Management of Opioid Tolerability and Related Adverse Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biased Versus Partial Agonism in the Search for Safer Opioid Analgesics

molecules Review Biased versus Partial Agonism in the Search for Safer Opioid Analgesics Joaquim Azevedo Neto 1 , Anna Costanzini 2 , Roberto De Giorgio 2 , David G. Lambert 3 , Chiara Ruzza 1,4,* and Girolamo Calò 1 1 Department of Biomedical and Specialty Surgical Sciences, Section of Pharmacology, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] (J.A.N.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 Department of Morphology, Surgery, Experimental Medicine, University of Ferrara, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (R.D.G.) 3 Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Management, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK; [email protected] 4 Technopole of Ferrara, LTTA Laboratory for Advanced Therapies, 44122 Ferrara, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Academic Editor: Helmut Schmidhammer Received: 23 July 2020; Accepted: 23 August 2020; Published: 25 August 2020 Abstract: Opioids such as morphine—acting at the mu opioid receptor—are the mainstay for treatment of moderate to severe pain and have good efficacy in these indications. However, these drugs produce a plethora of unwanted adverse effects including respiratory depression, constipation, immune suppression and with prolonged treatment, tolerance, dependence and abuse liability. Studies in β-arrestin 2 gene knockout (βarr2( / )) animals indicate that morphine analgesia is potentiated − − while side effects are reduced, suggesting that drugs biased away from arrestin may manifest with a reduced-side-effect profile. However, there is controversy in this area with improvement of morphine-induced constipation and reduced respiratory effects in βarr2( / ) mice. Moreover, − − studies performed with mice genetically engineered with G-protein-biased mu receptors suggested increased sensitivity of these animals to both analgesic actions and side effects of opioid drugs. -

Methadone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP) 5 Mg, 10 Mg Rx Only

ROXANE LABORATORIES, INC. Columbus, OH 43216 DOLOPHINE® HYDROCHLORIDE CII (Methadone Hydrochloride Tablets, USP) 5 mg, 10 mg Rx Only Deaths, cardiac and respiratory, have been reported during initiation and conversion of pain patients to methadone treatment from treatment with other opioid agonists. It is critical to understand the pharmacokinetics of methadone when converting patients from other opioids (see DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION). Particular vigilance is necessary during treatment initiation, during conversion from one opioid to another, and during dose titration. Respiratory depression is the chief hazard associated with methadone hydrochloride administration. Methadone's peak respiratory depressant effects typically occur later, and persist longer than its peak analgesic effects, particularly in the early dosing period. These characteristics can contribute to cases of iatrogenic overdose, particularly during treatment initiation and dose titration. In addition, cases of QT interval prolongation and serious arrhythmia (torsades de pointes) have been observed during treatment with methadone. Most cases involve patients being treated for pain with large, multiple daily doses of methadone, although cases have been reported in patients receiving doses commonly used for maintenance treatment of opioid addiction. Methadone treatment for analgesic therapy in patients with acute or chronic pain should only be initiated if the potential analgesic or palliative care benefit of treatment with methadone is considered and outweighs the risks. Conditions For Distribution And Use Of Methadone Products For The Treatment Of Opioid Addiction Code of Federal Regulations, Title 42, Sec 8 Methadone products when used for the treatment of opioid addiction in detoxification or maintenance programs, shall be dispensed only by opioid treatment programs (and agencies, practitioners or institutions by formal agreement with the program sponsor) certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and approved by the designated state authority. -

Information to Users

The direct and modulatory antinociceptive actions of endogenous and exogenous opioid delta agonists Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Vanderah, Todd William. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 00:14:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/187190 INFORMATION TO USERS This ~uscript }las been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete mannscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginnjng at the upper left-hand comer and contimJing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Opioid Analgesics These Are General Guidelines

Adult Opioid Reference Guide June 2012 Opioid Analgesics These are general guidelines. Patient care requires individualization based on patient needs and responses. Lower doses should be used initially, then titrated up to achieve pain relief, especially if the patient has not been taking opioids for the past week (opioid naïve). Patients who have been taking scheduled opioids for at least the previous 5 days may be considered “opioid tolerant”. These patients may require higher doses for analgesia. Drug # Route Starting Dose Onset Peak Duration Metabolism Half Life Comments (Adults > 50 Kg) Buprenorphine Trans- 5 mcg/hr q 7 DAYS 17 hr 60 hr 7 DAYS Liver 26 hr Maximum dose = 20 mcg/hr patch dermal Extensively metabolized by CYP3A4 enzymes – watch for Example: Butrans® drug interactions Transdermal patches are not available at UIHC Codeine PO 30 - 60 mg q 4 hr 30 min 1½ hr 6 hr Liver 2 - 4 hr Oral not recommended first-line therapy. Some patients cannot metabolize codeine to active morphine. Fentanyl IM 5 mcg/Kg q 1 - 2 hr 7 - 8 min 20 - 50 min 1 - 2 hr Liver 1 - 6 hr* Give IV slowly over several minutes to prevent chest wall IV 0.25 - 1 mcg/Kg as Immediate 1 - 5 min 30 - 60 min rigidity SQ needed Refer to the formulary for administration and monitoring. May be used in patients with renal impairment as it has no active metabolites. Accumulates in adipose tissue with continuous infusion. Trans- 25 mcg/hr 12 - 24 hr 24 hr 48 - 72 hr Transdermal should NOT be used to treat acute pain. -

