Brief History of the Bureau of Reclamation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

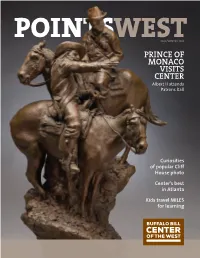

PRINCE of MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II Attends Patrons Ball

POINTSWEST fall/winter 2013 PRINCE OF MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II attends Patrons Ball Curiosities of popular Cliff House photo Center’s best in Atlanta Kids travel MILES for learning About the cover: Herb Mignery (b. 1937). On Common Ground, 2013. Bronze. Buffalo Bill and Prince Albert I of Monaco hunting together in 1913. Created by the artist for to the point HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco. BY BRUCE ELDREDGE | Executive Director ©2013 Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Points West is published for members and friends of the Center of the West. Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are Center of the West photos unless otherwise noted. Direct all questions about image rights and reproduction to [email protected]. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve space. However, such information is available by contacting the editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or [email protected]. ■ Managing Editor | Marguerite House ■ Assistant Editor | Nancy McClure ■ Designer | Desirée Pettet Continuity gives us roots; change gives us branches, ■ Contributing Staff Photographers | Mindy letting us stretch and grow and reach new heights. Besaw, Ashley Hlebinsky, Emily Wood, Nancy McClure, Bonnie Smith – pauline r. kezer, consultant ■ Historic Photographs/Rights and Reproductions | Sean Campbell like this quote because it describes so well our endeavor to change the look ■ Credits and Permissions | Ann Marie and feel of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West “brand.” On the one hand, Donoghue we’ve consciously kept a focus on William F. -

Elwood Mead: His Life and Legacy for Wyoming's Water Presentation

125 Years of Administering Wyoming’s Water By John Shields Interstate Streams Engineer Wyoming State Engineer’s Office Wyoming State Historical Society Member and 2007, 2009 & 2011 Homsher Endowment Grant Recipient June 26, 2013 Pathfinder Dam Spilling. Photograph taken in 1928. (Smaller sign below says: “Danger. Please hold on your children. This means y o u.” he Wyoming State Engineer’s Office takes this opportunity to again thank our sponsors whose contributions have allowed us to host yesterday’s tour and reception; and this evening’s reception. We greatly appreciate and gratefully acknowledge their financial support! Construction of the first railroad bridge over the Green River in 1868, Citadel Rock appearing prominently in the background Union Pacific's locomotive No. 3985 climbs Sherman Hill West of Cheyenne Wyoming Territory, about 1882. Detail from map of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming in People's Cyclopedia of Universal Knowledge (New York: Phillips & Hunt, 1882). Map from collection of Michael Cassity. Elwood Mead (1858-1936) was an engineer who pioneered western water law and worked tirelessly for over fifty years to ensure that water went to its best use. He was a preeminent champion of the conquest of arid America. Ever an idealist, Mead consistently held to his view of agrarian life based on individual farmers living on small irrigated plots. Mead’s career spanned irrigation’s history from 1880s corporate ditch enterprises in Colorado through the construction of Hoover Dam (and Lake Mead, named for him) a half century later. Elwood Mead while Wyoming State Engineer. Mead included in his 1889 Territorial Report to the Governor of Wyoming this drawing of the “Wyoming Nilometer.” The drawing includes an annotation: “Designed by Elwood Mead, Territorial Engineer.” • The Wyoming Constitutional Convention’s Committee on Irrigation and Water Rights’ report first reached the convention floor in Sept. -

Wraenews051.Pdf (1.529Mb)

