Hong Kong: Other Histories, Other Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRIME MINISTER Lunch for Collea Ues You Were Concerned About The

PRIME MINISTER Lunch for Collea ues You were concerned about the list of colleagues which I put to you last night as possible guests for 18th April. 1 As you know, almost ail the Ministers of State and the Parliamentary Under Secretaries have now been included in a Monday lunch, and we are getting through the outstanding ones quite quickly. Three of the outstanding PUSSs are from the Scottish, Irish and Welsh Offices, and because they are not often in London on Mondays, I have liaised with their Private Offices for a suitable date_„ I know that James Douglas Hamilton and Peter Vidgers- are able to come on 18th April, and Ian Grist is available on 25th April. I know you are worried about the Senior/Junior mix. The last lunch was rather unbalanced because both John Wakeham and David Waddington were not present. This would not normally be the case, and I know that your invitations to senior backbenchers and to Parliamentary Private Secretaries have been very well received. However, you mav prefer to go through the list of Ministers of State again. Overleaf are two bossible lists for 18th April, and also two possible lists for 25th April (reserves in brackets). One set of lists includes senior backbenchers and PPSs, and one set reverts to Ministers of State. Please would you indicate which you prefer? • Page Two i8th APRIL John MacGregor (Lord Mackay) James Douglas-Hamilton Peter Viggers Mark Lennox-Boyd (Tristan Garel-Jones) Geoffrey Johnson-Smith (John Hannam or John MacGregor (Lord Mackay) David Mellor (Chris Patten) Tim Renton (John Patten) -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy

Loyola University Chicago International Law Review Volume 3 Article 5 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2006 2006 The aB sic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong Michael C. Davis Chinese University of Hong Kong Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Davis The Basic Law and Democratization in Hong Kong, 3 Loy. U. Chi. Int'l L. Rev. 165 (2006). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/lucilr/vol3/iss2/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago International Law Review by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BASIC LAW AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN HONG KONG Michael C. Davist I. Introduction Hong Kong's status as a Special Administrative Region of China has placed it on the foreign policy radar of most countries having relations with China and interests in Asia. This interest in Hong Kong has encouraged considerable inter- est in Hong Kong's founding documents and their interpretation. Hong Kong's constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law ("Basic Law"), has sparked a number of debates over democratization and its pace. It is generally understood that greater democratization will mean greater autonomy and vice versa, less democracy means more control by Beijing. For this reason there is considerable interest in the politics of interpreting Hong Kong's Basic Law across the political spectrum in Hong Kong, in Beijing and in many foreign capitals. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Britain and Europe

Britain and Europe ROBERT COOPER Forty years after Britain joined Europe both have changed, mostly for the better. This story does not, however, begin in 1972 when the negotiations finished and were ratified by parliament, nor in 1973 when the UK took its place at the Council table as a full member, but ten years before with the first British application and the veto by General de Gaulle. Sometimes, going further back still, it is suggested that if Ernest Bevin’s ideas for West European cooperation had been pursued,1 or if Britain had decided to join talks on the Schuman Plan,2 or to take the Spaak Committee seriously,3 things might have been different. But the truth is there was no Robert Schuman or Jean Monnet in Britain, and no readiness to think in radically new terms. Had the UK been present at the negotiations that led to the European Coal and Steel Community, the outcome for Britain would probably still have been the same, precisely because the vision was lacking. The decision on the Schuman Plan was a close-run thing—the idea of planning for heavy industry being in accordance with the ideas of the Labour government. But British ideas were very different from those of the French or the Americans, who were thinking in terms of supranational bodies—indeed, for Monnet this was a cardinal point. His approach was supported by the Benelux countries, which were already setting up their own customs union. Bevin had an ambition to lead Europe, but it is not clear where he wanted to take it. -

