Conservation Plan Brockwell Hall and Stables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brockwell Park Walk - SWC

02/05/2020 Brockwell Park walk - SWC Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk Brockwell Park walk Short amble through a small but well-kept urban park in Southeast London on raised ground Length 3.8 km (2.4 mi) or 6.2 km (3.8 mi) Ascent: 70m or 85m Time: 1 hour or 1 1/2 hours walking time. Transport Herne Hill station is located on the boundary between Zones 2 and 3 and served by Southeastern trains on the Chatham Line from Victoria to Orpington, and by Thameslink services on the Portsmouth Line to Sutton. Travel time from Victoria is 9 minutes, from Blackfriars 11 minutes. Brixton station is in Zone 2 and also on the Chatham line, one stop closer to Victoria, and the southern terminus of the Victoria Line Underground. Walk Meandering route through a small but well-kept urban park in Southeast London on raised ground within the valleys Notes shaped by one of London's Hidden Rivers, The Effra, and a couple of its tributaries. Created from the purchase of the existing private gardens of the Brockwell Hall estate and some smaller neighbouring properties, it is noted for its 19th century layout as a gracious public park, a clocktower, water garden, and walled garden, as much as for the Art Deco Brockwell Lido. Brockwell Hall has served as a cafe since the opening of the park in 1892. An Alternative Ending past Brixton Windmill to Brixton Station adds 2.4 km to the route. Eat/Drink Lido Cafe Dulwich Road, Brockwell Park, Herne Hill, SE24 0PA (020 7737 8183). -

Dulwich Road, Herne Hill, SE24 £483 Per Week

Dulwich 94 Lordship Lane London SE22 8HF Tel: 020 8299 6066 [email protected] Dulwich Road, Herne Hill, SE24 £483 per week (£2,100 pcm) 3 bedrooms, 2 Bathrooms Preliminary Details A split level maisonette is ideally located overlooking Brockwell Park. Presented in excellent condition throughout, this property offers a huge reception room, separate kitchen, large bathroom, W/C and three double bedrooms. Many of the rooms have direct views overlooking Brockwell Park for added bonus. On Dulwich Road, the property is close to a host of amenities, including Brockwell Lido. For added bonus, Herne Hill train station, which is in the immediate area, is just 1 stop from Brixton, which offers vastly popular restaurants, bars and clubs. A fantastic property ideal for sharers. Key Features • Three Double Bedrooms • Split Level Maisonette • Opposite Brockwell Park • Close to Amenities • Fantastic Transport Links • Plenty of Light Dulwich | 94 Lordship Lane, London, SE22 8HF | Tel: 020 8299 6066 | [email protected] 1 Area Overview Herne Hill is located in the London Borough of Lambeth and Southwark in Greater London. Herne Hill is situated between the more well known areas of Brixton, Dulwich and Camberwell. It has a range of independent shops, art galleries, bars and restaurants and is home to Brockwell Park. Near the hilltop in Brockwell Park stands Brockwell Hall which was built in 1831. The Park also houses Brockwell Lido and open air swimming pool built in 1937. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2013 Nearest Stations Herne Hill (0.1M) North Dulwich -

Brockwell Park Conservation Area Draft Character Appraisal 2020

Brockwell Park Conservation Area Draft Character Appraisal 2020 INTRODUCTION The Brockwell Park Conservation Area was designated in December 1983 and extended in March 1999. The conservation area is located on the eastern side of Lambeth adjoining the borough boundary with Southwark. It comprises the historic Brockwell Park and development around its perimeter. Only by understanding what gives a conservation area its special architectural or historic interest can we ensure that the character and appearance of the area is preserved or enhanced. This draft character appraisal is prepared by the London Borough of Lambeth to assist with the management of the conservation area. It identifies the features that give the area its special character and appearance. The Council is consulting on this draft version of the appraisal document and the proposals contained within it so that local residents, property owners / building managers and any other interested parties can comment on its content. All comments received will be given careful consideration and where appropriate amendments will be made prior to the adoption of a final version. This draft document is out to consultation from 30 November 2020 to 11 January 2021. Submissions may be made by e-mail: [email protected] In writing to Lambeth Conservation & Urban Design team Phoenix House 10 Wandsworth Road LONDON SW8 2LL All submissions will be considered in detail and amendments made where appropriate. The final version of this document will be made available to view on the Council’s website. Conservation Area Boundary map. 1 Planning Control 1.1 Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 (the Act) requires all local authorities to identify ‘areas of special architectural of historic interest the character and appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’ and designate them as Conservation Areas. -

