The Itinerary of the Tragic Hero Through Shane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

34 Writers Head to 7Th Annual Johnny Mercer Foundation Writers Colony at Goodspeed Musicals

NEWS RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: Elisa Hale at (860) 873-8664, ext. 323 [email protected] Dan McMahon at (860) 873-8664, ext. 324 [email protected] 34 Writers Head to 7th Annual Johnny Mercer Foundation Writers Colony at Goodspeed Musicals – 21 Brand New Musicals will be part of this exclusive month-long retreat – This year’s participants boast credits as diverse as: Songwriters of India Aire’s “High Above” (T. Rosser, C. Sohne) Music Director for NY branch of Playing For Change (O. Matias) Composer for PBS (M. Medeiros) Author of Muppets Meet the Classic series (E. F. Jackson) Founder of RANGE a capella (R. Baum) Lyricist for Cirque du Soleil’s Paramour (J. Stafford) Member of the Board of Directors for The Lilly Awards Foundation and Founding Director of MAESTRA (G. Stitt) Celebrated Recording Artists MIGHTY KATE (K. Pfaffl) Teaching artist working with NYC Public Charter schools and the Rose M. Singer Center on Riker’s Island (I. Fields Stewart) Broadway Music Director/Arranger for If/Then, American Idiot, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee and others (C. Dean) EAST HADDAM, CONN.,JANUARY 8 , 2019: In what has become an annual ritual, a total of 34 established and emerging composers, lyricists, and librettists will converge on the Goodspeed campus from mid-January through mid-February 2019 to participate in the Johnny Mercer Foundation Writers Colony at Goodspeed Musicals. The writing teams, representing 21 new musicals, will populate the campus, creating a truly exciting environment for discovery and inspiration. The Johnny Mercer Writers Colony at Goodspeed is an unparalleled, long-term residency program devoted exclusively to musical theatre writing. -

Western Movie Trivia Questions

WESTERN MOVIE TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Who plays the sheriff in Unforgiven (1992)? 2> Who is the director and producer of Appaloosa (2008)? 3> Which Native American tribe attacked the village, defended by Dunbar (Dances with Wolves)? 4> Who is Shane from a 1953 movie of the same name? 5> Who really shot Liberty Valance (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance)? 6> Which tribe adopted Jack Crab, played by Dustin Hoffman (Little Big Man)? 7> Jeff Bridges portrayed famous character of the Dude in Big Lebowski. Which of the following westerns also featured a character named Dude? 8> The Magnificent Seven is a western remake of which famous movie? 9> Owen Thursday is a graduate of which military school (Fort Apache)? 10> What does the name Manco mean (For a Few Dollars More)? 11> Who plays Seth Bullock in TV series Deadwood? 12> John Wayne won an Oscar for his role in which movie? 13> What is Ringo's first name (The Gunfighter)? 14> The action takes place in Rio Arriba in... 15> What is the US title for a Sergio Leone film Duck, You Sucker! ? Answers: 1> Gene Hackman - A memorable quote is 'It's a hell of a thing killin' a man. You take away all he's got and all he's ever gonna have.' 2> Ed Harris - Alan Miller directed a film called The Appaloosa in 1966, starring Marlon Brando. 3> Pawnee - Some of the Pawnee people practiced child sacrifice. 4> A gunslinger - The last living member of the cast, Jack Palance, died in 2006. -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