Conservative Party Leaders and Officials Since 1975

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07154, 6 February 2020 Conservative Party and Compiled by officials since 1975 Sarah Dobson This List notes Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975. Further reading Conservative Party website Conservative Party structure and organisation [pdf] Constitution of the Conservative Party: includes leadership election rules and procedures for selecting candidates. Oliver Letwin, Hearts and Minds: The Battle for the Conservative Party from Thatcher to the Present, Biteback, 2017 Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron, Polity Press, 2016 Robert Blake, The Conservative Party from Peel to Major, Faber & Faber, 2011 Leadership elections The Commons Library briefing Leadership Elections: Conservative Party, 11 July 2016, looks at the current and previous rules for the election of the leader of the Conservative Party. Current state of the parties The current composition of the House of Commons and links to the websites of all the parties represented in the Commons can be found on the Parliament website: current state of the parties. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Conservative Party leaders and officials since 1975 Leader start end Margaret Thatcher Feb 1975 Nov 1990 John Major Nov 1990 Jun 1997 William Hague Jun 1997 Sep 2001 Iain Duncan Smith Sep 2001 Nov 2003 Michael Howard Nov 2003 Dec 2005 David Cameron Dec 2005 Jul 2016 Theresa May Jul 2016 Jun 2019 Boris Johnson Jul 2019 present Deputy Leader # start end William Whitelaw Feb 1975 Aug 1991 Peter Lilley Jun 1998 Jun 1999 Michael Ancram Sep 2001 Dec 2005 George Osborne * Dec 2005 July 2016 William Hague * Dec 2009 May 2015 # There has not always been a deputy leader and it is often an official title of a senior Conservative politician. -

The Battle Over Democracy in Hong Kong, 19 N.C

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 19 | Number 1 Article 6 Fall 1993 Envisioning Futures: The aB ttle veo r Democracy in Hong Kong Bryan A. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Bryan A. Gregory, Envisioning Futures: The Battle over Democracy in Hong Kong, 19 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 175 (1993). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol19/iss1/6 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Envisioning Futures: The aB ttle veo r Democracy in Hong Kong Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol19/iss1/6 Envisioning Futures: The Battle Over Democracy in Hong Kong I. Introduction Hong Kong has entered its last years under British administration, and the dramatic final act is being played out.1 When Hong Kong reverts to Chinese rule, it will do so under the protection of the Basic Law,2 a mini-constitution created pursuant to a Joint Declaration 3 be- tween the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China (PRC) that delineates the principles under which Hong Kong will be gov- erned. The former and future rulers of the city diverge widely in their political, economic, and social systems, and despite the elaborate detail of the relevant treaties providing for the transfer,4 there have been disagreements during the period of transition. -

The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 the Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001

8 Philip Lynch The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 The Conservatives and Europe, 1997–2001 Philip Lynch As Conservatives reflected on the 1997 general election, they could agree that the issue of Britain’s relationship with the European Union (EU) was a significant factor in their defeat. But they disagreed over how and why ‘Europe’ had contributed to the party’s demise. Euro-sceptics blamed John Major’s European policy. For Euro-sceptics, Major had accepted develop- ments in the European Union that ran counter to the Thatcherite defence of the nation state and promotion of the free market by signing the Maastricht Treaty. This opened a schism in the Conservative Party that Major exacer- bated by paying insufficient attention to the growth of Euro-sceptic sentiment. Membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) prolonged recession and undermined the party’s reputation for economic competence. Finally, Euro-sceptics argued that Major’s unwillingness to rule out British entry into the single currency for at least the next Parliament left the party unable to capitalise on the Euro-scepticism that prevailed in the electorate. Pro-Europeans and Major loyalists saw things differently. They believed that Major had acted in the national interest at Maastricht by signing a Treaty that allowed Britain to influence the development of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) without being bound to join it. Pro-Europeans noted that Thatcher had agreed to an equivalent, if not greater, loss of sovereignty by signing the Single European Act. They believed that much of the party could and should have united around Major’s ‘wait and see’ policy on EMU entry. -

What Marxism Today Has Meant to Me

What Marxism Today Has Meant To Me Marxism Today anticipated the post- The end of Marxism Today is a moment socialist world and made a telling con- of sadness. Throughout the 80s its de- tribution to the debate about alterna- bates on politics and culture spoke di- tives to Thatcherism at a time when the rectly to me as a product of 60s liberta- Labour Party was intellectually mori- rianism and 70s leftism. Optimistically, bund. I'm sorry to see it go, but keenly I would hope that those debates are now anticipate the day when its successor part of the mainstream. Pessimistically, journal appears. I'm concerned that, as leninism is quite Hugo Young is a columnist on The Guar- rightly consigned to the ash-can of his- dian. tory, the project to link an understanding of economic activity to a politics of social transformation may be abandoned at It's always a matter of regret to see one the moment it is most urgently needed. expression of opinion shutting - it nar- Colin MacCabe is head of research at the rows the range of views available, and BFI. also the range of places I can send letters to - terrible! But I haven't agreed with much of what you've said in the 80s. From the beginning until the last Keith Flett is one of the most prolific number I was sometimes a contributor, letter-writers in Britain today. and all the time a very faithful reader. I don't think for a moment that the end of I shall miss Marxism Today more than the magazine somehow cancels its I'll miss the philosophy in whose name it Marxism Today has been open-minded achievement. -

