Opting out of Spam: a Domain Level Do-Not-Spam Registry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Show Me the Money: Characterizing Spam-Advertised Revenue

Show Me the Money: Characterizing Spam-advertised Revenue Chris Kanich∗ Nicholas Weavery Damon McCoy∗ Tristan Halvorson∗ Christian Kreibichy Kirill Levchenko∗ Vern Paxsonyz Geoffrey M. Voelker∗ Stefan Savage∗ ∗ y Department of Computer Science and Engineering International Computer Science Institute University of California, San Diego Berkeley, CA z Computer Science Division University of California, Berkeley Abstract money at all [6]. This situation has the potential to distort Modern spam is ultimately driven by product sales: policy and investment decisions that are otherwise driven goods purchased by customers online. However, while by intuition rather than evidence. this model is easy to state in the abstract, our under- In this paper we make two contributions to improving standing of the concrete business environment—how this state of affairs using measurement-based methods to many orders, of what kind, from which customers, for estimate: how much—is poor at best. This situation is unsurpris- ing since such sellers typically operate under question- • Order volume. We describe a general technique— able legal footing, with “ground truth” data rarely avail- purchase pair—for estimating the number of orders able to the public. However, absent quantifiable empiri- received (and hence revenue) via on-line store order cal data, “guesstimates” operate unchecked and can dis- numbering. We use this approach to establish rough, tort both policy making and our choice of appropri- but well-founded, monthly order volume estimates ate interventions. In this paper, we describe two infer- for many of the leading “affiliate programs” selling ence techniques for peering inside the business opera- counterfeit pharmaceuticals and software. tions of spam-advertised enterprises: purchase pair and • Purchasing behavior. -

Zambia and Spam

ZAMNET COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS LTD (ZAMBIA) Spam – The Zambian Experience Submission to ITU WSIS Thematic meeting on countering Spam By: Annabel S Kangombe – Maseko June 2004 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 What is spam? 1 1.2 The nature of Spam 1 1.3 Statistics 2 2.0 Technical view 4 2.1 Main Sources of Spam 4 2.1.1 Harvesting 4 2.1.2 Dictionary Attacks 4 2.1.3 Open Relays 4 2.1.4 Email databases 4 2.1.5 Inadequacies in the SMTP protocol 4 2.2 Effects of Spam 5 2.3 The fight against spam 5 2.3.1 Blacklists 6 2.3.2 White lists 6 2.3.3 Dial‐up Lists (DUL) 6 2.3.4 Spam filtering programs 6 2.4 Challenges of fighting spam 7 3.0 Legal Framework 9 3.1 Laws against spam in Zambia 9 3.2 International Regulations or Laws 9 3.2.1 US State Laws 9 3.2.2 The USA’s CAN‐SPAM Act 10 4.0 The Way forward 11 4.1 A global effort 11 4.2 Collaboration between ISPs 11 4.3 Strengthening Anti‐spam regulation 11 4.4 User education 11 4.5 Source authentication 12 4.6 Rewriting the Internet Mail Exchange protocol 12 1.0 Introduction I get to the office in the morning, walk to my desk and switch on the computer. One of the first things I do after checking the status of the network devices is to check my email. -

Email Phishing for IT Providers How Phishing Emails Have Changed and How to Protect Your IT Clients

Email Phishing for IT Providers How phishing emails have changed and how to protect your IT clients 1 © 2016 Calyptix Security Corporation. All rights reserved. I [email protected] I (800) 650 – 8930 (800) 650-8930 I [email protected] Contents Introduction ............................................................................................ 2 Phishing overview .................................................................................. 3 Trends in phishing emails ...................................................................... 6 Email phishing tactics .......................................................................... 11 Steps for MSP & VARS .......................................................................... 24 Advice for your clients .......................................................................... 29 Sources .................................................................................................. 35 1 © 2016 Calyptix Security Corporation. All rights reserved. I [email protected] I (800) 650 – 8930 Introduction There are only so many ways to break into a bank. You can march through the door. You can climb through a window. You can tunnel through the floor. There is the service entrance, the employee entrance, and access on the roof. Criminals who want to rob a bank will probably use an open route – such as a side door. It’s easier than breaking down a wall. Criminals who want to break into your network face a similar challenge. They need to enter. They can look for a weakness in your -

For Immediate Release Crm Monday, November 23, 2009 (202) 514-2007 Tdd (202) 514-1888