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone WHAT IS HYDROMORPHONE? sedation, and reduced anxiety. It may also cause Hydromorphone belongs to a class of drugs mental clouding, changes in mood, nervousness, called “opioids,” which includes morphine. It and restlessness. It works centrally (in the has an analgesic potency of two to eight times brain) to reduce pain and suppress cough. greater than that of morphine and has a rapid Hydromorphone use is associated with both onset of action. physiological and psychological dependence. WHAT IS ITS ORIGIN? What is its effect on the body? Hydromorphone is legally manufactured and Hydromorphone may cause: distributed in the United States. However, • Constipation, pupillary constriction, urinary retention, users can obtain hydromorphone from nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, dizziness, forged prescriptions, “doctor-shopping,” impaired coordination, loss of appetite, rash, slow or theft from pharmacies, and from friends and rapid heartbeat, and changes in blood pressure acquaintances. What are its overdose effects? What are the street names? Acute overdose of hydromorphone can produce: Common street names include: Severe respiratory depression, drowsiness • D, Dillies, Dust, Footballs, Juice, and Smack progressing to stupor or coma, lack of skeletal muscle tone, cold and clammy skin, constricted What does it look like? pupils, and reduction in blood pressure and heart Hydromorphone comes in: rate • Tablets, capsules, oral solutions, and injectable Severe overdose may result in death due to formulations respiratory depression. How is it abused? Which drugs cause similar effects? Users may abuse hydromorphone tablets by Drugs that have similar effects include: ingesting them. Injectable solutions, as well as • Heroin, morphine, hydrocodone, fentanyl, and tablets that have been crushed and dissolved oxycodone in a solution may be injected as a substitute for heroin. -

Opioid Receptorsreceptors

OPIOIDOPIOID RECEPTORSRECEPTORS defined or “classical” types of opioid receptor µ,dk and . Alistair Corbett, Sandy McKnight and Graeme Genes encoding for these receptors have been cloned.5, Henderson 6,7,8 More recently, cDNA encoding an “orphan” receptor Dr Alistair Corbett is Lecturer in the School of was identified which has a high degree of homology to Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Glasgow the “classical” opioid receptors; on structural grounds Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, this receptor is an opioid receptor and has been named Glasgow G4 0BA, UK. ORL (opioid receptor-like).9 As would be predicted from 1 Dr Sandy McKnight is Associate Director, Parke- their known abilities to couple through pertussis toxin- Davis Neuroscience Research Centre, sensitive G-proteins, all of the cloned opioid receptors Cambridge University Forvie Site, Robinson possess the same general structure of an extracellular Way, Cambridge CB2 2QB, UK. N-terminal region, seven transmembrane domains and Professor Graeme Henderson is Professor of intracellular C-terminal tail structure. There is Pharmacology and Head of Department, pharmacological evidence for subtypes of each Department of Pharmacology, School of Medical receptor and other types of novel, less well- Sciences, University of Bristol, University Walk, characterised opioid receptors,eliz , , , , have also been Bristol BS8 1TD, UK. postulated. Thes -receptor, however, is no longer regarded as an opioid receptor. Introduction Receptor Subtypes Preparations of the opium poppy papaver somniferum m-Receptor subtypes have been used for many hundreds of years to relieve The MOR-1 gene, encoding for one form of them - pain. In 1803, Sertürner isolated a crystalline sample of receptor, shows approximately 50-70% homology to the main constituent alkaloid, morphine, which was later shown to be almost entirely responsible for the the genes encoding for thedk -(DOR-1), -(KOR-1) and orphan (ORL ) receptors. -

