Retro from the Get-Go: Reactionary Reflections on Marketing's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwell Leaves News and Information from Southwell Minster

Southwell Leaves News and Information from Southwell Minster August/September 2020 £2.50 Follow us on twitter @SouthwMinster www.southwellminster.org Contents… Southwell Minster’s Dragonfly Southwell Minster’s Dragonfly 2 Jill Lucas Subscription 2 mages of birds, animals and plants are frequently found in places of Welcome / Pause for Thought 3 I worship, from small village churches to imposing abbeys, cathedrals and minsters. They may have been chosen for their symbolism as in the From the Dean - Writing History 4 butterfly’s life cycle, where the larva symbolises life, its pupa death, and the Update on Chapter House Leaves project 4 adult insect resurrection. The subjects were rarely made from metal. Homecoming for weary souls 5 Bees, beetles, butterflies and flies were of religious significance and are not uncommon, but so far, the dragonfly appears to have no such position, Living at Three Miles per Hour 6 although it is found decorating the margins of psalters, missals and Books of Hours, for example the Lutterall Psalter dating from c. 1340. The 5-bar gate 7 Pre-dating the building of the Minster’s Chapter House (circa 1280) a God and the Coronavirus 8 vestibule linked the nave to an outside baptismal pool via a trumeau or gate. Bible Verses for Reflection 8 It is suggested that a pillar from this gate was moved at a later date to its present position between the Quire and the vestibule leading to the Chapter What if 2020 is the year we’ve been House. waiting for ? 9 Decorating the pillar is an iron carving, hinged on one side, of a so far unidentified creature. -

Starkin a Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts in Creative Writing

Starkin A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts in Creative Writing Degree The University of Tennessee, Chattanooga Rebecca W. Miller March 20 Copyright 2010 by Rebecca W. Miller All rights reserved. Acknowledgment I would like to say thank you to all the professors at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga who helped me complete my thesis. Sybil Baker, Thomas Balazs, Earl Braggs, Joyce Smith and many others have helped influence my writing for the better over the last few years. I appreciate the opportunity to work with them to realize my dream of completing my master‘s degree. Also, I could not have survived the trials of graduate school along with my full-time job if it were not for the endless support of my friends and family. I am very happy that I could count on Mom, Dad, Alex, Grandma, Fundy, Crystal and Holly to give me their full support as well as a kick in the pants when needed. Abstract In traditional fantasy novels, as established with J.R.R. Tolkien‘s Lord of the Rings, the main character embarks on a heroic journey. As defined by Joseph Campbell, who was the author, editor and translator of books on mythology such as The Hero with a Thousand Faces a heroic journey is an epic quest that leads the hero physically to an internal rebirth. Within Campbell‘s study of the monomyth, using those conventions outlined by Campbell, I will show how Tolkien elements uses Campbell‘s conventions in Middle Earth, where a simple young hobbit ends up saving his world. -

Readers' Guide

Readers’ Guide for by J.R.R. Tolkien ABOUT THE BOOK Bilbo Baggins is a hobbit— a hairy-footed race of diminutive peoples in J.R.R. Tolkien’s imaginary world of Middle-earth — and the protagonist of The Hobbit (full title: The Hobbit or There and Back Again), Tolkien’s fantasy novel for children first published in 1937. Bilbo enjoys a comfortable, unambitious life, rarely traveling any farther than his pantry or cellar. He does not seek out excitement or adventure. But his contentment is dis- turbed when the wizard Gandalf and a company of dwarves arrive on his doorstep one day to whisk him away on an adventure. They have launched a plot to raid the treasure hoard guarded by Smaug the Magnificent, a large and very dangerous dragon. Bilbo reluctantly joins their quest, unaware that on his journey to the Lonely Mountain he will encounter both a magic ring and a frightening creature known as Gollum, and entwine his fate with armies of goblins, elves, men and dwarves. He also discovers he’s more mischievous, sneaky and clever than he ever thought possible, and on his adventure, he finds the courage and strength to do the most surprising things. The plot of The Hobbit, and the circumstances and background of magic ring, later become central to the events of Tolkien’s more adult fantasy sequel, The Lord of the Rings. “One of the best children’s books of this century.” — W. H. AUDEN “One of the most freshly original and delightfully imaginative books for children that have appeared in many a long day . -

Pub Or Supermarket?

