Community Inventory Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection: DEITRICK, IHLLIAN HENLEY Papers Wake County, Raleigh [1858-185~)

p,C 1487.1-.31 Collection: DEITRICK, IHLLIAN HENLEY Papers Wake County, Raleigh [1858-185~). 1931-1974 Physieal Deseription: 13 linear feet plus 1 reel microfilm: correspondence, photographs, colored slides, magazines, architectural plans, account ledgers business records, personal financial records, etc. Acquisition: ca. 1,659 items donated by William H. Deitrick, 1900 McDonald Lane, Raleigh, July, 1971, with addition of two photocopied letters, 1858 an . 1859 in August 1971. Mr. Deitrick died July 14, 1974, and additional papers were willed to f NC Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. In November, 1974, and July, 1975, these papers were given to the State Archives. In this acquisit are five boxes (P.C. 1487.19-.23) of business correspondence generated durin Mr. Deitrick's association with John A. Park, Jr., an intermediary for busin mergers and sales; these five boxes are RESTRICTED until five years after Mr. Park's death. Description: William Henley Deitrick (1895-1974), son of Toakalito Townes and William Henry Deitrick, born Danville, Virginia; graduate, Wake Forest College, 1916; high school principal (Georgia), 1916-1917; 2nd Lt., U.S. Army, 1917-1919; building contractor, 1919-1922; married Elizabeth Hunter of Raleigh, 1920; student, Columbia University, .1922-1924; practicing architect 19.26-1959; consulting architect, 1959+. Architect, Wake Forest College, 1931-1951; other projects: Western N. C. Sanatorium, N. C. State University (student union), Meredith College (auditorium), Elon College (dormitories and dining hall), Campbell College (dormitory), Shaw University (gymnasium, dormitory, classrooms), St. l1ary's Jr. College (music building), U.N.C. Greensboro.(alumnae house), U.N.C. Chapel Hill (married student nousing), Dorton Arena, Carolina Country Club (Raleigh), Ne,.•s & Observer building,. -

Mordecai Zachary House

NPS Fonn 10-000 OMS No. 1024-{) (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This fom\ Is (Of use in nominating or requesting determinations for indMdual properties and districts, See instructions in How to CompUHe the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by maridng Y in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented. enter ~N/A~ (0( ~not appUcable.~ For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on cootinuation sheets (NPS Form 10-9OOa). Use a typewriter, word processor, 0( computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Mordecai Zachary House other names/site number "Zjj!ac~hliau.O':t.:-:.JT""owlb.15ea.rtLHlliI.O!,"!s"'e'-___________________________ 2. Location street & number West side of NC 107 0.2 miles south of SR 1107 not for publication N/A city or town "C"'as.. hllie"'rs"'- __________________________________ vicinitY0 state North Carolina code NC county "'Ja"'c"'k"SOIlJDlL. ______ code 099 zip code "'28'-'7.... t.1..7 ____ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic PreseNation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ~ nomination 0 request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards fO( registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professKmal requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Venues and Highlights

VENUES AND HIGHLIGHTS 1 EDENTON STREET 8 FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH - Memorial Hall INTERSECTION OF FAYETTEVILLE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH BeBop Blues & All That Jazz | 7:00PM - 11:00PM & DAVIE ST. Triangle Youth Jazz Ensemble | 7:00PM, 9:00PM 2 3 4 Bradley Burgess, Organist | 7:00, 9:00PM Early Countdown & Fireworks with: 1 Sponsored by: Captive Aire Steve Anderson Jazz Quartet | 8:00PM Media Sponsor: Triangle Tribune Open Community Jam | 10:00PM Barefoot Movement | 6:00-7:00PM Sponsored by: First Citizens Bank 5 Early Countdown | 7:00PM NORTH CAROLINA MUSEUM OF Media Sponsor: 72.9 The Voice 6 2 NATURAL SCIENCES Fireworks | 7:00PM Children’s Celebration | 2:00-6:00PM 9 MORGAN ST. - GOLD LEAF SLEIGH RIDES Gold Leaf Sleigh Rides | 8:00 -11:00PM Celebrate New Year’s Eve with activities including henna, Boom Unit Brass Band | 7:30-8:30PM Sponsored by: Capital Associates resolution frames, stained glass art, celebration bells, a Media Sponsor: Spectacular Magazine Caleb Johnson 7 toddler play area, and more. Media Sponsor: GoRaleigh - City of Raleigh Transit & The Ramblin’ Saints | 9:00-10:00PM 10 TRANSPORTATION / HIGHWAY BUILDING 10 Illiterate Light | 10:30PM-12:00AM BICENTENNIAL PLAZA Comedy Worx Improv | 7:30, 8:45, 10:15PM 3 Sponsored by: Capital Investment Companies 9 Children’s Celebration | 2:00-6:00PM Media Sponsor: City Insight Countdown to Midnight | 12:00AM Celebrate New Year’s Eve with interactive activities 11 including the First Night Resolution Oak, a New Year’s Fireworks at Midnight | 12:00AM FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH WILMINGTON ST. 8 castle construction project, a Midnight Mural, and more. -

