Unit 25 Eighteenth Century in Indian History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agromet Advisory Bulletin for the State of Haryana Bulletin No

Agromet Advisory Bulletin for the State of Haryana Bulletin No. 77/2021 Issued on 24.09.2021 Part A: Realized and forecast weather Summary of past weather over the State during (21.09.2021 to 23.09.2021) Light to Moderate Rainfall occured at many places with Moderate to Heavy rainfall occurred at isolated places on 21th and at most places on 22th & 23th in the state. Mean Maximum Temperatures varied between 30-32oC in Eastern Haryana which were 01-02oC below normal and in Western Haryana between 33-35 oC which were 01-02 oC below normal. Mean Minimum Temperatures varied between 24-26 oC Eastern Haryana which were 02-03oC above normal and in Western Haryana between 24-26 oC which were 00-01 oC above normal. Chief amounts of rainfall (in cms):- 21.09.2021- Gohana (dist Sonepat) 9, Khanpur Rev (dist Sonepat) 7, Panipat (dist Panipat) 7, Kalka (dist Panchkula) 5, Dadri (dist Charkhi Dadri) 5, Panchkula (dist Panchkula) 5, Ganaur (dist Sonepat) 4, Israna (dist Panipat) 4, Fatehabad (dist Fatehabad) 4, Madluda Rev (dist Panipat) 4, Panchkula Aws (dist Panchkula) 3, Sonepat (dist Sonepat) 3, Naraingarh (dist Ambala) 3, Beri (dist Jhajjar) 2, Sirsa Aws (dist Sirsa) 2, Kharkoda (dist Sonepat) 2, Jhahhar (dist Jhajjar) 2, Uklana Rly (dist Hisar) 2, Uklana Rev (dist Hisar) 2, Raipur Rani (dist Panchkula) 2, Jhirka (dist Nuh) 2, Hodal (dist Palwal) 2, Rai Rev (dist Sonepat) 2, Morni (dist Panchkula) 2, Sirsa (dist Sirsa) 1, Hassanpur (dist Palwal) 1, Partapnagar Rev (dist Yamuna Nagar) 1, Bahadurgarh (dist Jhajjar) 1, Jagdishpur Aws (dist Sonepat) -

Legal Control on Groundwater Resources

LEGAL CONTROL ON GROUNDWATER RESOURCES ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^Ijiloslopljp A IN BY HARIS UMAR Under the Supervision of PROF. (DR.) IQBAL ALI KHAN (Dean & Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LAW ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ABSTRACT Preservation of water has been the essence of Vedic culture. However, there was a change in the attitude and belief of our people through modernization. Rapid industrialization and urbanization infused material culture and in this process of development, the natural resources like ground water had lost its importance. Industrial and agriculture boom has resulted in ground water depletion and pollution. Its easy access has always attracted human activities, but its complexity in understanding has led to misuse and abuse. According to State Ground Water Board officials, water tables are dropping by six meter or more each year. It was learnt that farmers in the country, a generation ago used bullocks to lift water from shallow wells in leather buckets. But now they are drawing water from SOOmetres below ground using electric pumps. The pumps powered by heavy subsidy are working day and night to irrigate fields of more water consuming crops like rice, banana and sugarcane. The law allows landowners practically unrestricted right of extraction of groundwater from under their plots. This vital question needs to be addressed properly so as to develop a correct and cognizable perception about legal framework of rights in the domain of water regulation. The problem of water pollution is as old as the evolution of human being on this planet. -

