The Cast of the News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Faces $500,000 Budget Deficit

A Student UTER Publication Linn-Benlon Community College, Albany, ~on VOLUME 21 • NUMBER 7 Wednesday, Nov. 15, 1989 Winter term registration cards ready By Bev Thomas Of The Commuter Fully-admitted students who are cur- rently attending LHCC have first grab at classes during early registration for winter term providing they pick up an appoint- ment card, said LHCC Registar Sue Cripe. Appointment cards will be available at the registration counter Nov. 20 through Dec. 4. Registration counter hours are 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday. Appointment registration days are as follows: students with last names H through 0, Tuesday, Dec. 5; last names P through Z, Wednesday, Dec. 6; last names A through G, Thursday, Dec. 7. Students who miss appointments, lose appointment cards or don't pick cards up may-still register early on Dec. 8, Dec. II or they may attend open registration beginning Dec. 12. Returning Evening Degree Program students may register from 7 to 8 p.m. On The COmmuler! JESS REF!; Dec. I, during open registration or by ap- pointment as a continuing fully-admitted Saluting Women Veterans student. Nursing student Carolyn Camden and Student Council Moderator Brian McMullen ride the ASLBCC float in Satur- Part-time student registration begins day's annual Albany Veterans Day Parade. Although the float was beaten out by one constructed by Calapooia Dec. 12 and Community Education Middle School for best in the parade, ASLBCC's entry did win recognition in its category. The LB float is an an. registration for credit and non-credit nual project constructed with the assistance of several campus clubs. -

Congressional Record—House H12183

September 30, 1996 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE H12183 Mr. DE LA GARZA. I yield to the gen- try's service following his reserve mili- SAM JOHNSON of Dallas, standing tleman from New Mexico. tary service. right here, Mr. Speaker, said some in- Mr. RICHARDSON. Mr. Speaker, let Mr. Speaker, I thought that the U.S. credible words to me: I never did give me just say that selflessly the gen- Senate might move more swiftly on them what they wanted. tleman from Texas has talked about Friday last and that we might adjourn Then he said, you know, because this somebody else when in effect this may sine die on Friday, the 27th of Septem- is typical of his humility, all human be the last speech that truly one of the ber. Then there would have been no beings are different. He slapped me on giants in the Congress, the gentleman special orders. We would have gone out the back of my hand. He said, some from Texas, will be giving. sine die. My high school Latin tells me people you do that to them and they Mr. Speaker, I will ask unanimous that means done, no further legislative caved. We actually had two officers consent that the gentleman's speech to action, House and Senate are gone, tra- who were full traitors who collaborated the Congressional Hispanic Caucus be ditional call from the White House to with the enemy their entire captivity part of the RECORD of this proceeding, the leader of the Senate, Mr. TRENT without ever having been tortured. -

Montana Poll Charts Presidential Preferences

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 11-3-1995 Montana poll charts presidential preferences University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "Montana poll charts presidential preferences" (1995). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 13897. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/13897 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Montana University Communications NEWS RELEASE Missoula; MT 59812 (406) 243-2522 This release is available electronically on INN (News Net). Nov. 3, 1995 MONTANA POLL CHARTS PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCES MISSOULA ~ Senator Bob Dole is an early favorite with Montana Republicans, but many remain undecided. And many Montanans like the idea of a major independent or third party candidate in the 1996 presidential race, according to the latest Montana Poll. For this edition of the Montana Poll, 411 adult Montanans were polled statewide September 21-26. The poll is conducted by The University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research. Choosing from a crowded field of 11 Republican presidential candidates at the time of the poll, Montanans overall endorsed Bob Dole most often (28 percent), with 34 percent undecided, said Susan Selig Wallwork, director of the Montana Poll. -

