Viking Warrior Women?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vikings Chapter

Unit 1 The European and Mediterranean world The Vikings In the late 8th century CE, Norse people (those from the North) began an era of raids and violence. For the next 200 years, these sea voyagers were feared by people beyond their Scandinavian homelands as erce plunderers who made lightning raids in warships. Monasteries and towns were ransacked, and countless people were killed or taken prisoner. This behaviour earned Norse people the title Vikingr, most probably meaning ‘pirate’ in early Scandinavian languages. By around 1000 CE, however, Vikings began settling in many of the places they had formerly raided. Some Viking leaders were given areas of land by foreign rulers in exchange for promises to stop the raids. Around this time, most Vikings stopped worshipping Norse gods and became Christians. 9A 9B How was Viking society What developments led to organised? Viking expansion? 1 Viking men spent much of their time away from 1 Before the 8th century the Vikings only ventured home, raiding towns and villages in foreign outside their homelands in order to trade. From the lands. How do you think this might have affected late 8th century onwards, however, they changed women’s roles within Viking society? from honest traders into violent raiders. What do you think may have motivated the Vikings to change in this way? 226 oxford big ideas humanities 8 victorian curriculum 09_OBI_HUMS8_VIC_07370_TXT_SI.indd 226 22/09/2016 8:43 am chapter Source 1 A Viking helmet 9 9C What developments led to How did Viking conquests Viking expansion? change societies? 1 Before the 8th century the Vikings only ventured 1 Christian monks, who were often the target of Viking outside their homelands in order to trade. -

How to Train Your Dragon: Pre‐Reading

How to Train Your Dragon: Pre‐reading Social & Historical Context When we study English at secondary level, it is often useful to find out about the social and historical contexts that surround what we are reading. We look at the key events in history and society that took place during the time a text was written or set. We then question how this context may have influenced the presentation of: events, characters and ideas. ‘How to Train Your Dragon,’ was published in 2003 but it is set on the fictional island of Berk during the age of the Vikings. Before we start reading the novel, let’s explore some context. Read the contextual information and complete the activities below. Who were the Vikings? The Vikings, also called Norsemen, came from all around Scandinavia (where Norway, Sweden and Denmark are today). They sent armies to Britain about the year 700 AD to take over some of the land, and they lived here until around 1050. Even though the Vikings didn’t stay in Britain, they left a strong mark on society – we’ve even kept some of the same names of towns. They had a large settlement around York and the Midlands, and you can see some of the artefacts from Viking settlements today. The word ‘Viking’ means ‘a pirate raid’ in the Norse language, which is what the Vikings spoke. Some of the names of our towns and villages have a little bit of Norse language in them. Do you recognise any names with endings like these: ‘‐by’ (as in Corby or Whitby, means ‘farm’ or ‘town’) and ‘‐thorpe’ (as in Scunthorpe) means ‘village.’ The Viking alphabet, ‘Futhark’, was made up of 24 characters called runes. -

Saami and Scandinavians in the Viking

Jurij K. Kusmenko Sámi and Scandinavians in the Viking Age Introduction Though we do not know exactly when Scandinavians and Sámi contact started, it is clear that in the time of the formation of the Scandinavian heathen culture and of the Scandinavian languages the Scandinavians and the Sámi were neighbors. Archeologists and historians continue to argue about the place of the original southern boarder of the Sámi on the Scandinavian peninsula and about the place of the most narrow cultural contact, but nobody doubts that the cultural contact between the Sámi and the Scandinavians before and during the Viking Age was very close. Such close contact could not but have left traces in the Sámi culture and in the Sámi languages. This influence concerned not only material culture but even folklore and religion, especially in the area of the Southern Sámi. We find here even names of gods borrowed from the Scandinavian tradition. Swedish and Norwegian missionaries mentioned such Southern Sámi gods such as Radien (cf. norw., sw. rå, rådare) , Veralden Olmai (<Veraldar goð, Frey), Ruona (Rana) (< Rán), Horagalles (< Þórkarl), Ruotta (Rota). In Lule Sámi we find no Scandinavian gods but Scandinavian names of gods such as Storjunkare (big ruler) and Lilljunkare (small ruler). In the Sámi languages we find about three thousand loan words from the Scandinavian languages and many of them were borrowed in the common Scandinavian period (550-1050), that is before and during the Viking Age (Qvigstad 1893; Sammallahti 1998, 128-129). The known Swedish Lapponist Wiklund said in 1898 »[...] Lapska innehåller nämligen en mycket stor mängd låneord från de nordiska språken, av vilka låneord de äldsta ovillkorligen måste vara lånade redan i urnordisk tid, dvs under tiden före ca 700 år efter Kristus. -

