A Brave New Step: Why the Music Industry Should Follow the Hulu Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Free C Ulture Forum

Free C ulture Free C ulture Forum March 23, 2006 11:30 am - 2:30 pm 450 Dodge Hall, Northeastern University PROGRAM Welcome Dani Capalbo NU Student, Class of 2010 Edward A. Warro Dean of Libraries Introduction of Panelists Marcus Breen Communication Studies Panelists Lawrence Lessig Derek Slater Nelson Pavlosky Will Wakeling Bios Additional Resources Lawrence Lawrence Lessig is a Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and founder of the school's The World Wide Web holds many examples of projects whose intent is to facilitate Center for Internet and Society. Prior to joining the Stanford faculty, he was the Berkman the sharing of ideas, scholarly research and creative works. Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and a Professor at the University of Chicago. He clerked for Judge Richard Posner on the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals and Justice Antonin Scalia on the United States Supreme Court. Professor Lessig represented web site operator Creative Commons (http://creativecommons.org/) is a nonprofit organization that Eric Eldred in the ground-breaking case Eldred v. Ashcroft, a challenge to the 1998 Sonny offers flexible copyright licenses for original works; creators may choose from a range Bono Copyright Term Extension Act. He has won numerous awards, including the Free of protections and freedoms. Software Foundation's Freedom Award, and was named one of Scientific American's Top 50 Visionaries, for arguing "against interpretations of copyright that could stifle innovation and Creative Commons Education (http://creativecommons.org/education/) helps with online discourse online." Professor Lessig is the author of Free Culture (2004), The Future of Ideas publishing of educational materials. -

Open but Not Free — Publishing in the 21St Century Martin Frank, Ph.D

PERSPECTIVE For the Sake of Inquiry and Knowledge Research culture is far from knowledge. The new technology Disclosure forms provided by the author are available with the full text of this arti- monolithic. Systems that underpin is the internet. The public good cle at NEJM.org. scholarly communication will mi- they make possible is the world- grate to open access by fits and wide electronic distribution of From MIT Libraries, Massachusetts Insti- starts as discipline-appropriate op- the peer-reviewed journal litera- tute of Technology, Cambridge. tions emerge. Meanwhile, experi- ture and completely free and un- 1. Budapest Open Access Initiative (http:// ments will be run, start-ups will restricted access to it by all scien- www.opensocietyfoundations.org/ flourish or perish, and new com- tists, scholars, teachers, students, openaccess/read). munication tools will emerge, and other curious minds.” 2. Bethesda Statement on Open Access Pub- lishing (http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/ because, as the Bethesda Open There is no doubt that the pub- handle/1/4725199/suber_bethesda Access Statement puts it, “an old lic interests vested in funding .htm?sequence=1). tradition and a new technology agencies, universities, libraries, 3. Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities have converged to make possible and authors, together with the (http://www.zim.mpg.de/openaccess-berlin/ an unprecedented public good. power and reach of the Internet, berlin_declaration.pdf). The old tradition is the willingness have created a compelling and nec- 4. Suber P. Open access. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. of scientists and scholars to pub- essary momentum for open ac- 5. -

Digital Distribution

HOW DIGITAL DISTRIBUTION AND EVALUATION IS IMPACTING PUBLIC SERVICE ADVERTISING Aggressive Promotion Yields Significant Results By Bill Goodwill & James Baumann It is no surprise to see that digital distribution of all media products is fast becoming the de facto standard for distribution of media content, particularly for shorter videos such as PSA messages. First let’s define the terms. Digital distribution (also called digital content delivery, online distribution, or electronic distribution), is the delivery of media content online, thus bypassing physical distribution methods, such as video tapes, CDs and DVDs. In additional to saving money on tapes and disks, digital distribution eliminates the need to print collateral materials such as storyboards, newsletters, bounce-back cards, etc. Finally, it provides the opportunity to preview messages online, and offers media high- quality files for download. The “Pull” Distribution Model In the pre-digital world, the media was spoiled because they had all the PSA messages they could ever use delivered right to their desktop, along with promotional materials explaining the importance of the campaigns. Today, the standard way for stations to get PSAs in the digital world is to go to a site created by the digital distribution company and download them from the “cloud.” Using a dashboard that has been created for PSAs, the media can preview the spots and download both the PSAs, as well as digital collateral materials such as storyboards, a newsletter and traffic instructions. This schematic shows the overall process flow for digital distribution. To provide more control over digital distribution, Goodwill Communications has its own digital distribution download site called PSA Digital™, and to see how we handle both TV and radio digital files, go to: http://www.goodwillcommunications.com/PSADigital.aspx. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

