PEDESTRIAN SAFETY PROGRAMS - a Review of the January 1981 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School Travel Plan: Safe Routes Hudson

www.saferouteshudson.org SCHOOL TRAVEL PLAN: SAFE ROUTES HUDSON Evamere Elementary School Ellsworth Hill Elementary School McDowell Elementary School East Woods Elementary School Hudson Middle School by Safe Routes Hudson – a community initiated project to promote walking and biking for a healthy Hudson. and TranSystems, Columbus, Ohio Hudson, Ohio December 16, 2011 Table of Contents Section 1 Safe Routes Hudson Team And Target Schools Section 2 Introduction Section 3 Safe Routes Hudson Public Input A. Current Education, Enforcement and Encouragement Programs. B. Past Programs. C. Description of Public Meetings and Outreach. D. Stakeholder Interviews. 1) School Building Principals. 2) City Engineer 3) School Crossing Guards. E. Safe Routes Hudson Survey Summary Results F. Hudson Sidewalk and Connection Plan, 2005 See Attachment B G. Hudson City School District Wellness Policy Section 4 School Demographics Section 5 Current School Travel Environment A. Maps of School Enrollment and Distance to School. B. Student Travel Tallies by School. C. Parent Survey Reports – See Attachment C. D. Student Arrival and Dismissal Procedures. E. School Transportation Policy. F. Crossing Guard Location and Times. G. Sidewalk Maintenance Policy – Ordinance 74-03. Section 6 Barriers to Student Travel – Walking and Biking to School A. Existing Conditions – Community and School District B. Evamere Elementary School C. Ellsworth Hill Elementary School D. McDowell Elementary School E. East Woods Elementary School F. Hudson Middle School G. Field Work/Walk Audit -

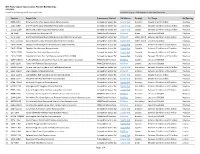

NYC Parks Capital Construction: Planned Bid Openings 5/12/2021 (Sorted by Bid Opening Month and Project Title) Contracts in Gray = Bids Opened Or Removed from Plan

NYC Parks Capital Construction: Planned Bid Openings 5/12/2021 (sorted by bid opening month and project title) contracts in gray = bids opened or removed from plan Contract Project Title Procurement Method Bid Website Borough Est. Range Bid Opening 1 B270-214M Brownsville Park Recreation Center Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Brooklyn Greater than $10 million Apr/May 2 Q163-318M Shore Front Parkway Beach 98th Playground Construction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Queens Between $5 million and $10 million Apr/May 3 Q162E-118M Beach 59th Street Playground Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Queens Between $5 million and $10 million May/Jun 4 XG-321M Bronx Street Tree Planting FY21 MWBE Small Purchase PASSPort Bronx Less than $500,000 May/Jun 5 R172-119M Brookfield Park Operations, Maintenance and Monitoring Services Competitive Sealed Bid PASSPort Staten Island Between $3 million and $5 million May/Jun 6 R117-117MA1 Buono Beach Fountain Reconstruction (Hurricane Sandy) Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Staten Island Less than $1 million May/Jun 7 CNYG-1620M Citywide Electrical Systems Reconstruction (CNYG-1620M) Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Citywide Between $1 million and $3 million May/Jun 8 CNYG-1520M Citywide Pool Electrical Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Citywide Between $1 million and $3 million May/Jun 9 CNYG-1720M Citywide Pool Structural Reconstruction Competitive Sealed Bid Capital Bids Citywide Between $1 million and $3 million May/Jun 10 CNYG-1220M Citywide Synthetic -

