Copyright by Tyson Sheldon Echelle 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Actor En El Star System Argentino ¿Trabajador Privilegiado O Mero Producto?

ISSN 1669-6301 245 DOSSIER [245-254] telóndefondo /27 (enero-junio, 2018) El actor en el star system argentino ¿Trabajador privilegiado o mero producto? Marta Casale " Instituto de Historia del Arte Argentino y Latinoamericano “Luis Ordaz”, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 30/03/2018. Fecha de aceptación: 23/04/2018. Resumen A pesar de que las investigaciones sobre el cine clásico-industrial argentino han Palabras clave aumentado considerablemente el último tiempo, aún son relativamente pocas las Star-system; que abordan el tema, muchos menos las que hacen foco en el sistema de estrellas estrella; actor/trabajador; en particular. Los escasos trabajos que lo hacen, por otro lado, suelen centrarse en cine industrial; determinadas figuras o en los films que éstas protagonizan, sin dar mayor relevancia sistema de estudios a las condiciones que lo posibilitan o al contexto económico del cual es fruto. En casi todos ellos, se resalta la condición de “producto a consumir” de la estrella, dejando de lado su calidad de trabajador, en parte, porque para algunos esa categorización parece oponerse a su condición de artista, en parte, porque para otros el desempeño interpretativo de la star es casi nulo, siendo ésta un producto basado solo en su físico y su personalidad, ambos especialmente pulidos para su “venta”. El siguiente artículo se propone analizar el sistema de estrellas en Argentina, prestando especial atención a los actores y actrices que lo conformaron, como así también a las razones de su aparición y formas particulares que adoptó en nuestro país. Ambiciona, además, plantear algunas preguntas sobre la específica condición de trabajador de la estrella, dentro de un sistema indudablemente capitalista. -

A Paula Ortiz Film Based on “Blood Wedding”

A Paula Ortiz Film A PAULA ORTIZ FILM INMA ÁLEX ASIER CUESTA GARCÍA ETXEANDÍA Based on “Blood Wedding” from Federico García Lorca. A film produced by GET IN THE PICTURE PRODUCTIONS and co-produced by MANTAR FILM - CINE CHROMATIX - REC FILMS BASED ON BLOOD WEDDING THE BRIDE FROM FEDERICO GARCÍA LORCA and I follow you through the air, like a straw lost in the wind. SYNOPSIS THE BRIDE - Based on “Blood Wedding” from F. García Lorca - Dirty hands tear the earth. A woman’s mouth shivers out of control. She breathes heavily, as if she were about to choke... We hear her cry, swallow, groan... Her eyes are flooded with tears. Her hands full with dry soil. There’s barely nothing left of her white dress made out of organza and tulle. It’s full of black mud and blood. Staring into the dis- tance, it’s dicult for her to breathe. Her lifeless face, dirtied with mud, soil, blood... she can’t stop crying. Although she tries to calm herself the crying is stronger, deeper. THE BRIDE, alone underneath a dried tree in the middle of a swamp, screams out loud, torn, endless... comfortless. LEONARDO, THE GROOM and THE BRIDE, play together. Three kids in a forest at the banks of a river. The three form an inseparable triangle. However LEONARDO and THE BRIDE share an invisible string, ferocious, unbreakable... THE GROOM looks at them... Years have gone by, and THE BRIDE is getting ready for her wedding. She’s unhappy. Doubt and anxiety consume her. She lives in the middle of white dessert lands, barren, in her father’s house with a glass forge. -

