6. Coral Reefs of the U.S. Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SA Wioresearchcompendium.Pdf

Compiling authors Dr Angus Paterson Prof. Juliet Hermes Dr Tommy Bornman Tracy Klarenbeek Dr Gilbert Siko Rose Palmer Report design: Rose Palmer Contributing authors Prof. Janine Adams Ms Maryke Musson Prof. Isabelle Ansorge Mr Mduduzi Mzimela Dr Björn Backeberg Mr Ashley Naidoo Prof. Paulette Bloomer Dr Larry Oellermann Dr Thomas Bornman Ryan Palmer Dr Hayley Cawthra Dr Angus Paterson Geremy Cliff Dr Brilliant Petja Prof. Rosemary Dorrington Nicole du Plessis Dr Thembinkosi Steven Dlaza Dr Anthony Ribbink Prof. Ken Findlay Prof. Chris Reason Prof. William Froneman Prof. Michael Roberts Dr Enrico Gennari Prof. Mathieu Rouault Dr Issufo Halo Prof. Ursula Scharler Dr. Jean Harris Dr Gilbert Siko Prof. Juliet Hermes Dr Kerry Sink Dr Jenny Huggett Dr Gavin Snow Tracy Klarenbeek Johan Stander Prof. Mandy Lombard Dr Neville Sweijd Neil Malan Prof. Peter Teske Benita Maritz Dr Niall Vine Meaghen McCord Prof. Sophie von der Heydem Tammy Morris SA RESEARCH IN THE WIO ContEnts INDEX of rEsEarCh topiCs ‑ 2 introDuCtion ‑ 3 thE WEstErn inDian oCEan ‑ 4 rEsEarCh ActivitiEs ‑ 6 govErnmEnt DEpartmEnts ‑ 7 Department of Science & Technology (DST) Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries (DAFF) sCiEnCE CounCils & rEsEarCh institutions ‑ 13 National Research Foundation (NRF) Council for Geoscience (CGS) Council for Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) Institute for Maritime Technology (IMT) KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board (KZNSB) South African Environmental Observation Network (SAEON) Egagasini node South African -

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Review and Discussion February 19, 2020 IJ Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission This is a review and discussion of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary’s (FKNMS) Restoration Blueprint, the FWC’s role in managing the fisheries resources within the FKNMS, proposed regulatory actions, and next steps. Division: Marine Fisheries Management Authors: Jessica McCawley, John Hunt, Martha Guyas, and CJ Sweetman Contact Phone Number: 850-487-0554 Report date: February 17, 2020 Unless otherwise noted, images throughout the presentation are by FWC or Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. FKNMS Process Reminder • Oct. and Dec. - FKNMS discussions • Jan. - FWC staff meetings with diverse stakeholder organizations • Today - Look at all relevant aspects of plan and consider FWC's proposed response • April - FWC comments due • Summer 2020 - FWC begin rulemaking process for state waters As a management partner in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), FWC has been engaged in review of the Restoration Blueprint (Draft Environmental Impact Statement, DEIS) over the past several months. In October and December, the Commission discussed the FKNMS Restoration Blueprint. In January, FWC staff met with a variety of stakeholders to better understand their comments on particular issues addressed within the DEIS. Today, the presentation will cover all relevant aspects of the plan and staff recommendations based on a review of the science and stakeholder comments, which will be outlined in the next two slides. FWC requested and has been granted an extension for submitting agency comments to the FKNMS until April. Following the Commission’s response to the FKNMS, FWC will consider rulemaking for fisheries management items state waters. -

FAU Institutional Repository

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute Notice: ©2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. This is the author’s version of a work accepted for publication by Elsevier. Changes resulting from the publishing process, including peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting and other quality control mechanisms, may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. The definitive version has been published at http://www.elsevier.com/locate/csr and may be cited as Lee, Thomas N., Ned Smith (2002) Volume transport variability through the Florida Keys tidal Channels, Continental Shelf Research 22(9):1361–1377 doi:10.1016/S0278‐4343(02)00003‐1 Continental Shelf Research 22 (2002) 1361–1377 Volume transport variability through the Florida Keys tidal channels Thomas N. Leea,*, Ned Smithb a Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, FL 33149, USA b Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, 5600 US Highway 1, North, Ft. Pierce, FL 34946, USA Received 28 February 2001; received in revised form 13 July 2001; accepted 18 September 2001 Abstract Shipboard measurements of volume transports through the passages of the middle Florida Keys are used together with time series of moored transports, cross-Key sea level slopes and local wind records to investigate the mechanisms controllingtransport variability. Predicted tidal transport amplitudes rangedfrom 76000 m3/s in LongKey Channel to 71500 m3/s in Channel 2. Subtidal transport variations are primarily due to local wind driven cross-Key sea level slopes. -

