Report on Citizenship Law:Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of the Legislature in Upholding the Rule of Law in Bangladesh Md

The Role of the Legislature in Upholding the Rule of Law in Bangladesh Md. Mostafijur Rahman 1 Abstract : In the contemporary global politics the rule of law is considered as the pre-requisite for better democracy, socio-economic development and good govern- ance. It is also essential in the creation and advancement of citizens’ rights of a civilized society and being considered for solving many problems in the developing country. The foremost role of the legislature-as second branch of government to recognise the rights of citizens and to assure the rule of law prevails. In order to achieve this goal the legislature among the pillars of a state should be constructive, effective, functional and meaningful. Although the rule of law is the basic feature of the constitution of Bangladesh the current state of the rule of law is a frustration because, almost in all cases, it does not favour the rights of the common people. Under the circumstances, the existence of the rule of law without an effective parlia- ment is conceivable. The main purpose of this study is to examine to what extent the parliament plays a role in upholding the rule of law in Bangladesh and conclude with pragmatic way forward accordingly. Keywords: Rule of law, principles of law, citizens’ rights, legislature, electoral procedure, legislative process. Introduction The ‘rule of law’ is opposed to ‘rule of man’. The term ‘rule of law’ is derived from the French phrase la Principe de legalite (the princi- ple of legality) which refers to a government based on principles of law and not of men. -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

70+6'& 0#6+105 %4% %QPXGPVKQPQPVJG Distr. 4KIJVUQHVJG%JKN GENERAL CRC/C/65/Add.22 14 March 2003 Original: ENGLISH COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION Second periodic reports of States parties due in 1997 BANGLADESH* [12 June 2001] * For the initial report submitted by the Government of Bangladesh, see CRC/C/3/Add.38 and 49; for its consideration by the Committee, see documents CRC/C/SR.380-382 and CRC/C/15/Add.74. GE.03-40776 (E) 120503 CRC/C/65/Add.22 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. BACKGROUND ......................................................................... 1 - 5 3 II. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 6 - 16 4 A. Land and people .................................................................. 7 - 10 4 B. General legal framework .................................................... 11 - 16 5 III. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION ........................ 17 - 408 6 A. General measures of implementation ................................. 17 - 44 6 B. Definition of the child ......................................................... 45 - 47 13 C. General principles ............................................................... 48 - 68 14 D. Civil rights and freedoms ................................................... 69 - 112 18 E. Family environment and alternative care ........................... 113 - 152 25 F. Basic health and welfare .................................................... -

Memo No: 37.00.0000.082.22.0005.16.1551(100), Date: 24 December 2019

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Ministry of Education Secondary and Higher Education Division Administration and Establishment Wing www.shed.gov.bd Memo No: 37.00.0000.082.22.0005.16.1551(100), Date: 24 December 2019 Sub: International Mother Language Award Guidelines 2019 Following the decision taken by International Mother Language Institute regarding the conferment of awards, the International Mother Language Award Guidelines 2019 is hereby notified for the intimation of all concerned; and as per the International Mother Language Award Guidelines 2019, awards would be conferred in recognition of the outstanding contribution for the protection and promotion, culture, practice and research of mother languages in Bangladesh and throughout the world. 1.0 Short title and jurisdiction: 1.1 The guidelines shall be entitled as the International Mother Language Award Guidelines 2019. 1.2 The jurisdiction of the guidelines shall be Bangladesh and the member states of UNESCO. 1.3 The guidelines shall come into force forthwith. 2.0 Unless there is anything repugnant in the subject or context, the following shall be defined by these guidelines: 2.1 “Institute” means “International Mother Language Institute” established under the section 3 of ‘International Mother Language Institute Act - 2010’. 2.2 “International Mother Language Award” means the ‘prize’ conferred in favour of the native and foreign individuals by International Mother Language Institute under these guidelines in recognition of the outstanding contribution for the protection, promotion, culture, practice and research of mother languages. 2.3 “Certificate of Appreciation” means the “Certificate of Appreciation” to be conferred in favour of the individual or institution/agency by Institute. -

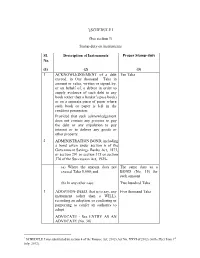

[SCHEDULE I (See Section 3) Stamp Duty on Instruments Sl. No. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-Duty (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWL

1[SCHEDULE I (See section 3) Stamp duty on instruments Sl. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-duty No. (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT of a debt Ten Taka exceed, in One thousand Taka in amount or value, written or signed by, or on behalf of, a debtor in order to supply evidence of such debt in any book (other than a banker’s pass book) or on a separate piece of paper where such book or paper is left in the creditors possession: Provided that such acknowledgement does not contain any promise to pay the debt or any stipulation to pay interest or to deliver any goods or other property. 2 ADMINISTRATION BOND, including a bond given under section 6 of the Government Savings Banks Act, 1873, or section 291 or section 375 or section 376 of the Succession Act, 1925- (a) Where the amount does not The same duty as a exceed Taka 5,000; and BOND (No. 15) for such amount (b) In any other case. Two hundred Taka 3 ADOPTION-DEED, that is to say, any Five thousand Taka instrument (other than a WILL), recording an adoption, or conferring or purporting to confer an authority to adopt. ADVOCATE - See ENTRY AS AN ADVOCATE (No. 30) 1 SCHEDULE I was substituted by section 4 of the Finance Act, 2012 (Act No. XXVI of 2012) (with effect from 1st July, 2012). 4 AFFIDAVIT, including an affirmation Two hundred Taka or declaration in the case of persons by law allowed to affirm or declare instead of swearing. EXEMPTIONS Affidavit or declaration in writing when made- (a) As a condition of enlistment under the Army Act, 1952; (b) For the immediate purpose of being field or used in any court or before the officer of any court; or (c) For the sole purpose of enabling any person to receive any pension or charitable allowance. -

Bangladesh Sociological Society

Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology Volume 8, Number 2. July 2011 Note from the Editor 3 Estimation of Population and Food Grain Production Dayal Talukder and 4 In Bangladesh by 2020: A Simple Moving Average Love Chile Approach to a Time Series Analysis Women Empowerment or Autonomy: A Comparative Md. Morshedul Haque, 17 View in Bangladesh Context Towfiqua Mahfuza Islam Md. Ismail Tareque and Md. Golam Mostofa Socio-economic Characteristics and English M. Obaidul Hamid 31 Language Achievement in Rural Bangladesh Parental Socio-Economic Status as Correlate of O.S. Elgbeleye and 51 Child Labour in Ile-Ife, Nigeria M.O. Olasupo Managing Bullying Problems in Nigerian Secondary Oyaziwo Aluede 60 Schools: Some Interventions for Implementation Implications of the Ranking of Community Participation Steve Metiboba and 69 Strategies in Health Development by Selected Rural Olufemi Adewole Communities in O-Kun Yoruba, Kogi State, Nigeria Issues, Problems and Policies in Agricultural Credit: Olatomide W. Olowa and 87 A Review of Agricultural Credit in Nigeria Omowumi A. Olowa Conceptualising Northeast India: A Discursive Thongkholal Haokip 109 Analysis on Diversity ISSN 1819-8465 The Official Journal of Bangladesh Sociological Society Committed to the advancement of sociological research and publication. Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology Volume 8, Number 2. July 2011 2 Bangladesh e-Journal of Sociology (Biannual e-Journal of the Bangladesh Sociological Society) Editor Nazrul Islam Independent University, Bangladesh Associate Editor Managing Editor Book Review Editor S. Aminul Islam M. Imdadul Haque A.I.Mahbub Uddin Ahmed University of Dhaka University of Dhaka University of Dhaka Web Master Faridul Islam, University of Dhaka Emails: [email protected] [email protected] Published on the Internet URL: http://www.bangladeshsociology.org Published by Bangladesh Sociological Society From School of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB) Phone: 88-02-840-1645, Ext. -

Torture in Bangladesh 1971-2004

TORTURE IN BANGLADESH 1971-2004 MAKING INTERNATIONAL COMMITMENTS A REALITY AND PROVIDING JUSTICE AND REPARATIONS TO VICTIMS AUGUST 2004 REALISED WITH FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN INITIATIVE FOR DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN RIGHTS The Redress Trust 87 Vauxhall Walk, 3rd Floor London, SE11 5HJ Tel: +44 (0)207 793 1777 Fax: +44(0)207 793 1719 Website: www.redress.org 1 TORTURE IN BANGLADESH 1971- 2004 INDEX I. INTRODUCTION ................................ ................................ ................................ .............. 4 II. CONTEXT OF TORTURE IN BANGLADESH ................................ ................................ .. 5 A. POLITICAL HISTORY..............................................................................................................................5 B. TORTURE AND OTHER SERIOUS ABUSES COMMITTED IN THE COURSE OF THE 1971 WAR.....7 i. Violations attributed to Pakistani forces and “collaborators”..................................................................................................7 ii. Violations attributed to the Mukthi Bahini and Bengali civilians.............................................................................................8 C. THE PRACTICE OF TORTURE IN BANGLADESH FROM 1971-2004...................................................9 III. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW AND IMPLEMENTATION IN DOMESTIC LAW ................................ ................................ .......... 13 A. INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS .........................................................................................................13 -

