The Functional Diversity of Aurora Kinases: a Comprehensive Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title a New Centrosomal Protein Regulates Neurogenesis By

Title A new centrosomal protein regulates neurogenesis by microtubule organization Authors: Germán Camargo Ortega1-3†, Sven Falk1,2†, Pia A. Johansson1,2†, Elise Peyre4, Sanjeeb Kumar Sahu5, Loïc Broic4, Camino De Juan Romero6, Kalina Draganova1,2, Stanislav Vinopal7, Kaviya Chinnappa1‡, Anna Gavranovic1, Tugay Karakaya1, Juliane Merl-Pham8, Arie Geerlof9, Regina Feederle10,11, Wei Shao12,13, Song-Hai Shi12,13, Stefanie M. Hauck8, Frank Bradke7, Victor Borrell6, Vijay K. Tiwari§, Wieland B. Huttner14, Michaela Wilsch- Bräuninger14, Laurent Nguyen4 and Magdalena Götz1,2,11* Affiliations: 1. Institute of Stem Cell Research, Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 2. Physiological Genomics, Biomedical Center, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Germany. 3. Graduate School of Systemic Neurosciences, Biocenter, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Germany. 4. GIGA-Neurosciences, Molecular regulation of neurogenesis, University of Liège, Belgium 5. Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB), Mainz, Germany. 6. Instituto de Neurociencias, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas and Universidad Miguel Hernández, Sant Joan d’Alacant, Spain. 7. Laboratory for Axon Growth and Regeneration, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), Bonn, Germany. 8. Research Unit Protein Science, Helmholtz Centre Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 9. Protein Expression and Purification Facility, Institute of Structural Biology, Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 10. Institute for Diabetes and Obesity, Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility, Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany. 11. SYNERGY, Excellence Cluster of Systems Neurology, Biomedical Center, Ludwig- Maximilian University Munich, Germany. 12. Developmental Biology Program, Sloan Kettering Institute, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA 13. -

Bioinformatics Identi Cation of Prognostic Factors Associated With

Bioinformatics Identication of Prognostic Factors Associated with Breast Cancer Ying Wei Sichuan University https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8178-4705 Shipeng Zhang College of Pharmacy, North Sichuan Medical College Li Xiao West China School of Basic Medical Sciences and Forensic Medicine Jing Zou West China School of Basic Medical Sciences and Forensic Medicine Yingqing Fu West China School of Basic Medical Sciences and Forensic Medicine Yi Ye West China School of Basic Medical Sciences and Forensic Medicine Linchuan Liao ( [email protected] ) West China School of Basic Medical Sciences and Forensic Medicine https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3700-8471 Research Keywords: Breast cancer, Differentially expressed genes, miRNAs, Transcription factors, Bioinformatic analysis Posted Date: December 2nd, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-117477/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/23 Abstract Background: Breast cancer (BRCA) remains one of the most common forms of cancer and is the most prominent driver of cancer-related death among women. The mechanistic basis for BRCA, however, remains incompletely understood. In particular, the relationships between driver mutations and signaling pathways in BRCA are poorly characterized, making it dicult to identify reliable clinical biomarkers that can be employed in diagnostic, therapeutic, or prognostic contexts. Methods: First, we downloaded publically available BRCA datasets (GSE45827, GSE42568, and GSE61304) from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. We then compared gene expression proles between tumor and control tissues in these datasets using Venn diagrams and the GEO2R analytical tool. We further explore the functional relevance of BRCA-associated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) via functional and pathway enrichment analyses using the DAVID tool, and we then constructed a protein-protein interaction network incorporating DEGs of interest using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database. -

DNA Damage Activates a Spatially Distinct Late Cytoplasmic Cell-Cycle Checkpoint Network Controlled by MK2-Mediated RNA Stabilization

