Mrs E Smith V Govia Thameslink Railway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Review Report

Item Scrutiny Panel 10 16 March 2018 Report of Assistant Director of Policy and Author Jonathan Baker Corporate 282207 Title Bus Review Wards Not applicable affected 1. Executive Summary 1.1 The Scrutiny Panel at its meeting in September 2017 agreed to review the bus services operating in Colchester. As part of this review the Panel have invited bus companies, Essex County Council and a Community Transport provider to this meeting as part of an information gathering session. 1.2 The review will follow the objectives as agreed at the September meeting. These are included below - To understand the strategic role and benefits of bus operation and how it can best serve the community. To investigate and scrutinise what bus companies are doing to; . Improve the punctuality of services . Increase bus usage . Reduce emissions . Make buses more accessible . Communicate with passengers when services are cancelled or altered. To improve the dialogue between bus companies that operate in the Borough and Colchester Borough Council, Councillors and Residents. 1.3 This meeting has been arranged following the postponement, due to severe weather, of the original bus review date in February. 1.4 Following on from the review, the Panel may wish to schedule a further discussion at an upcoming meeting to decide the next steps of the review. 2. Action Required 2.1 To undertake an information gathering session, in line with the bus review objectives prior to deciding on the next steps. 3. Reason for Scrutiny 3.1 The Panel received a request from a member of the Panel to review bus services in Colchester. -

Focused on Partnership About Us

Go East Anglia Sustainability Report 2016 Focused on partnership About us Go East Anglia encompasses Anglianbus, Chambers, Hedingham and Konectbus. Some 8 million passenger journeys are made each year on its services and over 370 people are employed. The forming of the branding name Go East Anglia was designed in 2015 to bring together the separate business in terms of identifying opportunities to work collectively across the geography and introduce the idea of sharing best practice with being part of a wider group. Our network covers Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex providing essential links to local towns and hospitals and places of education. Places served include Norwich, Great Yarmouth, Lowestoft, Bury St Edmunds, Sudbury, Braintree, Colchester and Clacton. Where we operate Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex. Norwich Swaffham Great Yarmouth Lowestoft Bury St Edmunds Sudbury Colchester Braintree Clacton-on-Sea We’re part of The Group In this report 2 Managing Director’s message 6 Society 4 Our approach 8 Customers 5 Our stakeholders 10 Our people 12 Finance Highlights – Launch of new Norwich Park & Ride network 9% 8,018,153 increase in passengers passenger journeys – Norwich Park & Ride m-ticket app journeys goes live – Buses with USB charging points enter service – Introduction of 5S in the workplace – Shortlisted for UKBA National Bus 89% 46% average customer increase in buses Driver of the Year satisfaction score fitted with CCTV Website: Twitter: Facebook: www.anglianbus.co.uk anglianbus anglianbus www.chambersbus.co.uk chambersbus chambersbus -

Go East Anglia

Go East Anglia - Chambers, Hedingham, Konect Bus (PF0002189) Konect Bus Limited 5-7 John Goshawk Road, Rashes Green Industrial Estate, Dereham, Norfolk, NR19 1SY Part of the Go-Ahead Group PLC. Depots: Clacton-on-Sea Stephenson Road, Gorse Lane Industrial Estate, Clacton-on-Sea, Essex, CO15 4XA Colchester Wethersfield Road, Sible Hedingham, Halstead, Colchester, Essex, CO9 3LB Dereham 7 John Goshawk Road, Rashes Green Industrial Estate, Dereham, Norfolk, NR19 1SY Sudbury Windham Road, Meekings Road, Chilton Industrial Estate, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 6XE Outstations: Brunel Road 14 Brunel Road, Gorse Lane Industrial Estate, Clacton-on-Sea, Essex, CO15 4LU Kelvedon 215-217 High Street, Kelvedon, Colchester, Essex, CO5 9JT Rackheath 36R Ramirez Road, Rackheath Industrial Estate, Norwich, Norfolk, NR13 6LR Chassis Type: Mercedes-Benz 1836RL Body Type: Mercedes-Benz Touro Fleet No: Reg No: Layout: Year: Depot: Livery: Notes: 1 BX55FYH C49FT 2006 Colchester Chambers 2 BX55FYJ C49FT 2006 Colchester Chambers Chassis Type: Alexander-Dennis Enviro 200MMC Body Type: Alexander-Dennis Enviro 200MMC Fleet No: Reg No: Layout: Year: Depot: Livery: Notes: 200 YX69NPE B42F 2019 Dereham park & ride Norwich 201 YX69NPF B42F 2019 Dereham park & ride Norwich 202 YX69NPG B42F 2019 Dereham park & ride Norwich Chassis Type: Dennis Dart SLF Body Type: Plaxton Pointer 2 Fleet No: Reg No: Layout: Year: Depot: Livery: Notes: 253 EU04BVF B37F 2004 Clacton-on-Sea Hedingham BLT, 2012 Previous Owners: BLT, 2012: Blue Triangle, 2012 254 - 260 Chassis Type: Alexander-Dennis Dart SLF Body Type: Plaxton Pointer 2 Fleet No: Reg No: Layout: Year: Depot: Livery: Notes: 254 EU05AUR B37F 2005 Clacton-on-Sea Hedingham 255 EU05AUT B37F 2005 Clacton-on-Sea Hedingham 256 EU55BWC B37F 2005 Clacton-on-Sea Hedingham 257 EU56FLM B37F 2006 Clacton-on-Sea Hedingham 258 EU56FLN B37F 2006 Clacton-on-Sea Hedingham 259 EU56FLP B37F 2006 Colchester Hedingham 260 EU56FLR B37F 2006 Clacton-on-Sea Hedingham Unofficial fleet list compiled by www.ukbuses.co.uk - last updated Friday, 20 August 2021. -