___________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CRM MONDAY, NOVEMBER 23, 2009 (202) 514-2007 WWW.JUSTICE.GOV TDD (202) 514-1888 DETROIT SPAMMER AND THREE CO-CONSPIRATORS SENTENCED FOR MULTI-MILLION DOLLAR E-MAIL STOCK FRAUD SCHEME WASHINGTON – Four individuals were sentenced today by U.S. District Judge Marianne O. Battani in federal court in Detroit for their roles in a wide-ranging international stock fraud scheme involving the illegal use of bulk commercial e-mails, or “spamming,” announced Assistant Attorney General of the Criminal Division Lanny A. Breuer and U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan Terrence Berg. Alan M. Ralsky, 64, of West Bloomfield, Mich., and Scott Bradley, 48, also of West Bloomfield, were sentenced to 51 months and 40 months in prison, respectively, for conspiring to commit wire fraud, mail fraud, and to violate the CAN-SPAM Act, and also for committing wire fraud, engaging in money laundering and violating the CAN-SPAM Act. Ralsky and Bradley were also each sentenced to five years of supervised release following their respective prison terms, and were each ordered to forfeit $250,000 that the United States seized in December 2007. How Wai John Hui, 51, a resident of Hong Kong and Canada, was sentenced to 51 months in prison for conspiring to commit wire fraud, mail fraud and to violate the CAN-SPAM Act, and also for committing wire fraud and engaging in money laundering. Hui was sentenced to three years of supervised release following his prison term, and agreed to forfeit $500,000 to the United States. John S. -

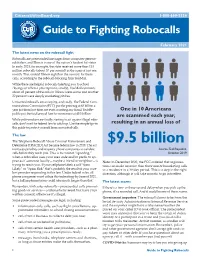

CUB Guide to Fighting Robocalls

CitizensUtilityBoard.org 1-800-669-5556 Guide to Fighting Robocalls February 2021 The latest news on the robocall fi ght Robocalls are prerecorded messages from computer-generat- ed dialers, and Illinois is one of the nation’s hardest hit states. In early 2021, for example, the state received more than 153 million robocalls (about 57 per second) in the span of just one month. That ranked Illinois eighth in the country for these calls, according to the robocall-blocking fi rm YouMail. While there are helpful robocalls (alerting you to school closings or when a prescription is ready), YouMail estimates about 42 percent of the calls in Illinois were scams and another 22 percent were simply marketing pitches. Unwanted robocalls are annoying, and costly. The Federal Com- munications Commission (FCC) put the price tag at $3 billion a year just from lost time, not even counting any fraud. TechRe- One in 10 Americans public put the total annual loss for consumers at $9.5 billion. are scammed each year, While policymakers are fi nally starting to act against illegal robo- calls, don’t wait for federal law to catch up. Use the simple tips in resulting in an annual loss of this guide to protect yourself from unwanted calls. The law The Telephone Robocall Abuse Criminal Enforcement and $9.5 billion Deterrence (TRACED) Act became federal law in 2019. The act increases penalties and requires phone companies to validate Source: TechRepublic, calls before they reach you. This is to combat “spoofi ng,” October 2019 when a robocaller uses your area code and/or prefi x to ap- pear as if someone locally—maybe a friend or neighbor—is Note: In December 2020, the FCC ordered that organiza- trying to reach you. -

Locating Spambots on the Internet

BOTMAGNIFIER: Locating Spambots on the Internet Gianluca Stringhinix, Thorsten Holzz, Brett Stone-Grossx, Christopher Kruegelx, and Giovanni Vignax xUniversity of California, Santa Barbara z Ruhr-University Bochum fgianluca,bstone,chris,[email protected] [email protected] Abstract the world-wide email traffic [20], and a lucrative busi- Unsolicited bulk email (spam) is used by cyber- ness has emerged around them [12]. The content of spam criminals to lure users into scams and to spread mal- emails lures users into scams, promises to sell cheap ware infections. Most of these unwanted messages are goods and pharmaceutical products, and spreads mali- sent by spam botnets, which are networks of compro- cious software by distributing links to websites that per- mised machines under the control of a single (malicious) form drive-by download attacks [24]. entity. Often, these botnets are rented out to particular Recent studies indicate that, nowadays, about 85% of groups to carry out spam campaigns, in which similar the overall spam traffic on the Internet is sent with the mail messages are sent to a large group of Internet users help of spamming botnets [20,36]. Botnets are networks in a short amount of time. Tracking the bot-infected hosts of compromised machines under the direction of a sin- that participate in spam campaigns, and attributing these gle entity, the so-called botmaster. While different bot- hosts to spam botnets that are active on the Internet, are nets serve different, nefarious goals, one important pur- challenging but important tasks. In particular, this infor- pose of botnets is the distribution of spam emails. -