DNA Damage Activates a Spatially Distinct Late Cytoplasmic Cell-Cycle Checkpoint Network Controlled by MK2-Mediated RNA Stabilization The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Reinhardt, H. Christian, Pia Hasskamp, Ingolf Schmedding, Sandra Morandell, Marcel A.T.M. van Vugt, XiaoZhe Wang, Rune Linding, et al. “DNA Damage Activates a Spatially Distinct Late Cytoplasmic Cell-Cycle Checkpoint Network Controlled by MK2-Mediated RNA Stabilization.” Molecular Cell 40, no. 1 (October 2010): 34–49.© 2010 Elsevier Inc. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.018 Publisher Elsevier B.V. Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/85107 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. Molecular Cell Article DNA Damage Activates a Spatially Distinct Late Cytoplasmic Cell-Cycle Checkpoint Network Controlled by MK2-Mediated RNA Stabilization H. Christian Reinhardt,1,6,7,8 Pia Hasskamp,1,10,11 Ingolf Schmedding,1,10,11 Sandra Morandell,1 Marcel A.T.M. van Vugt,5 XiaoZhe Wang,9 Rune Linding,4 Shao-En Ong,2 David Weaver,9 Steven A. Carr,2 and Michael B. Yaffe1,2,3,* 1David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02132, USA 2Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02132, USA 3Center for Cell Decision Processes, -

The P53/P73 - P21cip1 Tumor Suppressor Axis Guards Against Chromosomal Instability by Restraining CDK1 in Human Cancer Cells

Oncogene (2021) 40:436–451 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-020-01524-4 ARTICLE The p53/p73 - p21CIP1 tumor suppressor axis guards against chromosomal instability by restraining CDK1 in human cancer cells 1 1 2 1 2 Ann-Kathrin Schmidt ● Karoline Pudelko ● Jan-Eric Boekenkamp ● Katharina Berger ● Maik Kschischo ● Holger Bastians 1 Received: 2 July 2020 / Revised: 2 October 2020 / Accepted: 13 October 2020 / Published online: 9 November 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. This article is published with open access Abstract Whole chromosome instability (W-CIN) is a hallmark of human cancer and contributes to the evolvement of aneuploidy. W-CIN can be induced by abnormally increased microtubule plus end assembly rates during mitosis leading to the generation of lagging chromosomes during anaphase as a major form of mitotic errors in human cancer cells. Here, we show that loss of the tumor suppressor genes TP53 and TP73 can trigger increased mitotic microtubule assembly rates, lagging chromosomes, and W-CIN. CDKN1A, encoding for the CDK inhibitor p21CIP1, represents a critical target gene of p53/p73. Loss of p21CIP1 unleashes CDK1 activity which causes W-CIN in otherwise chromosomally stable cancer cells. fi Vice versa 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: Consequently, induction of CDK1 is suf cient to induce abnormal microtubule assembly rates and W-CIN. , partial inhibition of CDK1 activity in chromosomally unstable cancer cells corrects abnormal microtubule behavior and suppresses W-CIN. Thus, our study shows that the p53/p73 - p21CIP1 tumor suppressor axis, whose loss is associated with W-CIN in human cancer, safeguards against chromosome missegregation and aneuploidy by preventing abnormally increased CDK1 activity. -