To Enter Memo Text

Memorandum DATE January 5, 2018 CITY OF DALLAS TO Honorable Mayor and Members of the City Council SUBJECT Responses to Questions from January 3, 2018 City Council Briefing Item A: Dallas County Schools Dissolution and School Crossing Guard Program On January 3, 2018, Staff presented an overview of the school crossing guard program and the impact of the recent voter dissolution of Dallas County Schools (DCS). Below are responses to questions posed by the City Council during the briefing. 1. Provide an accurate assessment of fees being collected. What is still out there to be captured? As discussed during the briefing, the City currently collects Child Safety Trust Fund fees authorized by state statute to include additional fees added to parking tickets, moving violations in school zones, and truancy violations. To the City’s knowledge, the DCS Dissolution Committee is still collecting the $.01 property tax, and will continue to do so until all their debt obligations are satisfied. Staff continues to work with the DCS Dissolution Committee to get an accurate accounting of fees that are still being collected by DCS. 2. Meet with the Comptroller to get City representatives on DCS Dissolution Committee. Staff scheduled a call with the Comptroller and Mayor Rawlings for Monday, January 8, 2018 at 10:00 am to discuss the City’s representation on the DCS Dissolution Committee. Staff will provide an update to the City Council in the January 9, 2018 Taking Care of Business. 3. What other cities have agreements with DCS? Staff requested from the DCS Dissolution Committee a list of other cities that have current interlocal Agreements (ILAs) for the Stop Arm Camera Program. -

Final Technical Report.Pdf (2.492Mb)

FREEWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY AND EFFICIENCY ENHANCEMENT THROUGH ADAPTIVE ROADWAY LIGHTING AND CONTROL ENABLED BY CONNECTED INFRASTRUCTURE NETWORKS FINAL PROJECT REPORT by Yinhai Wang Haizhong Wang University of Washington Oregon State University Kristian Henrickson Shangjia Dong University of Washington Oregon State University John Ash Hao Yang University of Washington University of Washington Zhibin Li Chen Chen University of Washington Oregon State University Sponsorship US Department of Transportation for Pacific Northwest Transportation Consortium (PacTrans) USDOT University Transportation Center for Federal Region 10 University of Washington More Hall 112, Box 352700 Seattle, WA 98195-2700 In cooperation with US Department of Transportation-Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA) Disclaimer The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. The Pacific Northwest Transportation Consortium, the U.S. Government and matching sponsor assume no liability for the contents or use thereof. i Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Freeway Traffic Safety and Efficiency Enhancement through Adaptive Roadway 12/15/2018 Lighting and Control Enabled by Connected Sensor and Infrastructure Networks 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Yinhai Wang, Haizhong Wang, Kristian Henrickson, Shangjia Dong, John Ash, Hao 2016-M-UW-2 Yang, Zhibin Li, and Chen Chen 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. -

Harlem River Waterfront

Amtrak and Henry Hudson Bridges over the Harlem River, Spuyten Duvyil HARLEM BRONX RIVER WATERFRONT MANHATTAN Linking a River’s Renaissance to its Upland Neighborhoods Brownfied Opportunity Area Pre-Nomination Study prepared for the Bronx Council for Environmental Quality, the New York State Department of State and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation with state funds provided through the Brownfield Opportunity Areas Program. February 2007 Acknowledgements Steering Committee Dart Westphal, Bronx Council for Environmental Quality – Project Chair Colleen Alderson, NYC Department of Parks and Recreation Karen Argenti, Bronx Council for Environmental Quality Justin Bloom, Esq., Brownfield Attorney Paula Luria Caplan, Office of the Bronx Borough President Maria Luisa Cipriano, Partnership for Parks (Bronx) Curtis Cravens, NYS Department of State Jane Jackson, New York Restoration Project Rita Kessler, Bronx Community Board 7 Paul S. Mankiewicz, PhD, New York City Soil & Water Conservation District Walter Matystik, M.E.,J.D., Manhattan College Matt Mason, NYC Department of City Planning David Mojica, Bronx Community Board 4 Xavier Rodriguez, Bronx Community Board 5 Brian Sahd, New York Restoration Project Joseph Sanchez, Partnership for Parks James Sciales, Empire State Rowing Association Basil B. Seggos, Riverkeeper Michael Seliger, PhD, Bronx Community College Jane Sokolow LMNOP, Metro Forest Council Shino Tanikawa, New York City Soil and Water Conservation District Brad Trebach, Bronx Community Board 8 Daniel Walsh, NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Project Sponsor Bronx Council for Environmental Quality Municipal Partner Office of Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrión, Jr. Fiscal Administrator Manhattan College Consultants Hilary Hinds Kitasei, Project Manager Karen Argenti, Community Participation Specialist Justin Bloom, Esq., Brownfield Attorney Paul S. -