Key West & the Lower Keys

© Lonely Planet Publications Key West & the Lower Keys in the ’60s to lend the island a South 40 NEWFOUND HARBOR Pacific look when it was used as the set- ting for the movie PT-109. Location: 0.5 nautical miles (1km) A series of mooring buoys are in place south of Newfound Harbor Keys along the west side of the reef, and day Depth Range: Surface-18ft (5m) marker 50 lies to the south. The top of Access: Boat the reef is very shallow, rising almost Expertise Rating: Novice to the surface in two places. Maximum depth is about 8ft (2.4m) on the land- -169 ward side and 18ft (5m) on the seaward side. Soft corals dominate much of the Closer to shore than most other reefs, reef, but boulder-like accumulations this sanctuary preservation area is a of calcium carbonate from hard corals good alternative when weather pre- form the basic structure. vents diving at nearby Looe Key. Just Fishermen frequented the reef until northwest is low-lying Little Palm Is- the summer of 1997 when the SPA went land, now home to an exclusive resort. into effect, and the resident fish popula- The namesake palm trees were planted tion has been steadily increasing ever Key West & Lower Keys Snipe Keys Mud Keys 24º40’N 81º55’W 81º50’W 81º45’W 81º40’W Waltz Key Basin Lower Harbor Bluefish Channel Keys Bay Keys Northwest Channel Calda Bank Cottrell Key Great White Heron National Wildlife Refuge Big Coppitt Key Fleming Key 24º35’N Lower Keys Big Mullet Key Medical Center 1 Stock Island Boca Chica Key Mule Key Key West Naval Air Station Duval St Archer Key Truman Ave Flagler -

An Environmental Assessment of the John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park and the Key Largo Coral Reef Marine Sanctuary (Unpublished 1983 Report)

An environmental assessment of the John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park and the Key Largo Coral Reef Marine Sanctuary (Unpublished 1983 Report) Item Type monograph Authors Voss, Gilbert L.; Voss, Nancy A.; Cantillo, Andriana Y.; Bello, Maria J. Publisher NOAA/National Ocean Service/National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science Download date 07/10/2021 01:47:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/19992 NOAA/University of Miami Joint Publication NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS CCMA 161 NOAA LISD Current References 2002-6 University of Miami RSMAS TR 2002-03 Coastal and Estuarine Data Archaeology and Rescue Program AN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF THE JOHN PENNEKAMP CORAL REEF STATE PARK AND THE KEY LARGO CORAL REEF MARINE SANCTUARY (Unpublished 1983 Report) November 2002 US Department of Commerce University of Miami National Oceanic and Atmospheric Rosenstiel School of Marine and Administration Atmospheric Science Silver Spring, MD Miami, FL a NOAA/University of Miami Joint Publication NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS CCMA 161 NOAA LISD Current References 2002-6 University of Miami RSMAS TR 2002-03 AN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF THE JOHN PENNEKAMP CORAL REEF STATE PARK AND THE KEY LARGO CORAL REEF MARINE SANCTUARY (Unpublished 1983 Report) Gilbert L. Voss Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science University of Miami Nancy A. Voss Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science University of Miami Adriana Y. Cantillo NOAA National Ocean Service Maria J. Bello NOAA Miami Regional Library (Editors, 2002) November 2002 United States National Oceanic and Department of Commerce Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Donald L. Evans Conrad C. Lautenbacher, Jr. -

Reef Explorer Guide Highlights the Underwater World ALLIGATOR of the Florida Keys, Including Unique Coral Reefs from Key Largo to OLD CANNON Key West