House of Representatives 1437 1996 T82.18

1996 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES T82.18 Nussle Sanford Thomas So the motion to lay the resolution on D-day, the night before. It was Packard Saxton Thornberry Parker Scarborough Tiahrt on the table was agreed to. about my 200th speech. The gentleman Paxon Schaefer Torkildsen A motion to reconsider the vote from Wisconsin [Mr. GUNDERSON] has Peterson (MN) Schiff Traficant whereby said motion was agreed to made about seven, eight speeches in 16 Petri Seastrand Upton was, by unanimous consent, laid on the years. I am about to break 200 tonight, Pombo Sensenbrenner Vucanovich Porter Shadegg Walker table. I think, warning about the spread of Pryce Shaw Walsh T the world's greatest health problem, at Quillen Shays Wamp 82.18 POINT OF PERSONAL PRIVILEGE least in this country, particularly be- Quinn Shuster Watts (OK) Mr. DORNAN rose to a question of Radanovich Skeen Weldon (FL) cause it involves young men in the Ramstad Smith (MI) Weller personal privilege. prime of their lives. Regula Smith (NJ) White The SPEAKER pro tempore, Mr. ``This is from a young man dying of Riggs Smith (WA) Whitfield LAHOOD, pursuant to clause 1 of rule AIDS. His name is John R. Gail, Jr. He Roberts Solomon Wicker IX, recognized Mr. DORNAN for one Rogers Souder Wolf is from Centerville, OH. It says: hour. Rohrabacher Spence Young (AK) `Mr. Dornan, I caught your speech on Mr. DORNAN made the following Ros-Lehtinen Stearns Young (FL) AIDS yesterday over C±SPAN. I must Roth Stump Zeliff statement: Roukema Talent Zimmer ``Mr. Speaker, I will be showing no commend you. -

The Religious Right and the Carter Administration Author(S): Robert Freedman Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Historical Journal, Vol

The Religious Right and the Carter Administration Author(s): Robert Freedman Reviewed work(s): Source: The Historical Journal, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Mar., 2005), pp. 231-260 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4091685 . Accessed: 05/07/2012 11:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Historical Journal. http://www.jstor.org Press TheHistorical Journal, 48, I (2005), pp. 23I-260 ? 2005 CambridgeUniversity DOI: Io.Io17/Sooi8246Xo4oo4285 Printedin the United Kingdom THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT AND THE CARTER ADMINISTRATION* ROBERT FREEDMAN Trinity Hall, Cambridge the late A B S T R AC T. The 'religiousright' cameto prominence in the US during 1970osby campaigning on 'social issues' and encouragingmany fundamentalist and evangelicalChristians to get involvedin politics. However,the fact that it clashedwith 'born again' PresidentJimmy Carterover tax breaksfor religiousschools believed to be discriminatory,together with its illiberalstances on manyissues, meant that it was characterizedas an extremistmovement. I arguethat this assessmentis oversimplified.First, many racists. Christianschools were not racially discriminatory,and theirdefenders resented being labelledas Secondly,few historianshave recognizedthat the Christiansinvolved in the religiousright were among the most secularizedof their kind. -

The Conservative Caucus, Inc. Supporters Throughout the United

The Conservative Caucus,Inc. National Headquartars ^50 Maple Avenue East, Vienna, Virginia 22180 (703) 393-15: HOWARD PHILLIPS' REMARKS AT THE HAYDEN-FONDA PRESS CONFERENCE, SANTA MONICA, CALIFORNIA, iVlAY 24, 1982. Good morning. My name is Howard Phillips. I am National Director of The Conservative Caucus, which is a non-partisan, grass roots lobbying organization, with roughly 400,000 supporters throughout the United States. We have been involved over the years in a number of issues. For example, in 1977 and 1978, we helped organize the nationwide campaign against ratification of the Carter-Torrijos Panama Canal Surrender Treaty. In 1979 and 1980 we led the nationwide, fifty state campaign against ratification of Salt II. Currently, we are focusing considerable emphasis on a campaign which we call "Defunding the Left." We agree with Thomas Jefferson that it is sinful and tyrannical to compel a man to furnish funds for the propagation of ideas which he disbelieves and abhors. We believe that the principle incorporated in the First Amendment which says that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion and which has been interpreted to mean that religious faiths ought not be subsidized, carries with it the implicit understanding that political faiths, likewise, ought not be subsidized. But, the fact of the matter is that, since the early 1960s, when many programs of the Great Society were instituted, literally billions of dollars in Federal funds have been used to underwrite the activities of organizations which have political axes to grind. In his State of the Union message earlier this year. -