12/2/2019 Preserving the Source – Colorado State University: Libraries LIBRARIES FIND SERVICES TECHNOLOGY ABOUT MY ACCOUNTS Colorado State University: Libraries > Find > Archives & Special Collections > Collections > Water Resources Archive > Preserving the Source PRESERVING THE SOURCE About - Water Resources Archive Finding Aids Digital Collections August 2019, issue #51 Research Guide Online exhibits BACK TO SCHOOL, BACK TO BASICS Donate With the start of school, it’s a good time to brush up on basics and boost your archival know-how. Whether you are a college or graduate student, or simply a student of life, gaining additional skill to find answers in archives can be What's New advantageous. To “prime the pump” (photo: pumping plant August - E-newsletter: south of Wiggins), we offer six tips to find answers in the Water Resources Archive. A bonus tip follows news Preserving the Source, Issue 51 about new videos we have online. August - New oral history interviews from Colorado water With the start of Colorado State University’s school year, we leaders embark on the institution’s sesquicentennial celebration. Because water-related education and research helped lay July - New finding aid: the foundation for what was then Colorado Agricultural Papers of William W. Sayre College, we’ll be highlighting that history here with our puzzler, as well as throughout the coming year. June - New finding aid: Records of the Arkansas Valley Sugar –Patty Rettig, Archivist, Water Resources Archive Beet and Irrigated Land Company SIGN UP FOR E-MAIL UPDATES! VISIT THE E-NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE TOP SIX TIPS TO FIND WATER HISTORY ANSWERS Most people don’t browse archives just for fun. -

C:\My Files\Papers\Julien & Meroney History

HISTORY of HYDRAULICS and FLUID MECHANICS at COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY Pierre Y. Julien 1 and Robert N. Meroney 2 presented at DARCY MEMORIAL SYMPOSIUM ON THE HISTORY OF HYDRAULICS World Water & Environmental Resources Congress 2003 June 23-26, Philadelphia, PA USA 1Borland Professor of Hydraulics 2Director Emeritus of the Fluid Mechanics and Wind Engineering Program Department of Civil Engineering Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523. 1 HISTORY of HYDRAULICS and FLUID MECHANICS at COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY Pierre Y. Julien 1 and Robert N. Meroney 2 In 1862, the United States Congress passed the Morrill Act granting land to each state in the amount of 30,000 acres for every senator and representative, thus Colorado received 90,000 acres. The receipts from the sale of this land were to form a perpetual fund with interest to support “at least one college to teach agriculture and the mechanic arts. Although the 1862 Act gave the state a grant of federal land for a college, it was not necessary to locate the college on the grant. In 1870 Governor Edward M. McCook signed the Territorial Bill establishing the Agricultural College of Colorado at Fort Collins. In November of 1874 the first small building, called the “claim shanty,” was completed. According to tradition, it was built in eight days in order to prevent the site of the college from being moved to some other town. It is known that both Greeley and Boulder were circulating petitions to get the college away from Fort Collins. Colorado was admitted to statehood in 1876, and the first State Legislature established the State Board of Agriculture in 1877, governing body for the agricultural college. -

Jabotinsky Wrecked Zionists' Hope for 'Water for Peace' in Mideast

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 29, Number 20, May 24, 2002 Jabotinsky Wrecked Zionists’ Hope For ‘Water for Peace’ in Mideast by Steven Meyer The first of a series of articles revealing how Vladimir Ze’ev neer for the construction of the colossal Hoover Dam project Jabotinsky, the factional sympathizer of Mussolini and Hitler in the United States, and its man-made lake is named in his in the Zionist movement, was used by the British oligarchy to honor. prevent the creation of independent, industrially and scien- Mead’s initial report suggested that using his techniques, tifically developed states in the Middle East. The Likud Prime Palestine could become as verdant as Southern California, Ministers known as Jabotinsky’s “Princes” have brought the and that the Jordan Valley, like the Imperial Valley in Califor- Middle East to the brink of general religious war. nia, had the capacity “to supply distant cities with fruits and vegetables.” Mead’s projects included the building of a dam In 1976, economist and Presidential candidate Lyndon in the upper Jordan Valley that would “light cities, turn the LaRouche issued a policy statement, known as the Oasis Plan, wheels of factories, pump water for irrigation, and give to the which would establish a Middle East peace to “make the de- country a varied and prosperous industrial life.” serts bloom.” LaRouche’s policy was that a durable peace The following year, Meade became the Commissioner of could be established only through economic cooperation be- the U.S. Bureau of Land Reclamation, a position he occupied tween Israel and her Arab neighbors. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

ELWOOD MEAD: IRRIGATION ENGINEER AND SOCIAL PLANNER Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kluger, James R. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 10:58:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290253 71-8429 KLUGER, James Robert, 1939- ELWOOD MEAD: IRRIGATION ENGINEER AND SOCIAL PLANNER. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1970 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED ELWOOD MEAD: IRRIGATION ENGINEER AND SOCIAL PLANNER by James Robert Kluger r A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 7 0 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by James Robert KLuger entitled Elwood Mead: Irrigation Engineer and Social Planner be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the Doctor of Philosophy degree of ^ /, 1970 Dissertation Director Date\J After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:*" ^ Ow, S, /fro "This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. -

