Arxiv:1706.00480V2 [Math.CO] 4 Oct 2017 Where N Ekyicesn Euneof Sequence Increasing Weakly Any Ihvrie in Vertices with Sas Atc Oyoe Ntecs F∆ of Case the in Polytope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

Zero Displacement Ternary Number System: the Most Economical Way of Representing Numbers

Revista de Ciências da Computação, Volume III, Ano III, 2008, nº3 Zero Displacement Ternary Number System: the most economical way of representing numbers Fernando Guilherme Silvano Lobo Pimentel , Bank of Portugal, Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper concerns the efficiency of number systems. Following the identification of the most economical conventional integer number system, from a solid criteria, an improvement to such system’s representation economy is proposed which combines the representation efficiency of positional number systems without 0 with the possibility of representing the number 0. A modification to base 3 without 0 makes it possible to obtain a new number system which, according to the identified optimization criteria, becomes the most economic among all integer ones. Key Words: Positional Number Systems, Efficiency, Zero Resumo Este artigo aborda a questão da eficiência de sistemas de números. Partindo da identificação da mais económica base inteira de números de acordo com um critério preestabelecido, propõe-se um melhoramento à economia de representação nessa mesma base através da combinação da eficiência de representação de sistemas de números posicionais sem o zero com a possibilidade de representar o número zero. Uma modificação à base 3 sem zero permite a obtenção de um novo sistema de números que, de acordo com o critério de optimização identificado, é o sistema de representação mais económico entre os sistemas de números inteiros. Palavras-Chave: Sistemas de Números Posicionais, Eficiência, Zero 1 Introduction Counting systems are an indispensable tool in Computing Science. For reasons that are both technological and user friendliness, the performance of information processing depends heavily on the adopted numbering system. -

Duodecimal Bulletin Vol

The Duodecimal Bulletin Bulletin Duodecimal The Vol. 4a; № 2; Year 11B6; Exercise 1. Fill in the missing numerals. You may change the others on a separate sheet of paper. 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 ■ Volume Volume nada 3 zero. one. two. three.trio 3 1 1 4 a ; (58.) 1 1 2 3 2 2 ■ Number Number 2 sevenito four. five. six. seven. 2 ; 1 ■ Whole Number Number Whole 2 2 1 2 3 99 3 ; (117.) eight. nine. ________.damas caballeros________. All About Our New Numbers 99;Whole Number ISSN 0046-0826 Whole Number nine dozen nine (117.) ◆ Volume four dozen ten (58.) ◆ № 2 The Dozenal Society of America is a voluntary nonprofit educational corporation, organized for the conduct of research and education of the public in the use of base twelve in calculations, mathematics, weights and measures, and other branches of pure and applied science Basic Membership dues are $18 (USD), Supporting Mem- bership dues are $36 (USD) for one calendar year. ••Contents•• Student membership is $3 (USD) per year. The page numbers appear in the format Volume·Number·Page TheDuodecimal Bulletin is an official publication of President’s Message 4a·2·03 The DOZENAL Society of America, Inc. An Error in Arithmetic · Jean Kelly 4a·2·04 5106 Hampton Avenue, Suite 205 Saint Louis, mo 63109-3115 The Opposed Principles · Reprint · Ralph Beard 4a·2·05 Officers Eugene Maxwell “Skip” Scifres · dsa № 11; 4a·2·08 Board Chair Jay Schiffman Presenting Symbology · An Editorial 4a·2·09 President Michael De Vlieger Problem Corner · Prof. -

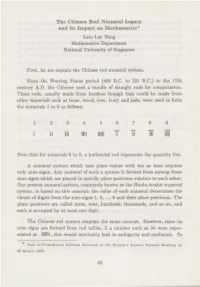

The Chinese Rod Numeral Legacy and Its Impact on Mathematics* Lam Lay Yong Mathematics Department National University of Singapore

The Chinese Rod Numeral Legacy and its Impact on Mathematics* Lam Lay Yong Mathematics Department National University of Singapore First, let me explain the Chinese rod numeral system. Since the Warring States period {480 B.C. to 221 B.C.) to the 17th century A.D. the Chinese used a bundle of straight rods for computation. These rods, usually made from bamboo though they could be made from other materials such as bone, wood, iron, ivory and jade, were used to form the numerals 1 to 9 as follows: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 II Ill Ill I IIIII T II Note that for numerals 6 to 9, a horizontal rod represents the quantity five. A numeral system which uses place values with ten as base requires only nine signs. Any numeral of such a system is formed from among these nine signs which are placed in specific place positions relative to each other. Our present numeral system, commonly known as the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, is based on this concept; the value of each numeral determines the choice of digits from the nine signs 1, 2, ... , 9 anq their place positions. The place positions are called units, tens, hundreds, thousands, and so on, and each is occupied by at most one digit. The Chinese rod system employs the same concept. However, since its nine signs are formed from rod tallies, if a number such as 34 were repre sented as Jll\IU , this would inevitably lead to ambiguity and confusion. To * Text of Presidential Address delivered at the Society's Annual General Meeting on 20 March 1987. -

