The Concept of Overgrazing and Its Application to Yellowstone's Northern Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is the Most Effective Way to Reduce Population Growth And

Ariana Shapiro TST BOCES New Visions - Ithaca High School Ithaca, NY Kenya, Factor 17 Slowing Population Growth and Urbanization Through Education, Sustainable Agriculture, and Public Policy Initiatives in Kenya Kenya is a richly varied and unique country. From mountains and plains to lowlands and beaches, the diversity within the 224,961 square miles is remarkable. Nestled on the eastern coast of Africa, Kenya is bordered by Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Somalia, and the Indian Ocean. Abundant wildlife and incredible biodiversity make Kenya a favorable tourist attraction, and tourism is the country’s best hard currency earner (BBC). However, tourism only provides jobs for a small segment of the population. 75 percent of Kenyans make their living through agriculture (mostly without using irrigation), on the 8.01 percent of land that is classified as arable (CIA World Factbook). As a result, agricultural activity is very concentrated in the fertile coastal regions and some areas of the highlands. Subsistence farmers grow beans, cassava, potatoes, maize, sorghum, and fruit, and some grow export crops such as tea, coffee, horticulture and pyrethrum (HDR). Overgrazing on the arid plateaus and loss of soil and tree cover in croplands has primed Kenya for recurring droughts followed by floods in the rainy seasons. The increasing environmental degradation has had a profound effect on the people of Kenya by forcing farmers onto smaller plots of land too close to other subsistence farms. Furthermore, inequitable patterns of land ownership and a burgeoning population have influenced many poor farmers to move into urban areas. The rapidity of urbanization has resulted in poorly planned cities that are home to large and unsafe slums. -

Connecting Genetic Diversity and Threat Mapping to Set Conservation Priorities for Juglans Regia L

fevo-08-00171 June 19, 2020 Time: 17:54 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 23 June 2020 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.00171 Diversity Under Threat: Connecting Genetic Diversity and Threat Mapping to Set Conservation Priorities for Juglans regia L. Populations in Central Asia Hannes Gaisberger1,2*, Sylvain Legay3, Christelle Andre3,4, Judy Loo1, Rashid Azimov5, Sagynbek Aaliev6, Farhod Bobokalonov7, Nurullo Mukhsimov8, Chris Kettle1,9 and Barbara Vinceti1 1 Bioversity International, Rome, Italy, 2 Department of Geoinformatics, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria, 3 Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology, Belvaux, Luxembourg, 4 New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand, 5 Bioversity International, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 6 Kyrgyz National Agrarian University named after K. I. Skryabin, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, 7 Institute of Horticulture and Vegetable Growing of Tajik Academy Edited by: of Agricultural Sciences, Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 8 Republican Scientific and Production Center of Ornamental Gardening David Jack Coates, and Forestry, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 9 Department of Environmental System Science, ETH Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), Australia Central Asia is an important center of diversity for common walnut (Juglans regia L.). Reviewed by: We characterized the genetic diversity of 21 wild and cultivated populations across Bilal Habib, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. A complete threat assessment was performed Wildlife Institute of India, -

Land Degradation and the Australian Agricultural Industry

LAND DEGRADATION AND THE AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY Paul Gretton Umme Salma STAFF INFORMATION PAPER 1996 INDUSTRY COMMISSION © Commonwealth of Australia 1996 ISBN This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial usage or sale requires prior written permission from the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Commonwealth Information Services, AGPS, GPO Box 84, Canberra ACT 2601. Enquiries Paul Gretton Industry Commission PO Box 80 BELCONNEN ACT 2616 Phone: (06) 240 3252 Email: [email protected] The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the Industry Commission. Forming the Productivity Commission The Federal Government, as part of its broader microeconomic reform agenda, is merging the Bureau of Industry Economics, the Economic Planning Advisory Commission and the Industry Commission to form the Productivity Commission. The three agencies are now co- located in the Treasury portfolio and amalgamation has begun on an administrative basis. While appropriate arrangements are being finalised, the work program of each of the agencies will continue. The relevant legislation will be introduced soon. This report has been produced by the Industry Commission. CONTENTS Abbreviations v Preface vii Overview -