The Location Specification Welcome to the Linear

WWW.LINEARAPARTMENTS.CO.UK WELCOME TO THE LINEAR APARTMENTS LONDON The latest development by design-led residential developer YellowFish, The Linear Apartments provides an exclusive development of just seven 1, 2 and 3 bedroom apartments providing London living in the heart of Tulse Hill. The Linear Apartments are located at the junction of St Faiths Road with Thurlow Park Road. The development is positioned just a short walk from West Norwood High Street which hosts a monthly farmers market and art fair and West Dulwich Village which provides a range of shops, cafes and restaurants. The development also benefits from local green spaces provided by Brockwell Park, Belair Park and Dulwich Park which provide leisure and recreational facilities together with a full calendar of music, arts and festival events year-round. Tulse Hill Rail Station is located very close to the development which provides easy access into London Bridge, the City and the West End. The Linear Apartments development is comprised of a contemporary four storey building providing three 1 bedroom, two 2 bedroom and two 3 bedroom design-led exceptional quality apartments. Each of the apartments provides modern open-plan style kitchen-living space with direct access to either gardens or balconies, well- proportioned double bedrooms and contemporary family bathrooms. The three largest apartments provide exclusive master bedroom suites with en-suite bathrooms and the three bedroom penthouse boasts a full-length terrace with access from living areas and master suite. The apartments are set within a private-walled courtyard which provides individual secure cycle-store spaces for each of the houses and provides the benefit of both private and communal landscaped front and rear gardens. -

Brockwell Park Accessibility Map Prf6

WC Pu lc olt - a csi l 1 BMX ta k 2 Cidr ic WC Tolt - cide ad aes ny Brxo Brcwl Pak 3 Sprs ltom Unegon Ac esblt Ma WC Pu lc olt - lmtd c es 4 Crce nt Cae 5 Tens ors Brxo Wae Lae Gt Trm Tal 6 Bakt al Tocpit 7 Pig Pn tbe Ply rud Stol A Wae pa Stol B D U Polntr redy ra Bece LW I Bu sos CH Miitr riwy RO Grs & woln P Ca Pak AD SEE GUIDANCE NOTES FOR FURTHER DETAILS ARLINGFORD ROAD Stpe etac t pr ad Ld Brcwl Lio Hen Hil Vei l etac sain Lio P 2 L L I Arigod H E Rod Gt WC S L 7 3 Hen Hil U 1 T WCWC Gae 5 Tus Hil 6 Gae 4 5 5 Comnt Grehue D WC A Brcwl O Pod & R wtad Hal Brcwl Wald D Gae Gadn O O W WC R O N WC Crsiga Loe Gae Roedl Gae L L I H E S L U T Crsiga Upe Gae Nowo Rod Gt Vei l Enrn e BROCKWELL PARK GRDNS RISE Brcwl Pak ITY Gadn Gae TRIN Supported by Brockwell Park Community Partners N Lambeth Council Map designed by Karen BillinghurstMap designed by - [email protected] 1 Brockwell Park accessibility guide - Do you have reduced mobility? - Do you care for a child or young person with a special educational need or disability (SEND)? - Are you disabled or have a special needs of some kind? - Or are you feeling a bit low? Our map of Brockwell Park highlights things to see or do, whether you are disabled, have reduced mobility, care for an adult or child with a SEND or just want to get out to improve your physical health and wellbeing. -

