Mourning in Shakespeare: Different Aspects of Surviving Death CHAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Libraries12007 Libraries

Playing with Good and Evil: Videogames and Moral Philosophy by Peter E. Rauch B.A. Liberal Arts and Sciences Florida Atlantic University, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2007 ©2007 Peter E. Rauch. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: - Program in Comparative Media Studies May 8, 2007 Certified by: 7i7-•IHenry Jenkins Peter de Flore rofesor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, ComparativeMedia Studcl Accepted by: ,ýýdifr Jenkins Peter de Florez Profdssor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies OF TECHNOLOGY ARCHIVES LIBRARIES12007 LIBRARIES Playing with Good and Evil: Videogames and Moral Philosophy by Peter E. Rauch Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT Despite an increasingly complex academic discourse, the videogame medium lacks an agreed-upon definition. Its relationship to previous media is somewhat unclear, and the unique attributes of the medium have not yet been fully catalogued. Drawing on theory suggesting that videogames can convey ideas, I will argue that the videogame medium is capable of modeling and critiquing elements of moral philosophy in a unique manner. -

Health Sciences Library

VIDEO CATALOGUE OCTOBER 2013 Health Sciences Library Phone: (705) 523-7100 Ext 3375 Email: [email protected] WHO CAN BORROW? The following videos and audio-cassettes are available to the staff, volunteers and health care professionals at the Sudbury Regional Hospital from the Health Sciences Library. Professionals and healthcare workers in the Sudbury area can also make use of these resources by inquiring. The library makes every effort to support the educational and clinical needs of those working in related healthcare fields. LOAN PERIOD Videos and audio-cassettes are available for loan for a one week period. Mailing time will be added to the loan period to ensure a reasonable viewing time is available. RETURNING VIDEOS? Materials borrowed must be returned at the borrower’s expense. Return materials to the Health Sciences Library in person or by mail. Materials returned through the mail must be returned by registered mail – priority post or courier to ensure the safe return of these items. Please advise when materials cannot be returned on time. DAMAGED OR LOST VIDEOS? All materials damaged or lost will be replaced at the borrower’s expense. COPYRIGHT All videos and audio-cassettes are protected by Canadian Copyright Legislation. Reproduction in whole or part, by videotape, video disc or by any other means in existence or hereafter devised, conceived or invented it expressly forbidden. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PSYCHOLOGY ................................................................................. 4 APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY ...................................................................... -

Denials of Death,.Fro* Jacobean Literature to Modern Journalism

Immortal Longings and Common Lyings: Denials of Death,.fro* Jacobean Literature to Modern Journalism Robert Watson University of California, Los Angeles "To Conclude, let this ever be holden as a principall by all Christians, that how soever our death is ordinarily brought upon us by sicknesse, decay ofnature, or other inferiour meanes, yet are they all swayed and ordered not onely by a generall influence. but even by a speciall ordinance and appoint- ment of Cod."l William Sclater, I Funerall Sermon (1607) "Certainely, we were better to call twenty naturatl accidents judgements of God, then frustrate Cods purpose in any ofhis powerfull deliverances, by calling it a naturall accident, and suffer the thing to vanishso..."2 John Donne, Sermons I - Evasions of Death Putting a funeral um in the middle of one's mental landscape is something like Wallace Stevens placing a jar on that Tennessee hillside: reality seems to organize itself around that empty core, that plain but mysterious concept. In his Pulitzer-winning book The Denial of Death,Emest Becker demonstrates how many of our social instifutions and psychological tendencies can be explained by the need to disbelieve in mortality.3 As I studied the ancestry of these evasions in Jacobean culture for my book The Rest is Silence: Death as Annihilation in the English Renaissance, I began noticing how ingeniously our own popular media abets our denials. The instances in novels and (especially) movies tend to be quite ffansparent: a thousand machine-gun bullets barely miss our beloved super-spy, a mourned side- kick tums up alive after all, and love stories extend into the happily ever after. -