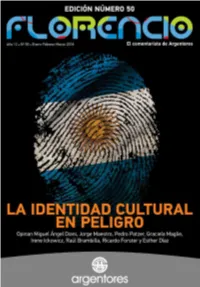

Florencio 1 Editorial

FLORENCIO 1 EDITORIAL EDICIÓN 50 ciden en aceptar los invitados a opinar en la nota principal de ese número, que se relaciona con los A TODO COLOR peligros que asedia a la identidad cultural de los argentinos en la actualidad. Y, por hablar de una herencia muy precisa, este número 50 de Florencio no puede dejar de evocar la entrañable figura de Carlos Pais, drama- on este número, Florencio llega a su turgo y dirigente de Argentores e impulsor de la quincuagésima edición, una nueva esca- iniciativa que llevó hace 14 años a la Junta Direc- Cla en un camino que ya lleva 14 años de tiva a decidir que esta revista comenzara a publi- marcha y que nos llena de satisfacción a quienes carse. A nueve años del fallecimiento de Pais, que le damos forma cada trimestre. A lo largo de todos se cumplirá en julio próximo, ninguno de los que estos años, esta publicación trató, dentro de los trabajamos a su lado o tuvimos la dicha de dis- márgenes en que se movía, de evolucionar, de me- frutar su amistad, puede olvidar la nobleza de sus jorar la calidad de sus entregas. No somos, desde convicciones solidarias, su ejemplar transparencia luego, los más indicados para evaluar si esa meta como persona y ese humor imbatible que, sin per- se logró, aunque sea en parte, pero quedan como der nunca el sentido de la responsabilidad, que en evidencia de ese deseo permanente de cambio los su caso era intenso, acompañaban y guiaban los distintos formatos que ella fue adquiriendo a tra- actos de su vida y que, por efecto reflejo, acariciaba vés del tiempo, el aumento constante de la canti- también las nuestras. -

Dayhá. PROYECTO DE RESOLUCION LA HONORABLE

2 3 1 EXPTE. D- /13-14 th: MU09204 QÇÇges Q.7420/2eaéle COSIca dayhá. PROYECTO DE RESOLUCION LA HONORABLE CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS DE LA PROVINCIA DE BUENOS AIRES RESUELVE De recordatorio por el "25 Aniversario del fallecimiento de Alberto Orlando OLMEDO", actor y humorista argentino. JORGE DO GO SCIPIONI 'o Bloque F ra la Victoria -PJ H. C. Dipu de la Prov. Da. As. b Tumn64 2c12),e4 COalea thqffrld;7"06 FUNDAMENTOS Alberto Orlando Olmedo, conocido también como El negro Olmedo, fue un actor y humorista argentino, considerado popularmente como uno de los "capocómicos" más importantes en la historia del espectáculo de la Argentina, por su destacada labor en televisión, cine y teatro. Alberto Orlando Olmedo nació el 24 de agosto de 1933 en la ciudad de Rosario y vivió durante toda su infancia y adolescencia junto a su madre, Matilde Olmedo, en la calle Tucumán 2765 del humilde barrio Pichincha. A los seis años, además de concurrir a la Escuela n.o 78 Juan F. Seguí, trabajó en la verdulería y carnicería de José Becaccece, en la calle Salta 3111. En 1947, por intermedio de Salvador Chita Naón, se integra a la claque del teatro La Comedia. Al año siguiente, con su amigo Osvaldo Martínez se incorpora al Primer Conjunto de Gimnasia Plástica en el Club Atlético Newell's Old Boys de Rosario. Por esa época también participa en una agrupación artística vocacional que funciona en el Centro Asturiano: La Troupe Juvenil Asturiana. En 1951, como parte de los números de La Troupe, forma junto a Antonio Ruiz Viñas, el dúo Toño-Olmedo. -