What Happens to the United Kingdom Now? Project Syndicate - Oct 30, 2019 | CHRIS PATTEN

What happens to the United Kingdom now? Project Syndicate - Oct 30, 2019 | CHRIS PATTEN The United Kingdom’s Brexit psychodrama continues. Although the UK government and the European Union reached a revised withdrawal agreement in mid-October, Prime Minister Boris Johnson was unable to push the deal through Parliament so that the UK could leave the bloc by his hoped-for date of October 31. EU leaders have therefore granted a further three-month extension of the Brexit deadline until January 31, and the UK will now hold a parliamentary election on December 12. Johnson secured the withdrawal agreement partly by reversing his previous position and accepting a customs border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, and partly by settling for worse terms than his predecessor, Theresa May. What happens to the United Kingdom now? Project Syndicate - Oct 30, 2019 | CHRIS PATTEN It was Harold Macmillan, the UK’s prime minister in the early 1960s, who concluded that the country should join what was then the European Common Market to reverse systemic, long-term economic decline. 1) ________ 1951 and 1973, Britain ranked last 2) ________ OECD economies, with average growth of just 3) ________ per year. Japan grew the fastest, 4) ________ at an average annual pace of 9.5%, 5) ________ Germany, France, and Italy clocked in at 5% or above. Another Conservative prime 6) ________, Edward Heath, eventually got us through the 7) ________ door following the death of Charles de Gaulle, 8) ________ as France’s president had been 9) ________ inveterate opponent of UK membership. -

The Power to Change

to achieve even the most individualistic thing without having a broader social sense. You climb a mountain because The Power mountains are there, and if you climb a very high one you put a national flag on the top. I think it's a terribly inadequate way of looking at political philosophy to To Change assume such a split between the indi vidual and the collective or the com There has been a remarkable change in the munity, because people operate in both ways. I wrote in a widely-remaindered style and tone of government since John Major book a few years ago that people in a became prime minister. Are we witnessing the way express their individualism best in groups larger than themselves, in their birth of a new kind of Conservatism? family, in their church, their club and David Marquand interviews Chris Patten their school, and the collective, the social, is important to the working out of your individualism. So that is a fairly fundamental aspect of human behaviour patterns. It doesn't seem to me that it should be impossible for politicians to find a way of encapsulating it in terms of political argument. What may make it more difficult for us in this country is the extent to which political argument was polarised into absurdities and was very often institutionalised into absurdities as well, for example, the way such large sections of industry were nationalised. Chris Patten was appointed chairman of the Conservative Party last November. Do you think the social market concept that Previously he was secretary of state for the enivironment and minister for overseas you've just been talking about depends development. -

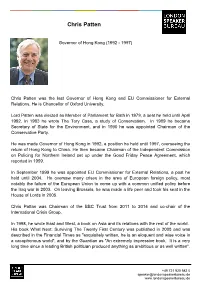

Chris Patten

Chris Patten Governor of Hong Kong (1992 - 1997) Chris Patten was the last Governor of Hong Kong and EU Commissioner for External Relations. He is Chancellor of Oxford University, Lord Patten was elected as Member of Parliament for Bath in 1979, a seat he held until April 1992. In 1983 he wrote The Tory Case, a study of Conservatism. In 1989 he became Secretary of State for the Environment, and in 1990 he was appointed Chairman of the Conservative Party. He was made Governor of Hong Kong in 1992, a position he held until 1997, overseeing the return of Hong Kong to China. He then became Chairman of the Independent Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland set up under the Good Friday Peace Agreement, which reported in 1999. In September 1999 he was appointed EU Commissioner for External Relations, a post he held until 2004. He oversaw many crises in the area of European foreign policy, most notably the failure of the European Union to come up with a common unified policy before the Iraq war in 2003. On leaving Brussels, he was made a life peer and took his seat in the House of Lords in 2005. Chris Pattan was Chairman of the BBC Trust from 2011 to 2014 and co-chair of the International Crisis Group. In 1998, he wrote East and West, a book on Asia and its relations with the rest of the world. His book What Next: Surviving The Twenty First Century was published in 2008 and was described in the Financial Times as "exquisitely written, he is an eloquent and wise voice in a cacophonous world", and by the Guardian as "An extremely impressive book.