The Five Main Themes of the Old Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Common Mistakes Courts Make When Police Lose Or Destroy Evidence with Apparent Exculpatory

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 48 Issue 2 Article 6 2000 Here Today, Gone Tomorrow - Three Common Mistakes Courts Make When Police Lose or Destroy Evidence with Apparent Exculpatory Elizabeth A. Bawden Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Evidence Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Elizabeth A. Bawden, Here Today, Gone Tomorrow - Three Common Mistakes Courts Make When Police Lose or Destroy Evidence with Apparent Exculpatory, 48 Clev. St. L. Rev. 335 (2000) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol48/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HERE TODAY, GONE TOMORROW - THREE COMMON MISTAKES COURTS MAKE WHEN POLICE LOSE OR DESTROY EVIDENCE WITH APPARENT EXCULPATORY VALUE ELIZABETH A. BAWDEN1 I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 336 II. CALIFORNIA V. TROMBETTA................................................... 338 III. ARIZONA V. YOUNGBLOOD..................................................... 339 IV. APPLICATION OF TROMBETTA ............................................... 341 V. APPLICATION OF YOUNGBLOOD............................................ 342 VI. WHAT CONSTITUTES APPARENT EXCULPATORY -

February 1992 1 William Hunt

February 1992 1 William Hunt................................................. Editor Ruth C. Butler ...............................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager ................................ Art Director Kim S. Nagorski............................ Assistant Editor Mary Rushley........................ Circulation Manager MaryE. Beaver.......................Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher ...................... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis ......................................Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc., 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, announcements and news releases about ceramics are welcome and will be consid ered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A booklet describing standards and proce dures for submitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Addition ally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) indexing is available through Wilsonline, 950 UniversityAve., Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Co., 362 Lakeside Dr., Forest City, Califor nia 94404. -

Proverbs Bibliography 2005

1 Proverbs: Rough and Working Bibliography Ted Hildebrandt Gordon College, 2005 ON Biblical Proverbs, Proverbial Folklore, and Psychology/Cognitive Literature 4 page Selected Bibliography + Full Bibliography Compiled by Ted Hildebrandt July 1, 2005 Gordon College, Wenham, MA 01984 [email protected] 2 Brief Selected Bibliography: Top Picks Alster, Bendt. The Instructions of Suruppak: A Sumerian Proverb Collection. Mesopotamia. Copenhagen Studies in Assyriology, vol. 2. Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, 1974. _______. Proverbs of Ancient Sumer: The World’s Earliest Proverb Collections. 2 vols. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 1997. Barley, Nigel. "A Structural Approach to the Proverb and the Maxim with Special Reference to the Anglo-Saxon Corpus." Proverbium 20 (1972): 737-50 Bostrom, Lennart. The God of the Sages: The Portrayal of God in the Book of Proverbs. (Stockholm: Coniectanea Biblica, OT Series 29, 1990). Bryce, Glendon E. A Legacy of Wisdom: The Egyptian Contribution to the Wisdom of Israel. London: Associated University Presses, 1979. Camp, Cladia V. Wisdom and the Feminine in the Book of Proverbs, (England: JSOT Press, 1985). Cook, Johann. The Septuagint of Proverbs: Jewish and/or Hellenistic Coloouring of the LXX Proverbs. VTSup 69. Leide, Brill, 1997. Crenshaw, James L., Old Testament Wisdom: An Introduction. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1981. ________, ed. Studies in Ancient Israelite Wisdom. New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1976. EXCELLENT! Dundes, Alan, "On the Structure of the Proverb." In Analytic Essays in Folklore. Edited by Alan Dundes. The Hague: Mouton and Company, 1975. Also in The Wisdom of Many. Essays on the Proverb. Ed by W. Mieder and Dundes 1981. Fontaine, Carol R. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Comic Book Collection

