A Discoursive Analysis of Champions' Retrospective Attributions : Looking Back and Looking Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Topps Transcendent Tennis Checklist Hall of Fame

TRANSCENDENT ICONS 1 Rod Laver 2 Marat Safin 3 Roger Federer 4 Li Na 5 Jim Courier 6 Andre Agassi 7 David Hall 8 Kim Clijsters 9 Stan Smith 10 Jimmy Connors 11 Amélie Mauresmo 12 Martina Hingis 13 Ivan Lendl 14 Pete Sampras 15 Gustavo Kuerten 16 Stefan Edberg 17 Boris Becker 18 Roy Emerson 19 Yevgeny Kafelnikov 20 Chris Evert 21 Ion Tiriac 22 Charlie Pasarell 23 Michael Stich 24 Manuel Orantes 25 Martina Navratilova 26 Justine Henin 27 Françoise Dürr 28 Cliff Drysdale 29 Yannick Noah 30 Helena Suková 31 Pam Shriver 32 Naomi Osaka 33 Dennis Ralston 34 Michael Chang 35 Mark Woodforde 36 Rosie Casals 37 Virginia Wade 38 Björn Borg 39 Margaret Smith Court 40 Tracy Austin 41 Nancy Richey 42 Nick Bollettieri 43 John Newcombe 44 Gigi Fernández 45 Billie Jean King 46 Pat Rafter 47 Fred Stolle 48 Natasha Zvereva 49 Jan Kodeš 50 Steffi Graf TRANSCENDENT COLLECTION AUTOGRAPHS TCA-AA Andre Agassi TCA-AM Amélie Mauresmo TCA-BB Boris Becker TCA-BBO Björn Borg TCA-BJK Billie Jean King TCA-CD Cliff Drysdale TCA-CE Chris Evert TCA-CP Charlie Pasarell TCA-DH David Hall TCA-DR Dennis Ralston TCA-EG Evonne Goolagong TCA-FD Françoise Dürr TCA-FS Fred Stolle TCA-GF Gigi Fernández TCA-GK Gustavo Kuerten TCA-HS Helena Suková TCA-IL Ivan Lendl TCA-JCO Jim Courier TCA-JH Justine Henin TCA-JIC Jimmy Connors TCA-JK Jan Kodeš TCA-JNE John Newcombe TCA-KC Kim Clijsters TCA-KR Ken Rosewall TCA-LN Li Na TCA-MC Michael Chang TCA-MH Martina Hingis TCA-MN Martina Navratilova TCA-MO Manuel Orantes TCA-MS Michael Stich TCA-MSA Marat Safin TCA-MSC Margaret Smith Court TCA-MW -

Media Guide Template

MOST CHAMPIONSHIP TITLES T O Following are the records for championships achieved in all of the five major events constituting U R I N the U.S. championships since 1881. (Active players are in bold.) N F A O M E MOST TOTAL TITLES, ALL EVENTS N T MEN Name No. Years (first to last title) 1. Bill Tilden 16 1913-29 F G A 2. Richard Sears 13 1881-87 R C O I L T3. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 U I T N T3. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 Y D & T3. Neale Fraser 8 1957-60 S T3. Billy Talbert 8 1942-48 T3. George M. Lott Jr. 8 1928-34 T8. Jack Kramer 7 1940-47 T8. Vincent Richards 7 1918-26 T8. Bill Larned 7 1901-11 A E C V T T8. Holcombe Ward 7 1899-1906 E I N V T I T S I OPEN ERA E & T1. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 S T1. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 T3. Todd Woodbridge 6 1990-2003 T3. Jimmy Connors 6 1974-83 T5. Roger Federer 5 2004-08 T5. Max Mirnyi 5 1998-2013 H I T5. Pete Sampras 5 1990-2002 S T T5. Marty Riessen 5 1969-80 O R Y C H A P M A P S I T O N S R S E T C A O T I R S D T I S C S & R P E L C A O Y R E D R Bill Tilden John McEnroe S * All Open Era records include only titles won in 1968 and beyond 169 WOMEN Name No. -

