Getting to Grips with Power Can Ngos Improve Justice in Bangladesh?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madaripur District

GEO Code based Unique Water Point ID Madaripur District Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE) June, 2018 How to Use This Booklet to Assign Water Point Identification Code: Assuming that a contractor or a driller is to install a Shallow Tube Well with No. 6 Pump in SULTANPUR village BEMARTA union of BAGERHAT SADAR uapzila in BAGERHAR district. This water point will be installed in year 2010 by a GOB-Unicef project. The site of installation is a bazaar. The steps to assign water point code (Figure 1) are as follows: Y Y Y Y R O O W W Z Z T T U U U V V V N N N Figure 1: Format of Geocode Based Water Point Identification Code Step 1: Write water point year of installation as the first 4 digits indicated by YYYY. For this example, it is 2010. Step 2: Select land use type (R) code from Table R (page no. 4). For this example, a bazaar for rural commercial purpose, so it is 4. Step 3: Select water point type of ownership (OO) from Table OO (page no. 4) . For this example, it is 05. Step 4: Select water point type (WW) code from Table WW (page no. 5). For this example, water point type is Shallow Tube Well with No. 6 Pump. Therefore its code is 01. Step 5: Assign district (ZZ), upazila (TT) and union (UUU) GEO Code for water point. The GEO codes are as follows: for BAGERGAT district, ZZ is 01; for BAGERHAR SADAR upazila, TT is 08; and for BEMARTA union, UUU is 151. -

Esdo Profile 2021

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE 2021 Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) 1. BACKGROUND Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

Esdo Profile

ECO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION (ESDO) ESDO PROFILE Head Office Address: Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) Collegepara (Gobindanagar), Thakurgaon-5100, Thakurgaon, Bangladesh Phone:+88-0561-52149, +88-0561-61614 Fax: +88-0561-61599 Mobile: +88-01714-063360, +88-01713-149350 E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd Dhaka Office: ESDO House House # 748, Road No: 08, Baitul Aman Housing Society, Adabar,Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-58154857, Mobile: +88-01713149259, Email: [email protected] Web: www.esdo.net.bd 1 Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) 1. Background Eco-Social Development Organization (ESDO) has started its journey in 1988 with a noble vision to stand in solidarity with the poor and marginalized people. Being a peoples' centered organization, we envisioned for a society which will be free from inequality and injustice, a society where no child will cry from hunger and no life will be ruined by poverty. Over the last thirty years of relentless efforts to make this happen, we have embraced new grounds and opened up new horizons to facilitate the disadvantaged and vulnerable people to bring meaningful and lasting changes in their lives. During this long span, we have adapted with the changing situation and provided the most time-bound effective services especially to the poor and disadvantaged people. Taking into account the government development policies, we are currently implementing a considerable number of projects and programs including micro-finance program through a community focused and people centered approach to accomplish government’s development agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN as a whole. -

Ministry of Food and Disaster Management

Situation Report Disaster Management Information Centre Disaster Management Bureau (DMB) Ministry of Food and Disaster Management Disaster Management and Relief Bhaban (6th Floor) 92-93 Mohakhali C/A, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh Phone: +88-02-9890937, Fax: +88-02-9890854 Email: [email protected] ,H [email protected] Web: http://www.cdmp.org.bdH ,H www.dmb.gov.bd Emergency Flood Situation Title: Emergency Bangladesh Location: 20°22'N-26°36'N, 87°48'E-92°41'E, Covering From: TUE-02-SEP-2008:1200 Period: To: WED-03-SEP-2008:1200 Transmission Date/Time: WED-03-SEP-2008:1500 Prepared by: DMIC, DMB Flood, Rainfall, River Situation and Summary of Water Levels Current Situation: Flood situation in the north and north-eastern part of the country is likely to improve further. The mighty Brahmaputra – Jamuna started falling. More low lying areas in some districts are likely to inundate by next 24-48 hours. FLOOD, RAINFALL AND RIVER SITUATION SUMMARY (as on September 3, 2008) Flood Outlook • Flood situation in the north and north-eastern part of the country is likely to improve further in the next 24- 48 hrs. • The mighty Brahmaputra –Jamuna started falling at all the monitoring stations and is likely to improve further in the next 24-48 hrs. • The confluence of both the rivers (the Padma at Goalundo & Bhagyakul) will continue rising at moderate rate for next 2-3 days. • More low lying areas in the districts of Chandpur, Serajganj, Tangail, Munshiganj, Manikganj, Faridpur, Madaripur, Shariatpur, Dohar & Nawabganj of Dhaka district, Shibganj & Sadar of Chapai-Nawabganj district is likely to inundate by next 24-48 hours. -