Witches, Pagans and Historians. an Extended Review of Max Dashu, Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1000

[The Pomegranate 18.2 (2016) 205-234] ISSN 1528-0268 (print) doi: 10.1558/pome.v18i2.32246 ISSN 1743-1735 (online) Witches, Pagans and Historians. An Extended Review of Max Dashu, Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1000 Ronald Hutton1 Department of Historical Studies 13–15 Woodland Road Clifton, Bristol BS8 1TB United Kingdom [email protected] Keywords: History; Paganism; Witchcraft. Max Dashu, Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1000 (Richmond Calif.: Veleda Press, 2016), iv + 388 pp. $24.99 (paper). In 2011 I published an essay in this journal in which I identified a movement of “counter-revisionism” among contemporary Pagans and some branches of feminist spirituality which overlapped with Paganism.2 This is characterized by a desire to restore as much cred- ibility as possible to the account of the history of European religion which had been dominant among Pagans and Goddess-centered feminists in the 1960s and 1970s, and much of the 1980s. As such, it was a reaction against a wide-ranging revision of that account, largely inspired by and allied to developments among professional historians, which had proved influential during the 1990s and 2000s. 1. Ronald Hutton is professor of history, Department of History, University of Bristol 2. “Revisionism and Counter-Revisionism in Pagan History,” The Pomegranate, 13, no. 2 (2011): 225–56. In this essay I have followed my standard practice of using “pagan” to refer to the non-Christian religions of ancient Europe and the Near East and “Pagan” to refer to the modern religions which draw upon them for inspiration. -

18Th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017

18th Viking Congress Denmark, 6–12 August 2017 Abstracts – Papers and Posters 18 TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 2 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS Sponsors KrKrogagerFondenoagerFonden Dronning Margrethe II’s Arkæologiske Fond Farumgaard-Fonden 18TH VIKING CONGRESS, DENMARK 6–12 AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACTS – PAPERS AND POSTERS 3 Welcome to the 18th Viking Congress In 2017, Denmark is host to the 18th Viking Congress. The history of the Viking Congresses goes back to 1946. Since this early beginning, the objective has been to create a common forum for the most current research and theories within Viking-age studies and to enhance communication and collaboration within the field, crossing disciplinary and geographical borders. Thus, it has become a multinational, interdisciplinary meeting for leading scholars of Viking studies in the fields of Archaeology, History, Philology, Place-name studies, Numismatics, Runology and other disciplines, including the natural sciences, relevant to the study of the Viking Age. The 18th Viking Congress opens with a two-day session at the National Museum in Copenhagen and continues, after a cross-country excursion to Roskilde, Trelleborg and Jelling, in the town of Ribe in Jylland. A half-day excursion will take the delegates to Hedeby and the Danevirke. The themes of the 18th Viking Congress are: 1. Catalysts and change in the Viking Age As a historical period, the Viking Age is marked out as a watershed for profound cultural and social changes in northern societies: from the spread of Christianity to urbanisation and political centralisation. Exploring the causes for these changes is a core theme of Viking Studies. -