Expression Profiling of KLF4

Expression Profiling of KLF4 AJCR0000006 Supplemental Data Figure S1. Snapshot of enriched gene sets identified by GSEA in Klf4-null MEFs. Figure S2. Snapshot of enriched gene sets identified by GSEA in wild type MEFs. 98 Am J Cancer Res 2011;1(1):85-97 Table S1: Functional Annotation Clustering of Genes Up-Regulated in Klf4 -Null MEFs ILLUMINA_ID Gene Symbol Gene Name (Description) P -value Fold-Change Cell Cycle 8.00E-03 ILMN_1217331 Mcm6 MINICHROMOSOME MAINTENANCE DEFICIENT 6 40.36 ILMN_2723931 E2f6 E2F TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR 6 26.8 ILMN_2724570 Mapk12 MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 12 22.19 ILMN_1218470 Cdk2 CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE 2 9.32 ILMN_1234909 Tipin TIMELESS INTERACTING PROTEIN 5.3 ILMN_1212692 Mapk13 SAPK/ERK/KINASE 4 4.96 ILMN_2666690 Cul7 CULLIN 7 2.23 ILMN_2681776 Mapk6 MITOGEN ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 4 2.11 ILMN_2652909 Ddit3 DNA-DAMAGE INDUCIBLE TRANSCRIPT 3 2.07 ILMN_2742152 Gadd45a GROWTH ARREST AND DNA-DAMAGE-INDUCIBLE 45 ALPHA 1.92 ILMN_1212787 Pttg1 PITUITARY TUMOR-TRANSFORMING 1 1.8 ILMN_1216721 Cdk5 CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASE 5 1.78 ILMN_1227009 Gas2l1 GROWTH ARREST-SPECIFIC 2 LIKE 1 1.74 ILMN_2663009 Rassf5 RAS ASSOCIATION (RALGDS/AF-6) DOMAIN FAMILY 5 1.64 ILMN_1220454 Anapc13 ANAPHASE PROMOTING COMPLEX SUBUNIT 13 1.61 ILMN_1216213 Incenp INNER CENTROMERE PROTEIN 1.56 ILMN_1256301 Rcc2 REGULATOR OF CHROMOSOME CONDENSATION 2 1.53 Extracellular Matrix 5.80E-06 ILMN_2735184 Col18a1 PROCOLLAGEN, TYPE XVIII, ALPHA 1 51.5 ILMN_1223997 Crtap CARTILAGE ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 32.74 ILMN_2753809 Mmp3 MATRIX METALLOPEPTIDASE -

Supplementary Data

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA A cyclin D1-dependent transcriptional program predicts clinical outcome in mantle cell lymphoma Santiago Demajo et al. 1 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA INDEX Supplementary Methods p. 3 Supplementary References p. 8 Supplementary Tables (S1 to S5) p. 9 Supplementary Figures (S1 to S15) p. 17 2 SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS Western blot, immunoprecipitation, and qRT-PCR Western blot (WB) analysis was performed as previously described (1), using cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-753, RRID:AB_2070433) and tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, T5168, RRID:AB_477579) antibodies. Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed as described before (2), using cyclin D1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-8396, RRID:AB_627344) or control IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2025, RRID:AB_737182) followed by protein G- magnetic beads (Invitrogen) incubation and elution with Glycine 100mM pH=2.5. Co-IP experiments were performed within five weeks after cell thawing. Cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-753), E2F4 (Bethyl, A302-134A, RRID:AB_1720353), FOXM1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-502, RRID:AB_631523), and CBP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7300, RRID:AB_626817) antibodies were used for WB detection. In figure 1A and supplementary figure S2A, the same blot was probed with cyclin D1 and tubulin antibodies by cutting the membrane. In figure 2H, cyclin D1 and CBP blots correspond to the same membrane while E2F4 and FOXM1 blots correspond to an independent membrane. Image acquisition was performed with ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare). Image processing and quantification were performed with Multi Gauge software (Fujifilm). For qRT-PCR analysis, cDNA was generated from 1 µg RNA with qScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Quantabio). qRT–PCR reaction was performed using SYBR green (Roche). -