Joy Harjo Reads from 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library

Joy Harjo Reads From 'Crazy Brave' at the Central Library [0:00:05] Podcast Announcer: Welcome to the Seattle Public Library's podcasts of author readings and Library events; a series of readings, performances, lectures and discussions. Library podcasts are brought to you by the Seattle Public Library and Foundation. To learn more about our programs and podcasts visit our website at www.spl.org. To learn how you can help the Library Foundation support the Seattle Public Library go to foundation.spl.org. [0:00:40] Marion Scichilone: Thank you for joining us for an evening with Joy Harjo who is here with her new book Crazy Brave. Thank you to Elliot Bay Book Company for inviting us to co-present this event, to the Seattle Times for generous promotional support for library programs. We thank our authors series sponsor Gary Kunis. Now, I'm going to turn the podium over to Karen Maeda Allman from Elliott Bay Book Company to introduce our special guest. Thank you. [0:01:22] Karen Maeda Allman: Thanks Marion. And thank you all for coming this evening. I know this is one of the readings I've most look forward to this summer. And as I know many of you and I know that many of you have been reading Joy Harjo's poetry for many many years. And, so is exciting to finally, not only get to hear her read, but also to hear her play her music. Joy Harjo is of Muscogee Creek and also a Cherokee descent. And she is a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa. -

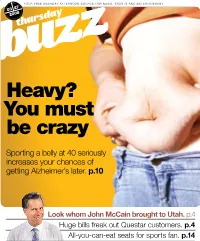

Heavy? You Must Be Crazy

YOUR FREE WEEKDAY AFTERNOON SOURCE FOR NEWS, SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 03 27 2008 Heavy? You must be crazy Sporting a belly at 40 seriously increases your chances of getting Alzheimer’s later. p.10 Look whom John McCain brought to Utah. p.4 Huge bills freak out Questar customers. p.4 All-you-can-eat seats for sports fan. p.14 SOMETHING TO BUZZ ABOUT Bartender, Another Hemotoxin Please Murder Suspect Not a Flight Risk A Texas rattlesnake rancher found Popplewell said his intent is not A morbidly obese Texas woman Mayra Lizbeth Rosales, who a new way to make money: Stick a to sell an alcoholic beverage but a who authorities originally thought weighs at least 800 pounds and is rattler inside a bottle of vodka and healing tonic. He said he uses the might have crushed her 2-year-old bedridden, was photographed and market the concoction as an “an- cheapest vodka he can find as a nephew to death was arraigned in fingerprinted at her La Joya home cient Asian elixir.” But Bayou Bob preservative for the snakes. The her bedroom Wednesday on a cap- before being released on a per- Popplewell has no liquor license and end result is a super sweet mixed ital murder charge, accused of strik- sonal recognizance bond, Hidalgo faces charges. drink he compared to cough syrup. ing him in the head. County Sheriff Lupe Trevino said. 27mar08 TheWeather Tonight Partly cloudy. 29° theprimer Sunset: 7:47 p.m. Friday 50° Mostly cloudy; 50 INTERNET percent chance of late rain and snow An Educational, Saturday and Fruitful, Site 45° Mostly cloudy; 40 A colorful, new interactive Web site, percent chance of rain designed to educate children ages 2 and snow. -

MUSIC and MOVEMENT in PIXAR: the TSU's AS an ANALYTICAL RESOURCE

Revis ta de Comunicación Vivat Academia ISSN: 1575-2844 Septiembre 2016 Año XIX Nº 136 pp 82-94 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2016.136.82-94 INVESTIGACIÓN/RESEARCH Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 MUSIC AND MOVEMENT IN PIXAR: THE TSU’s AS AN ANALYTICAL RESOURCE Diego Calderón Garrido1: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Josep Gustems Carncier: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Jaume Duran Castells: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] ABSTRACT The music for the animation cinema is closely linked with the characters’ movement and the narrative action. This paper presents the Temporary Semiotic Units (TSU’s) proposed by Delalande, as a multimodal tool for the music analysis of the actions in cartoons, following the tradition of the Mickey Mousing. For this, a profile with the applicability of the nineteen TSU’s was applied to the fourteen Pixar movies produced between 1995-2013. The results allow us to state the convenience of the use of the TSU’s for the music comprehension in these films, especially in regard to the subject matter and the characterization of the characters and as a support to the visual narrative of this genre. KEY WORDS Animation cinema, Music – Pixar - Temporary Semiotic Units - Mickey Mousing - Audiovisual Narrative – Multimodality 1 Diego Calderón Garrido: Doctor in History of Art, titled superior in Modern Music and Jazz music teacher and sound in the degree of Audiovisual Communication at the University of Barcelona. -

Who Pays for Music?