June 2014 issue 109 InnSpire THE MAGAZINE OF CHESTERFIELD AND DISTRICT CAMRA The future for The Crispin PUB OR SUPERMARKET? FREEPage 1 COPY InnSpire Editorial & Production Chesterfield & District Tim Stone & Debbie Jackson CAMRA Tel: 07773 141433 [email protected] Chairman Advertisements Mick Portman Peter Boitoult 88 Walton Road, Chesterfield S40 3BY Tel: 07791 159 526 Tel: 01246 277757 [email protected] Further Information Branch Contact www.innspire.org.uk Jane Lefley [email protected] [email protected] Article Deadline for August 07790 863432 Issue 110 Wobble Organisers Friday 18th July 2014 Ray Easter InnSpire has a circulation of 4,250 [email protected] copies and is produced by and copyright of the Chesterfield & District Colin Clark Branch of CAMRA. [email protected] Matlock & Dales Branch No parts may be used without permission. Articles & letters are Contact always welcome and may be Peter Boitoult 07791 159 526 submitted by email to the InnSpire Editor, address above. Do you have trouble Please note that the views expressed finding a copy of InnSpire? herein are those of individual contributors and not necessarily those Why not guarantee yourself a copy by of the national Campaign for Real Ale subscribing to our Postal List? or the local Branch. As each issue is published, you will Chesterfield & District CAMRA is a be one of the first to receive a copy of Branch of the Campaign for Real Ale InnSpire, directly to your door. To receive a whole year’s worth of InnSpire, please send six second class LARGE letter stamps to: InnSpire Postal List, 88 Walton Road, Chesterfield S40 3BY Please remember to include your full name and address. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

Residents Associations

Residents Associations Ashurst Park Residents Association Bellevue Residents Association Bitterne Park Residents Association Blackbushe, Pembrey & Wittering Residents Association Blackbushe, Pembrey & Wittering Residents Association Channel Isles and District Tenants and Residents Association Chapel Community Association Clovelly Rd RA East Bassett Residents Association Flower Roads Residents and Tenants Association Freemantle Triangle Residents Association Graham Road Residents Association Greenlea Tenant and Residents Association Hampton Park Residents Association Harefield Tenants and Residents Association Highfield Residents Association Holly Hill Residents Association Hum Hole Project Itchen Estate Tenants and Residents Association Janson Road RA LACE Tenant and Residents Association Leaside Way Residents Association Lewis Silkin and Abercrombie Gardens Residents Association Lumsden Ave Residents Association Mansbridge Residents Association Maytree Link Residents Association Newlands Ave Residents Association Newtown Residents Association North East Bassett Residents Association Northam Tenants and Residents Association Old Bassett Residents Association Outer Avenue Residents Association Pirrie Close & Harland Crescent Residents Association Portswood Gardens Resident association Redbridge Residents Association Riverview Residents Association Rockstone Lane Residents Association Ropewalk RA Southampton Federation of Residents Associations Stanford Court Tenants and residents Association Thornbury Avenue & District Residents Association -

Airport Lease Plan on Hold in Santa Monica

PROMOTE YOUR BUSINESS HERE! Yes, in this very spot! Call for details (310) 458-7737 MONDAY,AUGUST 18, 2014 Volume 13 Issue 233 Santa Monica Daily Press KNOW BEFORE YOU GO SEE PAGE 3 We have you covered THE HASHTAG ISSUE Twitter opening office Airport lease plan on hold in Santa Monica BY DAVID MARK SIMPSON flight schools and mechanics, work in the erence to those who say they will comply. BY DAVID MARK SIMPSON Daily Press Staff Writer aviation field. Others, like theaters and art During the public portion of the meet- Daily Press Staff Writer studios, don’t. ing, several sub-tenants of the Santa SMO City Council wasn’t ready to pull the Residents near the airport have long Monica Art Studios asked that their studio’s PICO BLVD Twitter, the short-form social trigger on recommendations that would complained about the pollution and noise lease be extended, and that they be given networking service, is opening an office on have extended aviation leases at the Santa caused by the aircraft. Others fear for their longer terms. Pico Boulevard at Main Street. Monica Airport and raised all leases to safety with the runway located just a few It should be noted that the owners of City Hall issued the company a business market rate. hundred feet from homes. these particular art studios were given leas- license for 150 Pico Blvd. back in June. It lists Instead, council voted unanimously at Advocates of SMO say it would be essen- es on publicly owned land at well-below the company’s start date as Aug. -