Knut Hjalmar Stolpe's Works in Peru (1884) Ellen F

Andean Past Volume 8 Article 13 2007 Bringing Ethnography Home: Knut Hjalmar Stolpe's Works in Peru (1884) Ellen F. Steinberg [email protected] Jack H. Prost University of Illinois, Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Steinberg, Ellen F. and Prost, Jack H. (2007) "Bringing Ethnography Home: Knut Hjalmar Stolpe's Works in Peru (1884)," Andean Past: Vol. 8 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol8/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRINGING ETHNOGRAPHY HOME: KNUT HJALMAR STOLPE’S WORK IN PERU (1884) Ellen FitzSimmons Steinberg Jack H. Prost University of Illinois at Chicago INTRODUCTION Stübel. Their intent was to document the tombs before the Necropolis was totally destroyed. The Ancón, on Peru’s central coast, is one of the results of their 1875 excavation were originally most explored, excavated, and plundered sites published between 1880 and 1887 in 15 volumes in that country. Located approximately 32 km titled Das Todtenfeld von Ancon in Peru, repub- north of Lima, the small fishing village has been lished in English as The Necropolis of Ancon in a seaside resort for more than one hundred years Peru . The next large scientific excavation at (Figure 1). Its real fame does not reside in its the site was performed by George Amos Dorsey sandy beaches but rather in its huge graveyard. -

Agents of Death: Reassessing Social Agency and Gendered Narratives of Human Sacrifice in the Viking Age

Agents of Death: Reassessing Social Agency and Gendered Narratives of Human Sacrifice in the Viking Age Marianne Moen & Matthew J. Walsh This article seeks to approach the famous tenth-century account of the burial of a chieftain of the Rus, narrated by the Arab traveller Ibn Fadlan, in a new light. Placing focus on how gendered expectations have coloured the interpretation and subsequent archaeological use of this source, we argue that a new focus on the social agency of some of the central actors can open up alternative interpretations. Viewing the source in light of theories of human sacrifice in the Viking Age, we examine the promotion of culturally appropriate gendered roles, where women are often depicted as victims of male violence. In light of recent trends in theoretical approaches where gender is foregrounded, we perceive that a new focus on agency in such narratives can renew and rejuvenate important debates. Introduction Rus on the Volga, from a feminist perspective rooted in intersectional theory and concerns with agency While recognizing gender as a culturally significant and active versus passive voices. We present a number and at times socially regulating principle in Viking of cases to support the potential for female agency in Age society (see, for example, Arwill-Nordbladh relation to funerary traditions, specifically related to 1998; Dommasnes [1991] 1998;Jesch1991;Moen sacrificial practices. Significantly, though we have situ- 2011; 2019a; Stalsberg 2001), we simultaneously high- ated this discussion in Viking Age scholarship, we light the dangers inherent in transferring underlying believe the themes of gendered biases in ascribing modern gendered ideologies on to the past. -

