Pig-Prqducjion Methods in Denmark, Sweden, Holland and Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexism in the City “We're Simply Buying Too Much”

SEPTEMBER 2016 Japan’s number one English language magazine Five style-defining brands that are reinventing tradition SEXISM IN THE CITY Will men and women ever be equal in Japan’s workforce? “WE’RE SIMPLY BUYING TOO MUCH” Change the way you shop PLUS: The Plight of the Phantom Pig, Healthy Ice Cream, The Beauties of Akita, Q&A with Paralympics Athlete Saki Takakuwa 36 20 24 30 SEPTEMBER 2016 radar in-depth guide THIS MONTH’S HEAD TURNERS COFFEE-BREAK READS CULTURE ROUNDUP 8 AREA GUIDE: SENDAGAYA 19 SEXISM IN THE CITY 41 THE ART WORLD Where to eat, drink, shop, relax, and climb Will men and women ever be equal This month’s must-see exhibitions, including a miniature Mt. Fuji in Japan’s workforce? a “Dialogue with Trees,” and “a riotous party” at the Hara Museum. 10 STYLE 24 “WE’RE SIMPLY BUYING TOO MUCH” Bridge the gap between summer and fall Rika Sueyoshi explains why it’s essential 43 BOOKS with transitional pieces including one very that we start to change the way we shop See Tokyo through the eyes – and beautiful on-trend wrap skirt illustrations – of a teenager 26 THE PLIGHT OF THE PHANTOM PIG 12 BEAUTY Meet the couple fighting to save Okinawa’s 44 AGENDA We round up the season’s latest nail colors, rare and precious Agu breed Take in some theatrical Japanese dance, eat all featuring a little shimmer for a touch of the hottest food, and enter an “Edo-quarium” glittery glamor 28 GREAT LEAPS We chat with long jumper Saki Takakuwa 46 PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES 14 TRENDS as she prepares for the 2016 Paralympics Hanging out with Cyndi Lauper, Usain Bolt, If you can’t live without ice cream but you’re and other luminaries trying to eat healthier, then you’ll love these 30 COVER FEATURE: YUKATA & KIMONO vegan and fruity options. -

226142258.Pdf

PREDICTING THE PHYSICOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF PORK BELLY AND THE EFFECT OF COOKING AND STORAGE CONDITIONS ON BACON SENSORY AND CHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Food and Bioproduct Sciences University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Olugbenga Philip Soladoye 2017 © Copyright Olugbenga Philip Soladoye, July 2017. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis, or parts thereof, for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Food and Bioproduct Sciences University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N 5A8 i ABSTRACT The first objective of this research was to use a widely varying pig population to create prediction algorithms for dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) pork carcass compositional estimate and pork belly softness measurement. -

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards a PROGRAM for the RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK

Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK This section is organized in the following order: SELECT AN AREA TO VIEW IT Species Cuts Chart LARGER SEE THE Species-Specific FOLLOWING Primal Information AREAS Index of Cuts Cut Nomenclature PORK -- Increasing in and U.P.C.Numbers Popularity Figure 1-- Primal (Wholesale) Cuts and Bone Structure of Pork Figure 2 -- Loin Roasts -- Center Chops INTRODUCTION Figure 3 -- Portion Pieces APPROVED NAMES -- Center Chops BEEF Figure 4-- Whole or Half Loins VEAL PORK Figure 5 -- Center Loin or Strip Loin LAMB GROUND MEATS Pork Belly EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT & Pork Leg FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY Pork Cuts GLOSSARY & REFERENCES Approved by the National Pork Board INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF VEAL PORK LAMB GROUND MEATS EFFECTIVE MEATCASE MANAGEMENT FOOD SAFETY MEAT COOKERY GLOSSARY & REFERENCES INDUSTRY-WIDE COOPERATIVE MEAT IDENTIFICATION STANDARDS COMMITTEE Uniform Retail Meat Identity Standards A PROGRAM FOR THE RETAIL MEAT INDUSTRY APPROVED NAMES PORK INTRODUCTION APPROVED NAMES BEEF -

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (From Either the French Chair Cuite = Cooked Meat, Or the French Cuiseur De

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (from either the French chair cuite = cooked meat, or the French cuiseur de chair = cook of meat) is the branch of cooking devoted to prepared meat products such as sausage primarily from pork. The practice goes back to ancient times and can involve the chemical preservation of meats; it is also a means of using up various meat scraps. Hams, for instance, whether smoked, air-cured, salted, or treated by chemical means, are examples of charcuterie. The French word for a person who prepares charcuterie is charcutier , and that is generally translated into English as "pork butcher." This has led to the mistaken belief that charcuterie can only involve pork. The word refers to the products, particularly (but not limited to) pork specialties such as pâtés, roulades, galantines, crépinettes, etc., which are made and sold in a delicatessen-style shop, also called a charcuterie." SAUSAGE A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted (Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means) meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ A sausage is a food usually made from ground meat , often pork , beef or veal , along with salt, spices and other flavouring and preserving agents filed into a casing traditionally made from intestine , but sometimes synthetic. Sausage making is a traditional food preservation technique. Sausages may be preserved by curing , drying (often in association with fermentation or culturing, which can contribute to preservation), smoking or freezing. -