Inventing Your Own Number System

Inventing Your Own Number System Through the ages people have invented many different ways to name, write, and compute with numbers. Our current number system is based on place values corresponding to powers of ten. In principle, place values could correspond to any sequence of numbers. For example, the places could have values corre- sponding to the sequence of square numbers, triangular numbers, multiples of six, Fibonacci numbers, prime numbers, or factorials. The Roman numeral system does not use place values, but the position of numerals does matter when determining the number represented. Tally marks are a simple system, but representing large numbers requires many strokes. In our number system, symbols for digits and the positions they are located combine to represent the value of the number. It is possible to create a system where symbols stand for operations rather than values. For example, the system might always start at a default number and use symbols to stand for operations such as doubling, adding one, taking the reciprocal, dividing by ten, squaring, negating, or any other specific operations. Create your own number system. What symbols will you use for your numbers? How will your system work? Demonstrate how your system could be used to perform some of the following functions. • Count from 0 up to 100 • Compare the sizes of numbers • Add and subtract whole numbers • Multiply and divide whole numbers • Represent fractional values • Represent irrational numbers (such as π) What are some of the advantages of your system compared with other systems? What are some of the disadvantages? If you met aliens that had developed their own number system, how might their mathematics be similar to ours and how might it be different? Make a list of some math facts and procedures that you have learned. -

Number Systems and Radix Conversion

Number Systems and Radix Conversion Sanjay Rajopadhye, Colorado State University 1 Introduction These notes for CS 270 describe polynomial number systems. The material is not in the textbook, but will be required for PA1. We humans are comfortable with numbers in the decimal system where each po- sition has a weight which is a power of 10: units have a weight of 1 (100), ten’s have 10 (101), etc. Even the fractional apart after the decimal point have a weight that is a (negative) power of ten. So the number 143.25 has a value that is 1 ∗ 102 + 4 ∗ 101 + 3 ∗ 0 −1 −2 2 5 10 + 2 ∗ 10 + 5 ∗ 10 , i.e., 100 + 40 + 3 + 10 + 100 . You can think of this as a polyno- mial with coefficients 1, 4, 3, 2, and 5 (i.e., the polynomial 1x2 + 4x + 3 + 2x−1 + 5x−2+ evaluated at x = 10. There is nothing special about 10 (just that humans evolved with ten fingers). We can use any radix, r, and write a number system with digits that range from 0 to r − 1. If our radix is larger than 10, we will need to invent “new digits”. We will use the letters of the alphabet: the digit A represents 10, B is 11, K is 20, etc. 2 What is the value of a radix-r number? Mathematically, a sequence of digits (the dot to the right of d0 is called the radix point rather than the decimal point), : : : d2d1d0:d−1d−2 ::: represents a number x defined as follows X i x = dir i 2 1 0 −1 −2 = ::: + d2r + d1r + d0r + d−1r + d−2r + ::: 1 Example What is 3 in radix 3? Answer: 0.1. -

A Ternary Arithmetic and Logic

Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2010 Vol I WCE 2010, June 30 - July 2, 2010, London, U.K. A Ternary Arithmetic and Logic Ion Profeanu which supports radical ontological dualism between the two Abstract—This paper is only a chapter, not very detailed, of eternal principles, Good and Evil, which oppose each other a larger work aimed at developing a theoretical tool to in the course of history, in an endless confrontation. A key investigate first electromagnetic fields but not only that, (an element of Manichean doctrine is the non-omnipotence of imaginative researcher might use the same tool in very unusual the power of God, denying the infinite perfection of divinity areas of research) with the stated aim of providing a new perspective in understanding older or recent research in "free that has they say a dual nature, consisting of two equal but energy". I read somewhere that devices which generate "free opposite sides (Good-Bad). I confess that this kind of energy" works by laws and principles that can not be explained dualism, which I think is harmful, made me to seek another within the framework of classical physics, and that is why they numeral system and another logic by means of which I will are kept far away from public eye. So in the absence of an praise and bring honor owed to God's name; and because adequate theory to explain these phenomena, these devices can God is One Being in three personal dimensions (the Father, not reach the design tables of some plants in order to produce them in greater number. -

