U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

Bureau of Justice Statistics

October 2019, NCJ 251922

Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 – Statistical Tables

Connor Brooks, BJS Statistician

s of the end of fscal-year 2016, federal agencies in the United States and

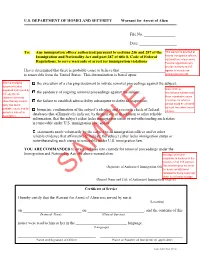

FIGURE 1

Distribution of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by department or branch, 2016

A

U.S. territories employed about 132,000 full-time law enforcement ofcers. Federal law enforcement ofcers were defned as any federal ofcers who were authorized to make arrests and carry frearms. About three-quarters of federal law enforcement ofcers (about 100,000) provided police protection as their primary function. Four in fve federal law enforcement ofcers, regardless of their primary function, worked for either the Department of Homeland Security (47% of all ofcers) or the Department

of Justice (33%) (fgure 1, table 1).

Department of

Homeland Security

Department of Justice

Other executivebranch agencies

Independent agencies

Judicial branch Legislative branch

Findings in this report are from the 2016 Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers (CFLEO). Te Bureau of Justice Statistics conducted the census, collecting data on 83 agencies. Of these agencies, 41 were Ofces of Inspectors General, which provide oversight of federal agencies and activities. Te tables in this report provide statistics on the number, functions, and demographics of federal law enforcement ofcers.

- 0

- 10

- 20

- 30

- 40

- 50

Percent

Note: See table 1 for counts and percentages. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016.

Highlights

In 2016, there were about 100,000 full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in the United States and U.S. territories who primarily provided police protection, compared to 701,000 full-time sworn ofcers in general-purpose state and local law-enforcement agencies nationwide.

Between 2008 and 2016, the Amtrak Police had the largest percentage increase in full-time federal law enforcement ofcers (40%), followed by the National Park Service Rangers (29%) and the Bureau of Indian Afairs (27%).

The Bureau of Indian Afairs experienced the highest rate of assaults on ofcers in 2016 (143 assaults per 100 ofcers), which was more than triple the rate in 2008 (38 per 100) and more than 20 times the rate of any other agency.

About two-thirds of all full-time federal law enforcement ofcers worked for either Customs and Border Protection (33%), the Federal Bureau of Prisons (14%), the FBI (10%), or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (9%).

List of tables

TabLE 1. Distribution of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by department or branch, 2016 TabLE 2. Full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in federal agencies, 2008 and 2016 TabLE 3. Full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in Ofces of Inspectors General, 2008 and 2016 TabLE 4. Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by primary function, 2016 TabLE 5. Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by sex and race or ethnicity, 2008 and 2016 TabLE 6. Sex and race or ethnicity of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in agencies employing 50 or more ofcers, other than Ofces of Inspectors General, 2016

TabLE 7. Sex and race or ethnicity of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in Ofces of Inspectors General employing 50 or more ofcers, 2016

TabLE 8. Assaults on federal law enforcement ofcers, 2008 and 2016

List of fgures

FIGURE 1. Distribution of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by department or branch, 2016 FIGURE 2. Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by primary function, 2016 FIGURE 3. Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by sex and race or ethnicity, 2008 and 2016

- Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 - Statistical Tables | October 2019

- 2

TabLE 1

Distribution of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by department or branch, 2016

Department/branch

Total Department of Homeland Security Department of Justice Other executive branch agencies Independent agencies Judicial branch

Number

132,110

62,125 43,666 15,414

4,943

Percent

100% 47.0 33.1 11.7

3.7

- 4,141

- 3.1

- 1.4

- Legislative branch

- 1,821

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016.

TabLE 2

Full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in federal agencies, 2008 and 2016

- Number of full-time

- Number of full-time

- Percent change,

- Percent of all federal

ab

Department/agency Total Ofces of Inspectors General Total executive/judicial/legislative/independent federal law enforcement agencies, other than Ofces of Inspectors General

- ofcers, 2008

- ofcers, 2016

2008-2016 ofcers, 2016

- 121,909

- 132,110

3,869

8.4%

10.1%

100%

2.9%

3,514

- 118,395

- 128,241

- 8.3%

- 97.1%

Executive departments: Department of Agriculture

Forest Service

Department of Commerce

Bureau of Industry and Security

648 103

514 108

-20.7%

4.9%

0.4% 0.1%

National Oceanic and Atmospheric

- Administration, Ofce of Law Enforcement

- 154

~~

126

38 11

-18.2

~

0.1

<0.1 <0.1

Ofce of Security Secretary’s Protective Detail

Department of Defense

~

Pentagon Force Protection Agency

Department of Energy

National Nuclear Security Administration

Department of Health and Human Services

725 363

777 302

- 7.2%

- 0.6%

- 0.2%

- -16.8%

Food and Drug Administration, Ofce of

- Criminal Investigation

- 187

94

231

77

23.5%

-18.1

0.2%

- 0.1

- National Institutes of Health, Division of Police

Department of Homeland Security

- Customs and Border Protection

- 37,482

11,779

43,724 12,400

16.7%

5.3

33.1%

9.4

c

Immigration and Customs Enforcement Federal Emergency Management Agency, Mount Weather Police Federal Protective Service