“Crossfire:” Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh's Rapid

Bangladesh HUMAN “Crossfire” RIGHTS Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion WATCH “Crossfire” Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-767-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2011 ISBN 1-56432-767-1 “Crossfire” Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion Map of Bangladesh ........................................................................................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations: .............................................................................................................. 9 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 11 I. Killings and Other Cases of Abuse by RAB Since the Awami League Government Came to Power in 2009 ................................................................................................................................. -

List of 100 Bed Hospital

List of 100 Bed Hospital No. of Sl.No. Organization Name Division District Upazila Bed 1 Barguna District Hospital Barisal Barguna Barguna Sadar 100 2 Barisal General Hospital Barisal Barishal Barisal Sadar (kotwali) 100 3 Bhola District Hospital Barisal Bhola Bhola Sadar 100 4 Jhalokathi District Hospital Barisal Jhalokati Jhalokati Sadar 100 5 Pirojpur District Hospital Barisal Pirojpur Pirojpur Sadar 100 6 Bandarban District Hospital Chittagong Bandarban Bandarban Sadar 100 7 Comilla General Hospital Chittagong Cumilla Comilla Adarsha Sadar 100 8 Khagrachari District Hospital Chittagong Khagrachhari Khagrachhari Sadar 100 9 Lakshmipur District Hospital Chittagong Lakshmipur Lakshmipur Sadar 100 10 Rangamati General Hospital Chittagong Rangamati Rangamati Sadar Up 100 11 Faridpur General Hospital Dhaka Faridpur Faridpur Sadar 100 12 Madaripur District Hospital Dhaka Madaripur Madaripur Sadar 100 13 Narayanganj General (Victoria) Hospital Dhaka Narayanganj Narayanganj Sadar 100 14 Narsingdi District Hospital Dhaka Narsingdi Narsingdi Sadar 100 15 Rajbari District Hospital Dhaka Rajbari Rajbari Sadar 100 16 Shariatpur District Hospital Dhaka Shariatpur Shariatpur Sadar 100 17 Bagerhat District Hospital Khulna Bagerhat Bagerhat Sadar 100 18 Chuadanga District Hospital Khulna Chuadanga Chuadanga Sadar 100 19 Jhenaidah District Hospital Khulna Jhenaidah Jhenaidah Sadar 100 20 Narail District Hospital Khulna Narail Narail Sadar 100 21 Satkhira District Hospital Khulna Satkhira Satkhira Sadar 100 22 Netrokona District Hospital Mymensingh Netrakona -

Farmers' Organizations in Bangladesh: a Mapping and Capacity

Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: Investment Centre Division A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Viale delle Terme di Caracalla – 00153 Rome, Italy. Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component FAO Representation in Bangladesh House # 37, Road # 8, Dhanmondi Residential Area Dhaka- 1205. iappta.fao.org I3593E/1/01.14 Farmers’ Organizations in Bangladesh: A Mapping and Capacity Assessment Bangladesh Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project Technical Assistance Component Food and agriculture organization oF the united nations rome 2014 Photo credits: cover: © CIMMYt / s. Mojumder. inside: pg. 1: © FAO/Munir uz zaman; pg. 4: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 6: © FAO / F. Williamson-noble; pg. 8: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 18: © FAO / i. alam; pg. 38: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 41: © FAO / i. nabi Khan; pg. 44: © FAO / g. napolitano; pg. 47: © J.F. lagman; pg. 50: © WorldFish; pg. 52: © FAO / i. nabi Khan. Map credit: the map on pg. xiii has been reproduced with courtesy of the university of texas libraries, the university of texas at austin. the designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and agriculture organization of the united nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. the mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Uposhakha Name

