Robert Mitchum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2Friday 1Thursday 3Saturday 4Sunday 5Monday 6Tuesday 7Wednesday 8Thursday 9Friday 10Saturday

JULY 2021 1THURSDAY 2FRIDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: TCM BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE: WILLIAM WYLER KEEPING THE KIDS BUSY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: SELVIS FRIDAY NIGHT NEO-NOIR Seeing Double 8:00 PM Harper (‘66) 8:00 PM Kissin’ Cousins (‘64) 10:15 PM Point Blank (‘67) 10:00 PM Double Trouble (‘67) 12:00 AM Warning Shot (‘67) 12:00 AM Clambake (‘67) 2:00 AM Live A Little, Love a Little (‘68) 3SATURDAY 4SUNDAY DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME THEME: SATURDAY MATINEE HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY PRIMETIME THEME: PRIMETIME THEME: GABLE GOES WEST HAPPY INDEPENDENCE DAY 8:00 PM The Misfits (‘61) 8:00 PM Yankee Doodle Dandy (‘42) 10:15 PM The Tall Men (‘55) 10:15 PM 1776 (‘72) JULY JailhouseThes Stranger’s Rock(‘57) Return (‘33) S STAR OF THE MONTH: Elvis 5MONDAY 6TUESDAY 7WEDNESDAY P TCM SPOTLIGHT: Star Signs DAYTIME THEME: DAYTIME AND PRIMETIME THEME(S): DAYTIME THEME: MEET CUTES DAYTIME THEME: TY HARDIN TCM PREMIERE PRIMETIME THEME: SOMETHING ON THE SIDE PRIMETIME THEME: DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA PRIMETIME THEME: THE GREAT AMERICAN MIDDLE TWITTER EVENTS 8:00 PM The Bonfire of the Vanities (‘90) PSTAR SIGNS Small Town Dramas NOT AVAILABLE IN CANADA 10:15 PM Obsession (‘76) Fire Signs 8:00 PM Peyton Place (‘57) 12:00 AM Sisters (‘72) 8:00 PM The Cincinnati Kid (‘65) 10:45 PM Picnic (‘55) 1:45 AM Blow Out (‘81) (Steeve McQueen – Aries) 12:45 AM East of Eden (‘55) 4:00 AM Body Double (‘84) 10:00 PM The Long Long Trailer (‘59) 3:00 AM Kings Row (‘42) (Lucille Ball – Leo) 5:15 AM Our Town (‘40) 12:00 AM The Bad and the Beautiful (‘52) (Kirk Douglas–Sagittarius) -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

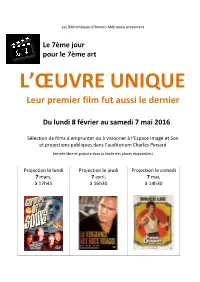

L'œuvre Unique

Les Bibliothèques d’Amiens Métropole présentent Le 7ème jour pour le 7ème art L’ŒUVRE UNIQUE Leur premier film fut aussi le dernier Du lundi 8 février au samedi 7 mai 2016 Sélection de films à emprunter ou à visionner à l’Espace Image et Son et projections publiques dans l’auditorium Charles Pinsard (entrée libre et gratuite dans la limite des places disponibles) Projection le lundi Projection le jeudi Projection le samedi 7 mars, 7 avril, 7 mai, à 17h45 à 16h30 à 14h30 Un seul film à la réalisation, et puis s'en va... Par envie ou par défi, nombreux sont ceux qui réalisent un premier...et parfois un unique film. Expérience douloureuse, difficultés financières, désintérêt, désir de revenir à son métier d'origine, échec commercial, mort prématurée, raisons politiques, circonstances historiques... Ce ne sont pas les explications qui manquent. Voici quelques exemples connus, d'autres beaucoup moins. Quartet / Dustin Hoffman (2013) Avec Maggie Smith, Tom Courtenay, Billy Connolly… A 76 ans, Dustin Hoffman s'est enfin lancé. L'homme aux deux Oscars, l'acteur à la filmographie éblouissante, est passé derrière la caméra pour raconter l'histoire de quatre anciennes gloires anglaises de l'opéra, retirées dans une maison de retraite pour artiste. Un "Quartet" qui va accepter de rechanter d'une même voix malgré les brouilles du passé, pour sauver l'établissement. Rendez-vous l'été prochain / Philip Seymour Hoffman (2010) Avec Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Ryan, John Ortiz… Découvrir l’unique film de Philip Seymour Hoffman réalisateur, après sa mort, à 46 ans, a quelque chose de troublant. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