Who Pays For Music? The Honors Program Senior Capstone Project Meg Aman Professor Michael Roberto May 2015 Who Pays For Music Senior Capstone Project for Meg Aman TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... 3 LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 4 MUSIC INDUSTRY BACKGROUND ...................................................................................... 6 THE PROBLEM .................................................................................................................. 8 THE MUSIC INDUSTRY ..................................................................................................... 9 THE CHANGING MUSIC MARKET .................................................................................... 10 HOW CAN MUSIC BE FREE? ........................................................................................... 11 MORE OR LESS MUSIC? .................................................................................................. 12 THE IMPORTANCE OF SAMPLING ..................................................................................... 14 THE NETWORK EFFECTS ................................................................................................. 16 WHY STREAMING AND DIGITAL MUSIC STORES ............................................................ -

The Music Industry in the Social Networking Era

THE MUSIC INDUSTRY IN THE SOCIAL NETWORKING ERA By Xi Yue A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Telecommunication, Information Studies and Media 2011 Abstract THE MUSIC INDUSTRY IN THE SOCIAL NETWORKING ERA By Xi Yue Music has long been a pillar of profit in the entertainment industry, and an indispensable part in many people’s daily lives around the world. The emergence of digital music and Internet file sharing, spawned by rapid advancement in information and communication technologies (ICT), has had a huge impact on the industry. Music sales in the U.S., the largest national market in the world, were cut in half over the past decade. After a quick look back at the pre-digital music market, this thesis provides an overview of the music industry in the digital era. The thesis continues with an exploration of three motivating questions that look at social networking sites as a possible major outlet and platform for musical artists and labels. A case study of a new social networking music service is presented and, in conclusion, thoughts on a general strategy for the digital music industry are presented. Table of Contents List of Figures................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables................................................................................................................................... v Introduction.................................................................................................................................... -

Brave Waiting No

Sermon #1371 Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit 1 BRAVE WAITING NO. 1371 A SERMON DELIVERED ON LORDS-DAY MORNING, AUGUST 26, 1877, BY C. H. SPURGEON, AT THE METROPOLITAN TABERNACLE, NEWINGTON. “Wait on the Lord: be of good courage and He shall strengthen your heart: wait, I say, on the Lord.” Psalm 27:14. THE Christian’s life is no child’s play. All who have gone on pilgrimage to the celestial city have found a rough road, sloughs of despond and hills of difficulty, giants to fight and tempters to shun. Hence there are two perils to which Christians are exposed—the one is that under heavy pressure they should start away from the path which they ought to pursue—the other is lest they should grow fearful of failure and so become faint-hearted in their holy course. Both these dangers had evidently occurred to David and in the text he is led by the Holy Spirit to speak about them. “Do not,” he seems to say, “do not think that you are mistaken in keeping to the way of faith. Do not turn aside to crooked policy. Do not begin to trust in an arm of flesh, but wait upon the Lord.” And, as if this were a duty in which we are doubly apt to fail, he repeats the exhortation and makes it more emphatic the second time, “Wait, I say, on the Lord.” Hold on with your faith in God. Persevere in walking according to His will. Let nothing seduce you from your integrity—let it never be said of you, “You ran well, what did hinder you that you did not obey the truth?” And lest we should be faint in our minds, which was the second danger, the psalmist says, “Be of good courage, and He shall strengthen your heart.” There is really nothing to be depressed about. -

Apple / Shazam Merger Procedure Regulation (Ec)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DG Competition CASE M.8788 – APPLE / SHAZAM (Only the English text is authentic) MERGER PROCEDURE REGULATION (EC) 139/2004 Article 8(1) Regulation (EC) 139/2004 Date: 06/09/2018 This text is made available for information purposes only. A summary of this decision is published in all EU languages in the Official Journal of the European Union. Parts of this text have been edited to ensure that confidential information is not disclosed; those parts are enclosed in square brackets. EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 6.9.2018 C(2018) 5748 final COMMISSION DECISION of 6.9.2018 declaring a concentration to be compatible with the internal market and the EEA Agreement (Case M.8788 – Apple/Shazam) (Only the English version is authentic) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 6 2. The Parties and the Transaction ................................................................................... 6 3. Jurisdiction of the Commission .................................................................................... 7 4. The procedure ............................................................................................................... 8 5. The investigation .......................................................................................................... 8 6. Overview of the digital music industry ........................................................................ 9 6.1. The digital music distribution value