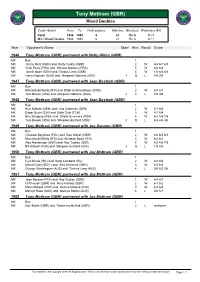

Tony Mottram (GBR) Mixed Doubles

Tony Mottram (GBR) Mixed Doubles Code->Event From To Participations Matches Won/Lost Walkovers W/L Total 1946 1952 6 21 15 / 6 0 / 1 MX->Mixed Doubles 1946 1952 6 21 15 / 6 0 / 1 Year Opponent's Name Seed Rnd Result Score 1946 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Betty Hilton (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Jimmy Hunt (GBR) and Betty Coutts (GBR) 2 W 4/6 6/1 6/3 MX Yvon Petra (FRA) and Simone Mathieu (FRA) 3 W 6/4 6/3 MX Jannik Ipsen (DEN) and Gladys Lines (GBR) 4 W 1/6 6/3 6/4 MX Harry Hopman (AUS) and Margaret Osborne (USA) 1 Q L 4/6 2/6 1947 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Jean Bostock (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Marcello del Bello (ITA) and Bibbi Gullbrandsson (SWE) 2 W 6/3 6/1 MX Tom Brown (USA) and Margaret Osborne (USA) 2 3 L 0/6 3/6 1948 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Jean Bostock (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Kurt Nielsen (DEN) and Lisa Andersen (DEN) 2 W 6/1 6/3 MX Edgar Buchi (SUI) and Edith Sutz (TCH) 3 W 6/1 6/4 MX Eric Sturgess (RSA) and Sheila Summers (RSA) 4 W 6/2 1/6 7/5 MX Tom Brown (USA) and Margaret du Pont (USA) 2 Q L 6/4 4/6 3/6 1949 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Joy Gannon (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Czeslaw Spychala (POL) and Bea Walter (GBR) 2 W 4/6 6/3 6/3 MX Marcello del Bello (ITA) and Annelise Bossi (ITA) 3 W 6/2 6/2 MX Alex Hamburger (GBR) and Kay Tuckey (GBR) 4 W 6/2 4/6 7/5 MX Bill Sidwell (AUS) and Margaret du Pont (USA) 2 Q L 1/6 4/6 1950 Tony Mottram (GBR) partnered with Joy Mottram (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Cyril Kemp (IRL) and Betty Lombard (IRL) 2 W 6/2 6/4 MX Marcel Coen (EGY) and Alex McKelvie (GBR) 3 W 6/3 6/4 MX George Worthington (AUS) and -

Reagan Presses Dobrynin to Get Arms Talks Going

Manalapan dedicates its new Recreation Center, B1 \ GREATER RED BANK Ahead from the start EATONTOWN South to the border #£ vPU'LXKi'jQk LONG BRANCH Jackson, thousands tZJnwrikJkJfk Andretti captures march for peace Today's Forecast: 'Ir^ !• 1 U.S. Grand Prix. Sunny, chance of showers Page A3 Pa e B2 Complete weather on A2 i^^J n 9 ' #3 Hffill The Daily Register VOL. 106 NO. 301W8 YOU\zr\i IRD HOMETOWuniiCTnuiMN NEWSPAPEMCIA/CDADCDR ^SINC^^NM^CE 187IQ-?8D ^~—^^ MONinAMONDAYY , JilJULl Y 92 , 1Q198P 4 . <«,CFNTs Reagan presses Dobrynin to get arms talks going WASHINGTON (AP) - Presi- dent Reagan, trying to entice the Kremlin to discuss resuming nu- clear arms talks, apparently used a White House barbecue to press his case with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly F. Dobrynin, but both sides remained tight-lipped about what was said. Dobrynin, the dean of the diplomatic corps, was seated be- tween Reagan and Secretary of State George P. Shultz during the dinner last night in honor of the diplomatic corps in the East Room Despite the presence of other guests at the president's round table, the the three men engaged in animated conversation throughout the meal, laughing often Earlier, while Reagan was greet- ing his guests outdoors on a hot, muggy night, Shulti and Dobrynin huddled together in a secluded comer of the Green Room, away from tbe other 380 guests, deep in DINNER TALK — President Reagan, right, chats with Soviet private conversation. Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin during a barbecue for members ot WALKING IN THE RAIN - Yesterday was not the umbrella, takes time out to the surf smash up The talk looked serious and ideal day for taking a stroll on the Long Branch against the pier and the beach. -