2008 preview: fre comic book day 1 3x3 Eyes:Curse of the Gesu 1 76 1 76 4 76 2 76 3 Action Comics 694/40 Action Comics 687 Action Comics 4 Action Comics 7 Advent Rising: Rock the Planet 1 Aftertime: Warrior Nun Dei 1 Agents of Atlas 3 All-New X-Men 2 All-Star Superman 1 amaze ink peepshow 1 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Ame-Comi Girls 2 Ame-Comi Girls 3 Ame-Comi Girls 6 Ame-Comi Girls 8 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld 9 Angel and the Ape 1 Angel and the Ape 2 Ant 9 Arak, Son of Thunder 27 Arak, Son of Thunder 33 Arak, Son of Thunder 26 Arana 4 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 1 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 5 Archer & Armstrong 20 Archer & Armstrong 15 Aria 1 Aria 3 Aria 2 Arrow Anthology 1 Arrowsmith 4 Arrowsmith 3 Ascension 11 Ashen Victor 3 Astonish Comics (FCBD) Asylum 6 Asylum 5 Asylum 3 Asylum 11 Asylum 1 Athena Inc. The Beginning 1 Atlas 1 Atomic Toybox 1 Atomika 1 Atomika 3 Atomika 4 Atomika 2 Avengers Academy: Fear Itself 18 Avengers: Unplugged 6 Avengers: Unplugged 4 Azrael 4 Azrael 2 Azrael 2 Badrock and Company 3 Badrock and Company 4 Badrock and Company 5 Bastard Samurai 1 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 27 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 28 Batman:Shadow of the Bat 30 Big Bruisers 1 Bionicle 22 Bionicle 20 Black Terror 2 Blade of the Immortal 3 Blade of the Immortal unknown Bleeding Cool (FCBD) Bloodfire 9 bloodfire 9 Bloodshot 2 Bloodshot 4 Bloodshot 31 bloodshot 9 bloodshot 4 bloodshot 6 bloodshot 15 Brath 13 Brath 12 Brath 14 Brigade 13 Captain Marvel: Time Flies 4 Caravan Kidd 2 Caravan Kidd 1 Cat Claw 1 catfight 1 Children of -

Federal Register Volume 32 • Number 89

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 32 • NUMBER 89 Tuesday, May 9,1967 • Washington, D.C. Pages 7007-7043 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Research Service Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Air Force Department Atomic Energy Commission Business and Defense Services Administration Civil Aeronautics Board Civil Service Commission Consumer and Marketing Service Defense Department Federal Aviation Administration Federal Communications Commission Federal Home Loan Bank Board Federal Power Commission Federal Trade Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Food and Drug Administration Housing and Urban Development Department Immigration and Naturalization Service Interstate Commerce Commission Labor Department Mines Bureau Panama Canal Public Contracts Division Reclamation Bureau Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration State Department Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Announcing First 10-Year Cumulation TABLES OF LAWS AFFECTED in Volumes 70-79 of the UNITED STATES STATUTES AT LARGE Lists all prior laws and other Federal in- public laws enacted during the years 1956- struments which were amended, repealed, 1965. Includes index of popular name or otherwise affected by the provisions of acts affected in Volumes 70-79. Price: $2.50 'Compiled by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 'i r m r n i i fir f'I C T m Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or r r l l r n / l l « n i i r | l | \ I r tl on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Register, National 1 a Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail address National Area Code 202 Phone 962-8626 Archives Building, Washington, D.C. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Hard Asphalt and Heavy Metals: Urban Environmentalism in Postwar America A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2008 By Robert R. Gioielli M.A., University of Cincinnati, 2004 B.A., University of South Carolina, 1999 Committee Chair: Professor David Stradling Abstract Hard Asphalt and Heavy Metals: Urban Environmentalism in Postwar America By Robert R. Gioielli After World War Two, American cities began to break down. Their housing and industrial infrastructure fell into disrepair, and efforts to improve cities, including urban renewal and highway construction projects, only exacerbated the existing problems, destroying neighborhoods and increasing pollution. All of these problems exposed city residents to a unique set of environmental problems. By the 1960s many of them responded to this environmental breakdown with a series of dynamic local social movements. For almost a decade, residents of scores of cities, especially in the East and Midwest, forced local leaders to ameliorate the impact of a variety of local environmental problems. This dissertation provides case studies of three of these local movements. In St. Louis, the rapid decline of the city’s housing stock exposed poor, predominantly African American city children to toxic levels of lead paint. -