Overgrazing and Range Degradation in Africa: the Need and the Scope for Government Control of Livestock Numbers

Overgrazing and Range Degradation in Africa: The Need and the Scope for Government Control of Livestock Numbers Lovell S. Jarvis Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics University of California, Davis Paper prepared for presentation at International Livestock Centre for Africa (ILCA) October 1984 Subsequently published in East Africa Economic Review, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1991) Overgrazing and Range Degradation in Africa: The Need and the Scope For Government Control of Livestock Numbers Lovell S. Jarvis1 Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics University of California, Davis Introduction Livestock production has been an integral part of farming systems for hundreds of years in many regions of Africa, but there is little evidence on the herd size or range conditions in the pre- colonial period. The great rinderpest epidemic, 1889 to 1896, severely reduced the cattle population and the human population dependent on it. Some estimate that herds fell to 10% or less of their previous level (Sinclair, 1979). This caused the emergence of forest and brush and the invasion of tsetse in some regions, which further harmed the remaining pastoralists. Since that epidemic the livestock and human populations in most of Africa have grown substantially. By the 1920's, some European observers suggested that systematic overgrazing and range degradation might be occurring as a result of common range, and argued that an alternate land tenure system or external stocking controls were essential to avoid a serious reduction in production. These assertions - whether motivated by concern for herder welfare or eagerness to take over pastoralist land -- have been made repeatedly in subsequent years. -

Late Quaternary Extinctions on California's

Flightless ducks, giant mice and pygmy mammoths: Late Quaternary extinctions on California’s Channel Islands Torben C. Rick, Courtney A. Hofman, Todd J. Braje, Jesu´ s E. Maldonado, T. Scott Sillett, Kevin Danchisko and Jon M. Erlandson Abstract Explanations for the extinction of Late Quaternary megafauna are heavily debated, ranging from human overkill to climate change, disease and extraterrestrial impacts. Synthesis and analysis of Late Quaternary animal extinctions on California’s Channel Islands suggest that, despite supporting Native American populations for some 13,000 years, few mammal, bird or other species are known to have gone extinct during the prehistoric human era, and most of these coexisted with humans for several millennia. Our analysis provides insight into the nature and variability of Quaternary extinctions on islands and a broader context for understanding ancient extinctions in North America. Keywords Megafauna; island ecology; human-environmental interactions; overkill; climate change. Downloaded by [Torben C. Rick] at 03:56 22 February 2012 Introduction In earth’s history there have been five mass extinctions – the Ordovician, Devonian, Permian, Triassic and Cretaceous events – characterized by a loss of over 75 per cent of species in a short geological time period (e.g. 2 million years or less: Barnosky et al. 2011). Although not a mass extinction, one of the most heavily debated extinction events is the Late Quaternary extinction of megafauna, when some two-thirds of large terrestrial mammalian genera (444kg) worldwide went extinct (Barnosky et al. 2004). Explanations for this event include climate change, as the planet went from a glacial to interglacial World Archaeology Vol. -

An Approach for Describing the Effects of Grazing on Soil Quality in Life

sustainability Article An Approach for Describing the Effects of Grazing on Soil Quality in Life-Cycle Assessment Andreas Roesch 1,*, Peter Weisskopf 2, Hansruedi Oberholzer 2, Alain Valsangiacomo 1 and Thomas Nemecek 1 1 Agroscope, LCA Research Group, Reckenholzstrasse 191, CH-8046 Zurich, Switzerland 2 Agroscope, Soil Fertility and Soil Protection Group, Reckenholzstrasse 191, CH-8046 Zurich, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-(0)-58-468-7579 Received: 27 July 2019; Accepted: 30 August 2019; Published: 6 September 2019 Abstract: Describing the impact of farming on soil quality is challenging, because the model should consider changes in the physical, chemical, and biological status of soils. Physical damage to soils through heavy traffic was already analyzed in several life-cycle assessment studies. However, impacts on soil structure from grazing animals were largely ignored, and physically based model approaches to describe these impacts are very rare. In this study, we developed a new modeling approach that is closely related to the stress propagation method generally applied for analyzing compaction caused by off-road vehicles. We tested our new approach for plausibility using a comprehensive multi-year dataset containing detailed information on pasture management of several hundred Swiss dairy farms. Preliminary results showed that the new approach provides plausible outcomes for the two physical soil indicators “macropore volume” and “aggregate stability”. Keywords: soil structure; macropore volume; aggregate stability; compaction; modeling; grazing animal; trampling 1. Introduction Soils are a key component of terrestrial ecosystems and provide multiple ecosystem services to humans, such as provisioning of food, timber, and freshwater. Soil is a natural resource and the basis for agriculture and agricultural food production. -