La Codicia Y Los Derechos

EDITORIAL La codicia y los derechos os autores celebraron en setiempre pasado un nuevo aniversario de su día. Lo hi- cieron en el legendario teatro Maipo en una ceremonia tan agradable y cálida como ajustada. La crónica de las páginas siguientes a este editorial da cuenta de cómo se desarrolló el acto, de sus discursos, de los premios y de sus felices ganadores. El de setiembre es una fecha en la que Argentores evoca su creación como entidad nacida para defender los derechos de los autores, esos derechos que, aunque consagrados por una ley, siguen siendo acosados por los intereses de grupos y corporaciones más inclinadas a incrementar sus ganancias que a respetar las prescripciones del ámbito legal, más acostum- braas a usufructuar lo ajeno que a cultivar la equidad. Los turbulentos vientos desatados en octubre sobre el escenario financiero de los Estados Unidos -a raíz de la quiebra de varios grandes bancos, auxiliados ahora por el Estado- han demostrado hasta que punto son capaces de llegar esas corporaciones cuando el Estado, la ley, no regula su apetito desmedido. Digamos, de paso, que también fue en el poderoso país del norte donde los autores y guionistas pro- fesionales impulsaron una de las huelgas más importantes de las últimas décadas en defensa de sus dere- chos, violados por el uso permanente de sus trabajos en Internet y otros medios sin el pago correspondien- te de una contraprestación. Esa lucha logró que muchas de las demandas fueran finalmente reconocidas. Se podría alegar que el caso de los bancos es mucho más grave que cualquiera de las expresiones de codicia que habitualmente contemplamos o vivimos en estas latitudes. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Memòria D'activitats 2018

MEMÒRIA D’ACTIVITATS 2018 GENER Divendres 12 de gener LATcinema: ‘Una noche sin luna’ (Uruguai) Projecció de la pel·lícula Una noche sin luna (Uruguai, 2014, 78'), una comèdia dirigida per Germán Tejeira. Durant la nit de Cap d'Any, tres personatges solitaris arriben a un petit poble perdut del camp uruguaià, on tindran una oportunitat per canviar el seu destí en l'any que comença. 2014: Festival de Sant Sebastià: Secció oficial (Nous Realitzadors) "Tejeira evita caure en el miserabilisme, no jutja ni tortura les seves criatures esmarrides, i domina el mitjà amb un to amable i eficaç. Una pel·lícula petita, entranyable i atractiva." Diego Batlle: Diari La Nación “Una noche sin luna retrata amb delicadesa i tendre enginy una nit en la vida de tres ànimes solitàries i desarrelades". Jonathan Holland. The Hollywood Reporter "El director esquiva tant el desdeny i la crueltat cap als seus personatges com la gratuïtat del cop d'efecte dramàtic: així aconsegueix una amable entramat coral, amb línies millor resoltes que altres, però amb un pols ferm per al costumisme." Diego Brodersen: Diari Página 12 Projecció amb el suport del Consolat General de l’Uruguai a Barcelona. Dijous 18 de gener Presentació de la Bolivianita, Gemma Emblemàtica de l’Estat Plurinacional de Bolívia La bolivianita és una gemma de Bolívia única en el món. Per iniciativa del consolat general de Bolívia a Barcelona, l’activitat de presentació inclou l’exposició de diversos exemplars d’aquesta pedra preciosa. La bolivianita –un tipus peculiar de quars bicolor (violeta i groc) de contractura d’ametista i citrina fusionats de manera natural– prové d’una regió selvàtica propera amb la frontera amb el Brasil i va ser descoberta l’any 1983 per Rodolfo Meyer: després de quasi tres mesos d’exploració per l’amazonia cruceña va coincidir amb un indígena que duia la gemma esmentada, desconeguda aleshores. -

Le Folk (12/04/2013)