AURKA, DLGAP5, TPX2, KIF11 and CKAP5: Five Specific Mitosis-Associated Genes Correlate with Poor Prognosis for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY 50: 365-372, 2017 AURKA, DLGAP5, TPX2, KIF11 and CKAP5: Five specific mitosis-associated genes correlate with poor prognosis for non-small cell lung cancer patients MARC A. SCHNEIDER1,8, PETROS CHristopoulos2,8, THOMAS MULEY1,8, ARNE WartH5,8, URSULA KLINGMUELLER6,8,9, MICHAEL THOMAS2,8, FELIX J.F. HertH3,8, HENDRIK DIENEMANN4,8, NIKOLA S. MUELLER7,9, FABIAN THEIS7,9 and MICHAEL MEISTER1,8,9 1Translational Research Unit, 2Department of Thoracic Oncology, 3Department of Pneumology and Critical Care Medicine, and 4Department of Surgery, Thoraxklinik at University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg; 5Institute of Pathology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg; 6Systems Biology of Signal Transduction, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg; 7Cellular Dynamics and Cell Patterning, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried; 8Translational Lung Research Center Heidelberg (TLRC-H), Member of the German Center for Lung Research (DZL) Heidelberg; 9CancerSys network ‘LungSysII’, Heidelberg, Germany Received October 26, 2016; Accepted December 5, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/ijo.2017.3834 Abstract. The growth of a tumor depends to a certain extent genes AURKA, DLGAP5, TPX2, KIF11 and CKAP5 is asso- on an increase in mitotic events. Key steps during mitosis are ciated with the prognosis of NSCLC patients. the regulated assembly of the spindle apparatus and the sepa- ration of the sister chromatids. The microtubule-associated Introduction protein Aurora kinase A phosphorylates DLGAP5 in order to correctly segregate the chromatids. Its activity and recruitment Lung cancer is globally the leading cause of cancer-related to the spindle apparatus is regulated by TPX2. KIF11 and deaths (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts CKAP5 control the correct arrangement of the microtubules for more than 80% of all cases, is divided in adenocarcinoma and prevent their degradation. -

Downloaded the “Top Edge” Version

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/855338; this version posted December 6, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Drosophila models of pathogenic copy-number variant genes show global and 2 non-neuronal defects during development 3 Short title: Non-neuronal defects of fly homologs of CNV genes 4 Tanzeen Yusuff1,4, Matthew Jensen1,4, Sneha Yennawar1,4, Lucilla Pizzo1, Siddharth 5 Karthikeyan1, Dagny J. Gould1, Avik Sarker1, Yurika Matsui1,2, Janani Iyer1, Zhi-Chun Lai1,2, 6 and Santhosh Girirajan1,3* 7 8 1. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Pennsylvania State University, 9 University Park, PA 16802 10 2. Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 11 3. Department of Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 12 4 contributed equally to work 13 14 *Correspondence: 15 Santhosh Girirajan, MBBS, PhD 16 205A Life Sciences Building 17 Pennsylvania State University 18 University Park, PA 16802 19 E-mail: [email protected] 20 Phone: 814-865-0674 21 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/855338; this version posted December 6, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 22 ABSTRACT 23 While rare pathogenic copy-number variants (CNVs) are associated with both neuronal and non- 24 neuronal phenotypes, functional studies evaluating these regions have focused on the molecular 25 basis of neuronal defects. -

An Unconventional Interaction Between Dis1/TOG and Mal3/EB1 in Fission Yeast Promotes the Fidelity of Chromosome Segregation Yuzy Matsuo1,2, Sebastian P

