From Albums to Images Studio Ghibli's Image Albums and Their Impact On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirited Away Study Guide

Spirited Away Directed by Hayao Miyazki This study guide suggests cross-curricular activities based on the film Spirited Away by Hanoko Miyazaki. The activities seek to complement and extend the enjoyment of watching the film, while at the same time meeting some of the requirements of the National Curriculum and Scottish Guidelines. The subject area the study guide covers includes Art and Design, Music, English, Citizenship, People in Society, Geography and People and Places. The table below specifies the areas of the curriculum that the activities cover National Curriculum Scottish Guidelines Subject Level Subject Level Animation Art +Design KS2 2 C Art + Investigating Visually and 3 A+B Design Reading 5 A-D Using Media – Level B-E Communicating Level A Evaluating/Appreciating Level D Sound Music KS2 3 A Music Investigating: exploring 4A-D sound Level A-C Evaluating/Appreciating Level A,C,D Setting & English KS2 Reading English Reading Characters 2 A-D Awareness of genre 4 C-I Level B-D Knowledge about language level C-D Setting & Citizenship KS2 1 A-C People People & Needs in Characters 4 A+B In Society Society Level A Japan Geography KS2 2 E-F People & Human Environment 3 A-G Places Level A-B 5 A-B Human Physical 7 C Interaction Level A-D Synopsis When we first meet ten year-old Chihiro she is unhappy about moving to a new town with her parents and leaving her old life behind. She is moody, whiney and miserable. On the way to their new house, the family get lost and find themselves in a deserted amusement park, which is actually a mythical world. -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

La Notion ''D'habiter'' Ou Comment Aborder En Classe Les Spécificités

La notion ”d’habiter” ou comment aborder en classe les spécificités des occupations géographiques humaines à travers l’animation japonaise Audrey Jaux To cite this version: Audrey Jaux. La notion ”d’habiter” ou comment aborder en classe les spécificités des occupations géographiques humaines à travers l’animation japonaise. Education. 2017. hal-02386034 HAL Id: hal-02386034 https://hal-univ-fcomte.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02386034 Submitted on 29 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Mémoire présenté pour l’obtention du Grade de MASTER “Métiers de l’Enseignement, de l’Education et de la Formation” Mention 1er Degré Professeur des Ecoles Sur le thème La notion « d’habiter », ou comment aborder en classe les spécificités des occupations géographiques humaines à travers l’animation Japonaise. Projet présenté par Audrey Jaux Directeur Professeur : Michel Vrac (Ecole supérieure du professorat et de l'éducation. ESPE Montjoux) Numéro CNU : 23 Année universitaire 2016-2017 1 Remerciements : A Michel VRAC pour la richesse de documentation qu’il m’a proposé et pour sa disponibilité et son aide. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

(WHEN MARNIE WAS THERE) Is a Fourth Quarter 2017 LVCA Dvd

OMOIDE NO MÂNÎ (WHEN MARNIE WAS THERE) is a Fourth Quarter 2017 LVCA dvd donation to the Hugh Stouppe Memorial Library of the Heritage United Methodist Church of Ligonier, Pennsylvania. Here’s Kino Ken’s review of that mystical animation from Japan. 16 of a possible 20 points **** of a possible ***** Japan 2014 color 103 minutes feature animation fantasy dubbed in English Studio Ghibli / Toho Company /Dentsu / Hakuhodo DY Media Partners Producers: Yoshiaki Nishimura, Koji Hoshino, Geoffrey Wexler (English version), Toshio Suzuki Key: *indicates outstanding technical achievement or performance (j) designates a juvenile performer Points: Direction: Hiromasa Yonebayashi 0 Editing: Rie Matsubara 2 Photography: Atsushi Okui 2 Lighting 2 Animation: Masashi Ando (Animation Director) 1 Screenplay: Keiko Niwa, Masashi Ando, and Hiromasa Yonebayashi based on the novel by Joan Robinson 2 Music: Takatsugu Muramatsu, Priscilla Ahn (theme music) Francisco Tarriega (“Valse in La Mayor” from Recuerdos de la Alhambra) 2 Production Design: Yohei Taneda Character Design: Masashi Ando 2 Sound: Eriko Kimura, Jamie Simone (English Version) Sound Direction: Koji Kasamatsu 1 Voices Acting 2 Creativity 16 total points English Voices Cast: Ava Acres (Sayaka), Kathy Bates (Mrs. Kadoya), Taylor Autumn Bertman (j) (Young Marnie), Mila Brener (j) (Young Hisako), Ellen Burstyn (Nan), Geena Davis (Yoriko Sasaki), Grey Griffin (Setsu Oiwa), Catherine O’Hara (Elderly Lady), Takuma Oroo (Neighborhood Association Officer), John Reilly (Kiyomasa Oiwa), Raini Rodriguez (Nobuko -