NOTICES and PROCEEDINGS 18 March 2015

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2201 PUBLICATION DATE: 18 March 2015 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 08 April 2015 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 01/04/2015 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e -mail. To use this service please send an e- mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage -commercial -vehicle -operator -licence -online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. -

“Outstanding, Confident, Direct and Eminently Approachable” “Very Impressive She Really Grasps the Complexities in a Case

Katherine Apps Year called 2006 [email protected] “Outstanding, confident, direct and eminently approachable” Legal 500 “Very impressive she really grasps the complexities in a case” Chambers and Partners “Extremely clever and the right person to go to with a difficult and novel point of law” Legal 500 “Simply brilliant; one of the best juniors around” Legal 500 “She can think through cutting-edge issues of law in an impressive way” Legal 500 Katherine’s practice spans public and human rights law, disciplinary/ regulatory, EU, employment and commercial law. She has particular expertise in appellate advocacy and in domestic and international equality law. Described as “incredibly bright,” “very good with clients” and a “pleasure to deal with” who “gives solid advice,” Katherine has been appointed to the Attorney General’s A Panel of Counsel and the EHRC B Panel of Counsel. She BARRISTERS • ARBITRATORS • MEDIATORS [email protected] • DX: 298 London/Chancery Lane • 39essex.com is an arbitrator for Sports Resolutions panels on Commercial Disputes, Integrity and Discipline, Discrimination and the National Safeguarding Panel. Katherine works for a wide range of clients: from Government Departments, HMRC and local authorities to Trade Unions; individuals to multinational companies and Receivers. She is a graduate of Harvard Law School’s LL.M programme and former stagiere at the Court of Justice of the European Union. Her key cases include R(Coll) v Ministry of Justice on single sex provision of services, Govia Thameslink Railway and ASLEF, on EU law and strike action (the Southern Trains Dispute) and W v M, withholding and withdrawing treatment from a person in the minimally conscious state. -

Notices and Proceedings 23 July 2014

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2184 PUBLICATION DATE: 23 July 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 13 August 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 06/08/2014 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. -

NOTICES and PROCEEDINGS 11 November 2015

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2218 PUBLICATION DATE: 11 November 2015 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 02 December 2015 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic -commis sioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 25 th November 2015 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e -mail. To use this service please send an e- mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage -commercial -vehicle -operator -licence -online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. -