Profile of Back Bacon Produced from the Common Warthog

foods Article Profile of Back Bacon Produced From the Common Warthog Louwrens C. Hoffman 1,2,* , Monlee Rudman 1,3 and Alison J. Leslie 3 1 Department of Animal Sciences, Faculty AgriSciences, Mike de Vries Building, Private Bag X1, Matieland, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7602, South Africa; [email protected] 2 Centre for Nutrition and Food Sciences, Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation, The University of Queensland, Coopers Plains, QLD 4108, Australia 3 Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology, Faculty AgriSciences, JS Marais Building, Private Bag X1, Matieland, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7602, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: Louwrens.hoff[email protected]; Tel.: +61-4-1798-4547 Received: 7 April 2020; Accepted: 9 May 2020; Published: 15 May 2020 Abstract: The common warthog (Phacochoerus africanus) has historically been hunted and consumed by rural communities throughout its distribution range in Africa. This study aims to develop a processed product from warthog meat in the form of back bacon (Longissimus thoracis et lumborum) as a healthy alternative meat product and to determine its chemical and sensory characteristics derived from adult and juvenile boars and sows. The highest scored attributes included typical bacon and smoky aroma and flavor, and salty flavor, as well as tenderness and juiciness. Neither sex nor age influenced the bacon’s chemical composition; the bacon was high in protein (~29%) and low in total fat (<2%). Palmitic (C16:0), stearic (C18:0), linoleic (C18:2!6), oleic (C18:1!9c), and arachidonic (C20:4!6) were the dominant fatty acids. There was an interaction between sex and age for the PUFA:SFA ratio (p = 0.01). -

Menu for Week

Featured Tsa Tsio (“saat-soo”) (Duroc) $10 per lb. Madagascar's version of Chinese Char Sui pork. Strips of Duroc pork shoulder are cured and marinated overnight in a mix of honey, vanilla-infused rum, our house- made Chinese 5-spice and a little Madagascar-style hot sauce. Enjoy like jerky or slice & use in sandwiches, ramen, salads etc. Pulled Pork (Berkshire) $8 per lb. Whole local Berkshire pork shoulders rubbed with salt and pepper for 2 days. Cold-smoked for 8 hours over a real wood fire of oak and fruitwoods. Then roasted very low and very slow in an oven overnight. Scottish Black Pudding $8 per lb. Traditional blood pudding from Scotland thickened with milk-cooked oats and seasoned with bacon ends, sage and allspice. Ready for a fry up. Smoked Candied Peanuts $4 per đ lb. pack Sweet, crunchy and just a touch of heat. BACONS Brown Sugar Beef Bacon (Piedmontese beef) $9 per lb. (sliced) Grass-fed local Piedmontese beef belly dry- cured for 10 days, coated with black pepper, glazed with brown sugar and smoked over oak and juniper woods. Traditional Bacon (Duroc) $8 per lb. (sliced) No sugar. No nitrites. Nothing but pork belly, salt and smoke. Thick cut traditional dry-cured bacon smoked over a real fire of oak and fruitwoods. Garlic Bacon (Duroc) LIMITED $8 per lb. (sliced) Dry-cured Duroc pork belly coated with garlic and smoked over real wood fire. Black Crowe Bacon (our house bacon) (Duroc) $9 per lb. Dry-cured double-smoked bacon seasoned with black pepper, coffee grounds, garlic and Ancho chili. -