October 4, 2016 (XXXIII:6) Joseph L. Mankiewicz: ALL ABOUT EVE (1950), 138 Min

October 4, 2016 (XXXIII:6) Joseph L. Mankiewicz: ALL ABOUT EVE (1950), 138 min All About Eve received 14 Academy Award nominations and won 6 of them: picture, director, supporting actor, sound, screenplay, costume design. It probably would have won two more if four members of the cast hasn’t been in direct competition with one another: Davis and Baxter for Best Actress and Celeste Holm and Thelma Ritter for Best Supporting Actress. The story is that the studio tried to get Baxter to go for Supporting but she refused because she already had one of those and wanted to move up. Years later, the same story goes, she allowed as maybe she made a bad career move there and Bette David allowed as she was finally right about something. Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz Written by Joseph L. Mankiewicz (screenplay) Mary Orr (story "The Wisdom of Eve", uncredited) Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck Music Alfred Newman Cinematography Milton R. Krasner Film Editing Barbara McLean Art Direction George W. Davis and Lyle R. Wheeler Eddie Fisher…Stage Manager Set Decoration Thomas Little and Walter M. Scott William Pullen…Clerk Claude Stroud…Pianist Cast Eugene Borden…Frenchman Bette Davis…Margo Channing Helen Mowery…Reporter Anne Baxter…Eve Harrington Steven Geray…Captain of Waiters George Sanders…Addison DeWitt Celeste Holm…Karen Richards Joseph L. Mankiewicz (b. February 11, 1909 in Wilkes- Gary Merrill…Bill Simpson Barre, Pennsylvania—d. February 5, 1993, age 83, in Hugh Marlowe…Lloyd Richards Bedford, New York) started in the film industry Gregory Ratoff…Max Fabian translating intertitle cards for Paramount in Berlin. -

July 1978 Scv^ Monthly for the Press && the Museum of Modern Art Frl 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y

d^c July 1978 ScV^ Monthly for the Press && The Museum of Modern Art frl 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Department of Public Information, (212)956-2648 What' s New Page 1 What's Coming Up Page 2 Current Exhibitions Page 3-4 Gallery Talks, Special Events Page 4-5 Ongoing Page Museum Hours, Admission Fees Page 6 Events for Children , Page 6 WHAT'S NEW DRAWINGS Artists and Writers Jul 10—Sep 24 An exhibition of 75 drawings from the Museum Collection ranging in date from 1889 to 1976. These drawings are portraits of 20th- century American and European painters and sculptors, poets and philosophers, novelists and critics. Portraits of writers in clude those of John Ashbery, Joe Bousquet, Bertolt Brecht, John Dewey, Iwan Goll, Max Jacob, James Joyce, Frank O'Hara, Kenneth Koch, Katherine Anne Porter, Albert Schweitzer, Gertrude Stein, Tristan Tzara, and Glenway Wescott. Among the artists represent ed by self-portraits are Botero, Chagall, Duchamp, Hartley, Kirchner, Laurencin, Matisse, Orozco, Samaras, Shahn, Sheeler, and Spilliaert. Directed by William S. Lieberman, Director, De partment of Drawings. (Sachs Galleries, 3rd floor) VARIETY OF MEDIA Selections from the Art Lending Service Jul 10—Sep 5 An exhibition/sale of works in a variety of media. (Penthouse, 6th floor) PHOTOGRAPHY Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960 Jul 28—Oct 2 This exhibition of approximately 200 prints attempts to provide a critical overview of the new American photography of the past Press Preview two decades. The central thesis of the exhibition claims that Jul 26 the basic dichotomy in contemporary photography distinguishes llam-4pm those who think of photography fundamentally as a means of self- expnession from those who think of it as a method of exploration. -

1 This Course Focuses on Representations of Jesus of Nazareth in 20Th-Century Film, Paying Particular Attention to the Ways That

Fall 2015 Hybrid, T/F 12:35–1:55, RAB 104 Professor Wasserman Tues meetings Face to Face Department of Religion Fri meetings Online 110 Loree Building, Douglas Campus New Brunswick, NJ Office hours: [email protected] Tues 11–12 (Loree 110, Douglas) Phone: (401) 742–2540 Tues 2:30–3:30 (B & N, College Ave) Skype/Adobe Connect, by appt. RELIGION 120: JESUS AT THE MOVIES This course focuses on representations of Jesus of Nazareth in 20th-century film, paying particular attention to the ways that writers, directors, and production-teams creatively retell Jesus stories to meet changing interests and pre-occupations. We will begin by investigating films as forms of entertainment, technological products, and object of artistic, social, and historical analysis. We will then treat early textual representations of Jesus’s life drawn from the canonical and non-canonical gospels before returning to the media of film. We will explore the early silent films such as the King of Kings (DeMille, 1927), later big budget epics such as The Greatest Story Ever Told (Stevens, 1965), The Last Temptation of Christ (Scorsese, 1988), and the Passion of Christ (Gibson, 2004). We will also consider musicals such as Jesus Christ Superstar and the less mainstream, art-house films by Pier Pasolini and Denys Arcand. 1. One in-class midterm scheduled for Oct. 20, to be geared towards paper-writing. Students will prepare responses to essay questions circulated in advance and then write them during the 80 minute class period. 20%. 2. Two short papers (1500–2000 words), to be revised in response to comments from the instructor and from peer reviewers. -