Savage Dragon Archives: V. 1 PDF Book

SAVAGE DRAGON ARCHIVES: V. 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erik Larsen | 616 pages | 22 Jan 2007 | Image Comics | 9781582407234 | English | Fullerton, United States Savage Dragon Archives: v. 1 PDF Book Preview — Savage Dragon Archives, Vol. Both the Graphic Fantasy and Megaton issues containing the Dragon have since been reprinted in high- quality editions. It's the kind of comic that fans of independent publishing and the experimental nature of that field will enjoy immensely. LJY rated it did not like it Oct 18, Other Editions 1. Wonder of wonders, Erik Larsen actually loves all the dumb crap that comes with superhero comics! Following an attack on the police station and the murder of Cyberface who is later resurrected , the Dragon led a SWAT team to finally take down the Overlord. Big, stupid, 90's fun. Don't miss out on these great deals. Now, years later, I've decided to read the series in its entirety in these inexpensive archive editions. Remove from wishlist. Despite being the founding member of the team, the Dragon spends little time as a member. While he was gone, the Vicious Circle had taken control of the city. No trivia or quizzes yet. Categories : Comics characters introduced in Image Comics superheroes Fictional police officers Works about dragons Image Comics titles Extraterrestrial superheroes Fictional characters with superhuman strength Fictional warlords Fictional characters with accelerated healing Characters created by Erik Larsen Comics adapted into television series Comics adapted into animated series. If you like comic books that don't take themselves too seriously, then this just may be for you. -

Savage Dragon: Warfare Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SAVAGE DRAGON: WARFARE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erik Larsen | 128 pages | 20 Jun 2017 | Image Comics | 9781534303638 | English | Fullerton, United States Savage Dragon: Warfare PDF Book Though he had only been semi-active before, the Dragon officially resigns from the S. Following this, the Dragon fights a Dr. In these appearances, the character of the Dragon remained basically the same as it had been in Graphic Fantasy , with a few details modified such as the inclusion of his wife, who was dead in his previous incarnation. The Fiend can possess living bodies, and his powers are fueled by the capacity for hate of those possessed. Richard Richards' office building. Read a little about our history. Thankfully, his healing factor would mend him back together, and eventually, he would take down the original Overlord in a particularly violent way as revenge. The collection featured stories by the four remaining Image founders Erik Larsen, Todd McFarlane , Marc Silvestri , and Jim Valentino returning to the characters they first created for the company. Initially debuting in a three-issue miniseries, the Savage Dragon comic book met with enough success to justify a monthly series, launched in After a number of serious incidents, including the murder of the superhero Mighty Man and the brutal mauling of SuperPatriot , Darling takes drastic action. As Erik Larsen is occasionally wont to do, Savage Dragon speeds things up—not in the breakneck, action-orgy kind of way that we saw last month, but in order to bring the story up-to-date, since it unfolds in real time and in a real-ish facsimile of the world. -

Moore Layout Original

Bibliography Within your dictionary, next to word “prolific” you’ll created with their respective co-creators/artists) printing of this issue was pulped by DC hierarchy find a photo of Alan Moore – who since his profes - because of a Marvel Co. feminine hygiene product ad. AMERICA’S BEST COMICS 64 PAGE GIANT – Tom sional writing debut in the late Seventies has written A few copies were saved from the company’s shred - Strong “Skull & Bones” – Art: H. Ramos & John hundreds of stories for a wide range of publications, der and are now costly collectibles) Totleben / “Jack B. Quick’s Amazing World of both in the United States and the UK, from child fare Science Part 1” – Art: Kevin Nowlan / Top Ten: THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN like Star Wars to more adult publications such as “Deadfellas” – Art: Zander Cannon / “The FIRST (Volume One) #6 – “6: The Day of Be With Us” & Knave . We’ve organized the entries by publishers and First American” – Art: Sergio Aragonés / “The “Chapter 6: Allan and the Sundered Veil’s The listed every relevant work (comics, prose, articles, League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen Game” – Art: Awakening” – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 1999 artwork, reviews, etc...) written by the author accord - Kevin O’Neill / Splash Brannigan: “Specters from ingly. You’ll also see that I’ve made an emphasis on THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN Projectors” – Art: Kyle Baker / Cobweb: “He Tied mentioning the title of all his penned stories because VOLUME 1 – Art: Kevin O’Neill – 2000 (Note: Me To a Buzzsaw (And It Felt Like a Kiss)” – Art: it is a pet peeve of mine when folks only remember Hardcover and softcover feature compilation of the Dame Darcy / “Jack B. -