SL Uposhakha Name Reporting Branch District Address Ena ShakurEmarat, Holding No#19/1, 19/3, Panthapath 1 Panthapath Uposhakha Kawran Bazar Dhaka Road, Tejgaon, Dhaka Bishal Center, Tushardhara Zero Point, Tushardhara R/A, 2 Tushardhara Uposhakha Dania Dhaka Matuail, Kadamtoli, Dhaka-1362 18/C Rankin Street, Wari,PS: Wari,Ward#41,DSCC, Dhaka- 3 Wari Uposhakha Stock Exchange Dhaka 1203 267/1-A, Madhya Pirerbag, Mirpur-02 (60 feet road), Dhaka 4 Madhya Pirerbag Uposhakha Darus Salam Road Dhaka Abdullahpur Bus Stand, Union: Teghoria, Thana: South 5 Abdullahpur Uposhakha Aganagar Dhaka Keranigonj, Dhaka 437/4 "Razu Complex", Shimultoli, Joydebpur, Gazipur 6 Shimultoli Uposhakha Gazipur Chowrasta Gazipur Sadar, Gazipur 1/A/1, 2nd colony, Mazar Road, Ward No#10, Mirpur-1, 7 Mazar Road Uposhakha Darus Salam Road Dhaka Dhaka-1216 Hazi M. A. Gafur Square Shopping Mall, Demra Rampura 8 Amulia Staff Quarter Uposhakha Rupganj Dhaka Road, Ward No#69, DSCC, Demra, Dhaka Madani Super Market, Hemayetpur Bus Stand Road, 9 Hemayetpur Uposhakha Gabtoli Bagabari Dhaka Tetuljhora Union, Savar, Dhaka MOMOTA SUPER MARKET, Holding No. 86/2, Block-H, Ward-7, Kaliakoir Pourshava, Chandra Palli Bidyut, Sattar 10 Chandra Uposhakha Chandra Gazipur Road, Thana: Kaliakoir, District: Gazipur Holding No#21/4/A, Zigatola Main road, Ward No# 14, 11 Zigatola Uposhakha Dhanmondi Dhaka DSCC, Dhanmondi, Dhaka-1000 Mohsin Khan Tower, Holding No#98, Ward No# 19, 12 Mouchak Uposhakha Shantinagar Dhaka DSCC, Siddheswari, Dhaka-1217 BhawaniganJ New Market, Bhawaniganj, Baghmara, -

Lamb Annual Report 2020

ANNUAL REPORT | January 2018 - June 2019 Message from the Board Chairperson I am pleased to give my short message to anyone who reads this report of LAMB’s work for 2018/19. It has been a distinct pleasure to have been on the LAMB board for numerous years over the life of my career in Bangladesh of 33 years as an agriculture missionary then scientist. LAMB has evolved over the years, with this past year striking a distinct position. While we as the LAMB Governing Board use the Carver method of governance, this year is the first year where the reporting is using LAMB’s overall goals as the organizing structure (instead of departments). This is a remarkable step in the right direction whereby the fruits of LAMB’s health and development work can be more effectively measured and reported. This past year represents a renewed commitment toward excellence for the future. Everything from improved contacts with local government and health facilities to the NGO Bureau, points LAMB to a brighter future. LAMB responded to flooding in their area by contacts with the UN agencies and became a conduit for relief, proving LAMB’s resilience in not only their forte of health work but also to respond to the needs of the community. A quick perusal of this report will give the reader a real flavour for where LAMB has been in the past year, the results of years of efforts with the local community, and of course wholeness of healing many persons with various illnesses. LAMB is at a cross road; it can remain the same consistent hospital and development team or it can increase its access to finance and investment to become a successful and sustainable hospital, serving both the poor but also the needs of the increasing lower middle income society as Bangladesh people have higher incomes. -