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2016) 129, 4592-4606 doi:10.1242/jcs.197533 RESEARCH ARTICLE An unconventional interaction between Dis1/TOG and Mal3/EB1 in fission yeast promotes the fidelity of chromosome segregation Yuzy Matsuo1,2, Sebastian P. Maurer1,3,4, Masashi Yukawa5, Silva Zakian6, Martin R. Singleton6, Thomas Surrey1,* and Takashi Toda2,5,* ABSTRACT (Mitchison and Kirschner, 1984). Such dynamic properties of Dynamic microtubule plus-ends interact with various intracellular MTs play an essential role in many cellular processes including target regions such as the cell cortex and the kinetochore. Two intracellular transport, cell polarity and cell division (Desai and conserved families of microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins, the Mitchison, 1997). MT dynamics are regulated by a cohort of XMAP215, ch-TOG or CKAP5 family and the end-binding 1 (EB1, evolutionarily conserved MT-associated proteins (MAPs) also known as MAPRE1) family, play pivotal roles in regulating (Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2008). A subclass of MAPs, MT microtubule dynamics. Here, we study the functional interplay plus-end-tracking proteins (+TIPs) have unique properties, as they between fission yeast Dis1, a member of the XMAP215/TOG can specifically interact with the dynamic ends of MTs, thereby family, and Mal3, an EB1 protein. Using an in vitro microscopy playing a decisive role in determining the characteristics of MT assay, we find that purified Dis1 autonomously tracks growing plus-ends in cells (Buey et al., 2012; Duellberg et al., 2013). In microtubule ends and is a bona fide microtubule polymerase. Mal3 particular, end-binding 1 (EB1, also known as MAPRE1) and Xenopus Homo recruits additional Dis1 to microtubule ends, explaining the ch-TOG [known as XMAP215 ( ) and CKAP5 ( sapiens synergistic enhancement of microtubule dynamicity by these ); hereafter denoted TOG] are important +TIPs because they proteins. -

Gadd45a Regulates B-Catenin Distribution and Maintains Cell–Cell Adhesion/ Contact

Oncogene (2007) 26, 6396–6405 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Gadd45a regulates b-catenin distribution and maintains cell–cell adhesion/ contact JJi1, R Liu1, T Tong, Y Song, S Jin, M Wu and Q Zhan State Key Laboratory of Molecular Oncology, Cancer Institute, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, PR China Gadd45a,a growth arrest and DNA-damage gene,plays 1999;Jin et al., 2000;Tong et al., 2005). Gadd45a important roles in the control of cell cycle checkpoints, also plays roles in negative regulation of cell malig- DNA repair and apoptosis. We show here that Gadd45a is nancy. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived involved in the control of cell contact inhibition and cell– from Gadd45a-null mice exhibited genomic instability, cell adhesion. Gadd45a can serve as an adapter to enhance single oncogene-mediated transformation, loss of nor- the interaction between b-catenin and Caveolin-1,and in mal cellular senescence, increased cellular proliferation, turn induces b-catenin translocation to cell membrane for centrosome amplification and reduced DNA repair maintaining cell–cell adhesion/contact inhibition. This is (Hollander et al., 1999;Smith et al., 2000). Gadd45a- coupled with reduction of b-catenin in cytoplasm and null mice have an increased frequency of tumorigenesis nucleus following Gadd45a induction,which is reflected by by ionizing radiation (IR), ultraviolet radiation (UVR) the downregulation of cyclin D1,one of the b-catenin and dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA), although these targeted genes. Additionally,Gadd45a facilitates ultra- mice do not develop spontaneous tumors (Hollander violet radiation-induced degradation of cytoplasmic and et al., 1999, 2001;Hildesheim et al., 2002). -

DNA Excision Repair Proteins and Gadd45 As Molecular Players for Active DNA Demethylation

Cell Cycle ISSN: 1538-4101 (Print) 1551-4005 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/kccy20 DNA excision repair proteins and Gadd45 as molecular players for active DNA demethylation Dengke K. Ma, Junjie U. Guo, Guo-li Ming & Hongjun Song To cite this article: Dengke K. Ma, Junjie U. Guo, Guo-li Ming & Hongjun Song (2009) DNA excision repair proteins and Gadd45 as molecular players for active DNA demethylation, Cell Cycle, 8:10, 1526-1531, DOI: 10.4161/cc.8.10.8500 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.8.10.8500 Published online: 15 May 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 135 View related articles Citing articles: 92 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=kccy20 Download by: [University of Pennsylvania] Date: 27 April 2017, At: 12:48 [Cell Cycle 8:10, 1526-1531; 15 May 2009]; ©2009 Landes Bioscience Perspective DNA excision repair proteins and Gadd45 as molecular players for active DNA demethylation Dengke K. Ma,1,2,* Junjie U. Guo,1,3 Guo-li Ming1-3 and Hongjun Song1-3 1Institute for Cell Engineering; 2Department of Neurology; and 3The Solomon Snyder Department of Neuroscience; Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Baltimore, MD USA Abbreviations: DNMT, DNA methyltransferases; PGCs, primordial germ cells; MBD, methyl-CpG binding protein; NER, nucleotide excision repair; BER, base excision repair; AP, apurinic/apyrimidinic; SAM, S-adenosyl methionine Key words: DNA demethylation, Gadd45, Gadd45a, Gadd45b, Gadd45g, 5-methylcytosine, deaminase, glycosylase, base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair DNA cytosine methylation represents an intrinsic modifica- silencing of gene activity or parasitic genetic elements (Fig. -

