Charles A. Lory Papers (Fort Collins: Colorado State University Libraries, 1979, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

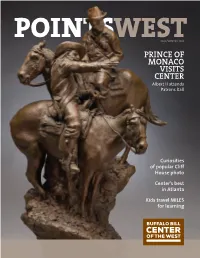

PRINCE of MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II Attends Patrons Ball

POINTSWEST fall/winter 2013 PRINCE OF MONACO VISITS CENTER Albert II attends Patrons Ball Curiosities of popular Cliff House photo Center’s best in Atlanta Kids travel MILES for learning About the cover: Herb Mignery (b. 1937). On Common Ground, 2013. Bronze. Buffalo Bill and Prince Albert I of Monaco hunting together in 1913. Created by the artist for to the point HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco. BY BRUCE ELDREDGE | Executive Director ©2013 Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Points West is published for members and friends of the Center of the West. Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are Center of the West photos unless otherwise noted. Direct all questions about image rights and reproduction to [email protected]. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve space. However, such information is available by contacting the editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or [email protected]. ■ Managing Editor | Marguerite House ■ Assistant Editor | Nancy McClure ■ Designer | Desirée Pettet Continuity gives us roots; change gives us branches, ■ Contributing Staff Photographers | Mindy letting us stretch and grow and reach new heights. Besaw, Ashley Hlebinsky, Emily Wood, Nancy McClure, Bonnie Smith – pauline r. kezer, consultant ■ Historic Photographs/Rights and Reproductions | Sean Campbell like this quote because it describes so well our endeavor to change the look ■ Credits and Permissions | Ann Marie and feel of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West “brand.” On the one hand, Donoghue we’ve consciously kept a focus on William F. -

Brief History of the Bureau of Reclamation

Brief History of The Bureau of Reclamation 2 Glen Canyon Under Construction Colorado River Storage Project - April 9, 1965 Photographer - unknown Bureau of Reclamation History Program THE MOVEMENT FOR RECLAMATION Only about 2.6 percent of the earth's water supply is fresh, and some two-thirds of that is frozen in icecaps and glaciers or locked up in some other form such as moisture in the atmosphere or groundwater. That leaves less than eight-tenths of 1 percent of the earth’s water, about 30 percent of fresh water, available for humankind’s use. The largely arid American West receives a distinctly small share of that available supply of fresh water. As a result, water is a dominating factor in the arid West’s prehistory and history because it is required for occupation, settlement, agriculture, and industry. The snowmelt and gush of spring and early summer runoff frustrated early Western settlers. They watched helplessly as water they wanted to use in the dry days of late summer disappeared down Western watercourses. Settlers responded by developing water projects and creating complicated Western water law systems, which varied in detail among the various states and territories but generally allocated property rights in available water based on the concept of prior appropriation (first in time, first in right) for beneficial use. At first, water development projects were simple. Settlers diverted water from a stream or river and used it nearby; but, in many areas, the demand for water outstripped the supply. As demands for water increased, settlers wanted to store "wasted" runoff for later use. -

Elwood Mead: His Life and Legacy for Wyoming's Water Presentation

125 Years of Administering Wyoming’s Water By John Shields Interstate Streams Engineer Wyoming State Engineer’s Office Wyoming State Historical Society Member and 2007, 2009 & 2011 Homsher Endowment Grant Recipient June 26, 2013 Pathfinder Dam Spilling. Photograph taken in 1928. (Smaller sign below says: “Danger. Please hold on your children. This means y o u.” he Wyoming State Engineer’s Office takes this opportunity to again thank our sponsors whose contributions have allowed us to host yesterday’s tour and reception; and this evening’s reception. We greatly appreciate and gratefully acknowledge their financial support! Construction of the first railroad bridge over the Green River in 1868, Citadel Rock appearing prominently in the background Union Pacific's locomotive No. 3985 climbs Sherman Hill West of Cheyenne Wyoming Territory, about 1882. Detail from map of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming in People's Cyclopedia of Universal Knowledge (New York: Phillips & Hunt, 1882). Map from collection of Michael Cassity. Elwood Mead (1858-1936) was an engineer who pioneered western water law and worked tirelessly for over fifty years to ensure that water went to its best use. He was a preeminent champion of the conquest of arid America. Ever an idealist, Mead consistently held to his view of agrarian life based on individual farmers living on small irrigated plots. Mead’s career spanned irrigation’s history from 1880s corporate ditch enterprises in Colorado through the construction of Hoover Dam (and Lake Mead, named for him) a half century later. Elwood Mead while Wyoming State Engineer. Mead included in his 1889 Territorial Report to the Governor of Wyoming this drawing of the “Wyoming Nilometer.” The drawing includes an annotation: “Designed by Elwood Mead, Territorial Engineer.” • The Wyoming Constitutional Convention’s Committee on Irrigation and Water Rights’ report first reached the convention floor in Sept. -