February the Nest

the thenestline.comest February 2021 • Vol. 8 Issue 4 Boys Soccer Shoot For the Win Junior Bryce Shockley takes control of the ball and keeps it from the opponent. INSIDE TOMPKINS HIGH SCHOOL News ......................... 3 Features ................... 4 Cultural Sports ...................... 11 Identities Entertainment ........13 Gallery .................... 16 The Importance of Learning and Exploring Cultures Pages 8-9 4400 Falcon Landing Blvd. • Katy TX 77494 2 THE NEST CONTENTS Feburary 2021 Cover Photo By Caleigh Hommel Editor in Chief Sneha Raghavan Co-Managing Editors Everything About the Vaishnavi Bhat 3 Emma Vergara Covid-19 Vaccine Business and Social Manager Brianna Plake Layout Editor Ella Hummeldorf Staff Alkhatab Mizyed Ella Ray Madison Isom Mahee Bhatt Cowgirls in Cowtown Matias Simionato 7 Rachel Bregnard Raegan Ervin Tristan Beach Vanessa Caceres Vanessa Lingenfelter Head Photographers Caleigh Hommel Camvy Tu Asst. Head Photographers Taylor Hobson 10 Masked Falcon Morgan Cordle Photography Amber Gibson Angela Meza Arantza Dominguez Canela Babatise Awobokun Bridgette Foit Brinley Snyder Diego Cortez Ezri Terry Hadley Sanders Kalei Napolean Samantha Staff Appreciation Imouokhome 16 Tracy Thai Advisor Shetye Cypher @thenestline GENERAL INQUIRIES The Nest is an official publication of OTHS. Editorials represent the opinion of the writer, but not necessarily of KISD administration or faculty. The Nest is a member of the Inter- Tompkins High School scholastic League of Press Conference (ILPC), the Texas Association of Journalism Education (TAJE), the Journalism Education Association (JEA), the Columbia Scholastic Press 4400 Falcon Landing Blvd. Katy, Association (CSPA), the Texas High School Press Association (THSPA), and the National Scholastic Press Association (NSPA). It is the policy of KISD not to discriminate on the Tx 77494 basis of sex, disability, race, religion, color, age, or national origin and its educational programs, activites, and employment practices. -

Women in Prison: Mental Health and Well-Being

Women in prison: mental health and well-being A guide for prison staff Women in prison: mental health and well-being A guide for prison staff This guide has been prepared by Penal Reform International (PRI) and Prison Reform Trust UK (PRT) under the authorship of Sharon Critoph (consultant), Jenny Talbot (PRT), Vicki Prais and Olivia Rope (PRI). It has been produced with the financial assistance of the Better Community Business Network and the Eleanor Rathbone Charitable Trust. PRI and the PRT wish to acknowledge the contributions made by former women prisoners, women serving community sentences and people working with them. We also extend our gratitude to the international and national experts and practitioners from England and Wales, Canada, the World Health Organization, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the International Committee for the Red Cross for lending their expertise at a meeting held on 12 February 2019 in London, UK and subsequently. The guide was copy edited by Harriet Lowe. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of PRI and PRT and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of any of the donors. This publication may be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. Any changes to the text of this publication must be approved by PRI. Due credit must be given to PRI and PRT and to this publication. Enquiries should be addressed to [email protected]. Penal Reform International Headquarters 1 Ardleigh Road London N1 4HS Email: [email protected] Twitter: @PenalReformInt Facebook: @penalreforminternational www.penalreform.org Prison Reform Trust 15 Northburgh Street London EC1V 0JR Email: [email protected] Twitter: @PRTuk Facebook: @prisonreformtrust www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/women First published in February 2020 ISBN: 978-1-909521-66-7 © Penal Reform International / Prison Reform Trust 2020 IIlustrations by John Bishop. -

The Deaths of Socrates

Aleksander Kopka The Deaths of Socrates Key words: mourning, deconstruction, Plato, life, myth, auto-immunology, pharma- kon, writing The proper name would have sufficed, for it alone and by it- self says death, all deaths in one. It says death even while the bearer of it is still living. While so many codes and rites work to take away this privilege, because it is so terrifying, the proper name alone and by itself forcefully declares the unique disappearance of the unique — I mean the singulari- ty of an unqualifiable death [...] Death inscribes itself right in the name, but so as immediately to disperse itself there, so as to insinuate a strange syntax — in the name of only one to answer (as) many.1 and I imagine him unable to turn back on Plato. He is for- bidden to. He is in analysis and must sign, silently, since Plato will have kept the floor; signing what? well, a check, if you will, made out to the other, for he must have paid a lot, or his own death sentence. And first of all, by the same to- ken, the “mandate” to bring back that he himself dispatches to himself at the other’s command, his son or disciple, the one he has on his back and who will have played the devil’s advocate. For Plato finally says it himself, he sent it to him- 1 J. Derrida: The Deaths of Roland Barthes. Trans. P.-A. B r ault, M.Naas. In: Idem: The Work of Mourning. Chicago and London 2001, p. -

