1 Excerpt from Thomas Mallon's “Wag the Dog: the Making of Richard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion Film File Title Listing

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-001 "On Guard for America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #1" (1950) One of a series of six: On Guard for America", TV Campaign spots. Features Richard M. Nixon speaking from his office" Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. Cross Reference: MVF 47 (two versions: 15 min and 30 min);. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-002 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #2" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-003 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #3" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available Monday, August 06, 2018 Page 1 of 202 Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-004 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #4" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. -

AHR Forum the Rise and Fall of an International Counterculture, 1960–1975

AHR Forum The Rise and Fall of an International Counterculture, 1960–1975 JEREMI SURI IN THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE—BETTY FRIEDAN’S 1963 attack on domesticity—the au- thor describes how she “gradually, without seeing it clearly for quite a while . came to realize that something is very wrong with the way American women are trying to live their lives today.”1 Despite the outward appearance of wealth and contentment, Friedan argued that the Cold War was killing happiness. Women, in particular, faced strong public pressures to conform with a family image that emphasized a finely manicured suburban home, pampered children, and an ever-present “housewife her- oine.”2 This was the asserted core of the good American life. This was the cradle of freedom. This was, in the words of Adlai Stevenson, the “assignment” for “wives and mothers”: “Western marriage and motherhood are yet another instance of the emer- gence of individual freedom in our Western society. Their basis is the recognition in women as well as men of the primacy of personality and individuality.”3 Friedan disagreed, and she was not alone. Surveys, interviews, and observations revealed that countless women suffered from a problem that had no name within the standard lexicon of society at the time. They had achieved the “good life,” and yet they felt unfulfilled. Friedan quoted one particularly articulate young mother: I’ve tried everything women are supposed to do—hobbies, gardening, pickling, canning, being very social with my neighbors, joining committees, running PTA teas. I can do it all, and I like it, but it doesn’t leave you anything to think about—any feeling of who you are. -

Richard Nixon's ''Checkers'' Speech, 1952

Richard Nixon's ''Checkers'' Speech, 1952 September 23, 1952 My fellow Americans: I come before you tonight as a candidate for the Vice Presidency and as a man whose honesty and integrity have been questioned. The usual political thing to do when charges are made against you is to either ignore them or to deny them without giving details. I believe we've had enough of that in the United States, particularly with the present Administration in Washington D.C. To me the office of the Vice Presidency of the United States is a great office, and I feel that the people have got to have confidence in the integrity of the men who run for that office and who might obtain it. I have a theory, too, that the best and only answer to a smear or to an honest misunderstanding of the facts is to tell the truth. And that's why I'm here tonight. I want to tell you my side of the case. I am sure that you have read the charge and you've heard it that I, Senator Nixon, took $18,000 from a group of my supporters. Now, was that wrong? And let me say that it was wrong-I'm saying, incidentally, that it was wrong and not just illegal. Because it isn't a question of whether it was legal or illegal, that isn't enough. The question is, was it morally wrong? I say that it was morally wrong if any of that $18,000 went to Senator Nixon for my personal use. -