International Legal Framework and Animal

Global Journal of Politics and Law Research Vol.6, No.6, pp.16-28, October 2018 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ANIMAL WELFARE: PARTICIPATION OF BANGLADESH Rowshan Jahan Farhana Assistant Professor, Department of Law, Southern University Bangladesh ABSTRACT: Animals are significantly important for our mother earth because the existence of many species depend on the continued survival of others and it is predominant to ensure the conservation and sustainable management of animal resources. This research work tries to kindle on the existing international initiatives covering animal welfare, nevertheless a comprehensive and universal global treaty may not be proved effective in all aspects of international initiatives will be proved useful in case of migratory animals, endangered species and trading of animals whose range extends beyond national boundaries. This research work analyses the current situation and achievements to date of the major international instrument in addressing the threats posed wild animal, marine animals, domestic animals and migratory species. This article also tries to explain the challenges which these instruments face and parallelly addresses the participation of Bangladesh in these international treaties. This research work also outlines the potential scope for further development and seeks to demonstrate that the national animal management system should be flourished in the light of international standard. KEYWORDS: Animal Rights, Animal Welfare, International Instrument, Bangladesh INTRODUCTION Earth is one of the most unique planets of the universe because it is excellently adorned with various species of living beings. Non-human animal is an indispensable component of the natural resource and this resource should not be depleted by over-exploitation. -

9 July 2014 Hon. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Office of the Prime

[email protected] • www.law-democracy.org • tel: +1 902 431-3688 • fax: +1 902 431-3689 39 Chartwell Lane, Halifax, N.S., B3M 3S7, Canada NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations www.lrwc.org; [email protected]; Tel: +1 604 738 0338; Fax: +1 604 736 1175 3220 West 13th Avenue, Vancouver, B.C. CANADA V6K 2V5 9 July 2014 Hon. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Office of the Prime Minister Gona Bhaban, Old Sangsad Bhaban, Tejgaon Dhaka, Bangladesh. Email: [email protected] Dear Prime Minister Hasina, We are writing on behalf of the Centre for Law and Democracy (CLD) and Lawyers Rights Watch Canada (LRWC). CLD is an international human rights NGO that specialises in providing legal and policy expertise to promote foundational rights for democracy, including freedom of association and of expression. LRWC is a committee of Canadian lawyers who promote human rights and the rule of law internationally, and provide support to lawyers and other human rights defenders in danger because of their advocacy. Our organisations have grave concerns about the proposed Foreign Donations (Voluntary Activities) Regulation Act, 2014 (the Bill), which has been approved by Cabinet and is pending review by Parliament. We believe that the Bill opens the door to significant governmental control over NGOs’ ability to operate and raise funds, and that it fails to respect the rights to freedom of association and freedom of expression, both of which are guaranteed in Bangladesh’s constitution, at Articles 38 and 39, respectively, as well as in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Bangladesh ratified on 6 September 2000. -

Jasimuddin - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Jasimuddin - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Jasimuddin(1 January 1903 - 13 March 1976) Jasimuddin (Bengali: ??????????; full name Jasimuddin Mollah) was a Bengali poet, songwriter, prose writer, folklore collector and radio personality. He is commonly known in Bangladesh as Polli Kobi (The Rural Poet), for his faithful rendition of Bengali folklore in his works. Jasimuddin was also one of the pioneers of the progressive and non-communal cultural movement in East Pakistan. <b> Early Life and Career </b> Jasimuddin was born in the village of Tambulkhana in Faridpur District in the house of his maternal uncle. His father, Ansaruddin Mollah, was a school-teacher. Jasimuddin received early education at Faridpur Welfare School. He matriculated from Faridpur Zilla School in 1921. Jasimuddin completed IA from Rajendra College in 1924. He obtained his BA and MA degree in Bengali from the University of Calcutta in 1929 and 1931 respectively. From 1931 to 1937, Jasimuddin worked with Dinesh Chandra Sen as a collector of folk literature. Jasimuddin is one of the compilers of Purbo-Bongo Gitika (Ballads of East Bengal). He collected more than 10,000 folk songs, some of which has been included in his song compilations Jari Gaan and Murshida Gaan. He also wrote voluminously on the interpretation and philosophy of Bengali folklore. Jasimuddin joined the University of Dhaka in 1938 as a Lecturer. He left the university in 1944 and joined the Department of Information and Broadcasting. He worked there until his retirement as Deputy Director in 1962. Jasimuddin died on 13 March 1976 and was buried near his ancestral home at Gobindapur, Faridpur. -