Lay Christian Views of Life After Death: a Qualitative Study and Theological Appraisal of the `Ordinary Eschatology' of Some Congregational Christians

Durham E-Theses Lay Christian Views of Life After Death: A Qualitative Study and Theological Appraisal of the `Ordinary Eschatology' of Some Congregational Christians ARMSTRONG, MICHAEL,ROBERT How to cite: ARMSTRONG, MICHAEL,ROBERT (2011) Lay Christian Views of Life After Death: A Qualitative Study and Theological Appraisal of the `Ordinary Eschatology' of Some Congregational Christians, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3274/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Michael Robert Armstrong Lay Christian Views of Life After Death: A Qualitative Study and Theological Appraisal of the ‘Ordinary Eschatology’ of Some Congregational Christians ABSTRACT The thesis investigates the life after death (hereafter LAD) beliefs of members of my Congregational church via in-depth semi-structured interviews. Complementary criteria of critical reflection and visible effect on behaviour are used to identify these views as „ordinary theology‟. -

The Study of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements Critical and Interdisciplinary Approaches

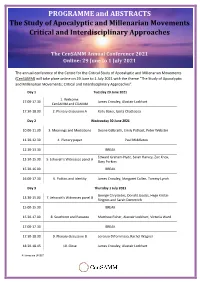

PROGRAMME and ABSTRACTS The Study of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements Critical and Interdisciplinary Approaches The CenSAMM Annual Conference 2021 Online: 29 June to 1 July 2021 The annual conference of the Centre for the Critical Study of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements (CenSAMM) will take place online on 29 June to 1 Ju ly 2021 with the theme “The Study of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements: Critical and Interdisciplinary Approaches”. Day 1 Tuesday 29 June 2021 1. Welcome: 17.00-17.30 James Crossley, Alastair Lockhart CenSAMM and CDAMM 17.30-18.30 2. Plenary discussion A Kelly Baker, Ipsita Chatterjea Day 2 Wednesday 30 June 2021 10.00-11.30 3. Meanings and Mediations Deane Galbraith, Emily Pothast, Peter Webster 11.30-12.30 4. Plenary paper Paul Middleton 12.30-13.30 BREAK Edward Graham-Hyde, Sarah Harvey, Zoe Knox, 13.30-15.30 5. Jehovah’s Witnesses panel A Gary Perkins 15.30-16.00 BREAK 16.00-17.30 6. Politics and Identity James Crossley, Margaret Cullen, Tommy Lynch Day 3 Thursday 1 July 2021 George Chryssides, Donald Jacobs, Hege Kristin 13.30-15.00 7. Jehovah’s Witnesses panel B Ringnes and Sarah Demmrich 15.00-15.30 BREAK 15.30-17.00 8. Southcott and Panacea Matthew Fisher, Alastair Lockhart, Victoria Ward 17.00-17.30 BREAK 17.30-18.30 9. Plenary discussion B Lorenzo DiTommaso, Rachel Wagner 18.30-18.45 10. Close James Crossley, Alastair Lockhart All times are UK/BST Registration and Participation There is no charge for attendance or participation. Attendance is by registration only; see the conference website for information: https://censamm.org/conferences/samm-2021 Joining instructions will be provided to participants shortly before the conference open. -

Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror Jenni A

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2011 Living in the Mystery: Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror Jenni A. Shearston Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Shearston, Jenni A., "Living in the Mystery: Myriad Approaches to Death in Edgar Allan Poe's Tales of Terror" (2011). All Regis University Theses. 550. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/550 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. -

