University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRINCE of MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II Attends Patrons Ball

POINTSWEST fall/winter 2013 PRINCE OF MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II attends Patrons Ball Curiosities of popular Cliff House photo Center’s best in Atlanta Kids travel MILES for learning About the cover: Herb Mignery (b. 1937). On Common Ground, 2013. Bronze. Buffalo Bill and Prince Albert I of Monaco hunting together in 1913. Created by the artist for to the point HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco. BY BRUCE ELDREDGE | Executive Director ©2013 Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Points West is published for members and friends of the Center of the West. Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are Center of the West photos unless otherwise noted. Direct all questions about image rights and reproduction to [email protected]. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve space. However, such information is available by contacting the editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or [email protected]. ■ Managing Editor | Marguerite House ■ Assistant Editor | Nancy McClure ■ Designer | Desirée Pettet Continuity gives us roots; change gives us branches, ■ Contributing Staff Photographers | Mindy letting us stretch and grow and reach new heights. Besaw, Ashley Hlebinsky, Emily Wood, Nancy McClure, Bonnie Smith – pauline r. kezer, consultant ■ Historic Photographs/Rights and Reproductions | Sean Campbell like this quote because it describes so well our endeavor to change the look ■ Credits and Permissions | Ann Marie and feel of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West “brand.” On the one hand, Donoghue we’ve consciously kept a focus on William F. -

Brief History of the Bureau of Reclamation

Brief History of The Bureau of Reclamation 2 Glen Canyon Under Construction Colorado River Storage Project - April 9, 1965 Photographer - unknown Bureau of Reclamation History Program THE MOVEMENT FOR RECLAMATION Only about 2.6 percent of the earth's water supply is fresh, and some two-thirds of that is frozen in icecaps and glaciers or locked up in some other form such as moisture in the atmosphere or groundwater. That leaves less than eight-tenths of 1 percent of the earth’s water, about 30 percent of fresh water, available for humankind’s use. The largely arid American West receives a distinctly small share of that available supply of fresh water. As a result, water is a dominating factor in the arid West’s prehistory and history because it is required for occupation, settlement, agriculture, and industry. The snowmelt and gush of spring and early summer runoff frustrated early Western settlers. They watched helplessly as water they wanted to use in the dry days of late summer disappeared down Western watercourses. Settlers responded by developing water projects and creating complicated Western water law systems, which varied in detail among the various states and territories but generally allocated property rights in available water based on the concept of prior appropriation (first in time, first in right) for beneficial use. At first, water development projects were simple. Settlers diverted water from a stream or river and used it nearby; but, in many areas, the demand for water outstripped the supply. As demands for water increased, settlers wanted to store "wasted" runoff for later use. -

Elwood Mead: His Life and Legacy for Wyoming's Water Presentation

125 Years of Administering Wyoming’s Water By John Shields Interstate Streams Engineer Wyoming State Engineer’s Office Wyoming State Historical Society Member and 2007, 2009 & 2011 Homsher Endowment Grant Recipient June 26, 2013 Pathfinder Dam Spilling. Photograph taken in 1928. (Smaller sign below says: “Danger. Please hold on your children. This means y o u.” he Wyoming State Engineer’s Office takes this opportunity to again thank our sponsors whose contributions have allowed us to host yesterday’s tour and reception; and this evening’s reception. We greatly appreciate and gratefully acknowledge their financial support! Construction of the first railroad bridge over the Green River in 1868, Citadel Rock appearing prominently in the background Union Pacific's locomotive No. 3985 climbs Sherman Hill West of Cheyenne Wyoming Territory, about 1882. Detail from map of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming in People's Cyclopedia of Universal Knowledge (New York: Phillips & Hunt, 1882). Map from collection of Michael Cassity. Elwood Mead (1858-1936) was an engineer who pioneered western water law and worked tirelessly for over fifty years to ensure that water went to its best use. He was a preeminent champion of the conquest of arid America. Ever an idealist, Mead consistently held to his view of agrarian life based on individual farmers living on small irrigated plots. Mead’s career spanned irrigation’s history from 1880s corporate ditch enterprises in Colorado through the construction of Hoover Dam (and Lake Mead, named for him) a half century later. Elwood Mead while Wyoming State Engineer. Mead included in his 1889 Territorial Report to the Governor of Wyoming this drawing of the “Wyoming Nilometer.” The drawing includes an annotation: “Designed by Elwood Mead, Territorial Engineer.” • The Wyoming Constitutional Convention’s Committee on Irrigation and Water Rights’ report first reached the convention floor in Sept. -