Hedingham/Chambers

15-Aug-16 99 Fleet No. Depot Reg No. Model Seating First reg. Acquired from/date Low floor? Livery 1 L440 SY BX55 FYH Mercedes Benz Touro 49 2006 New 2006 No (Coach) CHAMBERS 2 L441 SY BX55 FYJ Mercedes Benz Touro 49 2006 New 2006 No (Coach) CHAMBERS 3 L439 SY M655 KVU Volvo B10M Van Hool Alizée T8 49 1995 Shearings 2003 No (Coach) CHAMBERS 5 L295 SY N664 THO Volvo B10M Plaxton Premiere 320 53 1995 Excelsior 1998 No (Coach) Hedingham 6 L298 CN N667 THO Volvo B10M Plaxton Premiere 320 53 1996 Excelsior 1999 No (Coach) Hedingham 8 L309 CN R453 FWT Volvo B10M Plaxton Premiere 320 53 1997 Wallace Arnold 2000 No (Coach) Hedingham 9 L290 SY S290 TVW Volvo B10M Plaxton Premiere 320 53 1998 New 1998 No (Coach) Hedingham 10 L291 SY S291 TVW Volvo B10M Plaxton Premiere 320 53 1998 New 1998 No (Coach) Hedingham 11 L347 CN W649 FUM Volvo B10M Plaxton Premiere 350 53 2000 Wallace Arnold 2006 No (Coach) Hedingham 67 L375 KN P605 CAY Volvo Olympian Northern Counties Palatine 47/29 1996 Arriva 2009 No Hedingham 70 L379 KN P612 CAY Volvo Olympian Northern Counties Palatine 47/29 1996 Arriva 2009 No Hedingham 71 L372 KN R626 MNU Volvo Olympian Northern Counties Palatine 47/29 1998 Arriva 2009 No Hedingham 72 L373 KN R629 MNU Volvo Olympian Northern Counties Palatine 47/29 1998 Arriva 2009 No Hedingham 73 L374 KN R643 MNU Volvo Olympian Northern Counties Palatine 47/29 1998 Arriva 2009 No Hedingham 74 L384 KN R702 DNH Volvo Olympian Alexander RL 51/36 1997 Stagecoach 2010 No Hedingham 75 L300 KN S300 XHK Volvo Olympian Alexander RL 51/36 1999 New 1999 No -

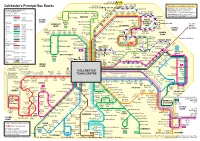

Colchester's Principal Bus Routes

Colchester P&R P&R Junction 28 off A12 New Easter New Link Weston Homes Link Road Park Road East Bus tickets covering Colchester Inner Zone Colchester’s Principal Bus Routes Community Stadium AXIAL WAY Cuckoo Point Day Rover (multi-operator First and Arriva) Monday to Saturday day time routes Borough Card weekly to annual tickets with up to hourly frequency P&R The Crescent Nat Water Maximus Julian Matchett (mult-operator - First, Arriva and Hedinghams) Bus number Route Approximate frequency Blackbrook Road Boxted Road Mile End pm Tower Drive Avenue Drive Office Village West 2 Defoe Single operator weekly to annual tickets Arriva/Network Colchester 11 (First and Arriva) MILE END Crescent am Business Single operator family tickets 1 12 mins Coach Keelers Way Centre 2 20 mins OUTER Road NORTH 8 10 mins/10-20 mins Mill P&R Severalls Lane Crown Gate ZONE Dog and Pheasant only Bedford Road COLCHESTER First Essex Malvern Road VIA URBIS ROMANAE Brinkley am BUSINESS peak hours only 103, 104 to HORKESLEY Mile End Church MILL 61 15 mins Way Lane pm Ardleigh, 62 62A 15 mins HEATH ROAD HIGHWOODS PARK 2 Tall Trees Kingswood Road Cattle Manningtree 64 64A 10 mins Warwick Market OUTER and Harwich 65 15 mins/10-15 mins 754 to School Armoury Bakers Golf Bailey Oaks Place General Hospital Highclere 65 ZONE 66 66A 15 mins Bures and Top Notch 8 11 Sudbury Lane Road Lane Club Close Road Derwent 67 67A 67D 20 mins Wedgewood Health Club INNER Primary Care Centre Road ZONE 70 20 mins BERGHOLTBRAISWICK/ ROADDrive 71 30 mins ROAD END MILE Highwoods Turner Rise 74 76 60 mins Tufnell Way Spindle Wood Baronia Approach Welshwood Park Road 75 30 mins Lexden Road/ Highwoods Hall Road Tesco 2 Croft PARSONS HEATH 103 104 30 mins Albany Road Post Office 2 65 Arden Close 66 Bruff Close 65 Pinecroft Hedingham Omnibus Bricklayers Arms 2 8 61 65 Gardens St. -

NEWS ACROSS the GROUP November 2019 Fire up the Engines! Go-Ahead London’S Transition to Electric Set the World on Fire