How the Filmography of Hayao Miyazaki Subverts Nation Branding and Soft Power

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by University of Tasmania Open Access Repository 1 Wings and Freedom, Spirit and Self: How the Filmography of Hayao Miyazaki Subverts Nation Branding and Soft Power Shadow (BA Hons) 195408 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters of Journalism, Media and Communications University of Tasmania June, 2015 2 Declaration of Originality: This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 Authority of Access: This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 3 Declaration of Copy Editing: Professional copy was provided by Walter Leggett to amend issues with consistency, spelling and grammar. No other content was altered by Mr Leggett and editing was undertaken under the consent and recommendation of candidate’s supervisors. X Shadow Date: 6/10/2015 4 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 ............................................................................................................................. -

CH Rental 5/27/15 10:38 AM Page 1

06-14 DCINY_CH Rental 5/27/15 10:38 AM Page 1 Sunday Afternoon, June 14, 2015, at 2:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Iris Derke, Co-Founder and General Director Jonathan Griffith, Co-Founder and Artistic Director presents Future Vibrations THE CENTRAL OREGON YOUTH ORCHESTRA AMY GOESER KOLB, Founder and Executive Director JULIA BASTUSCHECK, Director EDDY ROBINSON, Director GEORGE GERSHWIN An American in Paris arr. John Whitney CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS Bacchanale from Samson and Delilah arr. Merle J. Isaac CHRISTOPHER TIN Iza Ngomso (New York Premiere) PETER ILYICH 1812 Overture , Op. 49 TCHAIKOVSKY arr. Jerry Brubaker OTTORINO RESPIGHI Pines of Rome (Pines of the Appian Way) arr. Stephen Bulla Brief Pause PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. 06-14 DCINY_CH Rental 5/27/15 10:38 AM Page 2 VANCOUVER POPS SYMPHONY TOM KUO, Director JOE HISAISHI My Neighbor Totoro JOHN POWELL How to Train Your Dragon MICHAEL GIACCHINO Star Trek: Into Darkness ALAN MENKEN Aladdin Intermission MUSIC FOR TREBLE VOICES FRANCISCO J. NÚÑEZ, Guest Conductor JON HOLDEN, Piano DISTINGUISHED CONCERTS SINGERS INTERNATIONAL WOLFGANG AMADEUS Papageno-Papagena Duet MOZART arr. Doreen Rao FRANCISCO J. NÚÑEZ Misa Pequeña para Niños (A Children’s Mass) I. Señor, Ten Piedad II. Gloria a Dios III. Creo en Dios IV. Santo, Santo, Santo V. Cordero de Dios SLOVAKIAN FOLK SONG Dobrú Noc (Good Night) arr. Victor C. Johnson JIM PAPOULIS Sih’r Khalaq (Creative Magic) arr. Susan Brumfield Love Lies Under the Old Oak Tree FRANCISCO J. NÚÑEZ Pinwheels FRANCISCO J. NÚÑEZ La Sopa de Isabel (Elizabeth’s Soup) We Want To Hear From You! Upload your intermission photos and post-show feedback to Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook! #FutureVibrations @DCINY DCINY thanks its kind sponsors and partners in education: Artist Travel Consultants, VH-1 Save the Music, Education Through Music, High 5, WQXR. -

Joe Hisaishi Symphonic Concert Music from the Studio Ghibli Films of Hayao Miyazaki BR AVO 26-28 April 2018

Joe Hisaishi Symphonic Concert Music from the Studio Ghibli Films of Hayao Miyazaki BR AVO 26-28 April 2018 Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Joe Hisaishi conductor and piano Mai Fujisawa vocals Antoinette Halloran soprano Ken Murray mandolin Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Chorus In April 2018, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra presented Joe Hisaishi Symphonic Concert: Music from the Studio Ghibli Films of Hayao Miyazaki, conducted by the composer Joe Joe Hisaishi conducts at Joe Hisaishi Symphonic Concert: Music from Hisaishi in his first Australian performances. the Studio Ghibli Films of Hayao Miyazaki at Hamer Hall To the delight of Victorian audiences and those who travelled interstate and overseas for this Australian premiere, the four 4 CONCERTS sell-out concerts in Hamer Hall featured the extraordinary 26 APRIL 27 APRIL 28 APRIL scores by Hisaishi, while montages from the renowned Miyazaki films including Howl’s Moving Castle, Princess Mononoke, My Neighbor Totoro and the Oscar-winning Spirited Away were played on screen above the MSO. His Excellency Kazuyoshi Matsunaga, Consul-General of Japan in Melbourne welcomed audiences to this premiere Venue cultural event and said he was honoured that Melbourne ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE and its world-class orchestra had been chosen for the first HAMER HALL performance of this concert in the Southern Hemisphere. A pre-concert event was hosted by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in recognition of Australia’s strong relationship with Japan – a trusted partner with shared values 10,500 and interests. “ In the spirit of ‘Australia now 2018’, the Melbourne Symphony WAITLIST Orchestra presenting the Studio Ghibli Concert showcases creative collaboration and highlights the strength of our enduring relationship with Japan.” 9,257 – H.E. -