Dossier d’accompagnement de la conférence / concert du vendredi 12 avril 2013 programmée en partenariat avec le Centre Culturel de Cesson-Sévigné dans le cadre du Programme d’éducation artistique et culturelle de l’ATM. Conférence-concert “LE FOLK” Conférence de Jérôme Rousseaux Concert de Haight-Ashbury Dans son sens le plus large, la musique folk désigne l’ensemble des musiques d’un pays ou d’une région du monde en particulier, souvent de tradition orale (on parle alors de musiques "folkloriques"). S’il est lui aussi rattaché à cette dimension “traditionnelle” à travers ses pionniers, le folk auquel nous nous intéresserons lors de cette conférence qualifie plus précisément une famille musicale d’origine anglo-saxonne (la "folk music") qui a bouleversé l’échiquier des musiques actuelles à partir des années soixante, notamment à travers la personnalité charismatique de Bob Dylan. Nous parlerons ici de la parenté que la musique folk entretient avec le blues, la Afin de compléter la lecture de ce musique country, les musiques traditionnelles et les musiques populaires en dossier, n'hésitez pas à consulter général. les dossiers d’accompagnement Puis, après avoir montré qu’il s’agit d’une esthétique qui passe sans doute plus des précédentes conférences- que les autres par une suite de mouvements revivalistes, et qui porte souvent concerts ainsi que les “Bases de en elle une certaine forme de sincérité et une notion d’engagement, nous données” consacrées aux éditions constaterons que le folk, récemment associé à des approches comme le lo-fi ou 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, en tant que composante de l’"americana", est aujourd’hui une musique à la fois 2010, 2011 et 2012 des Trans, multiforme et universelle. -

Shima-Uta:” of Windows, Mirrors, and the Adventures of a Traveling Song

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “SHIMA-UTA:” OF WINDOWS, MIRRORS, AND THE ADVENTURES OF A TRAVELING SONG A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Music by Ana-Mar´ıa Alarcon-Jim´ enez´ Committee in charge: Nancy Guy, Chair Anthony Burr Anthony Davis 2009 Copyright Ana-Mar´ıa Alarcon-Jim´ enez,´ 2009 All rights reserved. The thesis of Ana-Mar´ıa Alarcon-Jim´ enez´ is ap- proved, and it is accepted in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically : Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii DEDICATION To my family and my extended family (my friends from everywhere). iv EPIGRAPH Collective identity is an ineluctable component of individual identity. However, collec- tive identity is also a need that is felt in the present, and that stems from the more funda- mental need to have a sense of one’s own existence. We are given this sense of existence through the eyes of others, and our collective belonging is derived from their gaze. I am not nothing nor nobody: I am French, a youth, a Christian, a farmer... (Todorov 2003, 150) v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page............................................ iii Dedication.............................................. iv Epigraph...............................................v Table of Contents.......................................... vi List of Figures............................................ vii Acknowledgements........................................ viii Abstract of the Thesis....................................... ix Chapter 1. Introduction......................................1 1.1. Itinerary of a Traveling Song............................1 1.2. Background and Questions Addressed......................4 Chapter 2. Before Departure: Shimauta...........................6 2.1. Okinawa: A Brief Overview............................6 2.2. About Shimauta....................................8 2.3. Amami Shimauta...................................8 2.4. -

Polaroid De Locura Ordinaria. Cine Y Sociedad En Los Años Setenta

XI Jornadas de Sociología. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, 2015. Polaroid de locura ordinaria. Cine y sociedad en los años setenta. Melisa Redondo. Cita: Melisa Redondo (2015). Polaroid de locura ordinaria. Cine y sociedad en los años setenta. XI Jornadas de Sociología. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-061/343 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Polaroid de locura ordinaria. Cine y sociedad en los años setenta Melisa Redondo ([email protected]) Sociología UBA Resumen Este trabajo se propone indagar acerca de la relación entre cine y sociedad durante los años setenta. A partir del análisis de un conjunto de películas producidas por la empresa Aries Cinematográfica Argentina y protagonizadas por Alberto Olmedo y Jorge Porcel entre 1973 y 1982, se busca, en primer lugar, identificar los géneros y temáticas recurrentes en estas producciones, en segundo lugar, estudiar el modo en que interactuaban con representaciones sociales, y por último, establecer los cambios y las continuidades entre los períodos previo y posterior al golpe militar de 1976. Al mismo tiempo, la investigación tiene como objetivo secundario estudiar en un tiempo histórico concreto el grado de autonomía y dependencia de la industria cinematográfica respecto del poder político. Palabras clave Dictadura, clases medias, cine argentino Introducción La larga década del setenta estuvo marcada por tres hitos que permiten caracterizarla nítidamente. -