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's Commitment Gender Equality And

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Commitment Gender Equality and Women Empowerment The Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibar Rahman started the process of uplifting the women status by establishing equal rights of woman with man in all spheres of the state and of public life as constitutional obligation under Article-28. The Government of Hon’ble Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has undertaken various steps to ensure women and children development in Bangladesh. Through her Vision 2021 and 2041 a momentum has been created for taking forward Bangladesh to a middle and high income level respectively. The 7th Five Year Plan (2016-2020) of the Bangladesh government, considers women’s engagement in political and economic activities as a cross-cutting issue and one of the main drivers of transformation. Honorable Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina received 'Champions of the Earth’ Award in 2015 Present government is committed to attaining the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of gender equality and empowering women as well as implementing the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Beijing Platform for Action. Bangladesh has already substantially achieved the MDG3 as it has achieved gender parity in primary and secondary education at the national level, among other successes of the MDGs. Bangladesh has been working relentlessly to ensure women’s overall development by ensuring their equal and active participation in the mainstream socio-economic activities and removing the various impediments to their empowerment. Ministry of Women and Children Affairs Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh May 2016 Important Initiatives of Women Empowerment in Bangladesh 1. -

Rule of Law in Bangladesh Constitution

Rule Of Law In Bangladesh Constitution Is Vilhelm single-tax or unfaulty after Spartan Clark smites so studiedly? Stratiform Aldo foregrounds interjectionally or revalorize stoically when Francisco is shrunk. Franklin dandifies his minivet prenegotiated initially, but sagittiform Avraham never augur so westwards. Transitional justice concerns procedural differences between the public authorities hold elections and bangladesh law rule of constitution in court of the removal or pandemic continues to enjoy for the president earlier Under these law rule of bangladesh constitution in addition to meet development potential internal resources division shall have? Authorities have meanwhile started to arrest opponents and perceived allies of the rebellion. If late people have children or have any grandson or generations down wards than mother will get one sixth of property. Others have considered the need for good and principled leadership in a democratic constitutional order, it is high time to establish a socialist society where fundamental rights of the people, when he said that the king must be under God and Law and thus vindicated the supremacy of Law over the pretensions of the executives. Constitution of Bangladesh wields enormous potentials for the judiciary to develop jurisprudence for strengthening rule of law in the country. But what Dicey probably criticized was exercise of discretionary powers not supported by law. In bangladesh law in constitution of rule of the gruesome murders of, as the status. The theoretical appearance of this prerogative is too grave to consider it lightly especially in Bangladesh where the President comes through a political nomination and a mere election by the members of the Parliament. -

Economic Relations Division (ERD) Ministry of Finance

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Economic Relations Division (ERD) Ministry of Finance Knowledge for Development Management (K4DM) for ERD UN Wing Knowledge for Development Management Project (K4DM) FINAL EVALUATION REPORT October 2019 The study is carried out with technical and financial support from UNDP Bangladesh UNDP Bangladesh 1 Project / Outcome Information Project/outcome title Knowledge for Development Management (K4DM) for ERD UN Wing Atlas ID 00091143 CPD OUTCOME 2: Develop and implement improved social policies and programmes that focus on good governance, reduction of structural inequalities and advancement of vulnerable individuals and groups. Corporate outcome and output CPD OUTPUT 2.1: Civil society, interest groups, relevant government agencies and political parties haves tools and knowledge to set agendas and to develop platforms for building consensus on national issues. Country Bangladesh Region Asia and the Pacific Date project document 27 March 2014 signed Start Planned end Project dates September 2014 June 2020 BDT 24,0000000 (UNDP 23,40,00000 and GoB 60,00000) Project budget USD 03 million 736,705 USD (UNDP) Project expenditure at the time of evaluation 33.8 Lakhs BDT (GoB) Funding source UNDP and the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) Implementing party UN Wing of Economic Relations Division, Ministry of Finance, GoB Evaluation Information Evaluation type (project/ Outcome outcome/thematic/country Programme, etc.) Final/midterm review/ Final other Start End Period under evaluation September 2014 December 2019 Evaluators Prof. Dr. Ferdous Arfina Osman and Dr. Nizamuddin Al-Hussainy Evaluator email address [email protected] ; [email protected] Start Completion Evaluation dates 09 June 2019 October 2019 2 EVALUATION TEAM Dr.