REEF EXPLORER The Florida Keys & Key West, "come as you are" © 2018 Monroe County Tourist Development Council. All rights reserved. MCTDU-3471 • 15K • 7/18 fla-keys.com/diving GULF OF FT. JEFFERSON NATIONAL MONUMNET MEXICO AND DRY TORTUGAS (70 MILES WEST OF KEY WEST) COTTRELL KEY YELLOW WESTERN ROCKS DRY ROCKS SAND Marathon KEY COFFIN’S ROCK PATCH KEY EASTERN BIG PINE KEY & THE LOWER KEYS DRY ROCKS DELTA WESTERN SOMBRERO SHOALS SAMBOS AMERICAN PORKFISH SHOALS KISSING HERMAN’S GRUNTS LOOE KEY HOLE SAMANTHA’S NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY OUTER REEF CARYSFORT ELBOW DRY ROCKS CHRIST GRECIAN CHRISTOF THE ROCKS ABYSS OF THE KEY ABYSSA LARGO (ARTIFICIAL REEF) How it works FRENCH How it works PICKLES Congratulations! You are on your way to becoming a Reef Explorer — enjoying at least one of the unique diving ISLAMORADA HEN & CONCH CHICKENS REEF MOLASSES and snorkeling experiences in each region of the Florida Keys: LITTLE SPANISH CONCH Key Largo, Islamorada, Marathon, Big Pine Key & The Lower Keys PLATE FLEET and Key West. DAVIS CROCKER REEF REEF/WALL Beginners and experienced divers alike can become a Reef Explorer. This Reef Explorer Guide highlights the underwater world ALLIGATOR of the Florida Keys, including unique coral reefs from Key Largo to OLD CANNON Key West. To participate, pursue validation from any dive or snorkel PORKFISH HORSESHOE operator in each of the five regions. Upon completion of your last reef ATLANTIC exploration, email us at [email protected] to receive an access OCEAN code for a personalized Keys Reef Explorer poster with your name on it. -

Florida Keys Lobster Regulations

FACTS TO KNOW BEFORE YOU GO. Additional rules and measuring information found in Rules For All Seasons & Measuring Lobster sections of this brochure. FLORIDA KEYS AREAS/ZONES CLOSED TO HARVEST OF SPINY LOBSTER LOBSTER REGULATIONS FLORIDA KEYS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY JOHN PENNEKAMP Includes Mini Sport Season CLOSED ZONES (YEAR-ROUND) CORAL REEF STATE (MARKED BY 30” YELLOW BOUNDARY BUOY) PARK (JPCRSP) Sanctuary Preservation Areas Ecological Reserves Special-use Research JPCRSP is Closed (SPAs) Western Sambo, Only Areas (No entry) for Sport Season Carysfort Reef, The Elbow, Tortugas Ecological Conch Reef, All of JPCRSP is closed Key Largo Dry Rocks, Grecian Reserve North Tennessee Reef, during the 2-day Sport Rocks, French Reef, Molasses and South Looe Key Patch Reef, Season for the harvest of Reef, Conch Reef, Davis Reef, (refer to GPS coordinates, Eastern Sambo. any lobster species. Hen and Chickens, Cheeca Rocks, not marked). Year-Round Coral Rule: Alligator Reef, Coffins Patch, No person shall harvest Sombrero Key, Newfound Harbor any lobster species from Key, Looe Key, Eastern Dry Rocks, or within any coral Rock Key, Sand Key. formation (patch reef) regardless of its proximity Other Closed Areas (Year-Round) to or exclusion from a Lobster Exclusion Zone. Everglades National Park Biscayne Bay Card Sound Spiny City of Layton Lobster Sanctuary JPCRSP Lobster Dry Tortugas National Park Artificial Habitat Exclusion Zones: Biscayne National Park Coral Reef in State Waters Closed year-round. Protection Areas Marked by Orange/White Spar buoys, found at: Spanish and Slipper Lobster Closed Areas Turtle Rocks, Basin Hills Spanish and Slipper Lobster are closed year-round North, Basin Hills East, to harvest in Key Largo and Looe Key Existing Management Areas, Basin Hills South, Higdon’s Reef, Cannon all FKNMS zones listed above in this table, Everglades Patch, Mosquito Bank KeysLobsterSeason.com & Dry Tortugas National Parks. -

