The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postmodernism: the American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document

Postmodernism: The American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document Tyron Tyson Smith1; Ajit Duara2* 1Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*[email protected] Abstract Postmodernism is a movement that grew out of modernism. Movements in art, literature, and cinema focused on a particular stance. The visual artists who created entertainment focused on expressing the creator herself/himself beginning from German expressionism to modernism, surrealism, cubism, etc. These art movements played an important part in what an artist (literature, art, and visual) portrayed to his or her audience. As perspectives played an important part, an understanding of what the artist needed to portray was critical. Modernism dealt with this portrayal, which came about due to the changes taking place in society. In terms of the industry, where the overall product dealt with features like individualism, experimentation and absurdity, modernism dealt with a need to overthrow past notions of what painting, literature, and the visual arts needed to be. "After World War II, the focus moved from Europe to the United States, and abstract expressionism (led by Jackson Pollock) continued the movement's momentum, followed by movements such as geometric abstractions, minimalism, process art, pop art, and pop music." Postmodernism helped do away with these shortcomings. An understanding of postmodernism is explored in this paper. The main point which sets it apart is concepts like pastiche, intersexuality, and spectacle. Concerning pop culture, an understanding of referencing is a constant trait used by postmodern art. -

Of Becoming and Remaining Vegetarian

Wang, Yahong (2020) Vegetarians in modern Beijing: food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/77857/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Vegetarians in modern Beijing: Food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience Yahong Wang B.A., M.A. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow March 2019 1 Abstract This study investigates how self-defined vegetarians in modern Beijing construct their identity through everyday experience in the hope that it may contribute to a better understanding of the development of individuality and self-identity in Chinese society in a post-traditional order, and also contribute to understanding the development of the vegetarian movement in a non-‘Western’ context. It is perhaps the first scholarly attempt to study the vegetarian community in China that does not treat it as an Oriental phenomenon isolated from any outside influence. -

Animals and Ethics Fall, 2017, P

Philosophy 174a Ethics and Animals Fall 2017 Instructor: Teaching Fellow: Chris Korsgaard Ahson Azmat 205 Emerson Hall [email protected] [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays 1:30-3:30 Description: Do human beings have moral obligations to the other animals? If so, what are they, and why? Should or could non-human animals have legal rights? Should we treat wild and domestic animals differently? Do human beings have the right to eat the other animals, raise them for that purpose on factory farms, use them in experiments, display them in zoos and circuses, make them race or fight for our entertainment, make them work for us, and keep them as pets? We will examine the work of utilitarian, Kantian, and Aristotelian philosophers, and others who have tried to answer these questions. This course, when taken for a letter grade, meets the General Education requirement for Ethical Reasoning. Sources and How to Get Them: Many of the sources from we will be reading from onto the course web site, but you will need to have copies of Singer’s Animal Liberation, Regan’s The Case for Animal Rights, Mill’s Utilitarianism and Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals. I have ordered all the main books from which we will be reading (except my own book, which is not yet published) at the Coop. The main books we will be using are: Animal Liberation, by Peter Singer. Updated edition, 2009, by Harper Collins Publishers. The Case for Animal Rights, by Tom Regan. University of California Press, 2004. Fellow Creatures: Our Obligations to the Other Animals, by Christine M. -

FAMILY GUY “The Glenn Beck Quagmire”

FAMILY GUY “The Glenn Beck Quagmire” Written by Marcos Luevanos Marcos Luevanos (626) 485-2140 [email protected] ACT ONE EXT./ESTAB. GRIFFINS’ HOUSE - DAY INT. GRIFFINS’ LIVING ROOM - SAME PETER blasts an air horn. PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Hurry it up you guys! The world and I have waited long enough for “Pretty Woman 2: Reality Sets In.” INT. SUBURBAN HOME - MORNING (CUTAWAY) A sloppily dressed RICHARD GERE yells at a crying JULIA ROBERTS. TWO CHILDREN observe from the staircase. RICHARD GERE I’m not getting what the problem is. You knew I slept with hookers when you married me. (SCOFFS) That’s how we met! INT. GRIFFINS’ LIVING ROOM - DAY (BACK TO SCENE) The doorbell rings. Peter opens it to reveal an incredibly ill QUAGMIRE. PETER Hey Quagmire! (DISGUSTED) Whoa, you look worse than Lindsay Lohan in a well-lit room. FAMILY GUY - "The Glenn Beck Quagmire" 2. QUAGMIRE That bad, huh? I have an appointment at the free clinic but I can’t seem to, you know, see. Would you be able to give me a ride to the doctor? PETER Sure thing. I was running low on free condoms anyway. (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Hey slowpokes, eighty-six the movie, I’m taking Quagmire to get his junk checked out. LOIS (O.S.) What? PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) I said, I’m taking Quagmire to get his junk checked out. (NORMAL, TO QUAGMIRE) It is your junk, right? QUAGMIRE Right. PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Yeah, it’s his junk. Quagmire smacks his forehead. FAMILY GUY - "The Glenn Beck Quagmire" 3. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Vegetarian Nutrition Resource List April 2008

