Preliminary Table of Paleozoic Formations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FISHING for DUNKLEOSTEUS You’Re Definitely Gonna Need a Bigger Boat by Mark Peter

OOhhiioo GGeeoollooggyy EEXXTTRRAA July 31, 2019 FISHING FOR DUNKLEOSTEUS You’re definitely gonna need a bigger boat by Mark Peter At an estimated maximum length of 6 to 8.8 meters (20–29 sediments that eroded from the Acadian Mountains, combined feet), Dunkleosteus terrelli (Fig. 1) would have been a match for with abundant organic matter from newly evolved land plants even the Hollywood-sized great white shark from the and marine plankton, settled in the basin as dark organic movie Jaws. Surfers, scuba divers, and swimmers can relax, muds. Over millions of years, accumulation of additional however, because Dunkleosteus has been extinct for nearly 360 overlying sediments compacted the muds into black shale rock. million years. Dunkleosteus was a placoderm, a type of armored The rocks that formed from the Late Devonian seafloor fish, that lived during the Late Devonian Period from about sediments (along with fossils of Dunkleosteus) arrived at their 375–359 million years ago. Fossil remains of the large present location of 41 degrees north latitude after several species Dunkleosteus terrelli are present in the Cleveland hundred million years of slow plate tectonic movement as the Member of the Ohio Shale, which contains rocks that are North American Plate moved northward. approximately 360–359 million years old. Figure 1. A reconstruction of a fully-grown Dunkleosteus terrelli, assuming a length of 29 feet, with angler for scale. Modified from illustration by Hugo Salais of Metazoa Studio. Dunkleosteus cruised Late Devonian seas and oceans as an Figure 2. Paleogeographic reconstruction of eastern North America during apex predator, much like the great white shark of today. -

Message from the New Chairman

Subcommission on Devonian Stratigraphy Newsletter No. 21 April, 2005 MESSAGE FROM THE NEW CHAIRMAN Dear SDS Members: This new Newsletter gives me the pleasant opportunity to thank you for your confidence which should allow me to lead our Devonian Subcommission successfully through the next four years until the next International Geological Congress in Norway. Ahmed El Hassani, as Vice-Chairman, and John Marshall, as our new Secretary, will assist and help me. As it has been our habit in the past, our outgoing chairman, Pierre Bultynck, has continued his duties until the end of the calendar year, and in the name of all the Subcommission, I like to express our warmest thanks to him for all his efforts, his enthusi- asm for our tasks, his patience with the often too slow progress of research, and for the humorous, well organized and skil- ful handling of our affairs, including our annual meetings. At the same time I like to thank all our outgoing Titular Members for their partly long-time service and I express my hope that they will continue their SDS work with the same interest and energy as Corresponding Members. The new ICS rules require a rather constant change of voting members and the change from TM to CM status should not necessarily be taken as an excuse to adopt the lifestyle of a “Devonian pensioner”. I see no reason why constantly active SDS members shouldn´t become TM again, at a later stage. On the other side, the rather strong exchange of voting members should bring in some fresh ideas and some shift towards modern stratigraphical tech- niques. -

Geological Investigations in Ohio

INFORMATION CIRCULAR NO. 21 GEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN OHIO 1956 By Carolyn Farnsworth STATE OF OHIO C. William O'Neill, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES A. W. Marion, Director NATURAL RESOURCES COMMISSION Milton Ronsheim, Chairman John A. Slipher, Bryce Browning, Vice Chairman Secretary C. D. Blubaugh Dean L. L. Rummell Forrest G. Hall Dr. Myron T. Sturgeon A. W. Marion George Wenger DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Ralph J. Bernhagen, Chief STATI OF OHIO DIPAlTMIMT 011 NATUlAL llSOUlCH DIVISION OF &EOLO&ICAL SURVEY INFORMATION CIRCULAR NO. 21 'GEOLOG·ICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN OHIO 1956 by CAROLYN FARNSWORTH COLUMBUS 1957 Blank Page CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Project listing by author 2 Project listing by subject . 22 Economic geology 22 Aggregates . 22 Coal . • 22 Ground water 22 Iron .. 22 Oil and gas 22 Salt . 22 Sand and gravel 23 General .. 23 Geomorphology 23 Geophysics 23 Glacial geology 23 Mineralogy and petrology . 24 Clay .. 24 Coal . 24 Dolomite 24 Limestone. 24 Sandstone •• 24 Shale. 24 Till 25 Others 25 Paleontology. 25 Stratigraphy and sedimentation 26 Structural geology . 27 Miscellaneous . 27 Geographic distribution. 27 Statewide 27 Areal. \\ 28 County 29 Miscellaneous . 33 iii Blank Page I INTRODUCTION In September 1956, letters of inquiry and questionnaires were sent to all Ohio geologists on the mailing list of the Ohio Geological Survey, and to other persons who might be working on geological problems in Ohio. This publication has been compiled from the information contained on the returned forms. In most eases it is assumed that the projects listed herein will culminate in reports which will be available to the profession through scientific journals, government publications, or grad- uate school theses. -