Citizens United Pursuant to the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, As Amended ("FECA")

\*m%t Via Hand Delivery Sss 2? H Lawrence H. Norton, Esquire f S^S^^ General Counsel co .f :^Sr'rn Federal Election Commission TJ nj'.i?coP< 999 E Street, NW ^ g§q5 Washington, DC 20463 ^ > 5 CO ~~ Re: Advisory Opinion Request Dear Mr. Norton: This advisory opinion request is being submitted on behalf of Citizens United pursuant to the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended ("FECA"). In particular, Citizens United desires an advisory opinion on the following three issues: (1) whether paid broadcast advertisements for a book titled The Many Faces of John Kerry. which was authored by the organization's president, David N. Bossie, would qualify as "electioneering communications" if the ads are broadcast during either the 30 day period preceding the Democratic National Convention or the 60 day period preceding the presidential election on November 2,2004; (2) whether the broadcast of a documentary film on John Kerry and John Edwards and/or broadcast advertisements for the film would qualify as "electioneering communications" if the film or ads are broadcast during the 60 day period preceding the presidential election on November 2,2004; and (3) if the film or ads at issue in this advisory opinion request qualify as electioneering communications, whether the film or ads for the film or book fall within FECA's press exemption.1 1 Citizens United is aware that on June 25, 2004 the Commission issued Advisory Opinion 2004- 15, which concluded that broadcast advertising of a documentary the included references to President George W. Bush would qualify as an electioneering communication if the ads are aired during the 60 days preceding the general election or 30 days preceding any primary or preference election for the office sought by the candidate. -

Downsize This! Downsize This!

Moore, Michael − Downsize This! Downsize This! Michael Moore Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint the following photographs: John Abbot Photography: photos of David Hoag, President of LTV, and Ralph Larsen, CEO of Johnson /> Archive Photos: photos of Oklahoma building (Chris Smith), Helmut Werner (Hillery), and Keun Hee Lee (Hankyorch). Michael R. Honeywell: photo of William Stavropoulos, Dow Chemical, CEO (M. H. Photo). Black Star: photos of Dwayne Andreas (John Harrington), Edward Brennan (Rob Nelson), and Hillary Clinton (Dennis Brack). Luther S. Miller: photo of David Levan. SABA: photos of Oklahoma City bombing (Jim Argo/SABA photo); Daniel Tellep (Chris Brown/SABA photo); Jan Timmer (Leimdorfer/ R.E.A./SABA photo); Phil Knight (Mark Peterson/SABA photo); and Bill Rutledge (LaraJ. Regan/SABA photo). UPI/Corbis−Bettman: photo of Art Modell. Impact Visuals: photo of Uzi (Russ Marshall). ISBN 0−517−70739−X To my wife, Kathleen, and my daughter, Natalie two very funny people I love immensely. Contents • The Etiquette of Downsizing • Let's All Hop in a Ryder Truck • Would Pat Buchanan Take a Check from Satan? • "Don't Vote—It Only Encourages Them" • Democrat? Republican? Can You Tell the Difference? • Not on the Mayflower? Then Leave! • Big Welfare Mamas • Let's Dump on Orange County • How to Conduct the Rodney King Commemorative Riot • Pagan Babies • Germany Still Hasn't Paid for Its Sins—and I Intend to Collect • So You Want to Kill the President! • Show Trials I'd Like to See • If Clinton Had Balls . • Steve Forbes Was an Alien • Corporate Crooks Trading Cards • Why Are Union Leaders So F#!@ing Stupid? • Balance the Budget? Balance My Checkbook! • Mike's Penal Systems, Inc. -