Herne Hill Forum September Events

HERNE HILL FORUM SEPTEMBER EVENTS The Forum held two successful events in September, the purpose being to encourage residents and traders to share their ideas of a vision for the future of Herne Hill. Members of the Society worked on both occasions as part of the Forum. On the 11th there was an open evening HERNE HILL SOCIETY meeting in the Baptist Church Hall in Half EVENTS Moon Lane, attended by around 65 people, including local councillors and Council At Herne Hill United Church Hall, at 7:30 for Officers from both Lambeth and Southwark. 7:45pm, unless otherwise stated. There was an inspirational speech and a ‘walk Wednesday 12 November: round Herne Hill’ on power point from local “Lambeth Mediation Service” by Sonia Reid resident and Chair of the Civic Trust, Philip What is mediation? Kolvin. How and when does it work? How LMS works in the community. Success or failure? Wednesday 10 December: “Music Halls of London” by Chris Sumner, Chair of Waltham Abbey Historical Society Join us in a seasonal treat as we explore the amusements of times past. Wednesday 14 January 2009: “Astronomers and Oddities: The Royal Astronomical Society and its Library” by Peter Hingley The Railton Road Event on 13 September The talk will include local references and items The second event was held in a marquee in the of interest, including some special telescopes. old wood yard in Railton Road on Saturday the Wednesday 11 February: 13th, where several hundred people dropped in “Black Cultural Archives” The history and during the day to chat and exchange ideas. -

Herne Hill Junction

HERNE HILL SOCIETY EVENTS At Herne Hill United Church Hall, at 7:30 for 7:45pm, unless otherwise stated. Sunday 2 September: “Heritage Trail Part 2” Guided walk by Robert Holden. Meet at Herne Hill Station at 2:00pm. Wednesday 12 September: HERNE HILL JUNCTION “My Life in Show Business, Part 2 - The Santa Years” by Robert Holden Detailed analysis and modelling now been completed for a number of alternative designs Wednesday 10 October: for the Junction. These are: the proposals “Murder by Chloroform? The Trial of recommended by the Project Board (Option Adelaide Bartlett” A); moving the slip road four metres further by Robert Flanagan towards the Junction (Option B); moving the slip road twelve metres further towards the Wednesday 14 November: Junction (Option C); and there being no slip “The Story of Bankside” road, but a left turn only lane for vehicles by Len Reilly, Lambeth Archives going from Norwood Road into Dulwich Road Wednesday 12 December: (option D). Silver Anniversary Readings The results of the exercise show that Option D by members of the Society will not improve pedestrian safety and will reduce the capacity of the Junction to handle at present. The level of vehicle saturation will vehicle flows, leading to longer tail-backs than increase to 117%, leading to greater tail-backs than at present, with all the consequent impact on the environment, pedestrian comfort and safety. Option B will result in a smaller pedestrian island, reducing its capacity to handle crowds people at large events and the scope for high quality landscaping. Less effective site-lines will reduce vehicle and pedestrian safety. -

History of Brockwell Park Us About Its Rich History

Did you know? • Brockwell Park is the second largest public open space For more information on Brockwell Park, its restoration in the Borough of and management, please contact Lambeth Council on Lambeth and is 020 7926 9000 or at [email protected]. To find full of fascinating out more about Brockwell Park, including downloading a Brockwell Park history trail buildings and copy of this and other guides, please go to the Lambeth features which tell Council website at www.lambeth.gov.uk Introduction to the history of Brockwell Park us about its rich history. • Brockwell Park itself has existed on this site for over 120 years but records of its past ownership and use go back as far as the 12th Century. Brockwell Park is one of London’s greatest and • Brockwell Park was once part of the ‘Great North most loved public parks, containing not just some Wood’, a dense forest which stretched all the way from fantastic views across the city but also popular the Weald of Sussex and Kent to where Brixton and features including a walled garden, ponds and a Dulwich are today. range of sports and play facilities. The park has recently been restored with funding including from • The land the park lies on was once owned by the Archbishop of Canterbury and then by a monastery the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), The Big Lottery and which founded the famous St. Thomas’ Hospital in the London Borough of Lambeth, in partnership with Waterloo. Brockwell Park Community Partners and a wide range of other stakeholders. -