Hoover Dam: Scientific Studies, Name Controversy, Tourist Attraction, and Contributions to Engineering

Hoover Dam: Scientific Studies, Name Controversy, Tourist Attraction, and Contributions to Engineering J. David Rogers1, Ph.D., P.E., P.G., F. ASCE 1K.F. Hasslemann Chair in Geological Engineering, Missouri University of Science & Technology, Rolla, MO 65409; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Hoover Dam was a monumental accomplishment for its era which set new standards for post-construction performance evaluations. Many landmark studies were undertaken as part of the Boulder Canyon project which shaped the future of dam building. Some of these included: comprehensive surveys of reservoir sedimentation, which continue to the present; the discovery of turbidity currents operating in Lake Mead; the nature of nutrient-rich sediment contained in these density currents; cooperative studies of crustal deflection beneath the weight of Lake Mead; and reservoir-triggered seismicity. These studies were of great import in evaluating the impacts of large dams and reservoirs, world-wide, and have led to a much better understanding of reservoir siltation than previously existed. Hoover Dam was also the first dam to be fitted with strong motion accelerometers and Lake Mead the first reservoir to have an array of seismographs to evaluate the impacts of reservoir triggered seismicity. Along the way, there has been considerable confusion about the name of the dam, which was changed in 1931, 1933, and 1947. Most of the project documents are filed or referred to by the several names employed by Reclamation between 1928-1947. The article concludes with a brief description of the Boulder Canyon Project Reports, which have been translated into many different languages and distributed world-wide. -

Elwood Mead on Water Administration in Wyoming and the West

THE WYOMING STATE ENGINEER’S OFFICE AND THE WYOMING WATER ASSOCIATION UPON THE OCCASION OF THE WYOMING WATER ASSOCIATION’S WYOMING WATER 2000 NOVEMBER 1ST THROUGH 3RD ANNUAL MEETING AND EDUCATIONAL SEMINAR HAVE APPRECIATIVELY COMPILED: SELECTED WRITINGS OF ELWOOD MEAD ON WATER ADMINISTRATION IN WYOMING AND THE WEST FOREWORD Elwood Mead (1858-1936) was a fascinating man who, as stated by his biographer, worked tirelessly for over fifty years to ensure that water went to its best use. Here in Wyoming, many people have heard of him and are aware that he wrote our water laws, and that those laws have changed very little since the time of Statehood. Like George Washington, the "father of our country," and a man about whom the average American can recite but a few things learned back in grade school, very little is generally known by the citizens of Wyoming about Elwood Mead - beyond the fact that he may be considered the "father" of the water law that has worked so well for over 100 years for our State. Yet this is not altogether surprising, for the allocation and distribution of water is, in many ways, a complicated subject. So too, was Elwood Mead. We intend this booklet to add to both your understanding of Engineer Mead and of the water administration system that he developed and that continues to be used, every day, across this State. In the preface to his book, Turning on Water With a Shovel, the Career of Elwood Mead, author James Kluger observed “[l]inked as it is to environmental issues and recent droughts, water has become a major contemporary concern and a hot topic for historians.” Prior to and at the time of Statehood for Wyoming, surely the matter of water allocation was a contemporary concern as evidenced in these compiled writings by Mead. -

Constructing a River, Building a Border: an Environmental History of Irrigation, Water Law, State Formation, and the Rio Grande

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2016-01-01 Constructing a River, Building a Border: An Environmental History of Irrigation, Water Law, State Formation, and the Rio Grande Rectification Project in the El Paso/Juárez Valley Joanne Kropp University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, History Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kropp, Joanne, "Constructing a River, Building a Border: An Environmental History of Irrigation, Water Law, State Formation, and the Rio Grande Rectification Project in the El Paso/Juárez Valley" (2016). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 678. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/678 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTING A RIVER, BUILDING A BORDER: AN ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF IRRIGATION, WATER LAW, STATE FORMATION, AND THE RIO GRANDE RECTIFICATION PROJECT IN THE EL PASO/JUÁREZ VALLEY JOANNE TORTORETE KROPP Doctoral Program in Borderlands History APPROVED: Samuel Brunk, Ph.D., Chair Jeffery P. Shepherd, Ph.D. Ann R. Gabbert, Ph.D Timothy Collins, Ph.D. Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Joanne Tortorete Kropp 2016 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family and friends. I could never have completed this work without the constant support and encouragement provided by my wonderful husband, my amazing children, and my beautiful grandchildren. -