Broadway East (Running North and South)

ROTATION OF DENVER STREETS (with Meaning) The following information was obtained and re-organized from the book; Denver Streets: Names, Numbers, Locations, Logic by Phil H. Goodstein This book includes additional information on how the grid came together. Please email [email protected] with any corrections/additions found. Copy: 12-29-2016 Running East & West from Broadway South Early businessman who homesteaded West of Broadway and South of University of Denver Institutes of Higher Learning First Avenue. 2000 ASBURY AVE. 50 ARCHER PL. 2100 EVANS AVE.` 2700 YALE AVE. 100 BAYAUD AVE. 2200 WARREN AVE. 2800 AMHERST AVE. 150 MAPLE AVE. 2300 ILIFF AVE. 2900 BATES AVE. 200 CEDAR AVE. 2400 WESLEY AVE. 3000 CORNELL AVE. 250 BYERS PL. 2500 HARVARD AVE. 3100 DARTMOUTH 300 ALAMEDA AVE. 2600 VASSAR AVE. 3200 EASTMAN AVE. 3300 FLOYD AVE. 3400 GIRARD AVE. Alameda Avenue marked the city 3500 HAMPDEN AVE. limit until the town of South 3600 JEFFERSON AVE. Denver was annexed in 3700 KENYON AVE. 1894. Many of the town’s east- 3800 LEHIGH AVE. west avenues were named after 3900 MANSFIELD AVE. American states and 4000 NASSAU AVE. territories, though without any 4100 OXFORD AVE. clear pattern. 4200 PRINCETON AVE. 350 NEVADA PL. 4300 QUINCY AVE. 400 DAKOTA AVE. 4400 RADCLIFF AVE. 450 ALASKA PL. 4500 STANFORD AVE. 500 VIRGINIA AVE. 4600 TUFTS AVE. 600 CENTER AVE. 4700 UNION AVE. 700 EXPOSITION AVE. 800 OHIO AVE. 900 KENTUCKY AVE As the city expanded southward some 1000 TENNESSEE AVE. of the alphabetical system 1100 MISSISSIPPI AVE. disappeared in favor 1200 ARIZONA AVE. -

Wraenews051.Pdf (1.529Mb)

12/2/2019 Preserving the Source – Colorado State University: Libraries LIBRARIES FIND SERVICES TECHNOLOGY ABOUT MY ACCOUNTS Colorado State University: Libraries > Find > Archives & Special Collections > Collections > Water Resources Archive > Preserving the Source PRESERVING THE SOURCE About - Water Resources Archive Finding Aids Digital Collections August 2019, issue #51 Research Guide Online exhibits BACK TO SCHOOL, BACK TO BASICS Donate With the start of school, it’s a good time to brush up on basics and boost your archival know-how. Whether you are a college or graduate student, or simply a student of life, gaining additional skill to find answers in archives can be What's New advantageous. To “prime the pump” (photo: pumping plant August - E-newsletter: south of Wiggins), we offer six tips to find answers in the Water Resources Archive. A bonus tip follows news Preserving the Source, Issue 51 about new videos we have online. August - New oral history interviews from Colorado water With the start of Colorado State University’s school year, we leaders embark on the institution’s sesquicentennial celebration. Because water-related education and research helped lay July - New finding aid: the foundation for what was then Colorado Agricultural Papers of William W. Sayre College, we’ll be highlighting that history here with our puzzler, as well as throughout the coming year. June - New finding aid: Records of the Arkansas Valley Sugar –Patty Rettig, Archivist, Water Resources Archive Beet and Irrigated Land Company SIGN UP FOR E-MAIL UPDATES! VISIT THE E-NEWSLETTER ARCHIVE TOP SIX TIPS TO FIND WATER HISTORY ANSWERS Most people don’t browse archives just for fun. -