Bring Your Family Back to Cary. We're in the Middle of It All!

Bring Your Family Back To Cary. Shaw Uni- versity North Carolina State University North Carolina Museum of Art Umstead State Park North Carolina Museum of History Artspace PNC Arena The Time Warner Cable Music Pavilion The North Carolina Mu- seum of Natural History Marbles Kids Museum J.C. Raulston Arbore- tum Raleigh Little Theatre Fred G. Bond Metro Park Hemlock Bluffs Nature Preserve Wynton’s World Cooking School USA Baseball Na- tional Training Center The North Carolina Symphony Raleigh Durham International Airport Bond Park North Carolina State Fairgrounds James B. Hunt Jr. Horse Complex Pullen Park Red Hat Amphitheatre Norwell Park Lake Crabtree County Park Cary Downtown Theatre Cary Arts Center Page-Walker Arts & History Center Duke University The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill We’re in the middle of it all! Book your 2018 or 2019 family reunion with us at an incredible rate! Receive 10% off your catered lunch or dinner of 50 guests or more. Enjoy a complimen- tary upgrade to one of our Hospitality suites or a Corner suite, depending on availability. *All discounts are pretax and pre-service charge, subject to availability. Offer is subject to change and valid for family reunions in the year 2018 or 2019. Family reunions require a non-refundable deposit at the time of signature which is applied to the master bill. Contract must be signed within three weeks of receipt to take full advantage of offer. Embassy Suites Raleigh-Durham/Research Triangle | 201 Harrison Oaks Blvd, Cary, NC 27153 2018 www.raleighdurham.embassysuites.com | 919.677.1840 . -

Rev. Debnam Speaker for Oak City Church Program Rev

CLIPPING SERVice 1115 HILLSBORO RALEIGH, NC 27603 ~ TEL (919) 833-2079 CAROLINIAN RAlElGti, N.~ OCT 22 92 () ttl Rev. Debnam Speaker For Oak City Church Program Rev. Leotha Debnam, pastor of . '!'upper Memorial Baptist Church, will be the featured spader at the 11 a.m. homecoming/church anni versary service at Oak City Bap tist Church, 608 Method Road, Sunday. Dr. Debnam is a native of Raleigh and a product of the Raleigh public school system. Dr. Debnam attended St. Augustine's College and upon his discharge from the Army, he completed his studies at N.C. A8tT State Univer sity. He completed studies at American University, Washington, D.C.; Shaw University School of Religion and Duke Divinity .Sch ool. Dr. Debnam is a well-known educator and minister who has served on many boards and com REV. LEOTHA DEBNAM missions in Raleigh and is cur rently a member of the Board of nity Day Care Center. Management of the Estey Han The public is invited to attend . Fou~d a~;c.n and Tuttle C('!!lmu- this service. CUPPING SERVICE 1115 HIllSBORO RALEIGH. NC 27603 ?" TEL . (919)833.2079 CAROLINIAN RALEIGH, N. C. DEC-20-R4 APPRECIATION ADDHESS- TIle Hlv. LIIIIII Dlbnlm, plltor of Tupper Mlmorlal ~IP"lt Church, was Ihe keynote lpelklr at thl Chartel T. Mlrwood PIli 157 apprtCII"ln .",1It IIIId IICInlly. Till Allltlfca. LI.lln IIIId III flrll aChl..I"";I. ..lnII IIInqull In reclnl years 10· honor Ileal selected wlr "lIranl. During hlalpleCh, Rev. DlbaIaa tiId.aI 1111 "cal li the mIIIIItry" during ilia .ar nrvlcl. -

Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston the Story of How One of the Oldest American Cities Became the Epicenter of Concrete Modernist Architecture

Media Contact: Dan Scheffey Ellen Rubin [email protected] [email protected] (212) 979-0058 (212) 909-2625 HEROIC: CONCRETE ARCHITECTURE AND THE NEW BOSTON THE STORY OF HOW ONE OF THE OLDEST AMERICAN CITIES BECAME THE EPICENTER OF CONCRETE MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE As a worldwide phenomenon, concrete modernism represents one of the major architectural movements of the postwar years, but in Boston it was more transformative across civic, cultural, and academic projects than in any other major city in the United States. Concrete provided an important set of architectural opportunities and challenges for the design community, which fully explored the material’s structural and sculptural qualities. From 1960 to 1976, concrete was used by some of the world's most influential architects in the transformation of Boston including Marcel Breuer, Eduardo Catalano, Henry N. Cobb, Araldo Cossutta, Kallmann and McKinnell, Le Corbusier, I. M. Pei, Paul Rudolph, Josep Lluís Sert, and The Architects Collaborative—creating a vision for the city’s widespread revitalization under the banner of the “New Boston.” Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston presents the historical context and new critical profiles of the buildings that defined Boston during this remarkable period, showing the city as a laboratory for refined experiments in concrete and new strategies in urban planning. Heroic further adds to our understanding of the movement’s broader implications through essays by noted historians and interviews with several key practitioners of HEROIC: Concrete Architecture the time: Peter Chermayeff, Henry N. Cobb, Araldo Cossutta, Michael and the New Boston McKinnell, Tician Papachristou, Tad Stahl, and Mary Otis Stevens. -

Bus Review Report

Item Scrutiny Panel 10 16 March 2018 Report of Assistant Director of Policy and Author Jonathan Baker Corporate 282207 Title Bus Review Wards Not applicable affected 1. Executive Summary 1.1 The Scrutiny Panel at its meeting in September 2017 agreed to review the bus services operating in Colchester. As part of this review the Panel have invited bus companies, Essex County Council and a Community Transport provider to this meeting as part of an information gathering session. 1.2 The review will follow the objectives as agreed at the September meeting. These are included below - To understand the strategic role and benefits of bus operation and how it can best serve the community. To investigate and scrutinise what bus companies are doing to; . Improve the punctuality of services . Increase bus usage . Reduce emissions . Make buses more accessible . Communicate with passengers when services are cancelled or altered. To improve the dialogue between bus companies that operate in the Borough and Colchester Borough Council, Councillors and Residents. 1.3 This meeting has been arranged following the postponement, due to severe weather, of the original bus review date in February. 1.4 Following on from the review, the Panel may wish to schedule a further discussion at an upcoming meeting to decide the next steps of the review. 2. Action Required 2.1 To undertake an information gathering session, in line with the bus review objectives prior to deciding on the next steps. 3. Reason for Scrutiny 3.1 The Panel received a request from a member of the Panel to review bus services in Colchester. -

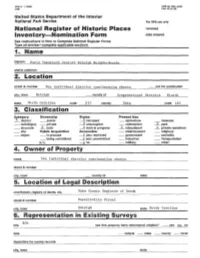

National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form 1

NPS FG--' 10·900 OMS No. 1024-0018 (:>82> EXP·10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS u.e only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See Instructions In How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Early -r«entieth Century Raleigh Neighborhoods andlor common 2. Location street & number See individual district continuation sheets _ not for publication city, town Raleigh _ vicinitY of Congressional District Fourth state North Carolina code 037 county Hake code 183 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use ~dlstrlct _public ----.K occupied _ agriculture _museum _ bulldlng(s) _private J unoccupied _ commercial X park _ structure -'L both ----X work In progress l educational l private residence _site Public Acquisition Accessible _ entertainment _ religious _object _In process ----X yes: restricted _ government _ scientific _ being considered --X yes: unrestricted _ Industrial _ transportation N/A -*no _ military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name See individual dis trict continuation sheets street & number city, town _ vicinitY of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Hake County Register of Deeds street & number Fayetteville Street city, town Raleigh state North Carolina 6. Representation in Existing Surveys NIA title has this property been determined eligible? _ yes XX-- no date _ federal __ state _ county _ local depository for survey records city, town state ·- 7. Description Condition Check one Check one ---K excellent -_ deteriorated ~ unaltered ~ original site --X good __ ruins -.L altered __ moved date _____________ --X fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Description: Between 1906 and 1910 three suburban neighborhoods -- Glenwood, Boylan Heights and Cameron Park -- were platted on the northwest, west and southwest sides of the City of Raleigh (see map). -