NORMAN K Denzin Sacagawea's Nickname1, Or the Sacagawea

NORMAN K DENZIN Sacagawea’s Nickname1, or The Sacagawea Problem The tropical emotion that has created a legendary Sacajawea awaits study...Few others have had so much sentimental fantasy expended on them. A good many men who have written about her...have obviously fallen in love with her. Almost every woman who has written about her has become Sacajawea in her inner reverie (DeVoto, 195, p. 618; see also Waldo, 1978, p. xii). Anyway, what it all comes down to is this: the story of Sacagawea...can be told a lot of different ways (Allen, 1984, p. 4). Many millions of Native American women have lived and died...and yet, until quite recently, only two – Pocahantas and Sacagawea – have left even faint tracings of their personalities on history (McMurtry, 001, p. 155). PROLOGUE 1 THE CAMERA EYE (1) 2: Introduction: Voice 1: Narrator-as-Dramatist This essay3 is a co-performance text, a four-act play – with act one and four presented here – that builds on and extends the performance texts presented in Denzin (004, 005).4 “Sacagawea’s Nickname, or the Sacagawea Problem” enacts a critical cultural politics concerning Native American women and their presence in the Lewis and Clark Journals. It is another telling of how critical race theory and critical pedagogy meet popular history. The revisionist history at hand is the history of Sacagawea and the representation of Native American women in two cultural and symbolic landscapes: the expedition journals, and Montana’s most famous novel, A B Guthrie, Jr.’s mid-century novel (1947), Big Sky (Blew, 1988, p. -

Nebraska's Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World Full Citation: William E Deahl Jr, “Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World,” Nebraska History 49 (1968): 282-297 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1968Entertainment.pdf Date: 11/23/2015 Article Summary: Buffalo Bill Cody and Dr. W F Carver were not the first to mount a Wild West show, but their opening performances in 1883 were the first truly successful entertainments of that type. Their varied acts attracted audiences familiar with Cody and his adventures. Cataloging Information: Names: William F Cody, W F Carver, James Butler Hickok, P T Barnum, Sidney Barnett, Ned Buntline (Edward Zane Carroll Judson), Joseph G McCoy, Nate Salsbury, Frank North, A H Bogardus Nebraska Place Names: Omaha Wild West Shows: Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition -

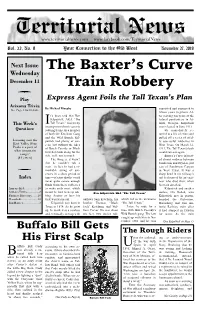

The Baxter's Curve Train Robbery

Territorial News www.territorialnews.com www.facebook.com/TerritorialNews Vol. 33, No. 9 Your Connection to the Old West November 27, 2019 Next Issue The Baxter’s Curve Wednesday December 11 Train Robbery Play Express Agent Foils the Tall Texan’s Plan Arizona Trivia By Michael Murphy convicted and sentenced to See Page 2 for Details fifteen years in prison. Af- t’s been said that Ben ter serving ten years at the Kilpatrick, AKA “The federal penitentiary in At- This Week’s I Tall Texan,” was pretty lanta, Georgia, Kilpatrick incompetent when it came to was released in June 1911. Question: robbing trains. As a member He immediately re- of both the Ketchum Gang turned to a life of crime and and the Wild Bunch, Kil- pulled off a series of mild- Looming over the patrick had plenty of suc- ly successful robberies in East Valley, Four cess, but without the likes West Texas. On March 12, Peaks is a part of of Butch Cassidy or Black 1912, The Tall Texan’s luck what mountain Jack Ketchum along for the would run out again. range? ride, well, not so much. Baxter’s Curve is locat- (8 Letters) The thing is, it wasn’t ed almost midway between that he couldn’t rob a Sanderson and Dryden, just train—in fact he had a re- east of Sanderson Canyon markable string of suc- in West Texas. It was a cesses in a short period of sharp bend in the railway’s Index time—it’s just that he could rail bed named for an engi- never quite secure enough neer who died there when funds from these robberies his train derailed. -

Calamity Jane

Calamity Jane Calamity Jane was born on May 1, 1852 in Princeton, Missouri. Her real name was Martha Jane Cannary. By the time she was 12 years old, both of her parents had died. It was then her job to raise her 5 younger brothers and sisters. She moved the family from Missouri to Wyoming and did whatever she could to take care of her brothers and sisters. In 1876, Calamity Jane settled in Deadwood, South Dakota, the site of a new gold rush. It has been told that during this time she met Wild Bill Hickok, who was known for his shooting skills. Jane would later say that she married him in 1873. Many people think this was not true because if you look at the years, she said she married him 3 years before she really met him. When she was in Deadwood, Jane carried goods and machinery to camps outside of the town and worked other jobs too. She was known for being loud and annoying. She also did not act very lady like. However, she was known to be very generous and giving. Jane worked as a cook, a nurse, a miner and an ox-team driver, and became an excellent horseback rider who was great with a gun. She was a good shot and a fearless rider for a girl her age. By 1893, Calamity Jane was appearing in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show as a trick shooter and horse rider. She died on August 1, 1903, in Terry, South Dakota, at the age of 51. -