Use of High Resolution Pathfinder Sst Data to Document Coral Reef Bleaching*

USE OF HIGH RESOLUTION PATHFINDER SST DATA TO DOCUMENT CORAL REEF BLEACHING* M. A. Toscano NOAA/NESDIS/ORA/ORAD Silver Spring, MD USA K. S. Casey NOAA/NESDIS/NODC Silver Spring, MD USA J. Shannon U. S. Naval Academy Annapolis, MD, USA ABSTRACT Mass coral bleaching has been observed throughout the tropical oceans immediately following periods of thermal stress, in concert with other known causes. While water temperatures monitored in situ best document the relationship of thermal stress to bleaching, most reef sites have limited to no in situ data. For such areas, high-resolution satellite-derived SSTs provide valuable time series data and quantify thermal anomalies and their timing vs. onset of bleaching. The availability of 9km NOAA/NASA Oceans Pathfinder SST data (1985-2001), an internally consistent, calibrated SST database at reef scale resolution, allows us to assess the accuracy and usefulness of satellite SST data to document past conditions in reefs. Statistical analyses of SSTs combined with available in situ temperatures from Caribbean and tropical Pacific locations indicate that 9km SSTs for specific sites, and for the 3x3 pixel means surrounding each site, are highly correlated to in situ temperatures. Biases are tied, wherever possible, to local physical causes. Pathfinder SSTs accurately represent surface field temperatures with predictable exceptions, and therefore have great potential for assessing temperature histories of remote, un-monitored reefs. 1.0 THERMAL STRESS AND CORAL REEF BLEACHING Bleaching is the loss of algal symbionts (zooxanthellae) and/or their pigments from a coral (or other symbiotic animal) host, and occurs in response to environmental stressors which vary regionally and seasonally, and which may act singly or synergistically (Fitt et al. -

FKNMS Accomplishments FY2009

SOUTHEAST REGIONAL PRIORITIES Science Staff Provide Support for Southeast Region The Southeast Region of the NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries provides direct support to the sanctuary sites through its 2009 ACCOMPLISHMENTS regional science coordinators, who are active in a wide range of projects within NOAA as well as with other agencies and academia. In 2009, the region’s science coordinator worked to support the science program at Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, in addition to several national initiatives such as the Southeast Atlantic and Caribbean Regional Team. The region’s associate science coordinators helped Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary prepare an environmental impact statement that will support the site’s proposed sanctuary expansion; represented the sanctuary on NOAA’s Gulf of Mexico Regional Collaboration Team; served as the co- chief scientist for the Gray’s Reef sanctuary cruise aboard the NOAA ship Nancy Foster that supported four separate research projects and involved 12 organizations and numerous volunteers; and helped lead an acoustic study of fish movement underway at Gray’s Reef. Collaborative Efforts Help Protect U.S. Coral Reefs The region has been an active part of the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force and has worked closely with NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program to help implement programs and steer the future direction of the United States’ coral reef protection efforts. The Southeast Region director chairs the land-based sources of pollution task force working group that has developed strategies for addressing water quality decline in coral reef areas of the U.S. These collaborations with the Coral Reef Task Force and with NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program are testament to the important role that our sanctuaries play in research, education and management of coral reefs and in demonstrating the success of coral reef conservation policies. -

Geology of Florida Local Abundance of Quartz Sand

28390_00_cover.qxd 1/16/09 4:03 PM Page 1 Summary of Content The geologic past of Florida is mostly out of sight with its maximum elevation at only ~105 m (in the panhandle) and much of south Florida is virtually flat. The surface of Florida is dominated by subtle shorelines from previous sea-level high-stands, karst-generated lakes, and small river drainage basins What we see are modern geologic (and biologic) environments, some that are world famous such as the Everglades, the coral reefs, and the beaches. But, where did all of this come from? Does Florida have a geologic history other than the usual mantra about having been “derived from the sea”? If so, what events of the geologic past converged to produce the Florida we see today? Toanswer these questions, this module has two objectives: (1) to provide a rapid transit through geologic time to describe the key events of Florida’s past emphasizing processes, and (2) to present the high-profile modern geologic features in Florida that have made the State a world-class destination for visitors. About the Author Albert C. Hine is the Associate Dean and Professor in the College of Marine Science at the University of South Florida. He earned his A.B. from Dartmouth College; M.S. from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; and Ph.D. from the University of South Carolina, Columbia—all in the geological sciences. Dr. Hine is a broadly-trained geological oceanographer who has addressed sedimentary geology and stratigraphy problems from the estuarine system out to the base of slope. -