A Walking Tour of City Cemetery

Tradition has it that Wm Henry Haywood, Jr., (1801- way was established. Finished in January 1833 it was Geddy Hill (1806-1877) was a prominent Raleigh physi 1846), is buried near his sons, Duncan Cameron and Wm. considered the first attempt at a railroad in N' C The cian and a founder of the Medical Society of North Caro Henry, both killed in the Civil War; but his tombstone railroad was constructed to haul stone from' a local Una. is gone. Haywood was a U. S. Senator. He declined ap quarry to build the present Capitol. Passenger cars were pointment by President Van Buren as Charge d'Affairs placed upon it for the enjoyment of local citizens. 33. Jacob Marling (d. 1833). Artist. Marling painted to Belgium. Tracks ran from the east portico of the Capitol portraits in water color and oils of numerous members to the roek quarry in the eastern portion of the city Mrs. of the General Assembly and other well-known personages 18. Josiah Ogden Watson (1774-1852). Landowner. Polk was principal stockholder and the investment re Known for his landscape paintings, Marling's oil-on-canvas Watson was active in Raleigh civic life, donating money portedly paid over a 300 per cent return. painting of the first N. C. State House hangs in the for the Christ Church tower. His home, "Sharon," belong N. C. Museum of History. ed at one time to Governor Jonathan Worth A WALKING 34. Peace Plot. The stone wall around this plot was 19. Romulus Mitchell Saunders (1791-1867). Lawyer designed with a unique drainage system which prevents and statesman. -

Doing Business Search - People

Doing Business Search - People MOCS PEOPLE ID ORGANIZATION NAME 50136 CASTLE SOFTWARE INC 158890 J2 147-07 94TH AVENUE LI LLC 160281 SDF67 SPRINGFIELD BLVD OWNER LLC 129906 E-J ELECTRIC INSTALLATION CO. 63414 NEOPOST USA INC 56283 MAKE THE ROAD NEW YORK 53828 BOSTON TRUST & INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT COMPANY 89181 FALCON BUILDER INC 105272 STERLING INFOSYSTEMS INC 107736 SIEGEL & STOCKMAN 160919 UTECH PRODUCTS INC 49631 LIRO GIS INC. 12881 THE GORDIAN GROUP INC. 64818 ZUCKER'S GIFTS INC 52185 JAMAICA CENTER FOR ARTS & LEARNING INC 146694 GOOD SHEPHERD SERVICES 156009 ATOMS INC. 116226 THE MENTAL HEALTH ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK CITY INC. 150172 SOSA USA LLC Page 1 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People PERSON FIRST NAME PERSON MIDDLE NAME SCOTT FRANK C NATALIE DEBORAH L LUCIA B MEHMET ANDREW PHILIPPE J JAMES J MICHAEL HARRY H MARVIN CATHY HUIYING RACHEL SIDRA SUSAN UZI B Page 2 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People PERSON LAST NAME PERSON_NAME_SUFFIX FISCHER PRG NATIONAL URBAN FUNDS LLC SULLIVAN DEBT FUND HLDINGS LLC LAMBRAIA ADAIR AXT SANTINI PALAOGLU REIBEN DALLACORTE COSTANZO BAILEY MELLON STERNBERG HUNG KITAY QASIM SHANKLIN SCHEFFER Page 3 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People RELATIONSHIP TYPE CODE MCT EWN EWN MCT MCT CFO OWN CFO CFO CEO MCT MCT MCT CEO CEO MCT COO COO CEO Page 4 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People DOING BUSINESS START DATE 09/21/0016 11/20/0019 01/14/0020 03/10/0016 08/08/0008 04/03/0021 11/19/0008 06/02/0014 09/02/0016 03/03/0013 04/03/0021 06/02/0018 08/02/0008 12/05/0008 04/14/0015 02/22/0018 06/05/0019 03/08/0014 01/03/0020 Page 5 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People DOING BUSINESS END DATE Page 6 of 1464 09/26/2021 Doing Business Search - People 65572 RUSSELL TRUST COMPANY 53596 MOHAWK LTD 68208 ST ANN'S ABH OWNER LLC 136274 NEW YORK CITY CENTER INC. -