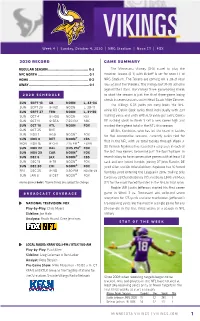

VIKINGS 2020 Vikings

VIKINGS 2020 vikings Week 4 | Sunday, October 4, 2020 | NRG Stadium | Noon CT | FOX 2020 record game summary REGULAR SEASON......................................... 0-3 The Minnesota Vikings (0-3) travel to play the NFC NORTH ....................................................0-1 Houston Texans (0-3) with kickoff is set for noon CT at HOME ............................................................ 0-2 NRG Stadium. The Texans are coming off a 28-21 road AWAY .............................................................0-1 loss against the Steelers. The Vikings lost 31-30 at home against the Titans. The Vikings three-game losing streak 2020 schedule to start the season is just the third three-game losing streak in seven seasons under Head Coach Mike Zimmer. sun sept 13 gb noon l, 43-34 The Vikings 6.03 yards per carry leads the NFL, sun sept 20 @ ind noon l, 28-11 sun sept 27 ten noon l, 31-30 while RB Dalvin Cook ranks third individually with 294 sun oct 4 @ hou noon fox rushing yards and sixth with 6.13 yards per carry. Cook’s sun oct 11 @ sea 7:20 pm nbc 181 rushing yards in Week 3 set a new career high and sun oct 18 atl noon fox marked the highest total in the NFL this season. sun oct 25 bye LB Eric Kendricks, who has led the team in tackles sun nov 1 @gb noon* fox for five consecutive seasons, currently ranks tied for sun nov 8 det noon* cbs first in the NFL with 33 total tackles through Week 3. mon nov 16 @ chi 7:15 pm* espn sun nov 22 dal 3:25 pm* fox DE Yannick Ngakoue has recorded a strip sack in each of sun nov 29 car noon* fox the last two games, becoming just the fourth player in sun dec 6 jax noon* cbs team history to have consecutive games with at least 1.0 sun dec 13 @ tb noon* fox sack and one forced fumble, joining DT John Randle, DE sun dec 20 chi noon* fox Jared Allen and DE Brian Robison. -

Uppsala. a Lot Going On. Every Day Since 1286. 4 3 3 a 7 5 Hjalmarsg 4 Ur 4 31 Bruno Liljeforsg

Destination Uppsala AB Kungsgatan 59, 753 21 Uppsala tel +46(0)18-727 48 00 [email protected] www.destinationuppsala.se 1 Uppsala Cathedral 6 Uppsala Castle 11 Old Uppsala (Uppsala domkyrka) Scandina- (Uppsala slott) The castle (Gamla Uppsala) Old Upp- via’s biggest and tallest church. was built in the 1540s, sala is one of Scandinavia’s As long as it is tall, at 118.7 and has a dramatic history. most important historic areas, m, the church is the seat of Many key events in Swedish with three royal burial sites the archbishop and was built history have been played out dating from the 6th century. between 1270 and 1435. It here. Fredens Hus (House Gamla Uppsala museum offers contains the shrine of Eric IX a fascinating journey through of Sweden (Eric the Holy) and of Peace) is here, with an a Baroque pulpit. The graves exhibition about the former time. From 6th-century pagan of Kings Gustavus Vasa and UN Secretary General Dag kingdoms to the introduction of Johan III, Linnaeus, Olof Rudbeck, Nathan Söderblom and Hammarskjöld and his achievements. The castle also Christianity. This marked the end of the Viking Age, and the others are here. The Skattkammaren (Treasury Museum) in houses the Uppsala Art Museum, with its contemporary start of construction of the old cathedral in the 12th century. the North Tower has a world-class collection of textiles. art exhibitions and Uppsala University’s art collection. Disagården is a museum of Uppland’s agricultural heritage. www.uppsaladomkyrka.se www.fredenshus.se, www.uppsala.se/konstmuseum www.raa.se/gamlauppsala 2 Uppsala University 7 Botanical Gardens 12 Fyrishov (Uppsala universitet) Founded (Botaniska trädgården) Laid Fyrishov is Sweden’s busiest in 1477, Uppsala Univer- out as royal gardens in the arena, and its fifth most sity is the oldest university in mid-17th century, to designs popular attraction. -

Full Issue Vol. 2 No. 4

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 2 | Number 4 Article 1 12-1-1982 Full Issue Vol. 2 No. 4 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1982) "Full Issue Vol. 2 No. 4," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 2 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol2/iss4/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Swedish American Genea o ist A journal devoted to Swedish American biography, genealogy and personal history CONTENTS The Emigrant Register of Karlstad 145 Swedish American Directories 150 Norwegian Sailor Last Survivor 160 Norwegian and Swedish Local Histories 161 An Early Rockford Swede 171 Swedish American By-names 173 Literature 177 Ancestor Tables 180 Genealogical Queries 183 Index of Personal Names 187 Index of Place Names 205 Index of Ships' Names 212 Vol. II December 1982 No. 4 I . Swedish Americanij Genealogist ~ Copyright © I 982 S1tiedish Amerh·an Geneal,,gtst P. 0 . Box 2186 Winte r Park. FL 32790 !I SSN 0275-9314 ) Editor and P ub lisher Nils Will ia m Olsson. Ph.D .. F.A.S.G. Contributing Editors Glen E. Brolardcr. Augustana Coll ege . Rock Island. IL: Sten Carls,on. Ph.D .. Uppsala Uni versit y. Uppsala . Sweden: Carl-Erik Johans,on. Brigham Young Univ ersity.J>rovo. UT: He nn e Sol Ib e . -