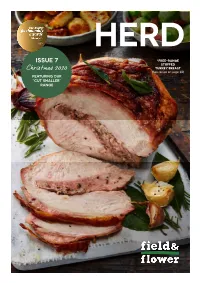

ISSUE 7 Christmas 2020

HERD ISSUE 7 *FREE-RANGE STUFFED TURKEY BREAST Christmas 2020 (See recipe on page 10) FEATURING OUR “CUT SMALLER” RANGE 10 CONTENTS MEET THE TEAM 02 LOCKDOWN ON CASTLEMEAD FARM 04 WELCOME SLOW-GROWN CHRISTMAS BIRDS 08 TURKEY RECIPE 10 It’s very hard to summarise the last 12 months at field&flower. SOUS VIDE 11 As you can imagine, we have a risk document to help us think about the challenges we GRASS-FED CHRISTMAS BEEF 12 might encounter as a small business. You won’t be surprised to hear that a global pandemic wasn’t listed in that document. The biggest risk we’d ever unaccounted for was a few years CHRISTMAS TRIMMINGS 13 ago when a fox helped himself to several hundred turkeys. How times change. CHRISTMAS BREAKFAST 14 The last 6 months have seen the business deal with significant changes and challenges. SALMON RECIPE 16 We have been fortunate enough to keep our doors open so that we can support you, our customers, and we’re proud of the way our team has adapted to deal with a very different BOXING DAY 18 field&flower. The small team we had in March has grown significantly and they have worked OUR PIG FARMER SIMON PRICE 20 day and night to keep our service running smoothly – for which we are exceptionally grateful. FREE-RANGE CHRISTMAS PORK 22 We would like to give a special word of thanks to Liz, our Operations Office Manager. Liz managed the process of keeping everyone safe in our operations base, strategically FARESHARE SOUTHWEST 24 planning shifts and creating work bubbles to ensure the team could continue with their jobs CHRISTMAS SET BOXES & HAMPERS 26 in a safe and efficient way. -

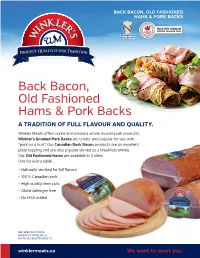

Back Bacon, Old Fashioned Hams & Pork Backs

BACK BACON, OLD FASHIONED HAMS & PORK BACKS Back Bacon, Old Fashioned Hams & Pork Backs A TRADITION OF FULL FLAVOUR AND QUALITY. Winkler Meats offers cured and smoked, whole muscle pork products. Winkler's Smoked Pork Backs are tender and popular for use with “pork on a bun”. Our Canadian Back Bacon products are an excellent pizza topping and are also popular served as a breakfast entrée. Our Old Fashioned Hams are available in 3 sizes. One for every table. • Naturally smoked for full flavour • 100% Canadian pork • High quality, lean cuts • Gluten/allergen free • No MSG added SEE SPECIFICATIONS ON BACK FOR DETAILS ON AVAILABLE PRODUCTS winklermeats.ca We want to meat you. Back Bacon, Old Fashioned Hams & Pork Backs SPECIFICATIONS (*FOOD SERVICES) PRODUCT PRODUCT DISTRIBUTOR ORDER ID CODE DESCRIPTION PKG SIZE PCS/PKG PKG/CASE KGS/CASE CODE IN CASES 1.65kg 3025 Can Back Bacon, Del 1 3 4.95 RDM 5kg Apprx. 3030* Smoked Pork Loin, Sliced 4 20 RDM 50 Slices 5kg 3032* Smoked Pork Loin, Whole 1 4 20 RDM 1.5kg 1303080 Ham, Old Fashioned, Small 1 8 12 RDM Ham, Old Fashioned, 2kg 3080 1 8 16 Medium RDM 4kg 3085 Ham, Old Fashioned, Large 1 4 16 RDM ORDER DETAILS Customer Name .......................................................................................................................................... Customer Address ....................................................................................................................................... Distributor ............................................................... Customer -

Peterson Purveyors LLC 24/7 Order Line 651-756-7145 Product List Jeff

Peterson Purveyors LLC 24/7 Order Line 651-756-7145 Product List Jeff Pierce 612-965-9619 Winter 2019 Chris Peterson 651-261-3831 Lauren Peterson 612-801-7113 Prices and Availability Subject to Change No Minimum and Free Delivery Monday - Friday Product Code Description 0 BEELER'S PORK / ORDER ON THURSDAY, FOR DELIVERY FRIDAY THE FOLLOWING WEEK 00:A:1:A1 Beeler's Pork Whole Bone In Loins 00:A:1:ACCLOIN 66103 Beeler's Pork 11 Rib Center Cut Loin, Chine Bone Off, Tenderloin Out, Blade Bone Removed, Skinless, 2 per case, 20 lb 00:A:1:ACCLOINCHINE 66104 Beeler's Pork 11 Rib Bone In Centercut Loin, Chine Bone On, Tenderloin In, Blade Bone Removed, Skinless, 2 per case, 28 lb 00:A:1:ACCLOINSKIN 66112 Beeler's Pork 11 Rib Bone In Centercut Loin, Chine On, Tenderloin Out, Blade Bone Removed, Skin On, 2 per case, 22 lb 00:A:1:AWLOINBI 66101 Beeler's Pork Whole Bone In Loin, Blade Bone Removed, Skinless, 2 per case, 45 lb 00:A:1:AWLOINBIEA 66199 Beeler's Pork Bone In Loin, Blade Bone Removed, 2 per case, 1 per bag, 45 lb 00:A:1:AWLOINSKIN 66113 Beeler's Pork Whole Bone In Loin, Blade Bone In, Skin On, 2 per case, 52 lb 00:A:1:B1 Beeler's Pork Racks 00:A:1:B9RACK2 56150 Beeler's Pork 9 Rib Rack, Frenched, Chine Off, Skinless, 2 per case, 15 lb 00:A:1:B9RACK4 66310 Beeler's Pork 9 Rib Rack, Frenched, Skinless, 4 per case, 30 lb 00:A:1:B9RACK4EA 66316 Beeler's Pork 9 Rib Rack, Chine Off, Skinless, 4 per case, 1 per bag, 30 lb 00:A:1:B9RACKNF2 66312 Beeler's Pork 9 Rib Rack, Chine Off, Skinless, 2 per case, 15 lb 00:A:1:B9RACKNF4 66116 Beeler's Pork -