Small Group 2020 V2.Indd

ONE OF A KIND ESCORTED GROUP TOURS Membership limited to maximum 14 travelers A collection of 2020 Travel Experiences Bhutan & Nepal | Colombia | Israel, Petra, Egypt | Italy | New Zealand The Lakani World Tours logo is intentional in its design. The four directional points represents our experience in travel to the far corners of the world, as well as the four fundamental principles which guide each program we create. Every Lakani World Tours program includes the best sightseeing and services that the area has to offer. While we recognize that quality does not come cheaply, we provide value through our experience and strong relationships with proven suppliers. The Lakani team provides honest answers, objective advice and strong commitments. We also offer the usual industry assurances and safeguards: we are a registered California Seller of Travel. Naturally, references are available. The Lakani team of seasoned industry veterans draws from their experience and their never ending quest to uncover new and unusual sights, activities and lodging to share with travelers. We believe that attitude is everything. Service begins the first time you call us and continues throughout your entire journey. The Lakani Travel Specialists and its team of expert Tour Managers consistently endeavor to anticipate the desires and expectations of every Lakani traveler. A Letter From The President Dear World Travelers, It is with great pleasure that we present to you our collection of Group Tours for 2020. These itineraries are crafted to meet the needs of those travelers that enjoy traveling in the company of like-minded people, some of whom form long-lasting friendships. -

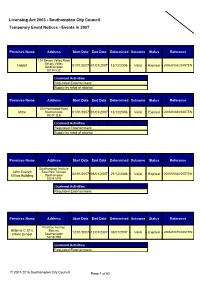

Tens by Date

Licensing Act 2003 - Southampton City Council Temporary Event Notices - Events in 2007 Premises Name Address Start Date End Date Determined Outcome Status Reference 134 Bevois Valley Road Bevois Valley 2006/00382/04STEN Hobbit Southampton 01/01/2007 01/01/2007 13/12/2006 Valid Expired SO14 0JZ Licensed Activities Regulated Entertainment Supply by retail of alcohol Premises Name Address Start Date End Date Determined Outcome Status Reference 200 Portswood Road Mitre Southampton 01/01/2007 01/01/2007 13/12/2006 Valid Expired 2006/00380/04STEN SO17 2LB Licensed Activities Regulated Entertainment Supply by retail of alcohol Premises Name Address Start Date End Date Determined Outcome Status Reference Southampton Institute John Everett East Park Terrace 04/01/2007 06/01/2007 21/12/2006 Valid Expired 2006/00388/04STEN Millais Building Southampton SO14 0YN Licensed Activities Regulated Entertainment Premises Name Address Start Date End Date Determined Outcome Status Reference Peartree Avenue Bitterne C Of E Bitterne 12/01/2007 12/01/2007 05/01/2007 Valid Expired 2006/00375/04STEN Infant School Southampton SO19 7RB Licensed Activities Regulated Entertainment © 2007-2016 Southampton City Council Page 1 of 62 Premises Name Address Start Date End Date Determined Outcome Status Reference Freemantle Randolph Street Community Southampton 12/01/2007 13/01/2007 21/11/2006 Valid Expired 2006/00344/04STEN Centre SO15 3HD Licensed Activities Regulated Entertainment Premises Name Address Start Date End Date Determined Outcome Status Reference Bargate Bargate -