Take a look... November 2019 3 1,000 apprentices NEWS ACROSS and growing 7 O-Bee-Cee makes honey 8 Mental health THE GROUP matters A message from David Brown Hello everyone, Another good news story is that we’ve This unfortunately resulted in the death passed our target to bring in 1,000 of one of our drivers, Kenneth Matcham. This month I was especially proud that apprentices with plenty of time to spare Kenneth was 60 years old and had Go-Ahead London received the “Nobel (page 3). That means we’ve doubled the worked at Go-Ahead London for 12 years. Prize for Nature” in Helsinki (page 2) number of apprentices across our rail I have never known of a road accident for its electric bus garage in Waterloo. and bus businesses, which is a landmark resulting in the death of a bus driver and This recognition means we’ve been step in making sure we are as diverse was shocked and saddened by the news. acknowledged on a global scale for as possible. Apprenticeships, along My thoughts are with his family, friends our efforts in promoting sustainable with graduate schemes and colleague and colleagues, and I am immensely transport, and highlighting its role in networks are all activities we use to proud of the way the bus community tackling poor air quality and congestion. develop colleagues and champion came together for a minute’s silence in We continue to develop for the future of diversity. This month’s back cover his memory. interview features two graduates from transport. -

Building a Firm Base for All

Building a firm base for all Go East Anglia Sustainability Report 2019 Sustainability Report 2019 Go East Anglia C Go East Anglia operates bus services across Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex under the Chambers, Hedingham, Konectbus and Norwich Park & Ride brands. We provide a bus network of routes across towns and villages throughout East Anglia with larger hubs in East Dereham, Norwich, Clacton-on-Sea and Colchester. We carry seven million passengers per year on 159 local bus routes, which includes bespoke school contract operations. We currently employ more than 350 people and continue to attract applicants from the local community with our range of employment and training opportunities. In this report Our reporting structure 02 Managing Director’s message We are committed to operating our 04 Finance buses in a way which helps to put our 05 Stronger communities services at the heart of the communities they serve. 07 Happier customers 08 Better teams This report is split into six sections: 10 Cleaner environment 11 Smarter technology Finance 12 Key data To work together with local authorities to provide efficient and effective solutions. Read more on page 4 Stronger communities To support colleagues with fundraising events that support the local community. Find out more... Read more on page 5 Twitter: Happier customers @konectbus To gain more happy customers and @nparkandride reward colleagues when they receive @hedinghambuses positive feedback. @chambersbus Read more on page 7 Website: konectbus.co.uk Better teams norwichparkandride.co.uk To perform all job roles and tasks chambersbus.co.uk competently to allow further growth. hedingham.co.uk Read more on page 8 Cleaner environment To improve air quality and encourage fuel efficiency at all locations across the business. -

Moving with Our People

Moving with our people... Corporate Responsibility Report 2011 Our award winning local bus companies serve the coastal resorts, cities, national park and beautiful countryside of central southern England. We’re a part of the Group Contents About Go South Coast 1 Safety 4 Message from the Managing Director 2 Environment 5 Passengers 6 Employees 7 Community 8 Data table 9 Go South Coast Corporate Responsibility Report 2011 ABOUT GO SOUTH CoasT Go South Coast is the regional organisation that runs the iconic Wilts & Dorset, Southern Vectis and Bluestar buses. We are also the biggest coach operator in the region and run Unilink and University services in Southampton and Bournemouth. 2011 HIGHLIGHTS • Awarded £9m contract to provide comprehensive transport services for Dorset County Council • Secured prestigious student transport network contract for Alton College, extending our operating area east • Rolled out ITSO compliant technology across Go South Coast • Signed a unique partnership with the Isle of Wight Council to deliver an integrated contract for public and school transport, including responsibility for transport of Special Education Needs students WHERE WE OPERATE We operate over 800 buses and coaches across the counties of Dorset, Hampshire, Wiltshire and the Isle of Wight and within the cities of Bournemouth, Southampton and Salisbury. www.gosouthcoast.co.uk www.gosouthcoast.co.uk 1 OUR BRANDS 2 Go South Coast Corporate Responsibility Report 2011 MESSAGE FROM ALEX CARTER, MANAGING DIRECTOR Our responsibilities within Welcome to Go South Coast’s Corporate Responsibility report the communities we for the year 2010/11. operate are fundamental Across central Southern England we operate a diverse range of bus, coach and support businesses, each of them closely aligned to the principles behind with local markets and customer needs.