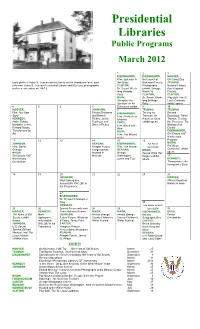

Presidential Libraries Public Programs

Presidential Libraries Public Programs March 2012 1 2 3 EISENHOWER, EISENHOWER, HOOVER, Film: Splendor in Art Council of Girl Scout Day Early photo of Harry S. Truman and his family on the Grandview farm, date the Grass Dickinson County TRUMAN, unknown. Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, photographic CLINTON, Photography National History archives, accession no. 84-13. Dr. Seuss’ Week- Exhibit, through Day Regional long Birthday March 16 Contest Party CLINTON, CLINTON, BUSH, Dr. Seuss’ Week- Play Ball! The St. Reception for long Birthday Louis Cardinals Spotlight on Art Party exhibit opens 4 5 6 7 Educators exhibit 9 10 HOOVER, JOHNSON, 8 TRUMAN, TRUMAN, Film: Her Own Sharon Robinson EISENHOWER, Tracing the Second Story and Branch Film: Pocketful of Trumans: An Saturdays, Talkin’ KENNEDY, Rickey, Jackie Miracles American Story Truman, Tracing Andre Dubus, Robinson and FORD, exhibit opens the Tru-mans: The Marianne Leone, Branch Rickey Film, Black and Making of an Richard Russo, Blue Exhibit Transformed by EISENHOWER, BUSH, th Art Film, The Wizard Girl Scouts 100 of Oz Anniversary 11 12 13 14 15 16 Program JOHNSON, REAGAN, EISENHOWER, Pat Nixon NIXON, Pat Nixon Film, Game Reagan Forum, Film: The Hustler born 1912 Centennial exhibit Change Congressman REAGAN, NIXON, opens NIXON, Howard P. George People Were Her th Girl Scouts 100 McKeon Washington Project exhibit 17 Anniversary Lunch and Tour opens KENNEDY, Celebration Themselves – An Immigrant’s Story 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 JOHNSON, HOOVER, Mark Updegrove, African American Indomitable Will: LBJ in History in Iowa the Presidency 27 EISENHOWER, Dr. Wendell Christopher King 30 KENNEDY, Lou Henry Hoover 25 26 Special Forum with Irish 28 29 born 1874 31 HOOVER, KENNEDY, Tenor Anthony Kearns NIXON, NIXON, EISENHOWER, BUSH, 100 Years of Girl Mark JOHNSON, Annual Orange Annual Orange Kansas Easter Scouts exhibit Updegrove, Future Forum, Whatever County Children’s County Children’s Geographic Bee Celebration closes Indomitable It Takes: Texas Educ. -

Oliver Stone's Nixon: Politics on the Edge of Darkness IAN SCOTT

Oliver Stone's Nixon: Politics on the Edge of Darkness IAN SCOTT In the introduction to his controversial book, The Ends of Power , former White House Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman describes Watergate as being an expression «of the dark side of President Nixon» 1. Later in the book Haldeman cites former Special Counsel Charles Colson as a key man who «encouraged the dark impulses in Nixon's mind» 2. Stephen Ambrose has written that Nixon «never abandoned his black impulses to lash out at the world...», while Henry Kissinger offered the view that «the thoughtful analytical side of Nixon was most in evidence during crises, while periods of calm seemed to unleash the darker passions of his nature» 3. Christopher Wilkinson -talking directly about Oliver Stone's film-has focused on the movie's analogy of a «beast» that «also became a metaphor for the dark side of Nixon himself» 4. Wherever you look in the vast array of literature on the life and times of President Richard Nixon, as sure as you are to hear the description «Shakespearean tragedy», so the notions of dark and brooding forces are never far away, following in the shadows of the man. As many have pointed out, however, Nixon's unknown blacker side was not merely a temperamental reaction, not only a protective camouflage to deflect from the poor boy made good syndrome that he was proud about and talked a great deal of, but always remained an Achilles heel in his own mind; no the concealment of emotional energy was tied up in the fascination with life and beyond. -

Statement on the Death of Pat Nixon June 22, 1993 Statement by the Press Secretary on the President's Task Force on National H

Administration of William J. Clinton, 1993 / June 22 1157 you. You know everything already. [Laugh- ily today as we remember her many accom- ter] plishments and contributions to the Nation. NOTE: The President spoke at 12:45 p.m. in the Statement by the Press Secretary on Oval Office at the White House. The exchange the President's Task Force on portion of this item could not be verified because National Health Care Reform the tape was incomplete. June 22, 1993 Statement on the Death of Pat Nixon June 22, 1993 The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled today that the The Nation is deeply saddened today by President's Task Force on Health Care Re- the loss of former First Lady Pat Nixon. form, chaired by First Lady Hillary Rodham Patricia Ryan Nixon was a quiet pioneer Clinton, was not subject to the Federal Advi- whose concern for family and country will sory Committee Act. The Court of Appeals leave a lasting mark on history. Mrs. Nixon decision confirms that the task force oper- personified a deep reverence for the cher- ated in full compliance with the law. ished American traditions of community In reversing the United States district service, voluntarism, and personal respon- court on this issue, the court of appeals held sibility to one another. that Mrs. Clinton is a ``full-time officer or As First Lady, she was indeed a lady of employee of the Government'' for purposes ``firsts.'' She was the first First Lady to rep- resent the President of the United States on of the advisory committee act. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS January 15, 1969 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS KENTUCKY's Looth ARMY RESERVE Now Stationed at Bowman Field-Traces Its MRS