Address Munging: the Practice of Disguising, Or Munging, an E-Mail Address to Prevent It Being Automatically Collected and Used

Address Munging: the practice of disguising, or munging, an e-mail address to prevent it being automatically collected and used as a target for people and organizations that send unsolicited bulk e-mail address. Adware: or advertising-supported software is any software package which automatically plays, displays, or downloads advertising material to a computer after the software is installed on it or while the application is being used. Some types of adware are also spyware and can be classified as privacy-invasive software. Adware is software designed to force pre-chosen ads to display on your system. Some adware is designed to be malicious and will pop up ads with such speed and frequency that they seem to be taking over everything, slowing down your system and tying up all of your system resources. When adware is coupled with spyware, it can be a frustrating ride, to say the least. Backdoor: in a computer system (or cryptosystem or algorithm) is a method of bypassing normal authentication, securing remote access to a computer, obtaining access to plaintext, and so on, while attempting to remain undetected. The backdoor may take the form of an installed program (e.g., Back Orifice), or could be a modification to an existing program or hardware device. A back door is a point of entry that circumvents normal security and can be used by a cracker to access a network or computer system. Usually back doors are created by system developers as shortcuts to speed access through security during the development stage and then are overlooked and never properly removed during final implementation. -

February 2008

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Intergovernmental and Public Liaison The Office of Intergovernmental and Public Liaison’s Department of Justice Newsletter Volume 2, Issue 1 February 2008 Attorney General Mukasey Announces $200 Million February Highlights: Initiative Targeted to Fight Violent Crime ♦ AG announces new initiative to Fight Violent Crime (p.1) In a speech before the U.S. Con- ference of Mayors on January 24th, ♦ Celebrating Martin Luther King 2008, Attorney General Michael B. Day (p.2) Mukasey announced the President is seeking $200 million in funding for a ♦ Recent Achievements by the Civil new Violent Crime Reduction Partner- Rights Division (p.2) ship Initiative for Fiscal Year 2009. The funding is part of the Depart- ♦ AG Visit to Mexico (p.3) ment’s strategy to support state and ♦ Criminal Division News (p.3) local law enforcement efforts in com- munities that are experiencing in- ♦ Defense Contractor and Former creases in violent crime and to keep Manager Charged (P.4) crime down in others. ♦ AG Addresses Executive Working “This initiative will help communi- Group (p.4) ties address their specific violent crime challenges, especially where ♦ Preserving Life and Liberty : multiple jurisdictions are involved,” Protect America Act (p.4) Attorney General Mukasey said. “We'll be able to send targeted resources where they are needed the most and where they show the most promise. Through close coordination, Newsletter from the Office of we also can avoid needless duplica- Intergovernmental and Public Liaison tion and free up resources to help U.S. Department of Justice more cities.” Office of Intergovernmental and Public Liaison RFK Main Justice Building, Room 1629 The Violent Crime Reduction Part- 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW nership Initiative will support multi- Washington, D.C. -

The History of Digital Spam

The History of Digital Spam Emilio Ferrara University of Southern California Information Sciences Institute Marina Del Rey, CA [email protected] ACM Reference Format: This broad definition will allow me to track, in an inclusive Emilio Ferrara. 2019. The History of Digital Spam. In Communications of manner, the evolution of digital spam across its most popular appli- the ACM, August 2019, Vol. 62 No. 8, Pages 82-91. ACM, New York, NY, USA, cations, starting from spam emails to modern-days spam. For each 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3299768 highlighted application domain, I will dive deep to understand the nuances of different digital spam strategies, including their intents Spam!: that’s what Lorrie Faith Cranor and Brian LaMacchia ex- and catalysts and, from a technical standpoint, how they are carried claimed in the title of a popular call-to-action article that appeared out and how they can be detected. twenty years ago on Communications of the ACM [10]. And yet, Wikipedia provides an extensive list of domains of application: despite the tremendous efforts of the research community over the last two decades to mitigate this problem, the sense of urgency ``While the most widely recognized form of spam is email spam, the term is applied to similar abuses in other media: instant remains unchanged, as emerging technologies have brought new messaging spam, Usenet newsgroup spam, Web search engine spam, dangerous forms of digital spam under the spotlight. Furthermore, spam in blogs, wiki spam, online classified ads spam, mobile when spam is carried out with the intent to deceive or influence phone messaging spam, Internet forum spam, junk fax at scale, it can alter the very fabric of society and our behavior. -