84

900

~

78

1,007

26

-7.1 11.9

~

0.1 0.8

<0.1

3.6

c

Ofce of the Chief Security Ofcer Secret Service

Department of the Interior

- 5,226

- 4,697

-10.1

Bureau of Indian Afairs, Ofce of Justice

- Services

- 277

255

21

603

1,416

547

352 253

24

619

1,822

560

27.1% -0.8 14.3

2.7

28.7

2.4

0.3% 0.2

<0.1

0.5 1.4 0.4

Bureau of Land Management Bureau of Reclamation Fish and Wildlife Service National Park Service Rangers Park Police

Continued on next page

- Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 - Statistical Tables | October 2019

- 3

TabLE 2 (continued)

Full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in federal agencies, 2008 and 2016

- Number of full-time

- Number of full-time

- Percent change,

- Percent of all federal

Department/agency Department of Justice

- ofcers, 2008

- ofcers, 2016

2008-2016 ofcers, 2016

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and

- Explosives

- 2,562

4,388

12,925 16,993

3,359

2,675 4,181

13,799 19,093

3,788

4.4%

-4.7

6.8

12.4 12.8

2.0% 3.2

10.4 14.5

2.9

Drug Enforcement Administration Federal Bureau of Investigation Federal Bureau of Prisons U.S. Marshals Service

Department of Labor

Division of Protective Operations

Department of State

Bureau of Diplomatic Security

Department of the Treasury

Bureau of Engraving and Printing Police

~

1,049

207

15

1,215

182

- ~

- <0.1%

0.9% 0.1%

15.8%

-12.1%

Internal Revenue Service, Criminal

- Investigation Division

- 2,655

316

2,198

292

-17.2

-7.6

1.7

- 0.2

- U.S. Mint Police

Department of Veterans Afairs

Police Department

- 3,175

- 3,839

- 20.9%

- 2.9%

Other federal law enforcement agencies: Administrative Ofce of the U.S. Courts

U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services

Amtrak

4,767

305 202

41

3,985

427 214

48

-16.4%

40.0%

5.9%

3.0%

- 0.3%

- Amtrak Police Department

Environmental Protection Agency

Criminal Investigation Division

Government Publishing Ofce

Uniform Police Branch

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Ofce of Protective Services

Smithsonian Institution

Ofce of Protective Services

Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States Police

Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority Police

U.S. Capitol Police

0.2%

17.1%

-17.7%

~

<0.1% <0.1%

0.5%

- 62

- 51

- ~

- 620

- 156

- 139

- 12.2%

- 0.1%

145

1,637

53

1,773

-63.4%

8.3%

<0.1%

1.3%

U.S. Postal Service

U.S. Postal Inspection Service

- 2,324

- 1,891

- -18.6%

- 1.4%

Note: Data for the Bureau of Industry and Security; the Environmental Protection Agency, Criminal Investigation Division; the Fish and Wildlife Service; and the Internal Revenue Service were obtained from fedscope.opm.gov. Data for the Federal Protective Service came from the Department of Homeland Security website. ~Not applicable. Agency was not in the 2008 Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers (CFLEO).

a

In 2008, agencies reported 1,561 full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in U.S. Territories and Commonwealths. Those ofcers are included in these numbers. The total for 2008 includes 141 ofcers from agencies that did not respond to the 2016 CFLEO.

b

In 2016, agencies reported 1,871 full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in U.S. Territories and Commonwealths. Those ofcers are included in these numbers.

c

The Federal Protective Service was included in the ofcer count for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the 2008 report. ICE reported having about 900 ofcers in the Federal Protective Service at that time, and they are listed separately in this report for both 2008 and 2016. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2008 and 2016.

- Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 - Statistical Tables | October 2019

- 4

TabLE 3

Full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in Ofces of Inspectors General, 2008 and 2016

Change,

Ofces of Inspectors General Total Executive departments:

2008

3,514

2016 2008-2016

3,869

a

355

Department of Agriculture Department of Commerce

166

16

149

12

-17

-4

Department of Defense Department of Education

345

88

328

80

-17

-8

- Department of Energy

- 48

- 64

- 16

65 30

-27

4

Department of Health and Human Services Department of Homeland Security Department of Housing and Urban Development Department of the Interior

393 163 229

66

458 193 202

70

Department of Justice Department of Labor Department of State

122 164

32

130 146

41

8

-18

9

Department of Transportation Department of the Treasury Department of Veterans Afairs

Other federal Ofces of Inspectors General:

Agency for International Development

94 21

132

102

36

171

8

15 39

13

~

36 31

23

~

b

Amtrak Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and

b

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

- ~

9

40

~

25

6

47

6

~-3

7

Corporation for National and Community Service Environmental Protection Agency

b

- Export-Import Bank of the United States

- ~

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Federal Housing Finance Agency General Services Administration Library of Congress National Aeronautics and Space Administration National Archives and Records Administration National Science Foundation