Subsurface Facies Analysis of the Devonian Berea Sandstone in Southeastern Ohio

SUBSURFACE FACIES ANALYSIS OF THE DEVONIAN BEREA SANDSTONE IN SOUTHEASTERN OHIO William T. Garnes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2014 Committee: James Evans, Advisor Jeffrey Snyder Charles Onasch ii ABSTRACT James Evans, Advisor The Devonian Berea Sandstone is an internally complex, heterogeneous unit that appears prominently both in outcrop and subsurface in Ohio. While the unit is clearly deltaic in outcrops in northeastern Ohio, its depositional setting is more problematic in southeastern Ohio where it is only found in the subsurface. The goal of this project was to search for evidence of a barrier island/inlet channel depositional environment for the Berea Sandstone to assess whether the Berea Sandstone was deposited under conditions in southeastern Ohio unique from northeastern Ohio. This project involved looking at cores from 5 wells: 3426 (Athens Co.), 3425 (Meigs Co.), 3253 (Athens Co.), 3252 (Athens Co.), and 3251 (Athens Co.) In cores, the Berea Sandstone ranges from 2 to 10 m (8-32 ft) thick, with an average thickness of 6.3 m (20.7 ft). Core descriptions involved hand specimens, thin section descriptions, and core photography. In addition to these 5 wells, the gamma ray logs from 13 wells were used to interpret the architecture and lithologies of the Berea Sandstone in Athens Co. and Meigs Co. as well as surrounding Vinton, Washington, and Morgan counties. Analysis from this study shows evidence of deltaic lobe progradation, abandonment, and re-working. Evidence of interdistributary bays with shallow sub-tidal environments, as well as large sand bodies, is also present. -

Guide to the Geology of Northeastern Ohio

SDMS US EPA REGION V -1 SOME IMAGES WITHIN THIS DOCUMENT MAY BE ILLEGIBLE DUE TO BAD SOURCE DOCUMENTS. GUIDE TO THE GEOLOGY of NORTHEASTERN OHIO Edited by P. O. BANKS & RODNEY M. FELDMANN 1970 Northern Ohio Geological Society ELYP.i.A PU&UC LIBRARt as, BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF NORTHEASTERN OHIO PENNSYLVANIAN SYSTEM MISSISSIPPIAN SYSTEM DEVONIAN SYSTEM \V&fe'£:i£:VS:#: CANTON viSlSWSSWM FIGURr I Geologic map of northeastern Ohio. Individual formations within each time unit are not dis- -guished, and glacial deposits have been omitted. Because the bedding planes are nearly ••.crizontal, the map patterns of the contacts closely resemble the topographic contours at those z evations. The older and deeper units are most extensively exposed where the major rivers rave cut into them, while the younger units are preserved in the intervening higher areas. CO «< in Dev. Mississippian r-c Penn. a> 3 CO CD BRADF. KINOERHOOK MERAMEC —1 OSAGE CHESTER POTTSVIUE ro to r-» c-> e-> e= e-i GO n « -n V) CO V* o ^_ ^ 0. = -^ eo CO 3 c= « ^> <C3 at ta B> ^ °» eu ra to a O9 eo ^ a* s 1= ca \ *** CO ^ CO to CM v» o' CO to CO 3 =3 13- *•» \ ¥\ A. FIGURE 1. Columnar section ol the major stratigraphic units in northeastern Ohio showing their relative positions in the standard geologic time scale. The Devonian-Mississippian boundary is not known with certainty to lie within the Cleveland Shale. The base of the Mississippian in the northern part of the state is transitional with the Bradford Series of the Devonian System and may lie within the Cleveland Shale (Weller er a/., 1948). -