115 August 19, 2019 the City Council of Th

RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE GOVERNING BODY CITY OF GARDNER, KANSAS Page No. 2019 – 115 August 19, 2019 The City Council of the City of Gardner, Kansas met in regular session on August 19, 2019, at 7:00 p.m. in the Council Chambers at Gardner City Hall, 120 East Main Street, Gardner, Kansas, with the Mayor Steve Shute presiding. Present were Councilmembers Lee Moore (via telephone), Rich Melton, Mark Baldwin, Randy Gregorcyk, and Todd Winters. City staff present were City Administrator James Pruetting; Business & Economic Development Director Larry Powell; Utilities Director Gonzalo Garcia; Public Works Director Michael Kramer; Parks and Recreation Director Jason Bruce; Finance Director Matthew Wolff; Police Chief James Belcher; City Clerk Sharon Rose; and City Attorney Ryan Denk. Others present included those listed on the attached sign-in sheet and others who did not sign in. CALL TO ORDER There being a quorum of Councilmembers present, the meeting was called to order by Mayor Shute at 7:00 p.m. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Mayor Shute led those present in the Pledge of Allegiance. PRESENTATIONS 1. Proclaim August 31, 2019 as Gardner Day at the K Mayor Shute read a proclamation recognizing August 31, 2019 as Gardner Day at the K in honor of Derek “Bubba” Starling and John Means PUBLIC HEARING PUBLIC COMMENTS Adriana Meder, 32604 W. 171st Ct. - I sent you an email earlier today, but I’d like to read it in to public record. It’s input for NDO (non-discrimination ordinance) for LGBTQ. I request to have an NDO for the LGBTQ community explored, drafted and considered for adoption by the governing body. -

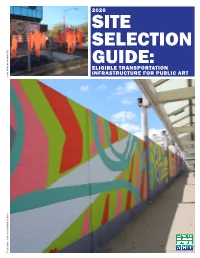

Site Selection Guide

2020 SITE SELECTION GUIDE: ELIGIBLE TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE FOR PUBLIC ART I am Here by Harumi Ori I am Here by Pedestrian Patterns by Mark Salinas Mark by Patterns Pedestrian INTRODUCTION The New York City Department of Transportation’s Art Program (DOT Art) partners with community-based, nonprofit organizations and professional artists to present temporary public artwork on DOT infrastructure throughout the five boroughs. Asphalt, bridges, fences, jersey barriers, medians, plazas, sidewalks, step streets, streetlight poles and triangles serve as canvases and foundations for temporary murals, projections, sculptures and interventions. This guide defines transportation infrastructure eligible for public art installations. Infrastructure is categorized into distinct classifications known as site types. Each definition includes the following supplemental information: ▪ typical elements found at a site; ▪ site requirements and recommendations; and ▪ potential artwork installations associated with each site type. Organizations and artists are invited to select DOT-owned infrastructure within their communities as potential sites for temporary art. Appropriate sites for art are evaluated based on the following criteria: SIZE + SAFETY The site is large enough to accommodate artwork, and the addition of artwork will not impede pedestrian circulation or introduce any public safety hazards. VISIBILITY + ACCESSIBILITY The site is accessible to a diverse audience, in close proximity to public transportation, and adjacent to a mixed used corridor. SITE ENHANCEMENT + SIGNIFICANCE The site is in need of beautification and is historically or geographically relevant to the community. As new priority initiatives arise at the agency as well as policies on a regional and national level, DOT Art may introduce new site typologies eligible for public art. -

Stakeholders Committee Revised General Plan Policy Carryover Subcommittee (Pcs)