35

~

67

2

52

66

51 47 74

0

62

6

16

~7

-2 10

0

b

- 7

- 1

Ofce of Personnel Management Peace Corps Pension Beneft Guaranty Corporation

28

~~

34

55

6~~

bb

Railroad Retirement Board Securities and Exchange Commission

16

~

34

~

16 13 38

3

0~4~

b

Small Business Administration

b

Smithsonian Institution

- Social Security Administration

- 274

~

272

22

-2 ~

b

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset

b

- Relief Program

- ~

20

62 19

~

- -1

- Tennessee Valley Authority

Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration U.S. Postal Service

304 511

278 522

-26

11

~Not applicable. Agency was not in the 2008 Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers.

a

The 2008 total includes 18 ofcers from agencies that did not respond to the 2016 Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers (CFLEO).

b

Agency was not in the 2008 CFLEO. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2008 and 2016.

- Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 - Statistical Tables | October 2019

- 5

- FIGURE 2

- FIGURE 3

Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by primary function, 2016

Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by sex and race or ethnicity, 2008 and 2016

Sex

Male

Criminal investigation

Corrections

Female

Police response/patrol

Race/ethnicity

b

White

Noncriminal investigation/ enforcement

b

Black

Court operations

Hispanic

Security/protection

2008

b,c a

- 0

- 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

Other

2016

Percent

- 0

- 20

- 40

- 60

- 80

- 100

Note: See table 4 for counts and percentages.

Percent

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law

- Enforcement Ofcers, 2016.

- Note: See table 5 for estimates.

a

In 2016, federal law enforcement agencies indicated that 257 (0.2%) ofcers were of unknown race.

b

Excludes persons of Hispanic origin (e.g., “white” refers to

TabLE 4

non-Hispanic whites and “black” refers to non-Hispanic blacks).

Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers,

c

Includes Asians, Native Hawaiians, Other Pacifc Islanders, American

by primary function, 2016

Indians, Alaska Natives, and persons of two or more races. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law Enforcement

Number of Percent of

Ofcers, 2008 and 2016.

Primary function Total Police protection ofcers

132,110 100,250

82,336 11,611

6,303

total

100% 75.9% 62.3

8.8

TabLE 5

Criminal investigation Police response/patrol Non-criminal investigation/enforcement

Corrections

Percent of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers, by sex and race or ethnicity, 2008 and 2016

4.8

2008

100% 84.5 15.5 100% 65.7 10.4 19.8

2.9

2016

100% 86.3 13.7 100% 62.1 10.5 20.9

3.3

19,896

5,173

15.1%

3.9% 2.0% 3.1%

Sex

Male Female

Court operations Security/protection Function not reported

2,645 4,146

Race/ethnicity

Note: Details may not sum to totals due to rounding.

aa

White Black

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016.

Hispanic

a,b

Asian

a,b

Native Hawaiian/Other Pacifc Islander American Indian/Alaska Native Two or more races

0.1 1.0 0.1

0.3 1.0 1.6

a,b b

- Unknown race/ethnicity

- 0.0

- 0.2

Note: Details may not sum to totals due to rounding. Excludes persons of unknown race/ethnicity.

a

Excludes persons of Hispanic origin (e.g., “white” refers to non-Hispanic whites and “black” refers to non-Hispanic blacks).

b

Included in “other” in fgure 3. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2008 and 2016.

- Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 - Statistical Tables | October 2019

- 6

TabLE 6

Sex and race or ethnicity of full-time federal law enforcement ofcers in agencies employing 50 or more ofcers, other than Ofces of Inspectors General, 2016

Race/ethnicity

Native Hawaiian/ American

Sex

Male

88.1% 86.2 80.1 87.1 89.2 89.8 92.3 90.2 86.4 77.3 81.4 88.0 83.1 89.7 70.5 78.7 89.3 89.7 88.9

100.0

88.0 92.1 90.1 76.3

- Other Pacifc

- Indian/Alaska Two or

- Agency

- Number

43,724 19,093 13,799 12,400

4,729 4,181 3,839 3,788 2,675 1,891 1,773 1,215 1,119

777

- Total

- Female

11.9% 13.8 19.9 12.9 10.8 10.2

7.7

- Total

- White*

49.9% 60.5 83.3 61.4 76.2 79.1 62.4 77.1 80.0 56.6 59.9 78.9 88.2 51.9

9.2

77.0 77.3 69.6

2.8

84.4 67.5 85.4 37.9 73.7

Black*

4.9%

22.0

4.9 7.4

13.1

7.8

22.9

8.6 8.0

21.5 30.3

5.3

Hispanic

39.5%

8.6 6.3

25.5

6.8 8.9

10.3

9.6 4.4

14.2

6.4 8.1 5.0 2.8 8.1 8.4 5.9 9.6 0.6

Asian*

4.1% 1.2 4.2 5.0 2.5 2.8 2.2 2.0 1.9 6.0 2.5 3.6 1.7 1.4 2.1 1.2 3.0 2.1 0.0 1.7 4.8 1.2 2.2 1.9

- Islander*

- Native*