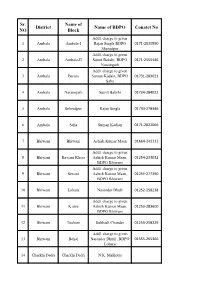

Sr. NO District Name of Block Name of BDPO Conatct No

Sr. Name of District Name of BDPO Conatct No NO Block Addl. charge to given 1 Ambala Ambala-I Rajan Singla BDPO 0171-2530550 Shazadpur Addl. charge to given 2 Ambala Ambala-II Sumit Bakshi, BDPO 0171-2555446 Naraingarh Addl. charge to given 3 Ambala Barara Suman Kadain, BDPO 01731-283021 Saha 4 Ambala Naraingarh Sumit Bakshi 01734-284022 5 Ambala Sehzadpur Rajan Singla 01734-278346 6 Ambala Saha Suman Kadian 0171-2822066 7 Bhiwani Bhiwani Ashish Kumar Maan 01664-242212 Addl. charge to given 8 Bhiwani Bawani Khera Ashish Kumar Maan, 01254-233032 BDPO Bhiwani Addl. charge to given 9 Bhiwani Siwani Ashish Kumar Maan, 01255-277390 BDPO Bhiwani 10 Bhiwani Loharu Narender Dhull 01252-258238 Addl. charge to given 11 Bhiwani K airu Ashish Kumar Maan, 01253-283600 BDPO Bhiwani 12 Bhiwani Tosham Subhash Chander 01253-258229 Addl. charge to given 13 Bhiwani Behal Narender Dhull , BDPO 01555-265366 Loharu 14 Charkhi Dadri Charkhi Dadri N.K. Malhotra Addl. charge to given 15 Charkhi Dadri Bond Narender Singh, BDPO 01252-220071 Charkhi Dadri Addl. charge to given 16 Charkhi Dadri Jhoju Ashok Kumar Chikara, 01250-220053 BDPO Badhra 17 Charkhi Dadri Badhra Jitender Kumar 01252-253295 18 Faridabad Faridabad Pardeep -I (ESM) 0129-4077237 19 Faridabad Ballabgarh Pooja Sharma 0129-2242244 Addl. charge to given 20 Faridabad Tigaon Pardeep-I, BDPO 9991188187/land line not av Faridabad Addl. charge to given 21 Faridabad Prithla Pooja Sharma, BDPO 01275-262386 Ballabgarh 22 Fatehabad Fatehabad Sombir 01667-220018 Addl. charge to given 23 Fatehabad Ratia Ravinder Kumar, BDPO 01697-250052 Bhuna 24 Fatehabad Tohana Narender Singh 01692-230064 Addl. -

Unpaid Dividend-16-17-I2 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 737532.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE PLOT NO 10 AIYSSA GARDEN IN301637-41195970- Amount for unclaimed and A BALAN NA LAKSHMINAGAR MAELAMAIYUR INDIA Tamil Nadu 603002 400.00 24-Feb-2024 0000 unpaid dividend -

1500114602.Pdf

List of candidates for the post of for the post of Chowkidar (Class-IV) on daily wages for evaluation /verification of documents Sr. No Name & Particulars of Candidate applied for the post of Chowkidar Date of Birth Category Date of (Class-IV) Verification of documents 1 Sh. Brij Lal s/o sh Jeet Ram r/o Vill. Banan PO Piplughat Tehsil Arki Distt. Solan 18/11/1975 General 04/09/2017 HP 173235 2 Sh. abdul azim,sk.akshed ,village poshla,p.o-nurpur p.s-nanvr,distt-birbhum,state- 20/12/1991 General 04/09/2017 west bengal 3 Sh. Ajay Singh s.o krishan Singh Vill Bhatoli PO Diana Tehsil fatehpur District 14/01/1988 General 04/09/2017 Kangra HP 4 Sh. Akshay Kumar D/o Dilbag Singh VPO Marwari Tehsil Ghanari Distt Una HP 09/02/1997 General 04/09/2017 174319 5 Sh. Akshay Sharma S/O Sh Deepak Sharma VPO pathiar tehsil Nagrota Bagwan 21/06/1990 General 04/09/2017 Distt Kangra 176047 HP 6 Amar Singh S/o Dhani Ram Vill PO chalharg Tehsil J/Nagar Distt Mandi HP 02/10/1974 General 04/09/2017 7 Amar Singh S/o Jai singh Vill bagain Po Malon The Sunder Nagar Distt Mandi Hp 13/05/1987 General 04/09/2017 8 Amit Jamwal S/o Ajit Jamwal Vill Upper Sohar Po Sandhole Tehsil Sarkaghat 29/01/1981 General 04/09/2017 Distt Mandi HP 176090 9 Ankesh Kumar S/o Subhash chand VPO Baag Tehsil Laj Bhoraj Distt Mandi 30/09/1997 General 04/09/2017 HP175032 10 Anu bala W/o Pankaj ThakurVPO Chhiyal Teh manali Distt Kullu HP 18/08/1988 General 04/09/2017 11 Arshad Hussain S/O Sh. -

