addition· to'(l, Preface, an Introduction, and a Bibliography. 587 pages. Part IB-Vital Statistics, West Bengal, 1941-50 by A. Mitra and P. G_ \.,.,nOUUQury, comamlUg a J:''f-elace. 60 tables, and several appendices. 75 pages. • Part IC-General Report by A. Mitra containing the Subsidiary tables of 1951 a1id~ the ·sixth 'chapt~r of the Report and a note on a Fertility Inquiry conducted in 1950. Some reprints and 'Special notes. A report on the natural resources, trades and industries of the State with two bibliographies by Chanchal Kumar Chatterjee and Kamal Majumdar. 517 pages. Part II-Union and State Census Tables of West Bengal, Sikkim and Chandernagore by A. Mitra. 535 pages. PaTt III-Report on Calcutta City by A. Mitra. (The present volume.) Part IV-Tables of the Calcutta Industrial Region by A. Mitra. 438 pages. Part V-Administrative Report of the Census Operations of West Bengal, Sikkim, Chandernagore and Calcutta City: Enumeration: by A. -

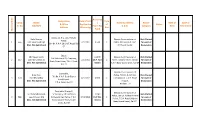

W Aitin G Sl No Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application

Basic Pay Designation Date of First Type Comp. Name / Name & Address Roster Date of Date of & Office Application of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O Pay in Pay D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Flat Band Waiting Sl No Sepoy-32, H.Q. Coy. Kolkata Kaila Sherpa, Deputy Commissioner of Not Allotted Police, 1 666 Late Kancha Sherpa 2/1/2012 8,570 C Police, 8th Bn.K.A.P. 29/1 for want of 8th Bn. K.A.P. 29/1 B.T.Road, Kol- (Dec. Not Submitted) B.T.Road, Kol-02 Dealaration 02 Sepoy, Mir Rejaul Karim, 12,240 Deputy Commissioner of Not Allotted 3rd Battalian H.Q. Company, 2 667 Late Mir Ershad Ali 2/1/2012 (G.P. Not C Police, Kolkata Police, 3rd Bn. for want of Body Guard Lines, 7 D.H. Road, (Dec. Not Submitted) Given) K.A.P. Body Guard Lines, Kol-27 Dealaration Kol-27 Deputy Commissioner of Constable, Utpal Roy, Police, 7th Bn. K.A.P. B.G. Not Allotted 7th Bn. K.A.P. Body Guard 3 670 Banchhalal Roy 4/1/2012 8,920 C Lines,(Alipur) 7, D.H. Road for want of Lines(Alipur), (Dec. Not Submitted) Alipore, Dealaration 7 D.H. Road, Kol-27 Kolkata - 27 Constable (Group-C) Deputy Commissioner of Sri Chakradhari Mal, 'E' Company 7th Battalion 12240 Not Allotted Police, 7th Bn. Kolkata Armed 4 689 Late Nilratan Mal Kolkata Armed Police, 7 D.H. 24/1/2012 (G.P.Not C for want of Police, 7 D.H. -

First Hexagonal Postage Stamps on Aldabra Giant Tortoise

Orissa Review shape, trigonal shape and hexagonal shape. Here we shall discuss the story of a tortoise named First Adwaita. We all know about the folk tales of tortoise who Hexagonal defeated the hare and won the race. Well, Adwaita was also a Postage winner. Before it died in the year 2006 in Alipore Stamps on Zoological Garden, Kolkata, Adwaita was perhaps the Aldabra Giant longest living animal in the world having lived for more than 250 centrally located octagonal Tortoise years. enclosure so that visitors could see this living wonder from a Nothing specific can safe distance. be told about its early life. It is Nrusingha Dash said that British sailors coming People lovingly called to India picked up some it Adwaita meaning the tortoises from the Aldabra matchless or the unique one as Islands in the Indian ocean on it was a living example of way to India. Legend has it that nature's mystery. It is supposed these were presented to Robert to have been born in 1750. It Generally we see the postage Clive (Governor General of was fed wheat bran, grams stamps of India in quadrilateral India) who was instrumental in soaked in water, small pieces shapes. In the post- firmly establishing the rule of the of carrots, sweet potatoes, Independence era Indian Postal British East India Company in beans, leafy vegetables, diced Department had issued only India especially after the Battle banana and rice mixed with two commemorative postage of Plassey (1757). Four such gram powder. The Aldabra stamps in trigonal shape on tortoises were brought to Giant Tortoise (Geochelone different occasions.