Why the People Voted 'No'

Audi!: Hotels owe gov't By Mar-Vic C. Munar The MPLC, the public auditor's agreements; terest of $12,691; Variety News Staff office added, failed to "verify ac • One lessees had only partially • Micro Pacific Development THEOFFICEofthePublicAudi curacy of rental computations pro paid; and Inc, which runs Grand Hotel in tor found that several big hotels , vided by the lessees." •Four lessees did not fulfill a Susupe, $17,457; resort and golf courses on Saipan The report submitted by Public previous underpayment dues and •Saipan Portupia Hotel Corp, had reneged on their lease agree Auditor Leo LaMotte to Secre another lessee was not credited which runs Hyatt Regency in ments with the Division of Public tary Benigno Sablan of the De for the overpayment cited in a Garapan, $15,678; and Lands, costing the government a partment of Public Lands and previous audit report. •Suwaso's Coral Ocean Point, total of$888,793 in rental under Natural Resources, MPLC' s The auditor's office identified $3,372. payments. mother agency, found that: the following establishments that The Kan Pacific Saipan Ltd., Two phases of audit were per •Two establishments did not underpaid MPLC between 1990 which operates the Mariana Re formed by the auditor's office. pay the required rentals to MPLC; and 1994: sort Hotel in Marpi, has not paid a Results showed that the delin •Five lessees paid their rentals •Pacific Micronesia Corp. total of$666,841 in rental obliga- quent establishments underpaid but did not compute their rentals which runs the Daichi Hotel in tions. -

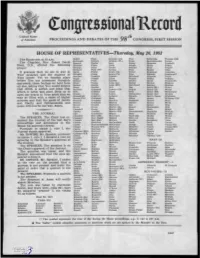

<Tongrtssional Rtcord

<tongrtssional Rtcord United States of Amel'ica PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 98 tb CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, May 26, 1983 The House met at 10 a.m. Bedell Fazio Lehman <CAl Paul Seiberling Thomas<GAl Beilenson Ferraro Lehman <FLl Pease Sensenbrenner Torres The Chaplain, Rev. James David Bennett Fiedler Lent Penny Shannon Torricelli Ford, D.D., offered the following Bereuter Florio Levin Pepper Sharp Towns prayer: Berman Foley Levine Perkins Shaw Traxler Bethune Ford <TNl Levitas Petri Shelby Udall 0 gracious God, we are in awe of Bevill Fowler Lewis <CAl Porter Shumway Valentine Your presence and the majesty of Bilirakis Frank Lewis <FLl Price Sikorski Vandergriff Boehlert Franklin Lipinski Pritchard Siljander Vento Your power. Yet we humbly place Boggs Frenzel Lloyd Pursell Sisisky Volkmer before You our innermost thoughts Boland Frost Loeffler Quillen Skeen Vucanovich and needs, those feelings we hold from Boner Fuqua Long<LAl Rahall Skelton Walgren Booker Garcia Long <MDl Ratchford Slattery Watkins all else, asking that You would forgive Bosco Gaydos Lott Ray Smith <FLl Weber that which is selfish and bless that Boucher Gephardt Lowery <CAl Regula Smith <IAl Wheat which is noble and good. Help us to Britt Gibbons Lujan Reid Smith <NEl Whitehurst open our hearts to Your spirit that we Brooks Gilman Luken Richardson Smith <NJl Whitley Broomfield Gingrich Lungren Rinaldo Smith, Denny Whittaker may be filled with a sense of higher Brown <CAl Glickman Mack Ritter Snowe Williams <OHl purpose and that the goals of justice Broyhill Gonzalez MacKay Robinson Snyder Winn and liberty and righteousness and Bryant Gradison Markey Rodino Spence Wirth Burton Gramm Marlenee Roe Spratt Wise peace will ever be our way. -