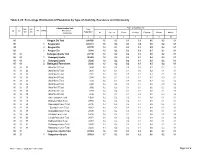

Badarganj Paurashava Table C-09: Percentage Distribution Of

Table C-09: Percentage Distribution of Population by Type of disability, Residence and Community Administrative Unit Type of disability (%) UN / MZ / Total ZL UZ Vill RMO Residence WA MH Population Community All Speech Vision Hearing Physical Mental Autism 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 85 Rangpur Zila Total 2881086 1.6 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 85 1 Rangpur Zila 2438373 1.6 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.6 0.2 0.1 85 2 Rangpur Zila 387370 1.3 0.1 0.3 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 85 3 Rangpur Zila 55343 1.3 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.5 0.2 0.1 85 03 Badarganj Upazila Total 287746 1.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 85 03 1 Badarganj Upazila 262460 1.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.1 85 03 2 Badarganj Upazila 25286 1.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 85 03 2 Badarganj Paurashava 25286 1.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 85 03 01 Ward No-01 Total 3594 1.5 0.5 0.0 0.0 0.7 0.2 0.1 85 03 02 Ward No-02 Total 2891 1.0 0.4 0.1 0.0 0.2 0.1 0.1 85 03 03 Ward No-03 Total 2372 1.1 0.1 0.5 0.1 0.3 0.1 0.0 85 03 04 Ward No-04 Total 2744 1.4 0.1 0.3 0.1 0.5 0.3 0.1 85 03 05 Ward No-05 Total 3134 1.3 0.3 0.3 0.0 0.3 0.2 0.2 85 03 06 Ward No-06 Total 2368 1.4 0.2 0.0 0.1 0.5 0.5 0.2 85 03 07 Ward No-07 Total 3706 1.2 0.0 0.3 0.1 0.6 0.2 0.0 85 03 08 Ward No-08 Total 2259 1.4 0.4 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.1 0.0 85 03 09 Ward No-09 Total 2218 1.2 0.1 0.1 0.2 0.5 0.2 0.2 85 03 16 Kalu Para Union Total 19697 1.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.4 0.1 0.1 85 03 18 Bishnupur Union Total 29860 1.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.1 0.1 85 03 25 Damodarpur Union Total 28310 1.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.5 0.2 0.1 85 03 31 ' Gopalpur' Union Total 28252 1.1 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.4 0.2 0.1 85 03 37 Gopinathpur Union -

Bangladesh: Human Rights Report 2015

BANGLADESH: HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2015 Odhikar Report 1 Contents Odhikar Report .................................................................................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 4 Detailed Report ............................................................................................................................... 12 A. Political Situation ....................................................................................................................... 13 On average, 16 persons were killed in political violence every month .......................................... 13 Examples of political violence ..................................................................................................... 14 B. Elections ..................................................................................................................................... 17 City Corporation Elections 2015 .................................................................................................. 17 By-election in Dohar Upazila ....................................................................................................... 18 Municipality Elections 2015 ........................................................................................................ 18 Pre-election violence .................................................................................................................. -

Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region

Bangladesh Rice J. 21 (2) : 157-172, 2017 Diversity of Cropping Patterns and Land Use Practices in Faridpur Region A B M Mostafizur1*, M A U Zaman1, S M Shahidullah1 and M Nasim1 ABSTRACT The development of agriculture sector largely depends on the reliable and comprehensive statistics of the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of a particular area, which will provide guideline to policy makers, researchers, extensionists and development workers. The study was conducted over all 29 upazilas of Faridpur region during 2015-16 using pre-tested semi-structured questionnaire with a view to document the existing cropping patterns, cropping intensity and crop diversity of this area. From the present study it was observed that about 43.23% net cropped area (NCA) was covered by only jute based cropping patterns on the other hand deep water ecosystem occupied about 36.72% of the regional NCA. The most dominant cropping pattern Boro−Fallow− Fallow occupied about 24.40% of NCA with its distribution over 28 out of 29. The second largest area, 6.94% of NCA, was covered by Boro-B. Aman cropping pattern, which was spread out over 23 upazilas. In total 141 cropping patterns were identified under this investigation. The highest number of cropping patterns was identified 44 in Faridpur sadar and the lowest was 12 in Kashiani of Gopalganj and Pangsa of Rajbari. The lowest crop diversity index (CDI) was reported 0.448 in Kotalipara followed by 0.606 in Tungipara of Gopalganj. The highest value of CDI was observed 0.981 in Faridpur sadar followed by 0.977 in Madhukhali of Faridpur.