Scalability of Algorithms for Arithmetic Operations in Radix Notation∗

Scalability of Algorithms for Arithmetic Operations in Radix Notation∗ Anatoly V. Panyukov y Department of Computational Mathematics and Informatics, South Ural State University, Chelyabinsk, Russia [email protected] Abstract We consider precise rational-fractional calculations for distributed com- puting environments with an MPI interface for the algorithmic analysis of large-scale problems sensitive to rounding errors in their software imple- mentation. We can achieve additional software efficacy through applying heterogeneous computer systems that execute, in parallel, local arithmetic operations with large numbers on several threads. Also, we investigate scalability of the algorithms for basic arithmetic operations and methods for increasing their speed. We demonstrate that increased efficacy can be achieved of software for integer arithmetic operations by applying mass parallelism in het- erogeneous computational environments. We propose a redundant radix notation for the construction of well-scaled algorithms for executing ba- sic integer arithmetic operations. Scalability of the algorithms for integer arithmetic operations in the radix notation is easily extended to rational- fractional arithmetic. Keywords: integer computer arithmetic, heterogeneous computer system, radix notation, massive parallelism AMS subject classifications: 68W10 1 Introduction Verified computations have become indispensable tools for algorithmic analysis of large scale unstable problems (see e.g., [1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10]). Such computations require spe- cific software tools; in this connection, we mention that our library \Exact computa- tion" [11] provides appropriate instruments for implementation of such computations ∗Submitted: January 27, 2013; Revised: August 17, 2014; Accepted: November 7, 2014. yThe author was supported by the Federal special-purpose program "Scientific and scientific-pedagogical personnel of innovation Russia", project 14.B37.21.0395. -

Binary Numbers

Binary Numbers X. Zhang Fordham Univ. 1 Numeral System ! A way for expressing numbers, using symbols in a consistent manner. ! ! "11" can be interpreted differently:! ! in the binary symbol: three! ! in the decimal symbol: eleven! ! “LXXX” represents 80 in Roman numeral system! ! For every number, there is a unique representation (or at least a standard one) in the numeral system 2 Modern numeral system ! Positional base 10 numeral systems ! ◦ Mostly originated from India (Hindu-Arabic numeral system or Arabic numerals)! ! Positional number system (or place value system)! ◦ use same symbol for different orders of magnitude! ! For example, “1262” in base 10! ◦ the “2” in the rightmost is in “one’s place” representing “2 ones”! ◦ The “2” in the third position from right is in “hundred’s place”, representing “2 hundreds”! ◦ “one thousand 2 hundred and sixty two”! ◦ 1*103+2*102+6*101+2*100 3 Modern numeral system (2) ! In base 10 numeral system! ! there is 10 symbols: 0, 1, 2, 3, …, 9! ! Arithmetic operations for positional system is simple! ! Algorithm for multi-digit addition, subtraction, multiplication and division! ! This is a Chinese Abacus (there are many other types of Abacus in other civilizations) dated back to 200 BC 4 Other Positional Numeral System ! Base: number of digits (symbols) used in the system.! ◦ Base 2 (i.e., binary): only use 0 and 1! ◦ Base 8 (octal): only use 0,1,…7! ◦ Base 16 (hexadecimal): use 0,1,…9, A,B,C,D,E,F! ! Like in decimal system, ! ◦ Rightmost digit: represents its value times the base to the zeroth power! -

Fibonacci P-Codes and Codes of the “Golden” P-Proportions: New Informational and Arithmetical Foundations of Computer Scienc

British Journal of Mathematics & Computer Science 17(1): 1-49, 2016, Article no.BJMCS.25969 ISSN: 2231-0851 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Fibonacci p-codes and Codes of the “Golden” p-proportions: New Informational and Arithmetical Foundations of Computer Science and Digital Metrology for Mission-Critical Applications Alexey Stakhov1* 1International Club of the Golden Section, Canada. Author’s contribution The sole author designed, analyzed and interpreted and prepared the manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/BJMCS/2016/25969 Editor(s): (1) Wei-Shih Du, Department of Mathematics, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Taiwan. Reviewers: (1) Santiago Tello-Mijares, Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Lerdo, Mexico. (2) Danyal Soybas, Erciyes University, Turkey. (3) Manuel Alberto M. Ferreira, ISCTE-IUL, Portugal. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/14921 Received: 28th March 2016 Accepted: 2nd June 2016 Original Research Article Published: 7th June 2016 _______________________________________________________________________________ Abstract In the 70s and 80s years of the past century, the new positional numeral systems, called Fibonaссi p-codes and codes of the golden p-proportions, as new informational and arithmetical foundations of computer science and digital metrology, was considered as one of the most important directions of Soviet computer science and digital metrology for mission-critical applications. The main advantage of this direction was to improve the information reliability of computer and measuring systems. This direction has been patented abroad widely (more than 60 patents of US, Japan, England, France, Germany, Canada and other countries). Theoretical basis of this direction have been described in author’s books "Introduction into the Algorithmic Measurement Theory" (1977), and "Codes of the Golden Proportion" (1984). -