STAKEHOLDERS COMMITTEE REVISED GENERAL PLAN POLICY CARRYOVER SUBCOMMITTEE (PCS) Task Purpose The Stakeholders Committee has designated a subcommittee, the Revised General Plan Policy Carryover Subcommittee (PCS), to identify current policies of the Revised General Plan that should be carried forward for inclusion in the New Comprehensive Plan. Obviously, a review of existing policies may prompt ideas of new policies or a revision of current policies; however, the formulation of new and/or revised policies is a separate task to be completed later in the planning process. Task Products A report from the PCS regarding the concurrence of STAC recommendations and any PCS recommendations of carryover policies is the end-product with this part of the task. The report will be a finalized tracking matrix showing the PCS’s recommendation on all policies and a memorandum summarizing the subcommittee’s recommendation. Task Background The current policies are compiled into spreadsheets and categorized by the proposed chapters of the new Comprehensive Plan (Shape, Connect, Compete, Sustain, and Support) as tabs in each worksheet. Only the chapters that had policies corresponding to the topic area (same as the file name) were included in the spreadsheet. The members of the Staff Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) reviewed the policies and provided a recommendation and, if necessary for further clarification, a corresponding comment for the recommendation. Per the consultants’ recommendation to better organize our numerous existing policies, staff has categorized each identified policy as a policy, action, or guideline based on the following understanding of the terms: Policy – A recommended course of action or position on a topic to guide future decisions and/or actions. -

2019 -2022 Suffolk County Local Design Services Agreement Request for Qualifications Package

2019 -2022 SUFFOLK COUNTY LOCAL DESIGN SERVICES AGREEMENT REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS PACKAGE March 29, 2019 Submitted to: Suffolk County Department of Public Works Submitted by: Engineering | Design | Planning | Construction Management With subconsultants: L K McLean Associates B Thayer Associates CSM Engineering, PC EnTech Engineering, PC Gayron deBruin Land Surveying and Engineering, PC Gedeon GRC Consulting M&J Engineering Richard Grubb Associates, Inc. March 29, 2019 Mr. Darnell Tyson, P.E. Acting Commissioner of Public Works County of Suffolk County 335 Yaphank Avenue Yaphank, NY 11980-9744 RE: Expression of Interest for the 2019 – 2022 Suffolk County Local Design Services Agreement Dear Acting Commissioner Tyson: In response to your solicitation, Greenman-Pedersen, Inc. (GPI), along with subconsultants, L K McLean Associates, B. Thayer Associates, CSM Engineering, PC, Gayron deBruin Land Surveying & Engineering, PC, Gedeon GRC Consulting, EnTech Engineering, PC, M&J Engineering and Richard Grubb Associates, Inc. is pleased to submit our team’s expression of interest to be placed on the 2019-2022 Suffolk County Local Design Services Agreement (LDSA) list. The GPI team can readily provide all the services listed—project scoping, preliminary/final design (Design Phases I-VI), community participation, environmental assessment, and subsequent construction support and construction inspection services for municipal highway, bridge, traffic and other related transportation projects. We have a team of outstanding professionals available -

Health & Environment Committee Meeting

HEALTH & ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES – April 5, 2018 COMMITTEE MEMBERS PRESENT: Steve Simon (Chair), Richard Allman, Sara Fisher, Andrea Kornbluth, Elizabeth Lehmann, Beatrice Hall (Public Member). COMMITTEE MEMBERS ABSENT: Daryl Cochrane (Asst. Chair). BOARD MEMBERS PRESENT: Richard Lewis. GUESTS: Tayyaba Alzal, Emmanuel Amoate, Victor Anosike, Sabrina Ariot, Danielle Bonand, Elvis Cruz, Walkiris Cruz- Perez, Abelard Desrosiers, Paul Epstein, Rose Gedeon, Javier Guevolrol, Julia Hakim, Paul Hintersteiner; Leslie-Ann Jerez, Terry-Ann Lawrence, Dew Lizzardi, Ikpechuvwu Obayi, Gillian Perez, Maya Rajapakse, Valinn Ranelli, Dina Rybak, Dawa Sangmo, Al Santino, Phil Simpson, Jeidy Vazquez. S. Simon, chair, called the meeting to order at 7:12 p.m. and introduced the committee members who were present. 1. Presentation by NYC Economic Development Corp. on the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Inwood Rezoning Plan – Dina Rybak, Vice President – Planning, EDC, continued her presentation from last month covering the following topics: Air Quality: Mobile sources (traffic) and stationary sources (heat and hot water building systems) were studied. Intersections chosen as the three worst – 9th Ave. & W. 207th St., Broadway & 219th St. and Major Deegan Expressway and Fordham Rd. in the Bronx – were screened. Conclusion: Rezoning would have no significant adverse impacts on air quality because of traffic and if new development sites use natural gas to fuel boilers, use low-emissions boilers and place stacks at certain locations and heights to allow dispersion. This would be enforced by the Mayor’s Office of Environmental Remediation. Noise: Mobile sources (traffic) did not reach threshold for significant impacts. Stationary sources – they monitored 20 locations in the neighborhood to establish existing levels. -