Wild West Photograph Collection

THE KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY Wild West Photograph Collection This collection of images primarily relates to Western lore during the late 19th and parts of the 20th centuries. It includes cowboys and cowgirls, entertainment figures, venues as rodeos and Wild West shows, Indians, lawmen, outlaws and their gangs, as well as criminals including those involved in the Union Station Massacre. Descriptive Summary Creator: Brookings Montgomery Title: Wild West Photograph Collection Dates: circa 1880s-1960s Size: 4 boxes, 1 3/4 cubic feet Location: P2 Administrative Information Restriction on access: Unrestricted Terms governing use and reproduction: Most of the photographs in the collection are reproductions done by Mr. Montgomery of originals and copyright may be a factor in their use. Additional physical form available: Some of the photographs are available digitally from the library's website. Location of originals: Location of original photographs used by photographer for reproduction is unknown. Related sources and collections in other repositories: Ralph R. Doubleday Rodeo Photographs, Donald C. & Elizabeth Dickinson Research center, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. See also "Ikua Purdy, Yakima Canutt, and Pete Knight: Frontier Traditions Among Pacific Basin Rodeo Cowboys, 1908-1937," Journal of the West, Vol. 45, No.2, Spring, 2006, p. 43-50. (Both Canutt and Knight are included in the collection inventory list.) Acquisition information: Primarily a purchase, circa 1960s. Citation note: Wild West Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri. Collection Description Biographical/historical note The Missouri Valley Room was established in 1960 after the Kansas City Public Library moved into its then new location at 12th and Oak in downtown Kansas City. -

Frederick Jackson Turner and Buffalo Bill Richard White

Frederick Jackson Turner and Buffalo Bill Richard White Americans have never had much use for history, but we do like anniversaries. In 1893 Frederick Jackson Turner, who would become the most eminent historian of his generation, was in Chicago to deliver an academic paper at the historical congress convened in conjunction with the Columbian Exposition. The occasion for the exposition was a slightly belated celebration of the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus's arrival in the Western Hemisphere. The paper Turner presented was "The Significance of the Frontier in American History." 1 Although public anniversaries often have educational pretensions, they are primarily popular entertainments; it is the combination of the popular and the educational that makes the figurative meeting of Buffalo Bill and Turner at the Columbian Exposition so suggestive. Chicago celebrated its own progress from frontier beginnings. While Turner gave his academic talk on the frontier, Buffalo Bill played, twice a day, "every day, rain or shine," at "63rd St—Opposite the World's Fair," before a covered grandstand that could hold eighteen thousand people.2 Turner was an educator, an academic, but he had also achieved great popular success because of his mastery of popular frontier iconography. Buffalo Bill was a showman (though he never referred to his Wild West as a show) with educational pretensions. Characteristically, his program in 1893 bore the title Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World (Figure 1).3 In one of the numerous endorsements reproduced in the program, a well-known midwestern journalist, Brick Pomeroy, proclaimed the exhibition a ''Wild West Reality . -

Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press Fall 2010 Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill Charles Eldridge Griffin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Griffin, Charles Eldridge, our"F Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill" (2010). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 47. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill Buy the Book series editor D. Kurt Graham Buy the Book charles eldridge griffin Four Years in Europe with Buffalo Bill Edited and with an introduction by Chris Dixon University of Nebraska Press Lincoln & London Buy the Book Support for this volume was provided by a generous gift from The Dellenback Family Foundation. © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America All images courtesy the Buffalo Bill Historical Center. Support for the printing of this volume was provided by Jack and Elaine Rosenthal. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Griffi n, Charles Eldridge. Four years in Europe with Buffalo Bill / Charles Eldridge Griffi n; edited and with an introduction by Chris Dixon. p. -

Wild West Canada: Buffalo Bill and Transborder History

Wild West Canada: Buffalo Bill and Transborder History A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon Adam Grieve Copyright Adam Grieve, April, 2016. All Rights Reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Abstract Canadians continue to struggle with their western identity. For one reason or another, they have separated themselves from an Americanized “blood and thunder” history. -

Concordia Cemetery and the Power Over Space, 1800-1895 Nancy Gonzalez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2014-01-01 Reinventing the Old West: Concordia Cemetery and the Power Over Space, 1800-1895 Nancy Gonzalez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Chicana/o Studies Commons, History Commons, Latina/o Studies Commons, and the Other International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzalez, Nancy, "Reinventing the Old West: Concordia Cemetery and the Power Over Space, 1800-1895" (2014). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1630. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1630 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REINVENTING THE OLD WEST: CONCORDIA CEMETERY AND THE POWER OVER SPACE, 1800-1895 NANCY GONZALEZ Department of History APPROVED: Yolanda Chavez Leyva, Ph.D., Chair Jeffrey Shepherd, Ph.D. Maceo C. Dailey, Ph.D. Dennis Bixler Marquez, Ph.D. Bess Sirmon-Taylor, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Nancy Gonzalez 2014 Dedication I dedicate this work to my parents Salvador Gonzalez+ and Nieves T. Gonzalez, to my siblings Juan, Gloria Velia, Sal and Ray and to my good friend Joseph Michael Cascio+ REINVENTING THE OLD WEST: CONCORDIA CEMETERY AND THE POWER OVER SPACE, 1800-1895 by NANCY GONZALEZ, M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2014 Acknowledgements I am very fortunate to have received so much support in writing this dissertation.