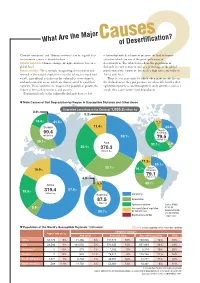

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

CHAPTER 5 HISTORICAL IMPACTS AND CHANGES: BIOTIC RESOURCES AND HUMAN POPULATIONS As described in previous chapters, adverse impacts Turner 1965; Hennessy 1983; Humphrey 1958, 1987; generated by humans on the surface water, vegetation, Johnson and Elson 1977; Neilson 1986; Swetnam 1990; Vale soils, and fauna began with their arrival in the region more 1982, to name just some). Most of these studies examined than 10,000 years ago. In some instances these impacts climate and juniper-grassland savannas, pinyon-juniper and resulting environmental changes were interrelated woodlands, or ponderosa forests, as well as the interrela- with natural phenomena, such as extended droughts and tionships with other ecological factors, notably human- fires. These elements have been discussed in Chapters 2– caused modifications such as grazing, fire suppression, 4, so they will only be summarized in this chapter. fuelwood cutting, and logging. These studies also focused Generally, as Native American populations grew and on changes in the recent past, that is, when Anglo Ameri- technological innovations advanced, these impacts af- cans began colonizing the region in the mid 19th century. fected ever increasingly larger areas, with greater pres- The adverse effects of extended drought on vegetation sures on selected resources. Several events or series of re- were recognized as early as the mid 19th century. In 1857 lated events marked significant changes in impacts on the a geologist with the Lt. Joseph C. Ives military expedition environment. In the late prehistoric period the introduc- to the Colorado River recorded that the lower reaches of tion of the bow-and-arrow, cultigens, and associated ag- upland juniper stands were dead. -

ED128282.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 128 282 SO 009 403 AUTHOR Brown, Lester R.; And Others TITLE Twenty-Two Dimensions of the Population Problem. Worldwatch Paper 5. INSTITUTION Worldwatch Inst., Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY United Nations Fund for Population Activities, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE Mar 76 NOTE 86p. AVAILABLE FROM Worldwatch Institute, 1776 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 ($2.00 paper, 2-10 copies $1.50 each, 11-50 copies $1.25 each, 51 or more copies $1.00 each) EDRS PRICE rIF-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Demography; Developing Nations; Economically Disadvantaged; Energy Conservation; Environmental Influences; Family Planning; Food; *Futures (of Society); *Global Approach; Human Geography; International Programs; Literacy; Natural Resources; Nutrition; *Population Growth; Population Trends; Urbanization; *World Problems ABSTRACT Twenty-two facets of the world population problem are explored. The topics are economic, social, ecological, and political in nature and generally portray the stresses and strains associated with continued population growth in a world inhabited by four billion people. These aspects of the population problem are discussed: literacy, oceanic fisheries, natural recreation areas, pollution, inflation, environmental illnesses, hunger, housing, climate change, overgrazing, crowding, income, urbanization, deforestation, political conflict, minerals, health services, water, unemployment, endangered species, energy, and individual freedom. The authors conclude that analysis of the implications of population growth based on these indicators suggests strongly that the threat posed by uncontrolled growth deserves more attention frc_, national and international leaders than it is presently getting. A bibliography of selected readings is included. (Author/DB) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. -