Historic and Future Challenges in Western Water Law: the Case of Wyoming

Wyoming Law Review Volume 6 Number 2 Article 2 January 2006 Historic and Future Challenges in Western Water Law: The Case of Wyoming Anne MacKinnon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlr Recommended Citation MacKinnon, Anne (2006) "Historic and Future Challenges in Western Water Law: The Case of Wyoming," Wyoming Law Review: Vol. 6 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlr/vol6/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wyoming Law Review by an authorized editor of Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. MacKinnon: Historic and Future Challenges in Western Water Law: The Case of WYOMING LAW REVIEW VOLUME 6 2006 NUMBER 2 HISTORIC AND FUTURE CHALLENGES IN WESTERN WATER LAW: THE CASE OF WYOMING Anne MacKinnon* INTROD UCTION ............................................................................................ 291 I. Order Out of Chaos ........................................................................ 295 H. Evolution under Pressure............................................................... 309 III. The Danger of Becoming Irrelevant............................................... 321 IV . Next Steps in Evolution ................................................................... 328 INTRODUCTION It was as a reporter for the Casper Star-Tribune in the 1980s that I was first struck by the "Culture of Water" in Wyoming-in two ways. First, there was the hushed silence that -

Elwood Mead Papers, 1900-1942

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf629005xc No online items Inventory of the Elwood Mead Papers, 1900-1942 Processed by the Water Resources Collections and Archives staff. Water Resources Collections and Archives Orbach Science Library, Room 118 PO Box 5900 University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Phone: (951) 827-2934 Fax: (951) 827-6378 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/wrca © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Elwood Mead MEAD 1 Papers, 1900-1942 Inventory of the Elwood Mead Papers, 1900-1942 Collection number: MEAD Water Resources Collections and Archives University of California, Riverside Riverside, California Contact Information: Water Resources Collections and Archives Orbach Science Library, Room 118 PO Box 5900 University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Phone: (951) 827-2934 Fax: (951) 827-6378 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/wrca Processed by: Water Resources Collections and Archives staff Date Completed: February 1993 © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Elwood Mead Papers, Date (inclusive): 1900-1942 Collection number: MEAD Creator: Mead, Elwood, 1858-1936 Extent: ca. 2 linear ft. (4 boxes) Repository: Water Resources Collections and Archives Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Shelf location: Water Resources Collections and Archives. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Water Resources Collections and Archives. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Archives. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Water Resources Collections and Archives as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained by the reader. -

Elwood Mead Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf629005xc No online items Elwood Mead papers Finding aid prepared by Water Resources Collections and Archives staff. Special Collections & University Archives The UCR Library P.O. Box 5900 University of California Riverside, California 92517-5900 Phone: 951-827-3233 Fax: 951-827-4673 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/libraries/special-collections-university-archives © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Elwood Mead papers WRCA 055 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Elwood Mead papers Date (inclusive): 1900-1942 Collection Number: WRCA 055 Creator: Mead, Elwood, 1858-1936 Extent: 1.67 linear feet(4 boxes) Repository: Rivera Library. Special Collections Department. Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Abstract: The collection consists of correspondence, addresses, reports, and press releases on land settlement and irrigation projects in the Western States, Australia, and Mexico. Languages: The collection is in English. Access The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the University of California, Riverside Libraries, Special Collections & University Archives. Distribution or reproduction of materials protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written permission of the copyright owners. To the extent other restrictions apply, permission for distribution or reproduction from the applicable rights holder is also required. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user Preferred Citation [identification of item], [date if possible]. Elwood Mead papers (WRCA 055). Water Resources Collections and Archives. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside. Acquisition Information Provenance unknown Processing History Processed by Water Resources Collections and Archives staff, 1999.