Till:Fr Ici-) 4R-Zs-T Tilicil

Till:Fr ici-) 4r-zs-T tilicil, aiTtTift ,-Id(-1 01\3 -1 t5 31 .7r 3irt41At, .1 c,1- 0 0 C.No. V111/6/ICD/PPG/RTI/105/2014/Pt-1 I Dated: liibl 202) Public Notice No ES i 2021 In accordance with the provisions of Section 5(1) & Section 19(1) of the Right to Information Act, 2005 and modification to Public Notice No 44/2020 issued under C. No. V111/6/1CD/PPG/RTI/05/2014/Pt- 1 and consequent upon transfer of officers, the following officers are hereby designated as "Appellate Authority" and "Central Public Information Officers (CPIO)" for the purpose of the said Act, for the jurisdiction of ICD Patparganj and Other ICDs Commissionerate until further orders. S.N Office Details of CPIO Details of Appellate Authority o. Location Name of the officer & Address & Contact Contact Name of the Address & Designation Details No. officer & Contact Details Designation 1 ICD PPG ICD-Patparganj & 0I 1- (HQ) Other ICDs, Near 21211105 Gazipur, Delhi- 110096 2 ICD — PPG ICD-Patparganj & 011- Other ICDs, Near 21211115 Gazipur, Delhi- 110096 3 ICD- Anuj Aggarwal, Deputy Village Jhattipur, 0180- Jhattipur Commissioner of Customs Tehsil Samalkha, 2615355 Sanjay Kumar Roy, Distt. Panipat, Additional Commissioner of Haryana Customs , 4 ICD- Barhi V.P.O. Barhi, Tehsil 0180- ICD-Patparganj & Other ICDs Gannur, Distt. 2576203 Delhi-110096 Sonepat, Haryana Tel: 011-21211120 5 ICD-Garhi Prashant Kumar Jaiswal, Opp. Railway 0124- Harsaru Deputy Commissioner Station, Near 2276321 Wazirpur More, Via Pataudi Road,Gurgaon- 122505 6 ICD- Patli Jaya Kumari, Deputy Main Gurgaon 0124- Commissioner Pataudi Road, Opp. -

List of Dedicated Covid Health Centers in Haryana

List of Dedicated Covid Health Centers in Haryana Total Isolation O2 No of SR. District Total ICU Facilty Name Category Type Facilty ID beds Supported Ventilator No Name beds (excluding beds s ICU beds) Military Hospital, Ambala Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 1 AMBALA Govt Hospitals 10699 100 25 9 9 Cantt Health Center / DCHC Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 2 AMBALA Healing Touch Hospital Pvt Private Hospitals 10397 30 20 14 14 Health Center / DCHC Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 3 AMBALA Civil Hospital, Naraingarh Govt Hospitals 10545 12 6 0 0 Health Center / DCHC Railway Hospital, Ambala Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 4 AMBALA Govt Hospitals 10698 6 2 0 0 Cantt Health Center / DCHC Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 5 AMBALA Civil Hospital Ambala Cantt Govt Hospitals 10058 25 10 0 0 Health Center / DCHC Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 6 AMBALA Civil Hospital Ambala City Govt Hospitals 10057 50 20 0 0 Health Center / DCHC Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 7 BHIWANI Krishan Lal Jalan Hospital Govt Hospitals 12726 40 2 0 0 Health Center / DCHC List of Dedicated Covid Health Centers in Haryana Total Isolation O2 No of SR. District Total ICU Facilty Name Category Type Facilty ID beds Supported Ventilator No Name beds (excluding beds s ICU beds) Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 8 BHIWANI Jangra Multispecilaity Hospital Private Hospitals 12717 10 7 1 1 Health Center / DCHC Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 9 BHIWANI Spes Hospital Private Hospitals 10513 12 12 2 2 Health Center / DCHC Cat. II - Dedicated COVID 10 BHIWANI Ch. Bansilal Govt Hospital Govt Hospitals 10043 76 76 5 5 Health Center / DCHC Cat. -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