C:\My Files\Papers\Julien & Meroney History

HISTORY of HYDRAULICS and FLUID MECHANICS at COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY Pierre Y. Julien 1 and Robert N. Meroney 2 presented at DARCY MEMORIAL SYMPOSIUM ON THE HISTORY OF HYDRAULICS World Water & Environmental Resources Congress 2003 June 23-26, Philadelphia, PA USA 1Borland Professor of Hydraulics 2Director Emeritus of the Fluid Mechanics and Wind Engineering Program Department of Civil Engineering Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523. 1 HISTORY of HYDRAULICS and FLUID MECHANICS at COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY Pierre Y. Julien 1 and Robert N. Meroney 2 In 1862, the United States Congress passed the Morrill Act granting land to each state in the amount of 30,000 acres for every senator and representative, thus Colorado received 90,000 acres. The receipts from the sale of this land were to form a perpetual fund with interest to support “at least one college to teach agriculture and the mechanic arts. Although the 1862 Act gave the state a grant of federal land for a college, it was not necessary to locate the college on the grant. In 1870 Governor Edward M. McCook signed the Territorial Bill establishing the Agricultural College of Colorado at Fort Collins. In November of 1874 the first small building, called the “claim shanty,” was completed. According to tradition, it was built in eight days in order to prevent the site of the college from being moved to some other town. It is known that both Greeley and Boulder were circulating petitions to get the college away from Fort Collins. Colorado was admitted to statehood in 1876, and the first State Legislature established the State Board of Agriculture in 1877, governing body for the agricultural college. -

Colorado Governors Teller Ammons

Colorado Governors Teller Ammons Scope and Content Note The Teller Ammons collection comprises approximately 21 cubic feet of record material spanning his term from 1937-1939. Major record series included in the collection are correspondence; miscellaneous; reports; petitions; Executive Record; Budget & Efficiency Investigations 1938; and speeches and messages. The correspondence series makes up the bulk of the collection and is organized by subject or correspondent. Strengths of the collection include documentation concerning water rights controversies, federal programs instituted to fight the poverty created by the Great Depression, and Ammons' efforts to make the state more financially sound and efficient. Biography of Teller Ammons Teller Ammons was one of the youngest men ever to become governor of Colorado. He was elected shortly before his fortieth birthday in 1936. Teller was the son of former Governor Ellias M. Ammons, who served as the state's chief executive from 1912 to 19 14. Ammons was born in Denver on December 3, 1895, and was named after his father's friend, U.S. Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado. His family moved to Colorado in 1871, five years before the territory became a state. He received his early educatio n in Douglas County rural schools where he lived on his father's cattle ranch. He then moved to Denver and graduated from North High School. Ammons later served in the U.S. Army in France for two years during World War I. After the war, he homesteaded on a ranch in Grand County but returned to Denver in 1923, where he went to work for a newspaper. -

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc. Visual Materials BIOGRAPHY A Abeyta family Abbott, Emma Abbott, Hellen Abbott, Stephen S. Abernathy, Ralph (Rev.) Abot, Bessie SEE: Oversize photographs Abreu, Charles Acheson, Dean Gooderham Acker, Henry L. Adair, Alexander Adami, Charles and family Adams, Alva (Gov.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) (Adams, Elizabeth Matty) Adams, Alva Blanchard Jr. Adams, Andy Adams, Charles Adams, Charles Partridge Adams, Frederick Atherton and family Adams, George H. Adams, James Capen (“Grizzly”) Adams, James H. and family Adams, John T. Adams, Johnnie Adams, Jose Pierre Adams, Louise T. Adams, Mary Adams, Matt Adams, Robert Perry Adams, Mrs. Roy (“Brownie”) Adams, W. H. SEE ALSO: Oversize photographs Adams, William Herbert and family Addington, March and family Adelman, Andrew Adler, Harry Adriance, Jacob (Rev. Dr.) and family Ady, George Affolter, Frederick SEE ALSO: oversize Aichelman, Frank and Agnew, Spiro T. family Aicher, Cornelius and family Aiken, John W. Aitken, Leonard L. Akeroyd, Richard G. Jr. Alberghetti, Carla Albert, John David (“Uncle Johnnie”) Albi, Charles and family Albi, Rudolph (Dr.) Alda, Frances Aldrich, Asa H. Alexander, D. M. Alexander, Sam (Manitoba Sam) Alexis, Alexandrovitch (Grand Duke of Russia) Alford, Nathaniel C. Alio, Giusseppi Allam, James M. Allegretto, Michael Allen, Alonzo Allen, Austin (Dr.) Allen, B. F. (Lt.) Allen, Charles B. Allen, Charles L. Allen, David Allen, George W. Allen, George W. Jr. Allen, Gracie Allen, Henry (Guide in Middle Park-Not the Henry Allen of Early Denver) Allen, John Thomas Sr. Allen, Jules Verne Allen, Orrin (Brick) Allen, Rex Allen, Viola Allen William T. -