ACADEMY MUSEUM of MOTION PICTURES Collection Highlights

ACADEMY MUSEUM OF MOTION PICTURES Collection Highlights OVERVIEW The Academy Museum will draw from the unparalleled collection of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, which contains a vast range of motion picture production and history-related objects and technology, works on paper, still and moving images covering the history of motion picture in the United States and throughout the world. The collections include more than 12 million photographs, 190,000 film and video assets, 80,000 screenplays, 61,000 posters, and 104,000 pieces of production art. The collection also includes more than 1,600 special collections of film legends such as Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Alfred Hitchcock, and John Huston. These special collections contain production files, personal correspondence, clippings, contracts, manuscripts, scrapbooks, storyboards, and more. The Academy’s collecting divisions work collaboratively to acquire, preserve, digitize, and exhibit the broad range of materials entrusted to their care by generations of filmmakers and collectors. The Academy Museum has actively been acquiring three-dimensional motion picture objects since 2008. Its holdings now number approximately 2,500 items representing motion picture technology, costume design, production design, makeup and hairstyling, promotional materials and memorabilia, and awards. MOTION PICTURE TECHNOLOGY The collection includes examples of pre-cinema devices, early and modern motion picture cameras and projectors, sound, editing and lighting equipment, and other landmark -

Programming Ideas

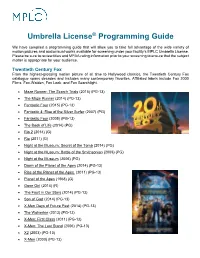

Umbrella License® Programming Guide We have compiled a programming guide that will allow you to take full advantage of the wide variety of motion pictures and audiovisual works available for screening under your facility’s MPLC Umbrella License. Please be sure to review titles and MPAA rating information prior to your screening to ensure that the subject matter is appropriate for your audience. Twentieth Century Fox From the highest-grossing motion picture of all time to Hollywood classics, the Twentieth Century Fox catalogue spans decades and includes many contemporary favorites. Affiliated labels include Fox 2000 Films, Fox-Walden, Fox Look, and Fox Searchlight. • Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015) (PG-13) • The Maze Runner (2014) (PG-13) • Fantastic Four (2015) (PG-13) • Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) (PG) • Fantastic Four (2005) (PG-13) • The Book of Life (2014) (PG) • Rio 2 (2014) (G) • Rio (2011) (G) • Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014) (PG) • Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) (PG) • Night at the Museum (2006) (PG) • Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) (PG-13) • Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) (PG-13) • Planet of the Apes (1968) (G) • Gone Girl (2014) (R) • The Fault in Our Stars (2014) (PG-13) • Son of God (2014) (PG-13) • X-Men Days of Future Past (2014) (PG-13) • The Wolverine (2013) (PG-13) • X-Men: First Class (2011) (PG-13) • X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) (PG-13) • X2 (2003) (PG-13) • X-Men (2000) (PG-13) • 12 Years a Slave (2013) (R) • A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Robert Duvall