Delhi Ncr Industrial June 2019 Marketbeats

DELHI NCR INDUSTRIAL JUNE 2019 MARKETBEATS 3-5% 7-8% 2.8 msf GROWTH IN WAREHOUSING GROWTH IN INDUSTRIAL W A R E H OU S E R E N T S ( Y - O - Y) R E N T S ( Y - O - Y ) TRANSACTIONS (H1 2019) ECONOMIC INDICATORS 2017 2018 2019 Forecast HIGHLIGHTS GDP Growth 7.2% 6.8% 7.0% CPI Growth 3.6% 3.5% 3.4% Growth momentum in warehouse leasing Consumer Spending 7.4% 8.1% 7.1% remains unabated Government Final 14.2% 9.2% Consumption Expenditure 15.0% E-commerce and logistics players continued to lead the growth of warehousing sector Source: Oxford Economics, Central Statistics Office in the city, while retailers and consumer durable manufacturers were among other INDUSTRIAL AND WAREHOUSE RENTS H1 2019, HARYANA demand drivers. Amazon, Firstcry, Delhivery, DB Schenker, Rhenus Logistics, Yusen 25 25% Logistics, Voltas leased large warehousing spaces (above 100,000 sf) in H1 2019. The 20 20% first half of 2019 noted a robust 2.8 msf of warehouse transactions, equivalent to the 15 15% 10 10% leasing in entire 2018 demonstrating the persistent growth in warehousing. Tauru 5 5% 0 0% Road, Farrukhnagar, Pataudi Road and Dharuhera in Haryana were the most active for Bilaspur Dharuhera Hassangarh Kundli Faridabad Palwal warehouse leasing transactions. Industrial Rent (INR/sf/month) Warehousing Rent (INR/sf/month) Industrial Rent YoY Growth (%) Warehousing Rent YoY Growth (%) Warehousing and Industrial rents increase H1 2019, UTTAR PRADESH 50 20% Warehousing rents in the Tauru, Bilaspur Kalan, Pataudi corridor increased by 5.3% 40 15% 30 y-o-y backed by healthy demand. -

Administrative Map

Bajghera(61) Badhosra ´ 0.4 0.2 0 0.4 km Raghu Pur Administrative Map Nanak Heri Gram Panchayat : Babupur Block : Gurgaon District : Gurgaon State : Haryana Babupur(60) Choma(62) Dharampur(59) Legend GP Boundary Village Boundary World Street Map Data Source : SOI,NIC,Esri Pawala Khasrupur(57) Mohmadheri(58) Map composed by : RS & GIS Div, NIC Daultabad(53) Sources: Esri, HERE, DeLorme, USGS, Intermap, increment P Corp., NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, MapmyIndia, © OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Community Gurgaon (Rural) (CT) Central West 4 2 0 4 km Ne´w Delhi South West No. Of Households Bahadurgarh Block : Gurgaon Babupur Jhajjar District : Gurgaon South State : Haryana Gurgaon Legend Block Boundary Farrukhnagar GP Boundary Village Boundary Urban_area Village Boundary(No. Of Households) Data Not Available Faridabad 1 - 500 501 - 1000 1001 - 5074 Sohna Ballabgarh Pataudi Data Source : SOI,NIC,Esri Taoru Map composed by : RS & GIS Div, NIC Palwal Rewari Nuh Central West 4 2 0 4 km Ne´w Delhi South West Total Persons Bahadurgarh Block : Gurgaon Babupur Jhajjar District : Gurgaon South State : Haryana Gurgaon Legend Block Boundary Farrukhnagar GP Boundary Village Boundary Urban_area Village Boundary(Total Persons) Data Not Available Faridabad 1 - 1500 1501 - 3000 3001 - 23448 Sohna Ballabgarh Pataudi Data Source : SOI,NIC,Esri Taoru Map composed by : RS & GIS Div, NIC Palwal Rewari Nuh Central West 4 2 0 4 km Ne´w Delhi South West Total Population Male Bahadurgarh Block : Gurgaon Babupur -