934 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS January 15, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS KENTUCKY'S lOOTH ARMY RESERVE now stationed at Bowman Field-traces its MRS. NIXON TRAINING DIVISION CELEBRATES lineage back to the closing days of World 50TH ANNIVERSARY War I. The lOOth Division was formed on paper July 23, 1918. In October 1918, at Camp HON. CLIFFORD P. CASE Bowie, Texas, the first Centurymen were OF NEW JERSEY HON. WILLIAM 0. COWGER chosen and organization of the Headquarters IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES OF KENTUCKY & Headquarters Company began. But before Wednesday, January 15, 1969 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the unit was fully formed, the Armistice came, and on November 30th the lOOth was Mr. CASE. Mrs. Vera Glaser, of the Wednesday, January 15, 1969 demobilized, its hour to come in another North American Newspaper Alliance, has Mr. COWGER. Mr. Speaker, during war. In 1921, the Division was reconstituted as written a most interesting series of arti the congressional recess the largest a unit in the Organized Reserves, with head cles on Mrs. Richard Nixon, which I ask Army Reserve unit in the Bluegrass quarters in Wheeling. Its units included the to be printed in the RECORD. These arti State, the lOOth Division-Training 400th Infantry Regiment in Louisville, or cles were carried by many of the major celebrated the 50th anniversary of its ganized in 1922. dailies throughout the country, among Louisville headquarters which was On August 1, 1942, at Fort Jackson, S.C., others, by the Newark Star-Ledger in formed in the closing days of World the lOOth was reborn for combat and began my own State, the Baltimore Sun, Detroit War!. -

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ ◦ [email protected]

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] NAVAL PHOTOGRAPHIC CENTER FILM COLLECTION ● NPC-1211-091-69 Place holder for missing P number rolls (no date) Original Format: 16mm film Film. Cross Reference: 074-075. Reference copy may be created upon request. ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-0544 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969, Washington, D.C.) Original Format: 16mm film Film. Reference copy may be created upon request. ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-0981 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969, Washington, D.C.) Original Format: 16mm film Film. DVD reference copy available ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-1075 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969) Original Format: 16mm film Film. DVD reference copy available ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-1078 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969, Washington, D.C.) Original Format: 16mm film Film. Reference copy may be created upon request. Monday, August 06, 2018 Page 1 of 150 Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] NAVAL PHOTOGRAPHIC CENTER FILM COLLECTION ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-1951 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969, Washington, D.C.) Original Format: 16mm film Film. DVD reference copy available ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-2816 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969, Washington, D.C.) Keywords: Melvin Laird Original Format: 16mm film Film. Cross Reference: 074-075. DVD reference copy available ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-2877 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969, Washington, D.C.) Original Format: 16mm film Film. DVD reference copy available ● NPC-1211-091-69-P-5168 1969 Inauguration (1/20/1969, Washington, D.C.) Original Format: 16mm film Film. -

Herbert G. Klein Papers 0345

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3779s10w Online items available Finding Aid for the Herbert G. Klein papers 0345 Sue Luftschein USC Libraries Special Collections 2010 Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California 90089-0189 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.usc.edu/locations/special-collections Finding Aid for the Herbert G. 03451064 1 Klein papers 0345 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Title: Herbert G. Klein papers creator: Harris & Ewing creator: Allen, William C. creator: Fisk, Walter W. creator: Haberman, Irving creator: Atkins, Oliver F. creator: Zeni Photography creator: Hawkins, J. Allen creator: Jarvis, Roy creator: Parker, Buffy creator: Bonnay, Charles creator: Bachrach, Fabian creator: Rothschild Photo creator: Smith, Merrett T. creator: Sullivan, Ed creator: Klein, Herbert G. (Herbert George) creator: Lew, Mervyn creator: O'Neill, Dev creator: Mattox, Warren Identifier/Call Number: 0345 Identifier/Call Number: 1064 Physical Description: 293.66 Linear Feet257 boxes, 1 flat file drawer Date: 15th-17th centuries, 1932-2009 (bulk 1960-1973) Abstract: The Herbert G. Klein papers contain detailed records of the day to day activities of Herbert G. Klein, University of Southern California alumnus and trustee, journalist, editor and first White House Director of Communications. Included are records from all phases of Klein's long career: his early career as a journalist with Copley Newspapers in Alhambra and San Diego; his work with Richard Nixon, beginning with the Vice Presidential campaign of 1956; and his subsequent career as a media professional and author. Organization The collection is organized into eight series: 1. Richard Nixon's early political career 2. -