Situne Dei Årsskrift För Sigtunaforskning Och Historisk Arkeologi

Situne Dei Årsskrift för Sigtunaforskning och historisk arkeologi 2018 Redaktion: Anders Söderberg Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson Anna Kjellström Magnus Källström Cecilia Ljung Johan Runer Utgiven av Sigtuna Museum SITUNE DEI 2018 Viking traces – artistic tradition of the Viking Age in applied art of pre-Mongolian Novgorod Nadezhda N. Tochilova The Novgorod archaeological collection of wooden items includes a significant amount of pieces of decorative art. Many of these were featured in the fundamental work of B.A. Kolchin Novgorod Antiquities. The Carved Wood (Kolchin 1971). This work is, perhaps, the one generalizing study capable of providing a full picture of the art of carved wood of Ancient Novgorod. Studying the archaeological collec- tions of Ancient Novgorod, one’s attention is drawn to a number of wooden (and bone) objects, the art design of which distinctly differs from the general conceptions of ancient Russian art. The most striking examples of such works of applied art will be discussed in this article. The processes of interaction between the two cultures are well researched and presented in the works of a group of Swedish archaeologists, whose work showed the complex bonds of interaction between Sweden and Russia, reflected in a number of aspects of material culture (Arbman 1960; Jansson 1996; Fransson et al (eds.) 2007; Hedenstierna- Jonson 2009). Moreover, in art history literature, a few individ- ual works of applied art refer to the context of the spread of Viking art (Roesdahl & Wilson eds 1992; Graham-Campbell 2013), but not to the interrelation, as a definite branch of Scandinavian art, in Eastern Europe. If we apply this focus to Russian historiography, then the problem of studying archaeological objects of applied art is comparatively small, and what is important to note is that all of these studies also have an archaeological direction (Kolchin 1971; Bocharov 1983). -

Systems of Settlement Hierarchy

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Viking and Medieval Norse Studies Systems of Settlement Hierarchy A study of Husby, Central Places, and Settlement in the Mälaren Region from an Archaeological Perspective. Ritgerð til MA-prófs í Viking and Medieval Norse Studies Karl Troxell Kt.: 050994-4229 Leiðbeinandi: Orri Vésteinsson June 2019 Abstract The study of the settlement landscape of Late Iron Age, Viking Age, and Medieval Scandinavia has often focused on questions concerning the development of socio-political organization and its effect on the regional organization of settlement. In the Mälaren region in central Sweden scholars have relied on theoretical models of social and settlement hierarchy developed over nearly a century of discourse. The framework for these models was initially built on sparse literary, historical, and linguistic evidence, with archaeological material only being considered more systematically in recent decades, and then only in a secondary capacity. These considerations only being made to shed light on the existing theoretical framework. No general examination of the archaeological material has taken place to corroborate these models of settlement hierarchy based purely on an archaeological perspective. This thesis reviews the models of settlement hierarchy and social organization proposed for the Mälaren region in the Late Iron Age through Medieval Period and examines how they hold up in the face of the available archaeological evidence. It finds that while much more systematic archaeological research is necessary, the available evidence calls for a serious restructuring of these theoretical frameworks. i Ágrip Rannsóknir á landsháttum síðari hluta járnaldar, víkingaaldar og miðalda á Norðurlöndum hafa að stórum hluta miðað að því að varpa ljósi á álitamál um þróun valdakerfa og um áhrif þeirra á skipulag byggðar.