Middle Devonian Formations in the Subsurface of Northwestern Ohio

STATE OF OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Horace R. Collins, Chief Report of Investigations No. 78 MIDDLE DEVONIAN FORMATIONS IN THE SUBSURFACE OF NORTHWESTERN OHIO by A. Janssens Columbus 1970 SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL STAFF OF THE OHIO DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ADMINISTRATIVE SECTION Horace R. Collins, State Geologist and Di v ision Chief David K. Webb, Jr., Geologist and Assistant Chief Eleanor J. Hyle, Secretary Jean S. Brown, Geologist and Editor Pauline Smyth, Geologist Betty B. Baber, Geologist REGIONAL GEOLOGY SECTION SUBSURFACE GEOLOGY SECTION Richard A. Struble, Geologist and Section Head William J. Buschman, Jr., Geologist and Section Head Richard M. Delong, Geologist Michael J. Clifford, Geologist G. William Kalb, Geochemist Adriaan J anssens, Geologist Douglas L. Kohout, Geologis t Frederick B. Safford, Geologist David A. Stith, Geologist Jam es Wooten, Geologist Aide Joel D. Vormelker, Geologist Aide Barbara J. Adams, Clerk· Typist B. Margalene Crammer, Clerk PUBLICATIONS SECTION LAKE ERIE SECTION Harold J. Fl inc, Cartographer and Section Head Charles E. Herdendorf, Geologist and Sectwn Head James A. Brown, Cartographer Lawrence L. Braidech, Geologist Donald R. Camburn, Cartovapher Walter R. Lemke, Boat Captain Philip J. Celnar, Cartographer David B. Gruet, Geologist Aide Jean J. Miller, Photocopy Composer Jean R. Ludwig, Clerk- Typist STATE OF OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Horace R. Collins, Chief Report of Investigations No. 78 MIDDLE DEVONIAN FORMATIONS IN THE SUBSURFACE OF NORTHWESTERN OHIO by A. Janssens Columbus 1970 GEOLOGY SERVES OHIO CONTENTS Page Introduction . 1 Previous investigations .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Study methods . 4 Detroit River Group . .. .. .. ... .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. 6 Sylvania Sandstone .......................... -

X Hydrogeologic Framework and Geochemistry of Ground Water

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH THE WATER-RESOURCES INVESTIGATIONS REPORT 02-4123 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY, SOUTHERN DIVISION, SHEET 1 of 3 NAVAL FACILITIES ENGINEERING COMMAND Taylor. C.J., and Hostettler, F.D., 2002, Hydrogeologic Framework and Geochemistry of Ground Water and Petroleum in the Silurian-Devonian Carbonate Aquifer, South-Central Louisville, Kentucky science USGSfor a changing world INTRODUCTION (A) (B) (C) (D) Previously published investigations concerning the ground-water resources HOLE DIAMETER, ACOUSTIC HOLE DIAMETER. ACOUSTIC HOLE DIAMETER. ACOUSTIC HOLE DIAMETER, ACOUSTIC of the city of Louisville and Jefferson County, Kentucky, have mostly focused on IN INCHES LITHOLOGY TELEVIEWER IN INCHES LITHOLOGY TELEVIEWER IN INCHES LITHOLOGY TELEVIEWER IN INCHES LITHOLOGY TELEVIEWER the highly productive Ohio River alluvial aquifer (Rorabaugh, 1956; Walker, 1957; Bell. 1966: Unthank and others, 1995). In contrast, relatively little attention has been given to the Ordovician and Silurian-Devonian carbonate aquifers that 10h X 10.4 underlie much of the Louisville and Jefferson County area (fig. I) because of their limited potential for water-supply development (Palmquist and Hall, 1960). LLJ LU O O However, detailed information about the ground-water quality and hydrogeology of £ the carbonate aquifer is needed by State and Federal environmental regulators and o: a: ^ ID private consultants for planning and conducting local environmental t,ite 5% CO C/3 t. * assessments and ground-water remediation. The Silurian-Devonian carbonate Q Q aquifer is of particular interest because it underlies much of the urbanized and 40;: 72%- industrialized areas of the city of Louisville, exhibits moderately well-developed NF karst, and is potentially vulnerable to human-induced contamination. -