Opioid Receptors in Immune and Glial Cells—Implications for Pain Control

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Repository of the Freie Universität Berlin REVIEW published: 04 March 2020 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00300 Opioid Receptors in Immune and Glial Cells—Implications for Pain Control Halina Machelska* and Melih Ö. Celik Department of Experimental Anesthesiology, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany Opioid receptors comprise µ (MOP), δ (DOP), κ (KOP), and nociceptin/orphanin FQ (NOP) receptors. Opioids are agonists of MOP, DOP, and KOP receptors, whereas nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) is an agonist of NOP receptors. Activation of all four opioid receptors in neurons can induce analgesia in animal models, but the most clinically relevant are MOP receptor agonists (e.g., morphine, fentanyl). Opioids can also affect the function of immune cells, and their actions in relation to immunosuppression and infections have been widely discussed. Here, we analyze the expression and the role of opioid receptors in peripheral immune cells and glia in the modulation of pain. All four opioid receptors have been identified at the mRNA and protein levels in Edited by: immune cells (lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages) in humans, rhesus Sabita Roy, monkeys, rats or mice. Activation of leukocyte MOP, DOP, and KOP receptors was University of Miami, United States recently reported to attenuate pain after nerve injury in mice. This involved intracellular Reviewed by: 2+ Lawrence Toll, Ca -regulated release of opioid peptides from immune cells, which subsequently Florida Atlantic University, activated MOP, DOP, and KOP receptors on peripheral neurons. -

Changes in Spinal and Opioid Systems in Mice Deficient in The

The Journal of Neuroscience, November 1, 2002, 22(21):9210–9220 Changes in Spinal ␦ and Opioid Systems in Mice Deficient in the A2A Receptor Gene Alexis Bailey,1 Catherine Ledent,2 Mary Kelly,1 Susanna M. O. Hourani,1 and Ian Kitchen1 1Pharmacology Group, School of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH United Kingdom, and 2Institut de Recherche Interdisciplinaire en Biologie Humaine et Nucle´ aire, Universite´ Libre de Bruxelles, B-1070 Brussels, Belgium A large body of evidence indicates important interactions be- but not in the brains of the knock-out mice. and ORL1 receptor tween the adenosine and opioid systems in regulating pain at both expression were not altered significantly. Moreover, a significant ␦ the spinal and supraspinal level. Mice lacking the A2A receptor reduction in -mediated antinociception and a significant increase gene have been developed successfully, and these animals were in -mediated antinociception were detected in mutant mice, shown to be hypoalgesic. To investigate whether there are any whereas -mediated antinociception was unaffected. Comparison compensatory alterations in opioid systems in mutant animals, we of basal nociceptive latencies showed a significant hypoalgesia in have performed quantitative autoradiographic mapping of , ␦, , knock-out mice when tested at 55°C but not at 52°C. The results and opioid receptor-like (ORL1) opioid receptors in the brains and suggest a functional interaction between the spinal ␦ and opioid spinal cords of wild-type and homozygous A2A receptor knock- and the peripheral adenosine system in the control of pain out mice. In addition, -, ␦-, and Ϫmediated antinociception pathways. using the tail immersion test was tested in wild-type and homozy- ␦ gous A2A receptor knock-out mice. -

1 Impact of Opioid Agonists on Mental Health in Substitution

Impact of opioid agonists on mental health in substitution treatment for opioid use disorder: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials Supplementary Table 1_ Specific search strategy for each database The following general combination of search terms, Boolean operators, and search fields were used where “*” means that any extension of that word would be considered: Title field [opium OR opiate* OR opioid OR heroin OR medication assisted OR substitution treatment OR maintenance treatment OR methadone OR levomethadone OR buprenorphine OR suboxone OR (morphine AND slow) OR diamorphine OR diacetylmorphine OR dihydrocodeine OR hydromorphone OR opium tincture OR tincture of opium OR methadol OR methadyl OR levomethadyl] AND Title/Abstract field [trial* OR random* OR placebo] AND All fields [depress* OR anxiety OR mental] Wherever this exact combination was not possible, a more inclusive version of the search strategy was considered. Database Search Strategy Ovid for EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of (opium or opiate$ or opioid or heroin or medication Controlled Trials August 2018; Embase 1974 to assisted or substitution treatment or maintenance September 07, 2018; MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead treatment or methadone or levomethadone or of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations buprenorphine or suboxone or (morphine and slow) or and Daily 1946 to September 07, 2018 diamorphine or diacetylmorphine or dihydrocodeine or hydromorphone or opium tincture or tincture of opium or methadol or methadyl -

Hydromorphone and Morphine Are Not the Same Drug!