Number Systems Radix Number Systems Radix Number Systems

Number Systems 4/26/2010 Number Systems Radix Number Systems binary, octal, and hexadecimal numbers basic idea of a radix number system ‐‐ why used how do we count: conversions, including to/from decimal didecimal : 10 dis tinc t symblbols, 0‐9 negative binary numbers when we reach 9, we repeat 0‐9 with 1 in front: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, 10,11,12,13, …, 19 floating point numbers then with a 2 in front, etc: 20, 21, 22, 23, …, 29 character codes until we reach 99 then we repeat everything with a 1 in the next position: 100, 101, …, 109, 110, …, 119, …, 199, 200, … other number systems follow the same principle with a different base (radix) Lubomir Bic 1 Lubomir Bic 2 Radix Number Systems Radix Number Systems octal: we have only 8 distinct symbols: 0‐7 binary: we have only 2 distinct symbols: 0, 1 when we reach 7, we repeat 0‐7 with 1 in front why?: digital computer can only represent 0 and 1 012345670,1,2,3,4,5,6,7, 10,11,12,13, …, 17 when we reach 1, we repeat 0‐1 with 1 in front then with a 2 in front, etc: 20, 21, 22, 23, …, 27 0,1, 10,11 until we reach 77 then we repeat everything with a 1 in the next position: then we repeat everything with a 1 in the next position: 100, 101, 110, 111, 1000, 1001, 1010, 1011, 1100, … 100, 101, …, 107, 110, …, 117, …, 177, 200, … decimal to binary correspondence: decimal to octal correspondence: D 01234 5 6 7 8 9 101112… D 0 1 … 7 8 9 10 11 … 15 16 17 … 23 24 … 63 64 … B 0 1 10 11 100 101 110 111 1000 1001 1010 1011 1100 … O 0 1 … 7 10 11 12 13 … 17 20 21 … 27 30 … 77 100 … -

![United States Patent 15 3,700,872 May [45] Oct](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3302/united-states-patent-15-3-700-872-may-45-oct-1053302.webp)

United States Patent 15 3,700,872 May [45] Oct

United States Patent 15 3,700,872 May [45] Oct. 24, 1972 54 RADX CONVERSON CRCUTS Primary Examiner - Maynard R. Wilbur Assistant Examiner- Leo H. Boudreau (72) Inventor: Frederick T. May, Austin,Tex. Attorney-Hanifin and Clark and D. Kendall Cooper (73) Assignee: International Business Corporation, Armonk, N.Y. 57) ABSTRACT 22 Filed: Aug. 22, 1969 Data conversion circuits with optimized common hardware convert numbers expressed in a first radix C (21) Appl. No.: 852,272 to other radices n1, m2, etc., with the mode of opera Related U.S. Application Data tion being controlled to establish a radix C to radix ml conversion in one mode, a radix C to radix n2 conver 63 Continuation-in-part of Ser. No. 517,764, Dec. sion in another mode, etc., on a selective basis, as 30, 1965, abandoned. desired. In a first embodiment, numbers represented in a binary (base 2) radix Care converted to a base 10 52 U.S. Ct.............. 235/155,340/347 DD, 235/165 (n1) or base 12(m2) representation. In a second em 51 int. Cl.............................................. HO3k 13/24 bodiment, numbers stored in a ternary (base 3) radix 58 Field of Search......... 340/347 DD; 235/155, 165 C representation are converted to a base 12 (n1) or base 10 (m2) representation. The circuits are 56 References Cited predicated upon recognition of the fact that a number UNITED STATES PATENTS represented in a first radix can be converted readily to a second radix using shared hardware if the following 2,620,974 12/1952 Waltat.................... 23.5/155 X equation is satisfied: 2,831,179 4/1958 Wright et al..........