Celebrity Book Stacks

www.mississauga.ca/library Updated by: Readers’ Den Department - Mississauga Library System As a special project to promote literacy in the community, famous Canadians donated their favourite book to the Library. These books are on permanent display in the Readers' Den department at the Central Library on the main level. Slowly Down the Ganges by Eric Nobody Knows My Name by James Newby Baldwin Donated by Allen Abel, Author and Donated by Lincoln Alexander, Former News Reporter Ontario Lieutenant-Governor The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery Donated by Reverend Aloysius Donated by Lisa Alexander, Canadian Ambrozic, Catholic Archbishop of Olympic Medallist, Synchronized Toronto Swimmer Regina, an Illustrated History by Nucleus by Atomic Energy of Canada J.William Brennan Ltd. Donated by Mayor Douglas R. Archer, Mayor of Regina Donated by Robert Bothwell, History professor, University of Toronto The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret The Hobbit by J.R.R.Tolkien Atwood Donated by Angela Bailey, Canadian Donated by Margaret Atwood, Athlete (track & field) Canadian Author The World of Robert Bateman by The Little Prince by A. De Robert Bateman Saint-Exupery Donated by Robert Bateman, Donated by Frank Bean, Regional Canadian Nature Artist chairman, Peel region The Secret World of Og by Pierre The Covenant by James A. Michener Berton Donated by Don Blenkarn, Lawyer, Donated by Pierre Berton, Canadian Former Politician Author Le Grand Meaulnes by Alain Fournier The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell Donated by Benoit Bouchard, Canada's Ambassador to France Donated by Liona Boyd, Canadian Musician Anne of Green Gables by L.M. -

A Comparative Analysis of J.R.R Tolkien's the Hobbit

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 16, 2020 A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF J.R.R TOLKIEN’S THE HOBBIT AND IT’S FILM ADAPTATION T. Gokulapriya1, Dr. S. Selvalakshmi 1Ph D Scholar in English Dept, Karpagam Academy of Higher Education, Coimbatore, India 2Professor & Head, Department of English , Karpagam Academy of Higher Education ,Coimbatore, India E-mail: [email protected] 1, [email protected] Received: 14 March 2020 Revised and Accepted: 8 July 2020 ABSTRACT: Every human being has the power of imagination, which most people use to think about life and make plans for their future. But, mostly, they do not think beyond the real world. Only a few people like novelists and scientists give more importance to their creativity. In fantasy novels, imaginative power is the key element to unlock a story which is stored in the mind. The author gives soul to the story with his imagination. J.R.R. Tolkien, a well-known twentieth century British writer, has used his incomparable imaginative power to create a new world ‗Middle-Earth‘ and a new creature like hobbit, a fictional character. ―In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit‖ (The Hobbit 3). Tolkien created Middle-Earth and fictional characters inspired by Anglo- Saxon literature when he was working as a professor of English Language and Literature in Merton College, Oxford. I. INTRODUCTION Fantasy has become a major area of profit-making fiction. Tolkien‘s The Hobbit is inscription on behalf of both kids and adult readers. The Hobbit is a fantasy novel influenced by the myths and languages of Northern European literature. -

Village Approves Publix by DAVID GOODHUE Essary Commercial Square It’S the First Chain Store Going in Than $1 Million Do Defend

WWW.KEYSINFONET.COM SATURDAY, DECEMBER 14, 2013 VOLUME 60, NO. 100 G 25 CENTS ISLAMORADA Village approves Publix By DAVID GOODHUE essary commercial square It’s the first chain store going in than $1 million do defend. ers stopped letting people [email protected] footage from the village, it Councilman David Purdo inside. The one issue alone would be the first retail since big-box lawsuit was struck said at Thursday’s council was debated by residents and Publix received preliminary chain supermarket built in meeting that he feels that rul- attorneys on both sides for approval from Islamorada’s incorporated Islamorada’s lawsuit, developers of a pro- Circuit Court of Appeals ing opened the door to busi- more than five hours. Village Council Thursday 15-year history. posed Walgreens drug store at judge ruled that Islamorada nesses like Publix. Most speaking against the night to build a 28,000-square- The affirmative vote on mile marker 82 were denied already had chain stores like About 100 people packed project said they think Publix, foot supermarket on Upper Publix’s site plan is arguably because of the so-called “for- Ace Hardware and Eckerd’s into Islamorada’s Village Hall planned for a site at mile mark- Matecumbe Key. the partial result of a federal mula retail” ordinance. Drugs Store (now CVS), so at Founders Park to either er 82.5 bayside, is a quality If the store makes it past a court’s 2008 ruling against a The law’s purpose was to basically, there was no small- support or protest the pro- company but think the project series of regulatory steps, 2002 village law designed to protect the village’s small- town character to protect.