Monday 25 July 2016, London. Ahead of Kirk Douglas' 100Th Birthday This

Monday 25 July 2016, London. Ahead of Kirk Douglas’ 100th birthday this December, BFI Southbank pay tribute to this major Hollywood star with a season of 20 of his greatest films, running from 1 September – 4 October 2016. Over the course of his sixty year career, Douglas became known for playing iconic action heroes, and worked with the some of the greatest Hollywood directors of the 1940s and 1950s including Billy Wilder, Howard Hawks, Vincente Minnelli and Stanley Kubrick. Films being screened during the season will include musical drama Young Man with a Horn (Michael Curtiz, 1949) alongside Lauren Bacall and Doris Day, Stanley Kubrick’s epic Spartacus (1960), Champion (Mark Robson, 1949) for which he received the first of three Oscar® nominations for Best Actor, and the sci- fi family favourite 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Richard Fleischer, 1954). The season will kick off with a special discussion event Kirk Douglas: The Movies, The Muscles, The Dimple; this event will see a panel of film scholars examine Douglas’ performances and star persona, and explore his particular brand of Hollywood masculinity. Also included in the season will be a screening of Seven Days in May (John Frankenheimer, 1964) which Douglas starred in opposite Ava Gardner; the screening will be introduced by English Heritage who will unveil a new blue plaque in honour of Ava Gardner at her former Knightsbridge home later this year. Born Issur Danielovich into a poor immigrant family in New York State, Kirk Douglas began his path to acting success on a special scholarship at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City, where he met Betty Joan Perske (later to become better known as Lauren Bacall), who would play an important role in helping to launch his film career. -

Council of Europe —~—— ---Conseil De L

COUNCIL OF EUROPE —~—— ---------------- CONSEIL DE L’EUROPE Strasbourg, 19th May 1967 DPC/CORC(66)5Final COE042297 SMALL COMMITTEE OF RESEARCH WORKERS "Influence of the cinema on juvenile delinquency" Film censorship codes in Europe by C. BREMOND The following notes does not purport to give an exhaustive picture of the film censorship codes in force in the member countries of the Council of Europe. Despite the wealth of valuable information assembled (l) our knowledge of such codes is still incomplete; for if we rely solely on official texts defining the principles which are to guide censorship decisions, these seem to us, as a rule, too broad to allow a research study to "bite"on. Moreover, we know from the replies themselves that there is frequently a considerable gap between the letter of such rules and the spirit in which they applied. On the other hand, if we attempt to deduce the practice of - censorship bodies by analysing the decisions reached in particular casus, we come up against the opposite difficulty and find that the considerations which dispose the (l) Cyclo-styled documents containing replies by member States to the Council of Europe Questionnaire. 6065 05.2/56.37 censors to leniency in one case and to severity in another are complex., so confused, often so largely intuitive as seemingly to defy analysis and hence any attempt to generalise the two types of difficulty are in fact inter-connected: the reason why official regulations are couched in general terms lies in the difficulty of generalising the grounds on which decisions are in fact taken. -

Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated

Archives & Special Collections UA1983.25, UA1995.20 Elizabeth A. Schor Collection Dates: 1909-1995, Undated Creator: Schor, Elizabeth Extent: 15 linear feet Level of description: Folder Processor & date: Matthew Norgard, June 2017 Administration Information Restrictions: None Copyright: Consult archivist for information Citation: Loyola University Chicago. Archives & Special Collections. Elizabeth A. Schor Collection, 1909-1995, Undated. Box #, Folder #. Provenance: The collection was donated by Elizabeth A. Schor in 1983 and 1995. Separations: None See Also: Melville Steinfels, Martin J. Svaglic, PhD, papers, Carrigan Collection, McEnany collection, Autograph Collection, Kunis Collection, Stagebill Collection, Geary Collection, Anderson Collection, Biographical Sketch Elizabeth A. Schor was a staff member at the Cudahy Library at Loyola University Chicago before retiring. Scope and Content The Elizabeth A. Schor Collection consists of 15 linear feet spanning the years 1909- 1995 and includes playbills, catalogues, newspapers, pamphlets, and an advertisement for a ticket office, art shows, and films. Playbills are from theatres from around the world but the majority of the collection comes from Chicago and New York. Other playbills are from Venice, London, Mexico City and Canada. Languages found in the collection include English, Spanish, and Italian. Series are arranged alphabetically by city and venue. The performances are then arranged within the venues chronologically and finally alphabetically if a venue hosted multiple productions within a given year. Series Series 1: Chicago and Illinois 1909-1995, Undated. Boxes 1-13 This series contains playbills and a theatre guide from musicals, plays and symphony performances from Chicago and other cities in Illinois. Cities include Evanston, Peoria, Lake Forest, Arlington Heights, and Lincolnshire. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Anthony Hopkins Knows How to Play It

CP HOPKINS_AUG_V 7/11/07 3:05 PM Page 28 CELEBRITY PLAYGROUND BY MICHAEL SHULMAN Magical Realism CineVegas Honoree Anthony Hopkins Knows How to Play It n Friday, June 15th, Academy the script, did you have any idea just Award-winning actor Sir Antho- how integral a part of the Zeitgeist that O ny Hopkins—in Las Vegas to role would become? receive the 2007 Marquee Award from the I had a hunch. I don’t know why, because CineVegas Film Festival—sat down at the I’m not Hannibal Lecter. I just had this Palms Casino Resort for an insightful tête- uncanny feeling as an actor. à-tête with Vegas’ very own pop-culture So something inside of you just said…. pundit, Michael Shulman. Actors are supposed to have this highly developed sense of intuition. Some actors ANTHONY HOPKINS: Hello. Call me Tony, act from their heads, but I tend to act…. please. From the gut? VEGAS: Well, then, welcome to fabulous Yeah. I had a sense that this was going to Las Vegas, Tony. And I know I’m most be one of those parts that give me a likely mispronouncing this, but cymru whole different look at the movies. And I am byth [a Welsh motto meaning ‘Wales knew how to play it. forever’]. Before that, you were leaving Hollywood Cymru am byth [pronouncing it cumree and going back to the stage, no? um bithe]. I’d gone back to London. And it’s interest- In speaking of your film Slipstream, you ing, but I’m sure you know the film The commented on your fascination with Third Man [1949 Oscar and Palme d’Or time, saying, ‘If there is a god, that god is winner starring Joseph Cotten and Orson actually time.’ Could you expound a bit? Welles]? It’s this incredible film in which I’ve always been interested in the mystery you hear about the main character for 15 of time, because you can never grasp minutes before you ever see him. -

Bad Lawyers in the Movies

Nova Law Review Volume 24, Issue 2 2000 Article 3 Bad Lawyers in the Movies Michael Asimow∗ ∗ Copyright c 2000 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Asimow: Bad Lawyers in the Movies Bad Lawyers In The Movies Michael Asimow* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 533 I. THE POPULAR PERCEPTION OF LAWYERS ..................................... 536 El. DOES POPULAR LEGAL CULTURE FOLLOW OR LEAD PUBLIC OPINION ABOUT LAWYERS? ......................................................... 549 A. PopularCulture as a Followerof Public Opinion ................ 549 B. PopularCulture as a Leader of Public Opinion-The Relevant Interpretive Community .......................................... 550 C. The CultivationEffect ............................................................ 553 D. Lawyer Portrayalson Television as Compared to Movies ....556 IV. PORTRAYALS OF LAWYERS IN THE MOVIES .................................. 561 A. Methodological Issues ........................................................... 562 B. Movie lawyers: 1929-1969................................................... 569 C. Movie lawyers: the 1970s ..................................................... 576 D. Movie lawyers: 1980s and 1990s.......................................... 576 1. Lawyers as Bad People ..................................................... 578 2. Lawyers as Bad Professionals .......................................... -