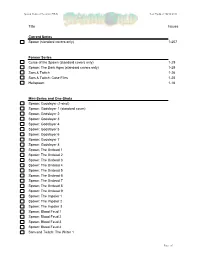

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA)

Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Title Issues Current Series Spawn (standard covers only) 1-207 Former Series Curse of the Spawn (standard covers only) 1-29 Spawn: The Dark Ages (standard covers only) 1-28 Sam & Twitch 1-26 Sam & Twitch: Case Files 1-25 Hellspawn 1-16 Mini-Series and One-Shots Spawn: Godslayer (1-shot) Spawn: Godslayer 1 (standard cover) Spawn: Godslayer 2 Spawn: Godslayer 3 Spawn: Godslayer 4 Spawn: Godslayer 5 Spawn: Godslayer 6 Spawn: Godslayer 7 Spawn: Godslayer 8 Spawn: The Undead 1 Spawn: The Undead 2 Spawn: The Undead 3 Spawn: The Undead 4 Spawn: The Undead 5 Spawn: The Undead 6 Spawn: The Undead 7 Spawn: The Undead 8 Spawn: The Undead 9 Spawn: The Impaler 1 Spawn: The Impaler 2 Spawn: The Impaler 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 1 Spawn: Blood Feud 2 Spawn: Blood Feud 3 Spawn: Blood Feud 4 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 1 Page of Spawn Comics Checklist (USA) Last Updated: 06/18/2011 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 2 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 3 Sam and Twitch: The Writer 4 Angela 1 Angela 2 Angela 3 Cy-Gor 1 Cy-Gor 2 Cy-Gor 3 Cy-Gor 4 Cy-Gor 5 Cy-Gor 6 Violator 1 Violator 2 Violator 3 Spawn: Blood & Shadows (Annual 1) Spawn Bible (1st Print) Spawn Bible (2nd Print) Spawn Bible (3rd Print) Spawn: Book of Souls Spawn: Blood & Salvation Spawn: Simony Spawn: Architects of Fear The Adventures of Spawn Director’s Cut The Adventures of Spawn 2 Celestine 1 (green) Celestine 1 (purple) Celestine 2 Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (1st Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) vol1 (2nd Print) Spawn Manga (Shadows of Spawn) -

Is Muhammad Also Among the Prophets?

Is Muhammad Also Among the Prophets? by Harley Talman he prophet Samuel had anointed Saul as king and predicted that the Spirit of the Lord would come upon him with power so that he would prophesy and be changed into a different person (1 Sam 10:6).T And thus it happened that “God changed Saul’s heart, and all these signs were fulfilled that day” and he prophesied (10:9,11). This was the last thing that people expected to happen to the “son of Kish.” As a result, “Is Saul also among the prophets?” became a proverb in Israel.1 The same Spirit later empowered him to defeat the Ammonites in battle (11:6). Yet this same Saul disobeyed God’s word and failed in his kingly office. It seems incredible that one endowed with the Spirit of God could act so con- trary to his will. God eventually rejected him as king, and withdrew his Spirit from him (16:1, 14). Saul persecuted David and repeatedly sought to kill him. The way that Saul’s life finished is so tragic that it dominates our memory of him; we forget that he had once been “among the prophets.” However, in recent years some biblical scholars have sought to restore bal- ance to our corporate memory of Saul. Seeking to rehabilitate his image, Ron Youngblood finds that despite his failings, Saul could also be “kind, thought- ful, generous, courageous, very much in control, and willing to obey God.”2 Is it advisable that Christians consider undertaking a similar project with the prophet of Islam? Can the malevolent image of Muhammad in our minds possibly be “rehabilitated”? As surprising as the idea may be, it is worth con- Harley Talman has worked with templating, since one of the most delicate issues we face in seeking construc- Muslims for 30 years, including two decades in the Arab world and Africa, tive dialogue with Muslims is our response to the question: “Is Muhammad during which he was involved in also among the prophets?” church planting, theological education, and humanitarian aid.