Nixon in China Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards

JOHNADAMS Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Lesson Plans . .9 Synopsis . .36 John Adams – a biography .................................38 Background Notes . .40 World Events in 1987 ....................................44 History of Opera ........................................45 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .56 The Standard Repertory ...................................60 Elements of Opera .......................................61 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................65 GIACOMO PUCCINI NOVEMBER 6 – 14, 2004 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................71 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .74 GAETANO DONIZETTI Evaluation . .77 MARCH 5 – 13, 2005 Acknowledgements . .78 GEORGES BIZET APRIL 16 – 24, 2005 JOHN ADAMS mnopera.org MAY 14 – 22, 2005 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. As this project is new, your feedback is imperative. Comments and ideas from you – the educators who actually use it – will help shape the content for future boxes. -

Check out the New Selection of Biographies at the Library. Academy

Check out the new selection of biographies at the library. Academy Award winner Shirley MacLainehas written her 12th book titled I'm Over All That, and Other Confessions. Shirley, being in the entertainment business, has worked with some truly great actors and actresses throughout her career. People like Elizabeth Taylor, Jack Lemon, Alfred Hitchcock, and many more. Her movie and stage performances span more than a decade. Now she just wants to live her own life quietly. Shirley's not interested in the latest fashions, being on someone's A list, or getting ready for the red carpet. She likes going to the movies, having a good meal, and loves attending notable charity events. Find out the latest scoop about Shirley in this witty and entertaining book. Soap opera star, Susan Lucci's, television history character, Erica Kane on All My Childrenhas earned her the title as “Leading Lady of Daytime.” Erica is a villain in some episodes, and a damsel in distress in others, and those who watch the show love her or love to hate her. Lucci's latest memoir titled All My Lifetalks about her childhood, her husband's cancer, her career in television and much more. Pick this one up today. Ashley Judd,the other daughter of singing sensation Naomi Judd, has written a memoir of her life titled All That Is Bitter and Sweet. At one time Ashley had a successful career in Hollywood. She suddenly walked away from it all to become a humanitarian and advocate for those who are neglected, and suffering in Southeast Asia. -

President Nixon's Favorite Mayor: Richard G. Lugar's Mayoral Years

President Nixon’s Favorite Mayor: Richard G. Lugar’s Mayoral Years and Rise to National Politics By Kelsey Green University of Indianapolis Undergraduate History Program, Spring 2021 Undergraduate Status: Senior [email protected] Green 1 A WARM HOOSIER WELCOME On February 5th, 1970 at 12:20 in the afternoon, President Richard Milhous Nixon landed in Indianapolis, Indiana. Nixon was accompanied in Air Force One by First Lady Pat Nixon, Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Secretary George W. Romney, and his top aides H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman among others. His other advisor, Daniel P. Moynihan, would rendezvous with the presidential entourage later that day.i Awaiting his arrival on the tarmac, Governor Edgar Whitcomb and Mayor Richard Lugar led the local reception committee. Donning winter overcoats, the president and Mayor Lugar are seen cordially greeting one another in a striking black and white photo. On the left, the young Lugar extends his hand to a much older and harried Nixon. Both men are smiling and framed by a large camera and microphone to record this historic moment.ii Nixon would later remark that he was received with a “warm Hoosier welcome on a rather cold day.”iii This was the first time Nixon had visited Indianapolis as president and was his first publicized meeting with Mayor Lugar, the up-and-coming politician who now represented the revitalized Republican Party in Indianapolis. After exchanging pleasantries and traveling to Indianapolis City Hall, Nixon and Lugar spoke to the crowd of approximately 1,000 Hoosiers before