Rotch JUL 13 1973

A HOUSING SYSTEM: A STUDY OF AN INDUSTRIALIZED HOUSING SYSTEM IN METAL By: BRUCE M. HAXTON Bachelor of Architecture, University of Minnesota (1969) Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE, ADVANCED STUDIES A t the MA SSACHUSETT S INST ITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May, 1973 Author.............. .. .... .. ...... ... .. ... - Department of Arch itecture Certified by. .. .. .. .. .- . ..-.. ' . .. ... b. ..... -- Thesis Advisor Accepted by.......... -- - Ch i rman, Dew&icr.mental Committee on Graduate Students Rotch JUL 13 1973 May 11, 1973 Dean William Porter School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Dear Dean Porter: In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture, Advanced Studies, I hereby submit this thesis entitled: A HOUSING SYSTEM: A STUDY OF AN INDUSTRIALIZED HOUSING SYSTEM IN METAL. Respectfully, Bruce M. Haxton ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the following people, whose assistance and advice have contributed significantly to the development of this thesis. Waclaw P. Zalewski Professor of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Thesis Advisor Eduardo Catalano Professor of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Aurthor D. Bernhardt Professor of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ezra Ehrenkrantz Visiting Professor Massachusetts Institute of Technology James Bock Executive Vice President Bock Industries Incorporated TABLE OF CONTENTS Ti tle Page Letter of Submittal Acknowledgements Table of Contents Abstract Introduct ion Design Analysis Design Constraints Methodology Design Considerations Areas for Further Study User Requirement Study Market Study Design Study Design Categories Design Components Delivery Components Unit Plans Unit Cluster Plans Details Unit Model Bibliography ABSTRACT A HOUSING- SYSTEM: A STUDY OF AN INDUSTRIALIZED HOUSING SYSTEM IN METAL By BRUCE M. -

Shaw University Bulletin: Inauguration of Robert Prentiss

ARCHIVES WilVBKITY^/ 1M 7/ , cJke Okaw U{yiLversitij BULLETIN Volume VI FEBRUARY, 1937 Number 4 Inauguration of ROBERT PRENTISS DANIEL as THE FIFTH PRESIDENT of SHAW UNIVERSITY Held in The Raleigh Memorial Auditorium Raleigh, North Carolina November 20, 1936 Entered as second-class matter January 25, 1932, at the post office at Raleigh, North Carolina, under the Act of August 2h, 1912. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill http://archive.org/details/shawuniversitybuOOshaw FOREWORD npHE Inaugural Committee is gratified in the support of the alumni and friends of Shaw University upon the occasion of the celebration of the Seventy-first Anniversary of the Founding of the Institution and the Inauguration of the Fifth President. The Committee wishes to express its appreciation to the Shaw Bulletin Committee for the privilege of using the February issue of the Shaw Bulletin as an Inaugural number. J. Francis Price, Chairman Walker H. Quarles, Jr., Secretary Mrs. Martha J. Brown Miss Beulaii Jones Rev. 0. S. Bullock Dr. Max King Miss Mary Burwell Dr. L. E. McCauley W. R. Collins H. Cardrew Perrin Mrs. Julia B. Delaney C. C. Spaulding Charles R. Eason Rev. W. C. Somerville Harry Gil-Smythe Dean Melvin H. Watson Miss Lenora T. Jackson Dean Mary Link Turner Glenwood E. Jones J. W. Yeargin ROBERT PRENTISS DANIEL, A.B., A.M., Ph.D. Dr. Robert P. Daniel Is Installed As President In Impressive Ceremonies A sound program, including a Greetings were extended on behalf course of study which must be func- of the colleges of the Board of Edu- tional to the demands of a dynamic cation of the Northern Baptist Con- society and which will lead to a bet- vention by Dr.