What Is Coral Bleaching

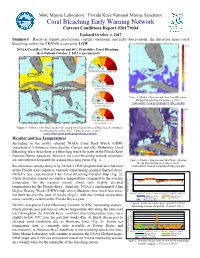

Mote Marine Laboratory / Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Coral Bleaching Early Warning Network Current Conditions Report #20171004 Updated October 4, 2017 Summary: Based on climate predictions, current conditions, and field observations, the threat for mass coral bleaching within the FKNMS is currently LOW. NOAA Coral Reef Watch Current and 60% Probability Coral Bleaching Alert Outlook October 2, 2017 (experimental) June 30, 2015 (experimental) Figure 2. NOAA’s Experimental 5km Coral Bleaching HotSpot Map for Florida October 2, 2017. coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/vs/gauges/florida_keys.php Figure 1. NOAA’s 5 km Experimental Current and 60% Probability Coral Bleaching Alert Outlook Areas through December, 2017. Updated October 2, 2017. coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/vs/gauges/florida_keys.php Weather and Sea Temperatures According to the newly released NOAA Coral Reef Watch (CRW) experimental 5 kilometer (km) Satellite Current and 60% Probability Coral Bleaching Alert Area, there is a bleaching watch for parts of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, however, the coral bleaching outlook conditions are currently not favorable for a mass bleaching event (Fig. 1). Figure 3. NOAA’s Experimental 5km Degree Heating Weeks Map for Florida October 2, 2017. Recent remote sensing analysis by NOAA’s CRW program indicates that most coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/vs/gauges/florida_keys.php of the Florida Keys region is currently experiencing minimal thermal stress. NOAA’s new experimental 5 km Coral Bleaching HotSpot Map (Fig. 2), 35 which illustrates current sea surface temperatures compared to the average 30 temperature for the warmest month, shows only slightly elevated temperatures for the Florida Keys. Similarly, NOAA’s experimental 5 km 25 20 Degree Heating Weeks (DHW) map, which illustrates how much heat stress Temp. -

Climate Change:Change: Whatwhat Cancan Coralcoral Reefreef Managersmanagers Dodo Toto Addressaddress Coralcoral Bleaching?Bleaching?

ClimateClimate Change:Change: WhatWhat CanCan CoralCoral ReefReef ManagersManagers DoDo ToTo AddressAddress CoralCoral Bleaching?Bleaching? U.S. Coral Reef Task Force – 16 “A Reef Manager’s Guide to Coral Bleaching” October 23-28, 2006 St. Thomas, USVI Billy D. Causey, Ph.D. Regional Director Southeast Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Region Reef Manager’s Guide • Need for management response • Guide Offers a Framework • Local Management Actions • Examples of Local Actions Possible Management Actions • Utilize in situ and remote sensing observations to predict and plan for bleaching events • Communicate observations to the public, scientists and other managers – engage the public • Target research at specific questions • Apply the concept of Reef Resiliency in planning Possible Management Actions • Utilize in situ and remote sensing observations to predict and plan for bleaching events • Communicate observations to the public, scientists and other managers • Target research at specific questions • Apply the concept of Reef Resiliency in planning Importance of in situ observations In predicting coral bleaching events • Doldrum conditions for extended periods • Low Cloud cover • Minimal water circulation • Elevated Sea Surface temperatures • Has increased the public’s confidence in science and government In-Situ Monitoring NDBC/FIO/FKNMS/SeaKeys ö Stations Molasses$T Reef ö N Dry$T Tortugas Sombrero$T Reef ö W E Sand Key$T Reef S Thermograph Locations in the FKNMS • 32 meters to record water temperature • 7 CMAN Stations along reef