Little Cookbooks – Accent – Accent International, Skokie, Illinois

Little Cookbooks – Accent – Accent International, Skokie, Illinois No Date – Good. Accent Cookout Recipes open up a wonderful world of flavor through seasoning. Vertical three-folded black and white sheet. Each panel 5” x 3 3/5”. No Date – Very Good. Accent Flavor Enhancer Serve Half, Freeze Half. Saves your budget …time…and energy! Everyone is looking for ways to serve good-tasting nutritious meals yet stay within the food budget. “Freeze Half. Serve Half” helps you to do just that! Vertical three-folded beige and brown sheet. Each panel 5” x 3”. No Date – Very Good. “Great American Recipes” Magazine insert. Title in red with servings of food and package of Accent in the center. Food in color. Recipes on three panels. Single folded sheet. Each panel 5” x 3”. 11/29/05 Little Cookbooks – Ace Hi – California Milling Corporation, 55th and Alameda, Los Angeles, California 1937 – Fine. Personally Proven Recipes BREAD, BISCUITS, PASTRY. California Milling Corporation, 55th and Alameda, Los Angeles, California. Modern drawing of woman in yellow dress, white apron holding Ace-Hi recipe book. Royal blue background. Back: Ace Hi in bright pink in circle and Family Flour and Packaged Cereals on royal blue background. 4 ¾”x 6 1/8”, no page numbers. 02/13/06 Little Cookbooks – Adcock Pecans – Adcock Pecans, Tifton, Georgia No date – Very Good. Enjoy ADCOCK’S FRESH Papershell Pecans prize-winning Recipes inside . Four folded sheet, blue and white. Brown pecan under title. Each panel, 3 ½”x 8 ½”. 8/21/05 Little Cookbooks – Airline Bee Products – The A. I. Root Company, Medina, Ohio 1915 – Poor. -

Spencer's Jolly Posh British and Irish Foods

EAT FOR BREAKFAST, LUNCH & DINNER! Weird, wonderful and true – bangers and bacon are traditionally eaten at any time of day by the British & Irish. Such is their affection for these tasty little beings, they have invented some truly great recipes, several of which are listed below…. DID YOU KNOW? Bangers and bacon are two of Britain & Ireland’s most genuine and favorite foods, with celebrity fans including Elizabeth Taylor, Michael Caine, Prince Charles, Queen Victoria, and Roger Moore (“007”). British & Irish bacon is traditionally called “back-bacon” because it is made with pork loin. This makes it leaner than American bacon, which is typically from pork belly. British & Irish bangers have a milder, less salty flavor than their American counterparts, and are more finely ground. The addition of a small amount of breadcrumbs softens both the texture and taste. There are over 400 different types of banger sold in Britain & Ireland. They are made from a wide range of fillings, but regardless of the filling a traditional banger is thick, juicy and generous (at least an inch in diameter and 4 to 5 inches long). OUR PRODUCTS Spencer’s product range consists of a delicious dry-cured bacon, and two premium bangers – a Traditional Pork, and a Pork and Herb – which are perfect for tables in pubs, restaurants and homes. Fancy some Bacon? Spencer’s back-bacon is a hand-trimmed, hand-rubbed and dry-cured bacon made to an authentic British recipe. This specialty bacon is made using pork loin, in a dry-cure process that can take up to 10 days – that’s a long time to wait for a decent slice of bacon, but it creates a lean and truly unique flavor. -

Pre-Seventeenth Century Bacon: from Piers Plowman to Sir Kenelm Digby

Pre-seventeenth Century Bacon: from Piers Plowman to Sir Kenelm Digby The Honorable Tomas de Courcy (JdL, GdS) Avacal Arts & Sciences Championship April 7, 2018 1 Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Consumption of Pork in England................................................................................................................... 4 Documenting Bacon ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Bacon Production and Storage ................................................................................................................... 16 Food safety .................................................................................................................................................. 21 Conclusions ................................................................................................................................................. 23 Works Cited ................................................................................................................................................. 25 Abstract This research attempts to fill a gap in historical food scholarship by examining the methods used prior to the seventeenth