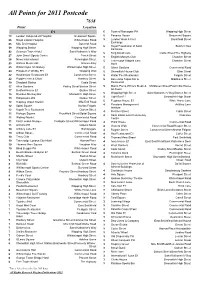

Points Asked How Many Times Today

All Points for 2011 Postcode 7638 Point Location E1 6 Town of Ramsgate PH Wapping High Street 73 London Independent Hospital Beaumont Square 5 Panama House Beaumont Square 66 Royal London Hospital Whitechapel Road 5 London Wool & Fruit Brushfield Street Exchange 65 Mile End Hospital Bancroft Road 5 Royal Foundation of Saint Butcher Row 59 Wapping Station Wapping High Street Katharine 42 Guoman Tower Hotel Saint Katharine’s Way 5 King David Lane Cable Street/The Highway John Orwell Sports Centre Tench Street 27 5 English Martyrs Club Chamber Street News International Pennington Street 26 5 Travelodge Aldgate East Chamber Street 25 Wiltons Music Hall Graces Alley Hotel 25 Whitechapel Art Gallery Whitechapel High Street 5 Albert Gardens Commercial Road 24 Prospect of Whitby PH Wapping Wall 5 Shoreditch House Club Ebor Street 22 Hawksmoor Restaurant E1 Commercial Street 5 Water Poet Restaurant Folgate Street 22 Poppies Fish & Chips Hanbury Street 5 Barcelona Tapas Bar & Middlesex Street 19 Shadwell Station Cable Street Restaurant 17 Allen Gardens Pedley Street/Buxton Street 5 Marco Pierre White's Steak & Middlesex Street/East India House 17 Bedford House E1 Quaker Street Alehouse Wapping High Street Saint Katharine’s Way/Garnet Street 15 Drunken Monkey Bar Shoreditch High Street 5 Light Bar E1 Shoreditch High Street 13 Hollywood Lofts Quaker Street 5 Pegasus House E1 White Horse Lane 12 Stepney Green Station Mile End Road 5 Pensions Management Artillery Lane 12 Spital Square Norton Folgate 4 Institute 12 Kapok Tree Restaurant Osborn Street -

FUSION LIFESTYLE AGREEMENT Relating to the Provision Of

DATED 2006 (1) LONDON BOROUGH OF LAMBETH (2) FUSION LIFESTYLE AGREEMENT relating to the provision of community services at the Brockwell Park Lido REDACTED VERSION: 12 JANUARY 2017 TO BE RELEASED IN RELATION TO INFORMATION REQUEST TO THE LONDON BOROUGH OF LAMBETH: IR175996 FURTHER CIRCULATION STRICTLY PROHIBITED. FUSION LIFESTYLE’S POSITION IS RESERVED IN FULL. 31608/00045/040117121756.docx 31608/00045/040117121756.docx CONTENTS Clause Page 1. Definitions and Interpretation 1 2. Provision of Community Services 4 3. Preparation and Approval of the Community Services Delivery Plan 5 4. Use of the Facility 6 5. Communications Framework 6 6. Staffing 7 7. Fees and Charges 7 8. Commitment to Existing Service Providers 7 9. Performance Measures 8 10. Monitoring and Review 8 11. Accounts and Records 9 12. Insurances 9 13. Termination 9 14. Consequences of Termination 9 15. Dispute Resolution 10 16. No Agency or Partnership 10 17. Assignment and Sub-Contracting 10 18. Announcements 10 19. Confidentiality 10 20. Data Protection Act 1998 11 21. Severability 12 22. Reputation of the Council 12 23. Observance of Statutory Requirements 12 24. Equal Opportunities 12 25. E-Government 12 26. Notices 13 27. Waiver 13 28. Variation 13 29. Force Majeure 13 30. Further Assurance 13 31. Entire Agreement 13 32. Counterparts 14 33. Costs and Expenses 14 34. Rights of Third Parties 14 35. Governing Law and Jurisdiction 14 Schedule 1 - Format and content for Annual Delivery Plan 15 31608/00045/040117121756.docx Schedule 2 - Objectives and Core Outcome 16 Schedule -