HYDROmorphone and Morphine are not the same drug! HYDROmorphone and morphine are deemed high risk/high alert medications. An Independent Double Check (IDC) must be done to avoid errors when administering all high risk drugs. Please refer to Clinical Practice Standard 1-20-6-3-260. HYDROmorphone and morphine need to knows: HYDROmorphone is 5 times more potent than morphine! (e.g., 1 mg of HYDROmorphone PO is equivalent to 5 mg of morphine PO) When administered via the subcutaneous route, these drugs are twice as strong! Therefore when converting between oral and subcutaneous routes half the dose. (10 mg of oral morphine = 5 mg of subcutaneous morphine) HYDROmorphone and morphine: The name game. Both drugs are used in the management of moderate to severe pain. HYDROmorphone and morphine come in different brand names and formulations. HYDROmorphone = Dilaudid (Injectable), Jurnista (SR), HYDROmorph Contin (SR) Morphine = Morphine Sulphate (Injectable), MS-IR, M.O.S. (Liquid/Tablet/SR), M-Eslon (SR), Statex (Liquid/Tablet/Supp.), Doloral (Liquid), MS Contin (SR), Kadian (SR) (SR=Slow Release CAP) *As per NH, use the generic names (NOT THE BRAND NAME), of these drugs in your documentation. Common side effects: 3 ‘B’s of opioid prescribing: Common: Nausea, Vomiting, Constipation, Sedation, Syncope, Xerostomia (Dry Mouth), If your client is on an opioid: Delirium, Restlessness, Urinary Retention. Do they have a Breakthrough? Less Common: Respiratory Depression, Do they have something for Barfing? Opioid-Induced Neurotoxicity, Myoclonus, Do they have something for their Bowels? Pruritis (itching). Opioid induced neurotoxicity: What does it look like? Opioid induced neurotoxicity is the result of a build up of toxic opioid metabolites in the blood stream. -

NIDA Drug Supply Program Catalog, 25Th Edition

RESEARCH RESOURCES DRUG SUPPLY PROGRAM CATALOG 25TH EDITION MAY 2016 CHEMISTRY AND PHARMACEUTICS BRANCH DIVISION OF THERAPEUTICS AND MEDICAL CONSEQUENCES NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON DRUG ABUSE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES 6001 EXECUTIVE BOULEVARD ROCKVILLE, MARYLAND 20852 160524 On the cover: CPK rendering of nalfurafine. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Introduction ................................................................................................1 B. NIDA Drug Supply Program (DSP) Ordering Guidelines ..........................3 C. Drug Request Checklist .............................................................................8 D. Sample DEA Order Form 222 ....................................................................9 E. Supply & Analysis of Standard Solutions of Δ9-THC ..............................10 F. Alternate Sources for Peptides ...............................................................11 G. Instructions for Analytical Services .........................................................12 H. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of Compounds .............................................13 I. Nicotine Research Cigarettes Drug Supply Program .............................16 J. Ordering Guidelines for Nicotine Research Cigarettes (NRCs)..............18 K. Ordering Guidelines for Marijuana and Marijuana Cigarettes ................21 L. Important Addresses, Telephone & Fax Numbers ..................................24 M. Available Drugs, Compounds, and Dosage Forms ..............................25 -

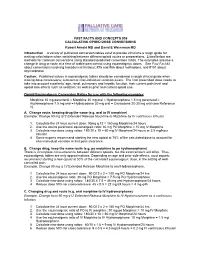

Fast Facts and Concepts

! FAST FACTS AND CONCEPTS #36 CALCULATING OPIOID DOSE CONVERSIONS Robert Arnold MD and David E Weissman MD Introduction A variety of published conversion tables exist to provide clinicians a rough guide for making calculations when switching between different opioid routes or preparations. Listed below are methods for common conversions using standard published conversion ratios. The examples assume a change in drug or route at a time of stable pain control using equianalgesic doses. See Fast Fact #2 about conversions involving transdermal fentanyl; #75 and #86 about methadone; and #181 about oxymorphone. Caution: Published values in equianalgesic tables should be considered a rough clinical guide when making dose conversions; substantial inter-individual variation exists. The final prescribed dose needs to take into account a patients’ age, renal, pulmonary and hepatic function; their current pain level and opioid side effects such as sedation; as well as prior and current opioid use. Opioid Equianalgesic Conversion Ratios for use with the following examples: Morphine 10 mg parenteral = Morphine 30 mg oral = Hydromorphone 1.5 mg parenteral = Hydromorphone 7.5 mg oral = Hydrocodone 30 mg oral = Oxycodone 20-30 mg oral (see Reference 1). A. Change route, keeping drug the same (e.g. oral to IV morphine) Example: Change 90 mg q12 Extended Release Morphine to Morphine by IV continuous infusion 1. Calculate the 24 hour current dose: 90mg q 12 = 180 mg Morphine/24 hours 2. Use the oral to parenteral equianalgesic ratio: 30 mg PO Morphine = 10 mg IV Morphine 3. Calculate new dose using ratios: 180/30 x 10 = 60 mg IV Morphine/24 hours or 2.5 mg/hour infusion 4.