Vegetarian Nutrition Resource List April 2008 This publication is a compilation of resources on vegetarian nutrition. The resources are in a variety of information formats: articles, pamphlets, books and full-text materials on the World Wide Web. Resources chosen provide information on many aspects of vegetarian nutrition. Materials included in this list may also be available to borrow from the National Agricultural Library (NAL). Lending and copy service information is provided at the end of this document. If you are not eligible for direct borrowing privileges, check with your local library on how to borrow through interlibrary loan. Materials cannot be purchased from NAL. Contact information is provided if you wish to purchase any materials on this list. This Resource List is available from the Food and Nutrition Information Center’s (FNIC) Web site at: http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/pubs/bibs/gen/vegetarian.pdf. A complete list of FNIC publications can be found at http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/resource_lists.shtml. Table of Contents: A. General Information on Vegetarian Nutrition 1. Articles and Pamphlets 2. Books 3. Magazines and Newsletters 4. Web Resources B. Vegetarian Diets and Disease Prevention and Treatment 1. Articles and Pamphlets 2. Books 3. Web Resources C. Vegetarian Diets for Special Populations 1. Vegetarianism During the Lifecycle a. Resources for Pregnancy and Lactation b. Resources for Infants and Children c. Resources for Adolescents d. Resources for Older Americans e. Resources for Athletes D. Vegetarian Cooking and Foods 1. Books 2. Web Resources E. Resource Centers A. General Information on Vegetarian Nutrition 1. Articles and Pamphlets Vegetarian Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group Newsletter Full Text: http://www.andrews.edu/NUFS/vndpg.html Description: 18 articles from the Vegetarian Nutrition DPG Newsletter on many aspects of vegetarianism including articles on various diseases, education and essential nutrients. -

A Non-Violent Politics? Vegetarianism, Religion, and the State in Eighteenth-Century Western India

Divya Cherian, Draft: Please do not cite or quote without the author’s permission. A Non-Violent Politics? Vegetarianism, Religion, and the State in Eighteenth-Century Western India Divya Cherian Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow Rutgers Center for Historical Analysis Scholarly discussions of the place of non-human animals in Hindu and Jain ethics, ritual, and everyday life generally place the principle of ahimsā or non-injury at the very center. An adherence to non-injury is an ethical injunction imposed by these two major South Asian religions (in addition to Buddhism) upon their practitioners. In principle, the Jain, Buddhist, and Vaishnav insistence upon non-injury is a universal one, that is, their ethical codes do not make a distinction between human and non-human animals as objects of compassion and non-injury. At the same time, Hindu and Jain attitudes towards animals are complex, even inconsistent. While in certain respects, neither Hindu nor Jain thought draws a distinction between the jiv (soul) of a human and a non-human, both religions do in other contexts differentiate among and hierarchize different types of beings. Taking differences in the potential to attain liberation from the cycle of birth-death-rebirth as the metric, both Jainism and Hinduism place humans at the pinnacle of a hierarchical conception of life forms. Despite this complexity in their approach to the distinction between humans and animals, the law codes of Jainism and several strands of Hinduism nonetheless enjoin upon their followers an adherence to non-injury towards all life forms. This however was not always the case. -

219 No Animal Food

219 No Animal Food: The Road to Veganism in Britain, 1909-1944 Leah Leneman1 UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH There were individuals in the vegetarian movement in Britain who believed that to refrain from eating flesh, fowl, and fish while continuing to partake of dairy products and eggs was not going far enough. Between 1909 and 1912, The Vegetarian Society's journal published a vigorous correspond- ence on this subject. In 1910, a publisher brought out a cookery book entitled, No Animal Food. After World War I, the debate continued within the Vegetarian Society about the acceptability of animal by-products. It centered on issues of cruelty and health as well as on consistency versus expediency. The Society saw its function as one of persuading as many people as possible to give up slaughterhouse products and also refused journal space to those who abjured dairy products. The year 1944 saw the word "vergan" coined and the breakaway Vegan Society formed. The idea that eating animal flesh is unhealthy and morally wrong has been around for millennia, in many different parts of the world and in many cultures (Williams, 1896). In Britain, a national Vegetarian Society was formed in 1847 to promulgate the ideology of non-meat eating (Twigg, 1982). Vegetarianism, as defined by the Society-then and now-and by British vegetarians in general, permitted the consumption of dairy products and eggs on the grounds that it was not necessary to kill the animal to obtain them. In 1944, a group of Vegetarian Society members coined a new word-vegan-for those who refused to partake of any animal product and broke away to form a separate organization, The Vegan Society. -