Jimmy Arias: Ranked Number 5 in the World Now Wows the World As ESPN Commentator

Jimmy Arias: Ranked Number 5 in the World Now Wows the World as ESPN Commentator immy Arias and I have At what point did you real- effusive with his praise, and I loved that, a lot in common. We ize you had extraordinary tal- and it spurred me on to work hard, be- Jboth grew up play- ent well beyond Buffalo? cause I had never heard that before. ing at the Buffalo Tennis I think around 9 years old. Center in the 1970’s. We I started playing in the Eastern Were you homesick for Buffalo both played a lot of tour- tournaments 12-and-unders early on, or did you feel like you made naments. We’re both Buf- and finished top 5 which got the right move to leave for Longboat falo Bills fans with dark me to the nationals. There was Key? hair parted on the side. no one else my age or my size The first year was rough. I was just Alright. Jimmy Arias winning matches, so I think at 13 and I didn’t really have a place to stay, and I have nothing in com- that point I realized ‘Hey, I’m not there weren’t other kids there yet. There mon. I knew of him when he bad.’ I had a different game than were two local kids there and we didn’t was 7 years old. He’d fill-in as a everyone else, a little more powerful, get along because I sort of came in and substitute in my father’s tennis group, and so I already felt like I was in control when I stole their thunder. -

10/15/2010 City Manager Report

Office of the City Manager TO: Mayor and Council FROM: Mark A. Coronado, Interim City Manager DATE: October 15, 2010 SUBJECT: Issues Update 3RD ANNUAL CANCER TREATMENT CENTERS OF AMERICA TENNIS CHAMPIONSHIPS. The 3rd Annual Cancer Treatment Centers of America Tennis Championships, presented by Sanderson Volvo kicks off Wednesday, October 20 at 7pm. The 5-day event features tennis greats John McEnroe, Michael Chang, Jim Courier, Wayne Ferreira, Mark Philippoussis, Jimmy Arias, Aaron Krickstein and Jeff Tarango. Enjoy mixed doubles on Saturday with Anna Kournikova and Ashley Harkleroad. The schedule follows. TOURNAMENT MATCH SCHEDULE Session 1 Wednesday, Oct 7pm Match A: Philippoussis vs. Krickstein 20 Match B: Courier vs. Tarango Session 2 Thursday, Oct 21 7pm Match A: Chang vs. Arias Match B: McEnroe vs. Ferreira Session 3 Friday, Oct 22 2pm Match A: Philippoussis vs. Arias Match B: Chang vs. Krickstein Session 4 Friday, Oct 22 7pm Match A: Courier vs. Ferreira Match B: McEnroe vs. Tarango Session 5 Saturday, Oct 23 Noon Match A: Arias vs. Krickstein Match B: Kournikova & Tarango vs. Harkleroad & Ferreira Match C: Chang vs. Philippoussis Session 6 Saturday, Oct 23 6pm Match A: Courier vs. McEnroe Mixed Doubles: Kournikova & Arias vs. Harkleroad & Krickstein Match B: Ferreira vs. Tarango Session 7 Sunday, Oct 24 Noon 3rd Place Match Championship Match Mayor & Council -2- October 15, 2010 NATIONAL RECOGNITION FOR SURPRISE The Communications Department’s Surprise 11 placed in the top ranks of a nationwide video competition recognizing community outreach. The documentary production, “Surprise: a History in Progress,” placed second nationally at the annual awards competition of the National Association of Broadcast Officers and Administrators in Washington, DC. -

ADCTF Annual Report 2018

THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP 2018 TENNIS FOUNDATION ANNUAL ABN 90 004 905 060 Approved by Tennis Australia REPORT THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION Annual Report 2018 1 THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION Annual Report 2018 2 THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION ABN 90 004 905 060 NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Notice is hereby given that the forty-seventh Annual General Meeting of The Australian Davis Cup Tennis Foundation will be held in the Clubhouse of the Royal South Yarra Lawn Tennis Club, Williams Road North, Toorak, on Tuesday 27th November 2018 at 8.00pm. BUSINESS 1. To receive, consider and if thought fit, to adopt the Directors' Report, the Directors' Declaration, the Statement of Financial Position as at 30th June 2018, the Statement of Comprehensive Income, the Statement of Cash Flows and the Statement of Changes in Equity for the year ended 30th June 2018 together with the Auditor's Report thereon. 2. To elect four (4) Directors to replace those persons retiring in accordance with the Constitution. 3. To transact any other business that, being lawfully brought forward, is accepted by the Chairman for discussion. BY ORDER OF THE BOARD Alan J Cobb. Honorary Secretary. Melbourne, 1st October, 2018 THE AUSTRALIAN DAVIS CUP TENNIS FOUNDATION Annual Report 2018 1 PROXIES A Member entitled to attend and vote at the Meeting is entitled to appoint one proxy to attend and vote in his or her stead. A proxy must be a Member. The form for the appointment of a proxy is available on application to the Honorary Secretary and must be lodged with the Honorary Secretary no later than 48 hours prior to the scheduled commencement of the Meeting. -