Fieldston Kingsbridge Spuyten Duyvil Marble Hill Riverdale Van

Neighborhood Map ¯ 240th Street Yard V PS 168 a n Greystone Avenue Manhattan C o 3963 Dash Place College Van Cortlandt Park rt Bx10 l Waldo Avenue Kelly Student Kingsbridge an H uth d e Commons Green So t n rk A Gaelic Park Pa Bx10 ve r t nue W Avenue Orloff Avenue Saxon y Waldo Walk nd H a H tl H r Co Charles Halley Place 101 e e u an Step Street 3850 n V n d 160 r s y y r o 3998 a Avenue Hillman y H n w Avenue Gouverneur u H P 0 St d a 24 re s u W e 180 3958 s r t s k o d w Ethical Culture e 3931 n Bx7 s r e Sheila Mencher a Bx10 P o Fieldston School u y Bx20 p School, PS/MS 95 a n e n E W 240 Street x nu r ve k a e A 3950 E loff w P s v Or t 3898 Van Cortlandt’s 3836 a a Visitation n A y 3900 a r Tail y W k 316 School g 3 e e w e l Fieldston i s 3868 e 3950 3898 t a a 3898 y D W 239 Street B e t r u Manhattan s 3898 182 o n Bell Tower MacLaughlin e j College e a Park Bell Tower Playground W v e 5848 u A n e W 239 St Review Place Sedg ve M wick A f u f Broadway n o l e r v W 238 Street O A Step Street 3800 3800 m 435 a Van Cortlandt Riverdale Avenue n 3800 t 305 3800 u Library P Bx 3660 217 10 5820 Bx 3800 3 181 20 440 Bx 237 3862 501 481 3660 W 238 Street 308 W 238 Street 3800 3800 3800 3660 W 238 Street 275 Cannon Place 69 3800 474 3636 288 Bx3 3646 e Stevenson Place Bx1 u 3850 W 238 Street 492 LTD n 3738 270 3798 e 3816 3798 231 St Fieldston Road vBx1 Greystone Avenue Bx1 ALTD Manhattan Bx2 only W k c i Bx1 R 2 Bx2 3 w 3656 i v 3662 8 g e S r 5800 d d 7 t x r e a B e S le Waldo Avenue e Oxford Avenue t x7 A Irwin Avenue B Street -

Master Thesis

Master Thesis im Rahmen des Universitätslehrganges „Geographical Information Science & Systems“ (UNIGIS MSc) am Zentrum für GeoInformatik (Z_GIS) der Paris Lodron-Universität Salzburg zum Thema AN APPROACH TO GEOCODING BASED ON VOLUNTEERED SPATIAL DATA vorgelegt von Dipl. Wirt.-Inf. (FH) Christof Amelunxen U1336, UNIGIS MSc Jahrgang 2007 Zur Erlangung des Grades “Master of Science (Geographical Information Science & Systems) – MSc (GIS)” Gutachter: Ao. Univ. Prof. Dr. Josef Strobl Paderborn, 19. Juni 2009 Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Alexander Zipf, head of the Re- search Group Cartography, University of Bonn, and Pascal Neis, head developer of OpenRouteService and member of the research group, for giving me the op- portunity to work in this interesting field of research. Their constructive feedback and constant support was of invaluable importance to the success of the work presented with this thesis. Next I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Strobl, head of the Centre for Geomatics (Z_GIS), University of Salzburg, and all members of the UNIGIS team for their support during the time of the masters program of which the completion of this thesis represents the final step. Last but not least I would like to thank my family and friends, who had to tolerate two and a half years of permant shortage of my free time, reaching its climax with the work on this thesis. Statement of Originality I hereby certify that the content of this thesis is the result of my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes, neither in whole nor in part.