Jabotinsky Wrecked Zionists' Hope for 'Water for Peace' in Mideast

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 29, Number 20, May 24, 2002 Jabotinsky Wrecked Zionists’ Hope For ‘Water for Peace’ in Mideast by Steven Meyer The first of a series of articles revealing how Vladimir Ze’ev neer for the construction of the colossal Hoover Dam project Jabotinsky, the factional sympathizer of Mussolini and Hitler in the United States, and its man-made lake is named in his in the Zionist movement, was used by the British oligarchy to honor. prevent the creation of independent, industrially and scien- Mead’s initial report suggested that using his techniques, tifically developed states in the Middle East. The Likud Prime Palestine could become as verdant as Southern California, Ministers known as Jabotinsky’s “Princes” have brought the and that the Jordan Valley, like the Imperial Valley in Califor- Middle East to the brink of general religious war. nia, had the capacity “to supply distant cities with fruits and vegetables.” Mead’s projects included the building of a dam In 1976, economist and Presidential candidate Lyndon in the upper Jordan Valley that would “light cities, turn the LaRouche issued a policy statement, known as the Oasis Plan, wheels of factories, pump water for irrigation, and give to the which would establish a Middle East peace to “make the de- country a varied and prosperous industrial life.” serts bloom.” LaRouche’s policy was that a durable peace The following year, Meade became the Commissioner of could be established only through economic cooperation be- the U.S. Bureau of Land Reclamation, a position he occupied tween Israel and her Arab neighbors. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

ELWOOD MEAD: IRRIGATION ENGINEER AND SOCIAL PLANNER Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kluger, James R. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 10:58:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290253 71-8429 KLUGER, James Robert, 1939- ELWOOD MEAD: IRRIGATION ENGINEER AND SOCIAL PLANNER. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1970 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED ELWOOD MEAD: IRRIGATION ENGINEER AND SOCIAL PLANNER by James Robert Kluger r A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 7 0 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by James Robert KLuger entitled Elwood Mead: Irrigation Engineer and Social Planner be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the Doctor of Philosophy degree of ^ /, 1970 Dissertation Director Date\J After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:*" ^ Ow, S, /fro "This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. -

Thesis Accelerating Waters: an Anthropocene History

THESIS ACCELERATING WATERS: AN ANTHROPOCENE HISTORY OF COLORADO’S 1976 BIG THOMPSON FLOOD Submitted by Will Wright Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2016 Master’s committee: Advisor: Mark Fiege Jared Orsi Adrian Howkins Jill Baron Copyright by Will Wright 2016 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ACCELERATING WATERS: AN ANTHROPOCENE HISTORY OF COLORADO’S 1976 BIG THOMPSON FLOOD Scale matters. But in the Anthropocene, it is not clear how environmental scholars navigate between analytical levels from local and regional phenomena on the one hand, to global Earth-system processes on the other. The Anthropocene, in particular, challenges the ways in which history has traditionally been conceived and narrated, as this new geological epoch suggests that humans now rival the great forces of nature. The Big Thompson River Flood of 1976 provides an opportunity to explore these issues. Over the Anthropocene’s “Great Acceleration” spike, human activities and environmental change intensified both in Colorado’s Big Thompson Canyon and across much of the world. The same forces that amplified human vulnerability to the catastrophic deluge on a micro-level through highway construction, automobile vacationing, and suburban development were also at work with the planetary upsurge in roads, cars, tourism, atmospheric carbon dioxide, and flooding on the macro-level. As a theoretical tool, the Anthropocene offers a more ecological means to think and write about relationships among time and space. ii PREFACE The idea for this thesis started with several disasters and a cartoon—though not together. -

Hoover Dam: Scientific Studies, Name Controversy, Tourist Attraction, and Contributions to Engineering

Hoover Dam: Scientific Studies, Name Controversy, Tourist Attraction, and Contributions to Engineering J. David Rogers1, Ph.D., P.E., P.G., F. ASCE 1K.F. Hasslemann Chair in Geological Engineering, Missouri University of Science & Technology, Rolla, MO 65409; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Hoover Dam was a monumental accomplishment for its era which set new standards for post-construction performance evaluations. Many landmark studies were undertaken as part of the Boulder Canyon project which shaped the future of dam building. Some of these included: comprehensive surveys of reservoir sedimentation, which continue to the present; the discovery of turbidity currents operating in Lake Mead; the nature of nutrient-rich sediment contained in these density currents; cooperative studies of crustal deflection beneath the weight of Lake Mead; and reservoir-triggered seismicity. These studies were of great import in evaluating the impacts of large dams and reservoirs, world-wide, and have led to a much better understanding of reservoir siltation than previously existed. Hoover Dam was also the first dam to be fitted with strong motion accelerometers and Lake Mead the first reservoir to have an array of seismographs to evaluate the impacts of reservoir triggered seismicity. Along the way, there has been considerable confusion about the name of the dam, which was changed in 1931, 1933, and 1947. Most of the project documents are filed or referred to by the several names employed by Reclamation between 1928-1947. The article concludes with a brief description of the Boulder Canyon Project Reports, which have been translated into many different languages and distributed world-wide.