Jnlajmjj National League, Organ- and Parke’S White- Top New Britain

U. S. Davis Cup Aces McKinney's Hook Shots Amaze Miss on Final Shot Unbeaten Cage Lot Ordered to Fans Watching Caps Win Again to 11 Teams Drop ThoM who visited mine’s Arena The Caps ran up a 17-10 nrst- Cut last night to witness the Washing- period lead and never were headed. the Associated Press Robs Bowler of Tie By ton Capitols’ 69-57 victory over the It was the 18th straight home- NEW YORK, Jan. 30.—Villa- Australian Tour Boston Celtics went away wonder- court win for the locals, whose six nova’s 45-to-42 victory over Army t §y th» Associated Press ing how Bones McKinney perfected losses have been suffered on the thinned to 11 the num- bis impossible hook shot. road. Pin Lead yesterday SYDNEY. Jan. 30.—The United s*«"frigly For Star ber of unbeaten college basket ball Bones kept the fans in near hys- Bob Gantt, an old-time school- States Lawn Tennis Association has By Rod Thomas teams in the country. The eleven: terics as he paced the Caps’ attack mate and neighbor of McKinney's, W. L. recalled Gardnar Mulloy, Bill Tal- with 22 points, only 4 of which were who starred for Duke in 1943, made With a bit of luck, young John his debut last with Kirkville (Mo.) Teachers.. 18 0 bert $nd Tom Brown, three mem- picked up from the charity stripe. night the Caps. Parise of the Takoma Duckpin As- 0 Ks book shot, thrown with Gantt missed the only free throw Seton Hall (N. -

2020 Yearbook

-2020- CONTENTS 03. 12. Chair’s Message 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 2 & Tier 3 04. 13. 2020 Inductees Vale 06. 14. 2020 Legend of Australian Sport Sport Australia Hall of Fame Legends 08. 15. The Don Award 2020 Sport Australia Hall of Fame Members 10. 16. 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 1 Partner & Sponsors 04. 06. 08. 10. Picture credits: ASBK, Delly Carr/Swimming Australia, European Judo Union, FIBA, Getty Images, Golf Australia, Jon Hewson, Jordan Riddle Photography, Rugby Australia, OIS, OWIA Hocking, Rowing Australia, Sean Harlen, Sean McParland, SportsPics CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2020 has been a year like no other. of Australian Sport. Again, we pivoted and The bushfires and COVID-19 have been major delivered a virtual event. disrupters and I’m proud of the way our team has been able to adapt to new and challenging Our Scholarship & Mentoring Program has working conditions. expanded from five to 32 Scholarships. Six Tier 1 recipients have been aligned with a Most impressive was their ability to transition Member as their Mentor and I recognise these our Induction and Awards Program to prime inspirational partnerships. Ten Tier 2 recipients time, free-to-air television. The 2020 SAHOF and 16 Tier 3 recipients make this program one Program aired nationally on 7mate reaching of the finest in the land. over 136,000 viewers. Although we could not celebrate in person, the Seven Network The Melbourne Cricket Club is to be assembled a treasure trove of Australian congratulated on the award-winning Australian sporting greatness. Sports Museum. Our new SAHOF exhibition is outstanding and I encourage all Members and There is no greater roll call of Australian sport Australian sports fans to make sure they visit stars than the Sport Australia Hall of Fame. -

Doubles Final (Seed)

2016 ATP TOURNAMENT & GRAND SLAM FINALS START DAY TOURNAMENT SINGLES FINAL (SEED) DOUBLES FINAL (SEED) 4-Jan Brisbane International presented by Suncorp (H) Brisbane $404780 4 Milos Raonic d. 2 Roger Federer 6-4 6-4 2 Kontinen-Peers d. WC Duckworth-Guccione 7-6 (4) 6-1 4-Jan Aircel Chennai Open (H) Chennai $425535 1 Stan Wawrinka d. 8 Borna Coric 6-3 7-5 3 Marach-F Martin d. Krajicek-Paire 6-3 7-5 4-Jan Qatar ExxonMobil Open (H) Doha $1189605 1 Novak Djokovic d. 1 Rafael Nadal 6-1 6-2 3 Lopez-Lopez d. 4 Petzschner-Peya 6-4 6-3 11-Jan ASB Classic (H) Auckland $463520 8 Roberto Bautista Agut d. Jack Sock 6-1 1-0 RET Pavic-Venus d. 4 Butorac-Lipsky 7-5 6-4 11-Jan Apia International Sydney (H) Sydney $404780 3 Viktor Troicki d. 4 Grigor Dimitrov 2-6 6-1 7-6 (7) J Murray-Soares d. 4 Bopanna-Mergea 6-3 7-6 (6) 18-Jan Australian Open (H) Melbourne A$19703000 1 Novak Djokovic d. 2 Andy Murray 6-1 7-5 7-6 (3) 7 J Murray-Soares d. Nestor-Stepanek 2-6 6-4 7-5 1-Feb Open Sud de France (IH) Montpellier €463520 1 Richard Gasquet d. 3 Paul-Henri Mathieu 7-5 6-4 2 Pavic-Venus d. WC Zverev-Zverev 7-5 7-6 (4) 1-Feb Ecuador Open Quito (C) Quito $463520 5 Victor Estrella Burgos d. 2 Thomaz Bellucci 4-6 7-6 (5) 6-2 Carreño Busta-Duran d. -