That Ain't You: Detecting Spearphishing Emails Before They

That Ain't You: Blocking Spearphishing Emails Before They Are Sent Gianluca Stringhinix and Olivier Thonnardz xUniversity College London z Amadeus [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 1 Introduction Companies and organizations are constantly under One of the ways in which attackers try to steal sen- attack by cybercriminals trying to infiltrate corpo- sitive information from corporations is by sending rate networks with the ultimate goal of stealing sen- spearphishing emails. This type of emails typically sitive information from the company. Such an attack appear to be sent by one of the victim's cowork- is often started by sending a spearphishing email. At- ers, but have instead been crafted by an attacker. tackers can breach into a company's network in many A particularly insidious type of spearphishing emails ways, for example by leveraging advanced malware are the ones that do not only claim to come from schemes [21]. After entering the network, attackers a trusted party, but were actually sent from that will perform additional activities aimed at gaining party's legitimate email account that was compro- access to more computers in the network, until they mised in the first place. In this paper, we pro- are able to reach the sensitive information that they pose a radical change of focus in the techniques used are looking for. This process is called lateral move- for detecting such malicious emails: instead of look- ment. Attackers typically infiltrate a corporate net- ing for particular features that are indicative of at- work, gain access to internal machines within a com- tack emails, we look for possible indicators of im- pany and acquire sensitive information by sending personation of the legitimate owners. -

Busting Blocks: Revisiting 47 U.S.C. §230 to Address the Lack of Effective Legal Recourse for Wrongful Inclusion in Spam Filters

Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2011 Busting Blocks: Revisiting 47 U.S.C. §230 to Address the Lack of Effective Legal Recourse for Wrongful Inclusion in Spam Filters Jonathan I. Ezor Touro Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/scholarlyworks Part of the Commercial Law Commons, Communications Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan I. Ezor, Busting Blocks: Revisiting 47 U.S.C. § 230 to Address the Lack of Effective Legal Recourse for Wrongful Inclusion in Spam Filters, XVII Rich. J.L. & Tech. 7 (2011), http://jolt.richmond.edu/ v17i2/article7.pdf. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Richmond Journal of Law and Technology Vol. XVII, Issue 2 BUSTING BLOCKS: REVISITING 47 U.S.C. § 230 TO ADDRESS THE LACK OF EFFECTIVE LEGAL RECOURSE FOR WRONGFUL INCLUSION IN SPAM FILTERS By Jonathan I. Ezor∗ Cite as: Jonathan I. Ezor, Busting Blocks: Revisiting 47 U.S.C. § 230 to Address the Lack of Effective Legal Recourse for Wrongful Inclusion in Spam Filters, XVII Rich. J.L. & Tech. 7 (2011), http://jolt.richmond.edu/v17i2/article7.pdf. I. INTRODUCTION: E-MAIL, BLOCK LISTS, AND THE LAW [1] Consider a company that uses e-mail to conduct a majority of its business, including customer and vendor communication, marketing, and filing official documents. -

Discussion Paper Countering Spam: How to Craft an Effective Anti-Spam

DISCUSSION PAPER COUNTERING SPAM: HOW TO CRAFT AN EFFECTIVE ANTI-SPAM LAW International Telecommunication Union This paper has been prepared for the ITU World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) thematic workshop on Countering Spam, organized under the ITU New Initiatives Programme by the Strategy and Policy Unit (SPU). The paper was written by Matthew B. Prince, CEO and co-founder of Unspam, LLC, a Chicago-based business and government consulting company helping to draft and enforce effective anti-spam laws. He is a member of the Illinois Bar and an Adjunct Professor at the John Marshall Law School. He received his J.D. from the University of Chicago Law School and his B.A. from Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut. For more information visit: http://www.unspam.com/. The meeting project is managed by Robert Shaw ([email protected]) and Claudia Sarrocco ([email protected]) of the Strategy and Policy Unit (SPU) and the series is organized under the overall responsibility of Tim Kelly, Head, SPU. This and the other papers in the series are edited by Joanna Goodrick. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of ITU or its membership. 1 Introduction Since the first anti-spam law worldwide was passed in 1997, at least 75 governments around the world have passed anti-spam laws.1 That first anti-spam law was in fact passed at state-level in the United States, by the state of Nevada.2 The anti-spam laws in existence today take the form of so-called “opt-in” or “opt-out” regulations.