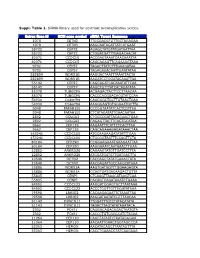

Suppl. Table 1

Suppl. Table 1. SiRNA library used for centriole overduplication screen. Entrez Gene Id NCBI gene symbol siRNA Target Sequence 1070 CETN3 TTGCGACGTGTTGCTAGAGAA 1070 CETN3 AAGCAATAGATTATCATGAAT 55722 CEP72 AGAGCTATGTATGATAATTAA 55722 CEP72 CTGGATGATTTGAGACAACAT 80071 CCDC15 ACCGAGTAAATCAACAAATTA 80071 CCDC15 CAGCAGAGTTCAGAAAGTAAA 9702 CEP57 TAGACTTATCTTTGAAGATAA 9702 CEP57 TAGAGAAACAATTGAATATAA 282809 WDR51B AAGGACTAATTTAAATTACTA 282809 WDR51B AAGATCCTGGATACAAATTAA 55142 CEP27 CAGCAGATCACAAATATTCAA 55142 CEP27 AAGCTGTTTATCACAGATATA 85378 TUBGCP6 ACGAGACTACTTCCTTAACAA 85378 TUBGCP6 CACCCACGGACACGTATCCAA 54930 C14orf94 CAGCGGCTGCTTGTAACTGAA 54930 C14orf94 AAGGGAGTGTGGAAATGCTTA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CCCGGTAATATCACTCGTTAA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CTCATAGATATTGAACAATAA 2802 GOLGA3 CTGGCCGATTACAGAACTGAA 2802 GOLGA3 CAGAGTTACTTCAGTGCATAA 9662 CEP135 AAGAATTTCATTCTCACTTAA 9662 CEP135 CAGCAGAAAGAGATAAACTAA 153241 CCDC100 ATGCAAGAAGATATATTTGAA 153241 CCDC100 CTGCGGTAATTTCCAGTTCTA 80184 CEP290 CCGGAAGAAATGAAGAATTAA 80184 CEP290 AAGGAAATCAATAAACTTGAA 22852 ANKRD26 CAGAAGTATGTTGATCCTTTA 22852 ANKRD26 ATGGATGATGTTGATGACTTA 10540 DCTN2 CACCAGCTATATGAAACTATA 10540 DCTN2 AACGAGATTGCCAAGCATAAA 25886 WDR51A AAGTGATGGTTTGGAAGAGTA 25886 WDR51A CCAGTGATGACAAGACTGTTA 55835 CENPJ CTCAAGTTAAACATAAGTCAA 55835 CENPJ CACAGTCAGATAAATCTGAAA 84902 CCDC123 AAGGATGGAGTGCTTAATAAA 84902 CCDC123 ACCCTGGTTGTTGGATATAAA 79598 LRRIQ2 CACAAGAGAATTCTAAATTAA 79598 LRRIQ2 AAGGATAATATCGTTTAACAA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TTGGATTTGTCTATACATATA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TAGACTTAGTATATAAATACA 2302 FOXJ1 CAGGACAGACAGACTAATGTA