Organic Agriculture's Role in Combating Desertification

international federation of Organic Agriculture movements Organic Agriculture’s Role in Combating Desertification Organic agriculture is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and a good quality of life for all involved. Organic Agriculture increases the resilience of soils to both water stress and nutrient loss. It contributes to combating desertification by preventing soil erosion and land degradation as well as by helping rehabilitate degraded land. Organic Agriculture helps: • Improve soil fertility by maintaining and building a fertile living soil through frequent organic matter inputs, sustained soil cover, crop rotations and intercropping. Organic Agriculture farming systems integrate crops and animals and can therefore reduce overgrazing and facilitate nutrient recycling on the farm. • Prevent wind and water erosion of the soils through a better, more stable soil structure and texture and through persistent and diversified soil cover and agro-forestry. • Improve water infiltration and retention capacity through high levels of organic matter and permanent soil cover, such as cover crops or mulch, which substantially reduce the amount of water needed for irrigation. • Reduce surface and ground water consumption and subsequent soil salinization through increased water retention capacity, reduction of water evaporation, and the creation of suitable micro- climates in dry areas through diversified organic agro-forestry systems that can attract and retain atmospheric humidity. • Reduce ground and surface water contamination by refraining from the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, thereby protecting the little water available in dry areas from pesticide contamination and nitrate and phosphate leaching. -

Protecting Water Quality from Agricultural Runoff

Protecting Water Quality EPA 841-F-05-001 from AGRICULTURAL R UNOFF Clean Water Is Everybody’s Business he United States has more than T330 million acres of agricultural What Is Nonpoint Source Pollution? land that produce an abundant supply Nonpoint source (NPS) pollution, unlike pollution from point sources of food and other products. Ameri- such as industrial and sewage treatment plants, comes from many can agriculture is noted worldwide for its high productivity, quality, and diffuse sources. Polluted runoff is caused by rainfall or snowmelt efficiency in delivering goods to the moving over and through the ground. As the runoff moves, it picks consumer. When improperly managed up and carries away natural and human-made pollutants, finally however, activities from working farms depositing them into watersheds through lakes, rivers, wetlands, and ranches can affect water quality. coastal waters, and even our underground sources of drinking water. In the 2000 National Water Quality Inventory, states reported that agricul- Did you know that runoff from farms is the leading source of tural nonpoint source (NPS) pollution impairments to surveyed rivers and lakes? is the leading source of water quality impacts on surveyed rivers and lakes, to reduce pollution also increase In addition, other pollutants like the second largest source of impair- productivity and save farmers and fertilizers, pesticides, and heavy metals ments to wetlands, and a major ranchers money in the long run. are often attached to the soil particles contributor to contamination of sur- and wash into the water bodies, causing There are many government programs veyed estuaries and ground water. -

Silvopasture Handbook

Silvopasture: Establishment & management principles for pine forests in the Southeastern United States February 2008 Editor: Jim Hamilton, Ph.D. Production coordinator: Kimberly Stuhr Layout & design: Ryan Dee USDA National Agroforestry Center 1945 N. 38th Street Lincoln, NE 68583–0822 www.unl.edu/nac www.workingtrees.org A partnership of Dedicated to retired U.S. Forest Service researchers Cliff Lewis, Henry Pearson, and Nathan Byrd. Your vision and dedication to improving forest and range management are the strong roots that support the advancement of silvopasture management today. Background This guidebook was created with the hope of improv- ing the value of silvopasture training in two ways: it will be available for use during training sessions and will serve as a concise field companion when planning future silvopastures. The information and principles contained in this initial printing have been reviewed by researchers and natural resource experts. It is anticipated that future versions of the guidebook will incorporate recommendations that result from actual field use and from training sessions. About the editor Jim Hamilton, Ph.D. is a forestry instructor at Haywood Community College in Clyde, NC. He has worked on a number of agroforestry projects in Paraguay, and with silvopasture systems and landowner education as an Extension Agent with Cooperative Extension in North Carolina and Alabama A&M University. Acknowledgments Sid Brantly, NRCS Kentucky Dr. Terry Clason, NRCS Louisiana Dr. Mary Goodman, Auburn University Dr. Joshua Idassi, Tennessee State University George Owens, Florida silvopasturist Dr. Ann Peischel, Tennessee State University James L. Robinson, NRCS Texas Dr. Greg Ruark, U.S. Forest Service Homer Sanchez, NRCS Texas Dr.