VOICE Journal of the Alex Film Society Vol. 14, No. 1 February 2, 2008, 2 pm & 8 pm 02/08 of theTHEATRE Gregory Peck By Randy Carter has to age six decades over the course of the film regory Peck has and Zanuck thought Peck always been a could carry it off. Although Gleading man. He the film did well at the never played a waiter box office it didn’t recoup with two lines or a police Zanuck’s $3 million dollar officer who gets killed in investment. But Peck got an the first reel. A California Oscar® nomination for Best boy from La Jolla, he Actor and his position as a went to San Diego State top leading man was minted and Cal, did some college in only his second film. He theatre and headed to New would be nominated three York. A student of Sanford more times in the next four Meisner, he played the years for The Yearling (1946), lead in his first Broadway Gentleman’s Agreement production, “The Morning (1947) and Twelve O’ Clock Star”, a New York version High (1950). of a London hit by the Welsh actor/playwright Emlyn Williams. This was 1942 Gentleman’s Agreement teamed Peck with New Yorker and a few good notices, a round of Hollywood meetings Elia Kazan in a film about Anti-Semitism. Peck actually set up by his agent Leland Hayward, set the stage for played a gentile impersonating a Jew to observe the his first film role in the RKO production of Days of depth of prejudice in America. -

Pioneer Film Director Honored / HENRY KING

The Museum of Modern Art 'iWest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modemart NO. 57 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PIONEER FILM DIRECTOR HONORED SEVEN WEEK RETROSPECTIVE FOR HENRY KING CO-SPONSORED BY MUSEUM AND DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA "...the most underpublicized filmmaker in Hollywood. This tall, lean, handsome, urbane, but unflamboyant model of a corporation president makes film hits so easily, so efficiently, and so calmly that he is not news in a community of blaring trumpets, crashing cymbals and screaming egos." -Frank Capra Henry King, one of the founding fathers of American film, who began his career early in the century, remains today one of the legendary figures in Hollywood, and though he preserves his privacy, his films such as "The Song of Bernadette," "Twelve O'clock High" and "The Gunfighter" speak for themselves, and these and other major works will be part of a seven week retrospective given in King's honor by New York's Museum of Modern Art in association with the Directors Guild of America. The Virginia-born director, who has specialized, like D.W. Griffith and John Ford, in Americana themes since his first classic, "Tol'able David," and later with "State Fair", "In Old Chicago," "Jesse James" and "Alexander's Ragtime Band," will make a trip from the West Coast to New York to participate in the opening of this program. On June 29 and 30, he will address the Museum audiences, although he seldom makes public appearances. While he contributed to Hollywood's worldwide reputation, King, who recognized such early superstars as Richard Barthelmess, Ronald Colman and Gary Cooper and gave them their first leading roles on the screen, has managed to retain his relative anonymity in an ostentatious environment. -

A Guild Is Born Dorothy Arzner

80-YEAR ANNIVERSARY The Screen KING VIDOR 1938 >“Women’s dramatic sense is “Directors Guild DOROTHY invaluable to the motion picture was organized industry,” said Dorothy Arzner, solely by ARZNER whose contributions include and for the First Female 80 YEARS STRONG motion picture being the first female member Member 1933 >The formation of the Directors director…. We of the Directors Guild. In early A GUILD Guild had been percolating for a are not anti- Hollywood, Arzner was a typist, number of years. Amid nationwide anything: the screenwriter, editor, and ultimately, director. IS BORN labor unrest in the country, the Guild being She is believed to have developed the boom mic, studios had been squeezing directors formed for the enabling actors to move and speak more easily purpose of both financially and creatively. The first step toward in early talkies. At one time under contract to assisting and Paramount, Arzner is organizing a guild occurred in 1933 outside the Hol- improving the lywood Roosevelt Hotel, after a meeting in which best known for directing director’s work such strong personalities the studios announced a 50 percent across-the-board in the form of pay cut. After the meeting, King Vidor and a handful a collective as Clara Bow, Claudette of directors congregated on the sidewalk and knew body, rather Colbert, Katharine something had to be done. They understood, as Vidor than as an Hepburn, and Joan put it, “We must have a guild to speak [for us], and individual. Crawford in films such not the individual, who can be hurt by standing up as Honor Among Lovers “I worked on my for his rights.” That guild was born in late 1935 and ” (1931) and Christopher first project under Strong (1933).