Carboniferous Formations and Faunas of Central Montana

Carboniferous Formations and Faunas of Central Montana GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 348 Carboniferous Formations and Faunas of Central Montana By W. H. EASTON GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 348 A study of the stratigraphic and ecologic associa tions and significance offossils from the Big Snowy group of Mississippian and Pennsylvanian rocks UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1962 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U.S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication as follows : Eastern, William Heyden, 1916- Carboniferous formations and faunas of central Montana. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1961. iv, 126 p. illus., diagrs., tables. 29 cm. (U.S. Geological Survey. Professional paper 348) Part of illustrative matter folded in pocket. Bibliography: p. 101-108. 1. Paleontology Montana. 2. Paleontology Carboniferous. 3. Geology, Stratigraphic Carboniferous. I. Title. (Series) For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, B.C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract-__________________________________________ 1 Faunal analysis Continued Introduction _______________________________________ 1 Faunal relations ______________________________ 22 Purposes of the study_ __________________________ 1 Long-ranging elements...__________________ 22 Organization of present work___ __________________ 3 Elements of Mississippian affinity.._________ 22 Acknowledgments--.-------.- ___________________ -

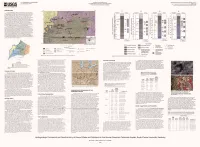

Geologic Cross Section C–C' Through the Appalachian Basin from Erie

Geologic Cross Section C–C’ Through the Appalachian Basin From Erie County, North-Central Ohio, to the Valley and Ridge Province, Bedford County, South-Central Pennsylvania By Robert T. Ryder, Michael H. Trippi, Christopher S. Swezey, Robert D. Crangle, Jr., Rebecca S. Hope, Elisabeth L. Rowan, and Erika E. Lentz Scientific Investigations Map 3172 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Ryder, R.T., Trippi, M.H., Swezey, C.S. Crangle, R.D., Jr., Hope, R.S., Rowan, E.L., and Lentz, E.E., 2012, Geologic cross section C–C’ through the Appalachian basin from Erie County, north-central Ohio, to the Valley and Ridge province, Bedford County, south-central Pennsylvania: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3172, 2 sheets, 70-p. -

Recent Information Maxville Lime.Stone

.·-~ . f GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF OHIO WILBER STOUT, State Geologist Fourth Series Information Circular No. 3 RECENT INFORMATION ON THE MAXVILLE LIME.STONE by RAYMONDE. LAMBORN COLUMBUS 1945 Reprinted 1961 HOOK I\(..• OHIO GEOL. SURVEY. LAKE ERIE SECTION LIBRARY CARD NO. ·7 STATE CF OHIO Michael V. DiSalle Governor DEPARTMENT CF NATURAL RESOURCES Herbert B. Eagon Director NATURAL RESOURCES CCMMISSION C. D. Blubaugh Joseph E. Hunt Herbert B. Eagon Roy M. Kottman Byron Frederick DemClB L. Sean Forrest G. Hl1ll Myron T. Sturgeon Willian• Hoyne DIVISION OF GEQ.OGICAL SURVEY Ralph j. Bernhagen Chief COLUMBUS 1945 Reprinted 1961 Heer ptg. Co., Cols., O. INTRODUCTION The Maxville has been an important source of limestone for more than 100 years in southern and east central Ohio where it was first utilized for mortar and for furnace flux. Probably for this rea~on outcrops of a limestone later shown to be Maxville in age were described by Briggs in 1838 who noted occurrences near Maxville, Perry County; on Three Mile Run near Logan in Hocking County; near Reeds Mills near Wellston, Jackson County; and at the Canter Quarry in Hamilton Township, Jack- son County.1 Further obser.vations of this limestone were made by E. B. Andrews of the Second Geological Survey of Ohio and his report was published in the Report of Progress in 1869. Andrews named the lime- stone the Maxville for its occurrence near Maxville, Hocking County, noted its patchy distribution on the outcrop, described its stratigraphic position as immediately overlying the Logan sandstones ana shales, and declared the limestone to be of sub-Carboniferous (Mississippian) age. -

Late Devonian and Early Mississippian Distal Basin-Margin Sedimentation of Northern Ohio1

Late Devonian and Early Mississippian Distal Basin-Margin Sedimentation of Northern Ohio1 THOMAS L. LEWIS, Department of Geological Sciences, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH 44115 ABSTRACT. Clastic sediments, derived from southeastern, eastern and northeastern sources, prograded west- ward into a shallow basin at the northwestern margin of the Appalachian Basin in Late Devonian and Early Mississippian time. The western and northwestern boundary of the basin was the submerged Cincinnati Arch. The marine clastic wedges provided a northwest paleoslope and a distal, gentle shelf-edge margin that controlled directional emplacement of coarse elastics. Rising sea levels coupled with differences in sedimen- tation rates and localized soft-sediment deformation within the basin help explain some features of the Bedford and Berea Formations. The presence of sand-filled mudcracks and flat-topped symmetrical ripple marks in the Berea Formation attest to very shallow water deposition and local subaerial exposure at the time of emplacement of part of the formation. Absence of thick, channel-form deposits eastward suggests loss of section during emergence. OHIO J. SCI. 88 (1): 23-39, 1988 INTRODUCTION The Bedford Formation (Newberry 1870) is the most The Ohio Shale, Bedford, and Berea Formations of lithologically varied formation of the group. It is com- northern Ohio are clastic units which record prograda- prised of gray and red mudshales, siltstone, and very tional and transgressional events during Late Devonian fine-grained sandstone. The Bedford Formation thins and Early Mississippian time. The sequence of sediments both to the east and west and reaches its maximum is characterized by (1) gray mudshale, clayshale, siltstone, thickness in the Cleveland area. -