February - March 2019 2 84

1 86 February - March 2019 2 84 3 ×¾ÖªÖ¯Ößšü úÖî¿Ö»µÖ ×¾ÖúÖÃÖ ¸üÖê•ÖÖÖ¸ü ¾Ö ˆªÖê•ÖúŸÖÖ ´ÖÖ×ÆüŸÖß ¾Ö ´ÖÖÖÔ¤ü¿ÖÔÖ ëú¦ ×¾ÖªÖ£Öá ´ÖÖÖÔ¤ü¿ÖÔÖ ¯ÖסÖúÖ ´ÖÖÆêü : ±êú²ÖÎã¾ÖÖ¸üß - ´ÖÖ“ÖÔ 2019 †Óú 86 ¾ÖÖ CONTENTS PAGE S. N. PARTICULARS NO. 01 UPSC 2019 – 106 CGS & GEOLOGIST POSTS 1 02 UPSC RECRUITMENT 2019 IES/ ISS EXAM 1 03 RRC RECRUITMENT 2019 2 04 RCFL RECRUITMENT 2019 4 05 CPCRI RECRUITMENT 2019 4 06 ONGC RECRUITMENT 2019 5 07 GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA RECRUITMENT 2019 5 08 CISF RECRUITMENT 2019 NOTIFICATION 6 09 NFL RECRUITMENT 2019 6 10 NATIONAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY RECRUITMENT 2019 6 11 DMRC RECRUITMENT 2019 7 12 CURRENT AFFAIRS OF FEBRUARY 2019 8 13 CURRENT AFFAIRS OF MARCH 2019 15 14 CURRENT AFFAIRS QUESTIONS 18 1 UPSC 2019 – 106 CGS & GEOLOGIST POSTS Name of the Post: UPSC CGS & Geologist Online Form 2019 Post Date: 20-03-2019 Total Vacancy: 106 Brief Information: Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) has given a notification for the recruitment of Combined Geo-Scientist and Geologist Examination 2019. Those Candidates who are interested in the vacancy details & completed all eligibility criteria can read the Notification & Apply Online. Application Fee • Candidates should pay Rs. 200/- • Pay the fee by remitting the money in any Branch of Visa/ Master/ RuPay Credit/ Debit Card or by using Internet Banking of SBI. • Female/ SC/ST/ Persons with Benchmark Disability Candidates are exempted from payment. Important Dates • Starting Date to Apply Online: 20-03-2019 • Last Date for Receipt of Applications: 16-04-2019 till 18.00 Hours. -

Chapter-Iv Revolt of 1857 and Muslims in Haryana

CHAPTER-IV REVOLT OF 1857 AND MUSLIMS IN HARYANA In order to understand the regional and micro-level behaviour and attitude of Muslim Community towards British Raj or Western Culture it is necessary to have a separate chapter in this study. Hence this chapter on the great Revolt deserve its place in the present study. The great Revolt proved to be a perfect and representative historical event to analyze the general political attitude of various sections of the Muslim community of Haryana. The Sepoys, the people and feudal chiefs all took part in this revolt in large number. Their participation and struggle displayed a general attitude of confrontation towards British Raj. The study regarding Haryana began with the regional description, structural understanding of the society of Haryana, general survey of revolt, the role of the princely states and masses and ends with the inference that muslims took part in this great revolt with vigour and enthusiasm and suffered more than any other community of Haryana. The present Haryana region’s political history may be attributed to the very beginning of the nineteenth century when the British East India Company came to the scene. The Marathas who had over the territory of Haryana were ousted from here by the British. By the treaty of Surji Anjangaon on 30 December, 1803 between Daulat Rao Sindhia and the British, the territory of Haryana passed on the British East India Company. The East India Company assumed the direct control of Delhi, Panipat, Sonepat, Samalkha, Ganaur, Palam, Nuh, Hathin, Bhoda, Sohna, Rewari, Indri, Palwal, Nagina and Ferozepur Zhrka and appointed a resident on behalf of the Governor General.