The Making of the Graduate

2/12/2018 The Making of "The Graduate" | Vanity Fair F R O M T H E M A G A Z I N E Here’s to You, Mr. Nichols: The Making of The Graduate Almost from the start, Mike Nichols knew that Anne Bancroft should play the seductive Mrs. Robinson. But the young film director surprised himself, as well as everyone else, with his choice for The Graduate’s misfit hero, Benjamin Braddock: not Robert Redford, who’d wanted the role, but a little-known Jewish stage actor, Dustin Hoffman. From producer Lawrence Turman’s $1,000 option of a minor novel in 1964 to the movie’s out-of-left- field triumph three years later, Sam Kashner recalls a breakout film that literally changed the face of Hollywood. by S A M K A S H N E R M A R C H 2 0 0 8 https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2008/03/graduate200803 1/23 2/12/2018 The Making of "The Graduate" | Vanity Fair Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft in a publicity still for The Graduate. Photographs by Bob Willoughby. Any good movie is filled with secrets. —Mike Nichols magine a movie called The Graduate. It stars Robert Redford as Benjamin Braddock, the blond and bronzed, newly minted college graduate adrift in his parents’ opulent home in Beverly Hills. And Candice Bergen as his girlfriend, the overprotected Elaine Robinson. Ava Gardner plays the predatory Mrs. Robinson, the desperate housewife and mother who ensnares Benjamin. Gene Hackman is her cuckolded husband. It Inearly happened that way. -

American Moviemakers: Directed by Vincente Minnelli

American MovieMakers "AMERICAN MOVIEMAKERS: DIRECTED BY VINCENTE MINNELLI December 15, 1989 - January 28, 1990 All films directed by Vincente Minnelli, produced by MGM Studios, and Courtesy of Turner Entertainment, Co., except where otherwise noted. Cabin in the Sky, 1943. With Ethel Waters, Eddie "Rochester" Anderson, Lena Home, Louis Armstrong. 96 minutes. I Pood It, 1943. With Red Skelton, Eleanor Powell, Lena Home. 101 minutes. Meet Me in St. Louis, 1944. With Judy Garland, Margaret O'Brien, Mary Astor, Lucille Bremer. 113 minutes. The Clock, 1945. With Judy Garland, Robert Walker, James Gleason. 90 minutes. Yolanda and the Thief, 1945. With Fred Astaire, Lucille Bremer, Frank Morgan, Mildred Natwick. 110 minutes Ziegfeld Follies, 1944, released 1946. With Fred Astaire, Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Lucille Bremer. 110 minutes Undercurrent, 1946. With Katharine Hepburn, Robert Taylor, Robert Mitchum. 116 minutes The Pirate, 1948. With Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Walter Slezak, Gladys Cooper. 102 minutes Madame Bovary, 1949. With Jennifer Jones, James Mason, Van Heflin, Louis Jourdan. 115 minutes Father of the Bride, 1950. With Spencer Tracy, Joan Bennett, Elizabeth Taylor. 93 minutes Father's Little Dividend, 1951. With Spencer Tracy, Joan Bennett, Elizabeth Taylor. 82 minutes An American in Paris, 1951. With Gene Kelly, Leslie Caron, Oscar Levant, Nina Foch, Georges Guetary. 113 minutes -more- The Museum of Modern Art - 2 - The Bad and the Beautiful, 1953. With Lana Turner, Kirk Douglas, Walter Pidgeon, Dick Powell, Gloria Grahame, Gilbert Roland. 118 minutes The Story of Three Loves, 1953. "Mademoiselle" sequence. With Ethel Barrymore, Leslie Caron, Farley Granger, Ricky Nelson, Zsa Zsa Gabor. 122 minutes The Band Wagon, 1953.