Sports & Physical Activities Facilities Strategy for Lambeth Draft Report

London Borough of Lambeth Playing Pitch Assessment 2010-2015 MTW Consultants Limited Leisure and Health Consultants Sports & Physical Activities Facilities Strategy for Lambeth Draft Report Lambeth Council 1 London Borough of Lambeth Playing Pitch Assessment 2010-2015 MTW Consultants Limited Leisure & Health Consultants in association with Around the Block and Cracknell Landscape Architects Prepared for: London Borough of Lambeth Sports and Physical Activities Facilities Strategy for Lambeth DRAFT REPORT: 09.03.10 MTW Consultants Ltd 90-92 Pentonville Road London N1 9HS Tel: 020 3002 4017 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mtwconsultants.co.uk Lambeth Council 2 London Borough of Lambeth Playing Pitch Assessment 2010-2015 CONTENTS PAGE Page No. 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 3. POLICY & STRATEGIC CONTEXT 7 3.1 Overarching Government & Council priorities 7 3.2 National Context 9 3.3 Regional Context 12 3.4 Local Context 14 4 LOCAL BACKGROUND 19 4.1 Strategic geography 19 4.2 Lambeth Demography 20 4.3 Lambeth Sports Participation 23 4.4 Building Schools for the Future 25 4.5 New sports & leisure facilities being developed 27 4.6 Views of county level NGBs 1 30 4.7 Needs of Community organisations 34 4.8 GP Referral and Health Trainers 38 5. PLAYING PITCH ASSESSMENT 42 5.1 Introduction 42 5.2 Team Sports Playing Population 42 5.3 Supply of pitches in Lambeth 43 5.4 Geographic distribution of pitches 48 5.5 Demand for pitches by sport 50 5.6 Local Standards for Playing Pitch Land 69 5.7 Site inspection of playing pitches and ancillary facilities 71 5.8 Synthetic Turf Pitches 78 5.9 Summary of deficiencies and improvements and priorities 80 6. -

Buses from Herne Hill

Buses from Herne Hill 196 3 N3 68 468 N68 towards Elephant & Castle towards Whitehall towards Oxford Circus Walworth Road towards towards Elephant & Castle towards Vauxhall Horse Guards Parade Euston Borough Road Tottenham Court Road from stops A, H196, L, Q 3 fromN3 stops H, J, L, Z 68 468 N68 towards Elephant & Castle towardsfrom stops Whitehall H, J, L, Z towards Oxford Circus Walworth Road towardsfrom stops A, B, H, Q, S, T towardsfrom stops Elephant A, B, H ,& Q Castle, S, T towardsfrom stops A, B, H, Q, S, T Vauxhall Kennington Horse Guards Parade Euston Borough Road Tottenham Court Road from stops A, H, L, Q from stops H, J, L, Z Oval from stops H, J, L, Z from stops A, B, H, Q, S, T from stops A, B, H, Q, S, T from stops A, B, H, Q, S, T Kennington Wandsworth RoadOval 196 KENNINGTON Camberwell Road Wandsworth Road 196 3 N3 Camberwell Green Stockwell KENNINGTONFrom15 June 2019 route 3 will be withdrawn Camberwell Road CAMBERWELL between Whitehall and Trafalgar Square. 3Brixton N3 Road For Trafalgar Square, change at Whitehall to Camberwell Green 37 Stockwell From15 June 2019 route 3 will be withdrawn 68CAMBERWELL 468 N68 Clapham North a northbound bus on another route. N X Brixton between Whitehall and Trafalgar Square. from stops D, , for Clapham Brixton Road For Trafalgar Square, change at Whitehall to 37 High Street Police Station 68 468 N68 Peckham Clapham North a northbound bus on another route. Denmark Hill King’s College Hospital from stopsBus StationD, N, X for Clapham Lambeth BrixtonAtlantic Road HighClapham Street Hospital