OPPOSITION NOTES the American Life League

OPPOSITION NOTES AN INVESTIGATIVE SERIES ON THOSE WHO OPPOSE WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH The American Life League: “More interested in making a statement than making a difference” I INTRODUCTION he American Life League is on the right wing of the antichoice movement, marginalized and isolated even among ostensible allies. Although ALL has made T many ambitious statements of intent since it was founded some 25 years ago, it has failed to deliver on many of its promises and has attracted sharp criticism for apparent financial missteps. So extreme are ALL’s views on abortion and other subjects that it has regularly denounced such reliable conservatives as George W. Bush and Rush Limbaugh for failing to adopt ALL’s own extremism. The league has taken fire from other antichoice groups and—despite oft-professed devotion to the Vatican—from church leaders. In 2004, a spokeswoman for Washington, DC, archbishop Cardinal Theodore McCarrick sought to distance him from an ALL campaign for denial of communion to prochoice politicians. She told the Washington Post McCarrick had been “very clear” that “our teaching” allows Catholics to decide whether to receive communion.1 Douglas Johnson, legislative director of the firmly antichoice National Right to Life Committee, said of ALL in 2003, “I think they’re more The league has taken fire from other antichoice groups interested in making a statement than making a and—despite oft-professed devotion to the Vatican— difference.”2 from church leaders. League president Judie Brown has referred to her supporters, such as they are, as “hardliners”3 who constitute “the real prolife movement.”4 In 1999, the Institute for Democracy Studies said ALL sat atop the “extremist wing of the antichoice movement.”5 “We are laying the groundwork for a Christian movement that will dictate to politicians what it means to be prolife,” Brown once said.6 Despite such grand goals, the league can CATHOLICS FOR A FREE CHOICE OPPOSITION NOTES • AN INVESTIGATIVE SERIES Key Findings point to few effects on politicians’ or can be inflammatory. -

News Clippings from the Dole Archives

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas. ~-3b3- http://dolearchives.ku.edu J ... \.. .( \: . ' ·,,, ., ' . •· j . THE TOpEKA CAPITAL-JOURNAL luniiiiJ, Odatler I; 1111/ N ,. GO~ race:. Still. Dole'. ~ s to lose, . ~.A · · ' a~ update o~ - ¢eir efforts: languish in single di!;ts in'national and ~ng anti-abortion _views. B(lchanan's . ConU~ecl '"":' page · BQB DOLE: Aides believe the New Hampshire polls. Gramm begins a strength with .that constituency_has '' :-', · . · · Idebu~ Perot rushed· into the' s}>otlitiht, . Senate majoritY leader has benefited critical effort to revive his New stymied two cash-strapped longshots: · ' · .' !promising to create a new pol\tical · from _getting a welfare refot:m bill Hampshire effort by launching TV ads California Rep. Bob Dornan and radio · ~ · party imd field a presidential candi- passed; and.are -thrilled with Dole's this week, knowing his support' in the host Alan Keyes. Trying to expand his - Jd!lte ·in 1996. Perot insisted otherwise, cl.ose_ work'ing· r!'!latio~ship with South could wilt if he fails first in the reach to reform-minded Perot voters, but most Republicans· took th·at to Gmgi'lch on budget and other matters. North ...,Absent a Powell or Gingrich Buchanan this week will propose strict ; meim. another Perot candidacy, ·some- Not to ll)entlon 'his big fUQd-~:aising entry, the Dole camp views Gramm as lobbYing and campaign finance refonns. :.Mi~r 1.0. ·days ofparty turmoil; /thing that could seriously diminish leadovertheGOPp~ck. · .. its biggest threat. STEVE FORBES: Since entering the ! GOP odds of winning the White House.