IGS 2015B-Maquoketa Group

,QGLDQD*HRORJLFDO6XUYH\ $ERXW8V_,*66WDII_6LWH0DS_6LJQ,Q ,*6:HEVLWHIGS Website Search ,1',$1$ *(2/2*,&$/6859(< +20( *HQHUDO*HRORJ\ (QHUJ\ 0LQHUDO5HVRXUFHV :DWHUDQG(QYLURQPHQW *HRORJLFDO+D]DUGV 0DSVDQG'DWD (GXFDWLRQDO5HVRXUFHV 5HVHDUFK ,QGLDQD*HRORJLF1DPHV,QIRUPDWLRQ6\VWHP'HWDLOV 9LHZ&DUW 7ZHHW *1,6 0$482.(7$*5283 $ERXWWKH,*1,6 $JH 6HDUFKIRUD7HUP 2UGRYLFLDQ 6WUDWLJUDSKLF&KDUW 7\SHGHVLJQDWLRQ 7\SHORFDOLW\7KH0DTXRNHWD6KDOHZDVQDPHGE\:KLWH S IRUH[SRVXUHVRIEOXHDQGEURZQVKDOH 025(,*65(6285&(6 WKDWDJJUHJDWHIW P LQWKLFNQHVVDORQJWKH/LWWOH0DTXRNHWD5LYHULQ'XEXTXH&RXQW\,RZD *UD\DQG6KDYHU 5HODWHG%RRNVWRUH,WHPV +LVWRU\RIXVDJH 6LQFHLWVILUVWXVHWKHWHUPKDVVSUHDGJUDGXDOO\HDVWZDUGLQWKHSURFHVVEHFRPLQJDJURXSWKDWHPEUDFHVVHYHUDO IRUPDWLRQV *UD\DQG6KDYHU ,WLVQRZXVHGWKURXJKRXW,OOLQRLV :LOOPDQDQG%XVFKEDFKS ZDV H[WHQGHGLQWRQRUWKZHVWHUQ,QGLDQDE\*XWVWDGW DQGZDVDGRSWHGIRUXVHLQDJURXSVHQVHWKURXJKRXW,QGLDQD 5(/$7('6,7(6 E\*UD\ *UD\DQG6KDYHU 86*6*(2/(; 'HVFULSWLRQ 1RUWK$PHULFDQ6WUDWLJUDSKLF $VGHVFULEHGE\*UD\ WKH0DTXRNHWD*URXSLQ,QGLDQDLVDZHVWZDUGWKLQQLQJZHGJHIW P WKLFNLQ &RGH VRXWKHDVWHUQ,QGLDQDDQGIW P WKLFNLQQRUWKZHVWHUQ,QGLDQD *UD\DQG6KDYHU ,WFRQVLVWVSULQFLSDOO\RI $$3*&2681$&KDUW VKDOH DERXWSHUFHQW OLPHVWRQHFRQWHQWLVPLQLPDOWKURXJKRXWPRVWRI,QGLDQDEXWLQFUHDVHVSURPLQHQWO\LQWKH VRXWKHDVWVRWKDWSDUWVRIWKHJURXSDUHLQSODFHVGRPLQDQWO\OLPHVWRQH *UD\DQG6KDYHU 7KHORZHUSDUWRIWKH JURXSLVHYHU\ZKHUHDOPRVWHQWLUHO\VKDOHDQGWKHORZHUSDUWRIWKHVKDOHLVGDUNEURZQWRQHDUO\EODFN *UD\DQG 6KDYHU $VDFRQVHTXHQFHRIWKLVSDWWHUQRIURFNGLVWULEXWLRQWZRVFKHPHVRIQRPHQFODWXUHDUHXVHGLQVXEGLYLVLRQRIWKH 0DTXRNHWD*URXSLQ,QGLDQD