Roll on 2021

Roll on 2021 Interview with homas Brodie-Sangster 14 Behind the lens No. 886 with White Lies Friday 29th January 2021 varsity.co.uk Music 20 Cambridge’s Independent Student Newspaper since 1947 Cambridge commemorates ifth anniversary of Giulio Regeni’s murder and independent trade unions in the Cameron White country. Senior News Editor he University’s commemorative Georgia Goble statement was released by Vice- News Correspondent Chancellor Professor Stephen Toope on Monday (25/01), describing Regeni’s Content note: his article contains a brief death as a “tragedy” and an “unbear- mention of torture able blow to his family and friends”. he Cambridge community has this “It horriied his university col- week commemorated Giulio Regeni leagues in Cambridge, Cairo, and following the ifth anniversary of his across the global academic com- murder in Egypt. munity. It was also an assault on the In a statement from the University, principle of academic freedom that Giulio is remembered as an “outward- underpins the work of all universities, looking scholar, brimming with intel- and which Giulio embodied”, the state- ligence, curiosity and compassion” ment continues. who showed “commitment to human he statement, which has so far rights, to his parents and wider fam- received over 700 signatures from ily.” students and staf alike (as of 26/01), A virtual vigil was held for Regeni emphasises the ongoing need to over Zoom on Sunday night (24/01), “defend the principle of academic organised by Amnesty International freedom”. It states that “the liberty Cambridge City Group (AICCG) and to pursue independent research is a Cambridge UCU, and featuring state- cornerstone of global scholarship” and ments from Vicky Blake, National that academics “should never be at President of the University and College risk of harm for following their intel- Union (UCU), Daniel Zeichner, Labour lectual curiosity, for collecting original MP for Cambridge, and Debora Singer, data, or for seeking evidence to verify Amnesty International’s Country Coor- or challenge ideas.” dinator for Egypt. -

2 September 2016

SEPTEMBER 2 - SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 VOL. 33 - ISSUE 18 ORANGE BLOSSOM FESTIVAL 17 - 18 SEPTEMBER CASTLE HILL SHOWGROUND Orange Blossom Festival is back with rides, kids zone, markets, foods, live entertainment, community stalls, fireworks, parade and so much more. For more details visit www. orangeblossomfestival.com.au BOUTIQUE FURNITURE Sandstone AND GIFTS Sales MARK VINT Buy Direct From the Quarry 9651 2182 Mention code QCHS0616 for 270 New Line Road 10% off the online rate 9652 1783 Dural NSW 2158 Specialising in corporate and [email protected] leisure accommodation. Handsplit ABN: 84 451 806 754 Group bookings available including sports groups, wedding guest groups, etc Random Flagging $55m2 Shop 1, 940 Old Northern Road, Glenorie, NSW 2157 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie WWW.DURALAUTO.COM (02) 9652 2552 Ph 02 88481500 ELECTRICIAN Domestic & Commercial Lighting, Powerpoints, Sensor Lights, Ceiling Fans, Smoke Detectors, Hot Water. No job too big or small 9680 2400 Timely, Tidy & Trusted™ 1300 045 103 Lic. No. 180022C An eclectic oasis in the heart of Glenorie FUSION ART • PHOTOGRAPHY • VINTAGE COLLECTIBLES An eclectic oasis in the heart of Glenorie Run and operated by the artists Ulla and Bjorn The UB Art Shack 2 Cairnes Road, Glenorie NSW 2157 Thur & Fri 12pm - 5pm, Sat & Sun 10am - 5pm 唀䈀 䄀爀琀 匀栀愀挀欀 Ph: Ulla - 0414 180 971 or Bjorn - 0419 242 844 E: [email protected] W: www.ubartshack.com.au FB: Ulla and Bjorn’s Art Shack MENTIONBUY A THIS DOZEN, AD QUALITY WINES, & RECEIVE 2 FREE CRAFT BEERS & SPIRITS BOTTLES FAMILY OWNED AND OPERATED 1669 Old Northern Road Glenorie | Ph 1300 76 78 73 IN THIS ISSUE CONTENTS In This Issue 3 Memories 5 Living Legends 7 History 12 Health & Wellbeing 13 Your Garden 15 As We Were 17 Local Politicians Say 23 The Hills & Beyond 25 The Greying Nomad 27 Hill’s Sustainable Communities Conference with Robyn Moore LETTER FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK Community Groups 28 Congratulations to Laura Rittenhouse who is our first winner of the My Garden competition.