Tennis in Colorado

Year 32, Issue 5 The Official Publication OfT ennis Lovers Est. 1976 WINTER 08/09 FALL 2008 From what we get, we can make a living; what we give, however, makes a life. Arthur Ashe Celebrating the true heroes of tennis USTA COLORADO Gates Tennis Center 3300 E Bayaud Ave, Suite 201 Denver, CO 80209 303.695.4116 PAG E 2 COLORADO TENNIS WINTER 2008/2009 VOTED THE #3 BEST TENNIS RESORT IN AMERICA BY TENNIS MAGAZINE TENNIS CAMPS AT THE BROA DMOOR The Broadmoor Staff has been rated as the #1 teaching staff in the country by Tennis Magazine for eight years running. Join us for one of our award-winning camps this winter or spring on our newly renovated courts! If weather is inclement, camps are held in our indoor heated bubble through April. Fall & Winter Camp Dates: Date: Camp Level: Dec 28-30 Professional Staff Camp for 3.0-4.0’s Mixed Doubles “New Year’s Weekend” Feb 13-15 3.5 – 4.0 Mixed Doubles “Valentine’s Weekend” Feb 20-22 3.5 – 4.0 Women’s w/ “Mental Toughness” Clinic Mar 13-15 3.5 – 4.0 Coed Mar 27-29 3.0 – 4.0 Coed “Broadmoor’s Weekend of Jazz” May 22-24 3.5 – 4.0 Coed “Dennis Ralston Premier” Camp May 29 – 31 All Levels “Dennis Ralston Premier” Camp Tennis Camps Include: • 4:1 student/pro (players are grouped with others of their level) • Camp tennis bag, notebook and gift • Intensive instruction and supervised match play • Complimentary court time and match arranging • Special package rates with luxurious Broadmoor room included or commuter rate available SPRING TEAM CAMPS Plan your tennis team getaway to The Broadmoor now! These three-day, two-night weekends are still available for a private team camp: January 9 – 11, April 10 – 12, May 1 – 3. -

2017 Media Kit Content Overview

2017 Media Kit Content Overview As the premier provider of tennis lifestyle content and pro game coverage, The Tennis Media Company produces Tennis Magazine, Tennis.com and Baseline. Appealing to both the fan and the player, each platform offers a comprehensive and authoritative look at one of the nation’s most popular sports. OUR EDITORIAL COVERAGE INCLUDES Pro Game & Players Gear, Apparel & Footwear Health, Fitness & Nutrition Instruction Lifestyle & Travel History & Heritage For more information, please contact Associate Publisher, Adam Milner at [email protected] or 646.783.1406 Staff Writers & Expert Contributors CHRIS EVERT Partner & Contributor One of the most prominent female athletes of our time, Chris Evert won 18 Grand Slam titles during her Hall of Fame Career. Chris contributes a regular column in Tennis Magazine, as well as instructional videos and feature stories on Tennis.com and Baseline. PETER BODO Senior Writer/Columnist A preeminent voice in tennis for more than four decades, Peter Bodo began his career in an early 1970s edition of Tennis Magazine. Since then, he has written hundreds of essays and more than a half a dozen books, including “The Courts of Babylon.” Peter has covered every major tennis tournament multiple times and is a two-time winner of the WTA Writer of the Year Award. STEPHEN TIGNOR Senior Writer/Columnist Stephen Tignor has covered the sport for 15+ years and currently writes a daily blog on Tennis.com in addition to numerous features and cover stories in both Tennis Magazine and Baseline. He is the author of the 2011 critically acclaimed book “High Strung,” in which The Associated Press reviewed his approach of “descriptive prose and flair for dramatic writing” as a “true page turner.” NICK BOLLETTIERI Instruction Consultant An influential legend, Nick Bollettieri has coached 10 players that have gone on to rank No.