Universidad De San Andrés Departamento De Ciencias Sociales Licenciatura En Comunicación

Universidad de San Andrés Departamento de Ciencias Sociales Licenciatura en Comunicación “Por nosotras” Análisis de los personajes femeninos en las películas nacionales más vistas de los últimos 50 años Autora: Camila López Legajo: 27263 Mentora de Tesis: Belén Igarzábal Buenos Aires, Argentina 9/12/2020 Abstract El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar cómo se construyen los personajes principales femeninos en las películas más vistas de Argentina de los últimos 50 años. En un contexto de cambios, de mayor visibilización y ampliación de las luchas feministas, analizaremos 25 películas argentinas con el objetivo de responder dos preguntas: 1. A lo largo de los años, ¿Hubo en el cine nacional modelos convencionales y estereotipados de representar a la mujer como un objeto o con un rol doméstico? De ser positiva la respuesta ¿Hasta qué punto la mujer logra independizarse por completo de ese estereotipo? 2. ¿De qué manera la relación público-privada se pone en evidencia en los roles femeninos de las películas nacionales de los últimos 50 años? Para ello, en la primera pregunta de investigación se realizará un análisis cualitativo de casos. Mientras que para la segunda, un análisis de contenido cuantitativo. De modo que al unir ambos resultados nos permiten observar si hubo una evolución o cambio en la construcción de los personajes analizados. 1 Índice 1. Introducción 3 2. Marco teórico 4 2.1 Género 4 2.2 Espacio privado y espacio público 7 2.3 Mirada de género en el cine 8 3. Antecedentes 10 4. Pregunta de investigación 14 5. Metodología de la investigación 15 5.1 Justificativos 15 5.2 Muestra y universo 16 5.3 Análisis de caso 18 5.4 Análisis de contenido 20 6. -

Espectaculos Cine

CINE JAZZ TEATRO VARIEDADES ESPECTACULOS MUSICA BALLET Una denuncia y una elegía PAULA CAUTIVA. Argentina. 1963. Producción, Arles Cinematográfica. Productores, Fernando Ayala y Héc tor Olivera. Dirección, Fernando Aya- la. LtBreto cinematográfico del mis mo y Beatriz Guido sobre un cuento de la ultima (“La representación”). Fotografía, Alberto Etchebehere. Es cenografía. Mario Vanarell!. Música, Astor Piazzolla. Con Susana Freyre, Duilio Marzio, Lautaro Murúa, Leo nardo Favio, Fernando Mistral, Ores tes Caviglia, Crandall Dlehl, Merce des Sombra. Lola Palombo, Claudia Fontán, Oscar Caballero, Marta Mu- rat, Ricardo Florembaum. Estrenada en el Ambassador, lunes 11. Hay aquí uno de los grandes temas del cine argentino: el contraste entre la Ar gentina que enseñan los textos de His toria Patria, la Argentina de la Tradi ción Estanciera, la Argentina que Eduar do Mallea calificó de “visible”, y esa otra Argentina que desde Perón ha empezado a borrar y esconder a la otra, la Argen tina real. El punto de partida es una anécdota trivial, casi periodística. La des- I cendiente de una de las familias estan- j cieras del pasado (Susana Freyre) es aho ra una call-girl de lujo, para uso exclu sivo de los norteamericanos que vienen a cerrar Jugosos contratos en dólares en la vecina orilla. Su abuelo, que ella llama Grandpapa en el mejor estilo francés de la vieja oligarquía (Orestes Caviglia), uti liza lo que queda de su estancia, “La Cautiva”, para entretener a los turistas norteamericanos, ofreciéndoles espectácu los “típicos”. Ambos están vendidos al dólar, aunque la manera del anciano tie Lautaro Murúa con la Casa Rosada al fondo.