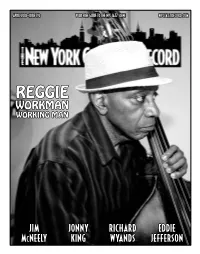

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Hayao Miyazaki Film

A HAYAO MIYAZAKI FILM ORIGINAL STORY AND SCREENPLAY WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY HAYAO MIYAZAKI MUSIC BY JOE HISAISHI THEME SONGS PERFORMED BY MASAKO HAYASHI AND FUJIOKA FUJIMAKI & NOZOMI OHASHI STUDIO GHIBLI NIPPON TELEVISION NETWORK DENTSU HAKUHODO DYMP WALT DISNEY STUDIOS HOME ENTERTAINMENT MITSUBISHI AND TOHO PRESENT A STUDIO GHIBLI PRODUCTION - PONYO ON THE CLIFF BY THE SEA EXECUTIVE PRODUCER KOJI HOSHINO PRODUCED BY TOSHIO SUZUKI © 2008 Nibariki - GNDHDDT Studio Ghibli, Nippon Television Network, Dentsu, Hakuhodo DYMP, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, Mitsubishi and Toho PRESENT PONYO ON THE CLIFF BY THE SEA WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY HAYAO MIYAZAKI Running time: 1H41 – Format: 1.85:1 Sound: Dolby Digital Surround EX - DTS-ES (6.1ch) INTERNATIONAL PRESS THE PR CONTACT [email protected] Phil Symes TEL 39 346 336 3406 Ronaldo Mourao TEL +39 346 336 3407 WORLD SALES wild bunch Vincent Maraval TEL +33 6 11 91 23 93 E [email protected] Gaël Nouaille TEL +33 6 21 23 04 72 E [email protected] Carole Baraton / Laurent Baudens TEL +33 6 70 79 05 17 E [email protected] Silvia Simonutti TEL +33 6 20 74 95 08 E [email protected] PARIS OFFICE 99 Rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris - France TEL +33 1 53 01 50 30 FAX +33 1 53 01 50 49 [email protected] PLEASE NOTE: High definition images can be downloaded from the ‘press’ section of http://www.wildbunch.biz SYNOPSIS CAST A small town by the sea. Lisa Tomoko Yamaguchi Koichi Kazushige Nagashima Five year-old Sosuke lives high on a cliff overlooking Gran Mamare Yuki Amami the Inland Sea. -

Haruomi Hosono, Shigeru Suzuki, Tatsuro Yamashita

Haruomi Hosono Pacific mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz Album: Pacific Country: Japan Released: 2013 Style: Fusion, Electro MP3 version RAR size: 1618 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1203 mb WMA version RAR size: 1396 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 218 Other Formats: AA ASF VQF APE AIFF WMA ADX Tracklist Hide Credits 最後の楽園 1 Bass, Keyboards – Haruomi HosonoDrums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Ryuichi 4:03 SakamotoWritten-By – Haruomi Hosono コーラル・リーフ 2 3:45 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki ノスタルジア・オブ・アイランド~パート1:バード・ウィンド/パート2:ウォーキング・オン・ザ・ビーチ 3 9:37 Keyboards – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Tatsuro Yamashita スラック・キー・ルンバ 4 Bass, Guitar, Percussion – Haruomi HosonoDrums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Ryuichi 3:02 SakamotoWritten-By – Haruomi Hosono パッション・フラワー 5 3:35 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki ノアノア 6 4:10 Piano – Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – Shigeru Suzuki キスカ 7 5:26 Written-By – Tatsuro Yamashita Cosmic Surfin' 8 Drums – Yukihiro TakahashiKeyboards – Haruomi Hosono, Ryuichi SakamotoWritten-By – 5:07 Haruomi Hosono Companies, etc. Record Company – Sony Music Direct (Japan) Inc. Credits Remastered By – Tetsuya Naitoh* Notes 2013 reissue. Album originally released in 1978. Track 8 is a rare early version of the Yellow Magic Orchestra track. Translated track titles: 01: The Last Paradise 02: Coral Reef 03: Nostalgia of Island (Part 1: Wind Bird, Part 2: Walking on the Beach 04: Slack Key Rumba 05: Passion Flower 06: Noanoa 07: Kiska Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4582290393407 -

A Voice Against War

STOCKHOLMS UNIVERSITET Institutionen för Asien-, Mellanöstern- och Turkietstudier A Voice Against War Pacifism in the animated films of Miyazaki Hayao Kandidatuppsats i japanska VT 2018 Einar Schipperges Tjus Handledare: Ida Kirkegaard Innehållsförteckning Annotation ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aim of the study ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Material ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Research question .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Theory ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.1 Textual analysis ...................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.2 Theory of animation, definition of animation ........................................................................ 6 1.5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................