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

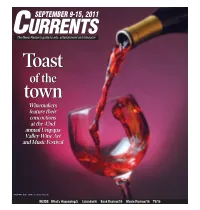

Layout 1 (Page 2)

SEPTEMBER 9-15, 2011 CCURRENTSURRENTS The News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television ToastToast ofof thethe towntown WinemakersWinemakers featurefeature theirtheir concoctionsconcoctions atat thethe 42nd42nd annualannual UmpquaUmpqua ValleyValley WineWine ArtArt andand MusicMusic FestivalFestival MICHAEL SULLIVAN/The News-Review INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/4 Book Review/10 Movie Review/14 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 * &YJUt$BOZPOWJMMF 03t*OGPt3FTtTFWFOGFBUIFSTDPN Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 The News-Review, Page 3 what’s HAPPENING TENMILE An artists’ reception will be held from 5 to 7 p.m. Friday at Remembering GEM GLAM the gallery, 638 W. Harrison St., Roseburg. 9/11 movie, songs Also hanging is art by pastel A special 9/11 remembrance painter Phil Bates, mixed event will be held at 5 p.m. media artist Jon Leach and Sunday at the Tenmile Com- acrylic painter Holly Werner. munity United Methodist Fisher’s is open regularly Church, 2119 Tenmile Valley from 9 to 5 p.m. Monday Road. through Friday. The event includes a show- Information: 541-817-4931. ing of a one-hour movie, “The Cross and the Towers,” fol- lowed by patriotic music and MYRTLE CREEK sing-alongs with musicians Mark Baratta and Scott Van Local artist’s work Atta. hangs at gallery The event is free, but dona- Myrtle Creek artist Darlene tions for musicians’ expenses Musgrave is the featured artist are welcome. Refreshments at Ye Olde Art Shoppe. will be served. An artist’s reception for Information: 541-643-1636. Musgrave will be held from 10 a.m. -

A Cultural Study of Gendered Onscreen

VEG-GENDERED: A CULTURAL STUDY OF GENDERED ONSCREEN REPRESENTATIONS OF FOOD AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR VEGANISM by Paulina Aguilera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts & Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2014 Copyright by Paulina Aguilera, 2014 11 VEG-GENDERED: A STUDY OF GENDERED ONSCREEN REPRESENTATIONS OF FOOD AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR VEGANISM by Paulina Aguilera This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Dr. Christine Scodari, School of Communication and Multimedia Studies, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ~t~;,~ obe, Ph.D. David C. Williams, Ph.D. Interim Director, School of Communication and Multimedia Studies Heather Coltman, DMA Dean, ;~~of;candLetters 0'7/0 /:fdf4 8 ~T.Fioyd, Ed.D~ -D-at_e _ _,__ ______ Interim Dean, Graduate College 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Christi ne Scodari for her incredible guidance and immeasurable patience during the research and writing of this thesis. Acknowledgements are also in order to the participating committee members, Dr. Chris Robe and Dr. Fred Fejes, who provided further feedback and direction. Lastly, a special acknowledgement to Chandra Holst-Maldonado is necessary for her being an amazing source of moral support throughout the thesis process. -

Replace Them by Salads and Vegetables”: Dietary Innovation, Youthfulness, and Authority, 1900–1939

Global Food History ISSN: 2054-9547 (Print) 2054-9555 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfgf20 “Replace them by Salads and Vegetables”: Dietary Innovation, Youthfulness, and Authority, 1900–1939 James F. Stark To cite this article: James F. Stark (2018) “Replace them by Salads and Vegetables”: Dietary Innovation, Youthfulness, and Authority, 1900–1939, Global Food History, 4:2, 130-151, DOI: 10.1080/20549547.2018.1460538 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20549547.2018.1460538 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 23 Apr 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 149 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfgf20 GLOBAL FOOD HISTORY 2018, VOL. 4, NO. 2, 130–151 https://doi.org/10.1080/20549547.2018.1460538 OPEN ACCESS “Replace them by Salads and Vegetables”: Dietary Innovation, Youthfulness, and Authority, 1900–1939 James F. Stark School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The events of the First World War fueled public fascination with Received 3 January 2017 rejuvenation at the same time as medical scientists began to explore Accepted 27 February 2018 the physiological potential of so-called “vitamine.” The seemingly KEYWORDS bottomless capacity of vitamins to maintain bodily function and Vitamins; diet; fasting; aging; appearance offered a possible mechanism for achieving bodily youth; rejuvenation renewal, alongside established dietary practices such as abstention from alcohol and meat. Drawing on mainstream medical publications, popular dietary texts and advertising materials, this paper outlines how vitamins and other dietary practices played an important but hitherto unrecognized role in reconfiguring ideas about anti-aging and rejuvenation.