Revista Latinoamericana De Herpetologia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

Final Report for the University of Nottingham / Operation Wallacea Forest Projects, Honduras 2004

FINAL REPORT for the University of Nottingham / Operation Wallacea forest projects, Honduras 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS FINAL REPORT FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM / OPERATION WALLACEA FOREST PROJECTS, HONDURAS 2004 .....................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................................................3 List of the projects undertaken in 2004, with scientists’ names .........................................................................4 Forest structure and composition ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bat diversity and abundance ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Bird diversity, abundance and ecology ............................................................................................................................ 4 Herpetofaunal diversity, abundance and ecology............................................................................................................. 4 Invertebrate diversity, abundance and ecology ................................................................................................................ 4 Primate behaviour........................................................................................................................................................... -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. | http://redlist-ARC.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Atropoides Picadoi Agkistrodon Bilineatus

37 Beauty of the Beast SNAKES OF COSTA RICA AA DEADLYDEADLY CHARMCHARM Large and small, colorful or drab, harmless or dangerously venomous - meet some of the most fascinating ophidians of Mesoamerica 38 Spilotes pullatus Powerful, muscular, agile and fast-moving, this diurnal and highly variable species can attain a length of 2.6 meter / 8.5 feet. Relatively common in dry lowland riverine forest from Mexico to Argentina, it makes for an impressive encounter in the field, offering a most effective defensive display which includes mouth gaping, loud hissing and extreme inflating of the throat. 39 TEXTS BY POMPILIO CAMPOS BONILLA & ANDREA FERRARI PHOTOS BY ANDREA & ANTONELLA FERRARI and POMPILIO CAMPOS CHINCHILLA osta Rica is a Central American in major international treaties and Ctropical country which thanks to its conventions for the conservation of prevailing environmental conditions nature. A member of CITES, it follow can boast a rich diversity of snakes, strict rules regulating the international with a total of 11 families, 64 genera trade in endangered species - therefore and 139 ophidian species of aquatic, snakes enjoy benefits conferred by terrestrial and arboreal habits, law, ensuring their survival. However, distributed in almost all its territory, because of the myths and popular from sea level to an elevation of about beliefs about snakes, many species of 3000 meters. Only 22 of these possess great ecological importance are still a venom capable of causing harm to victims of human ignorance and are human health - these belong to the regularly killed, mainly in agricultural family Viperidae (pit vipers with heat- areas where workers are afraid of sensitive loreal pits, with haemotoxic being bitten. -

Envenomation Caused by the Bite of the Snake Bothriechis Schlegelii. Report of Two Cases in Colombia

Case Reports 2017; 3(1) https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/care/article/view/58625 ENVENOMATION CAUSED BY THE BITE OF THE SNAKE BOTHRIECHIS SCHLEGELII. REPORT OF TWO CASES IN COLOMBIA Palabras clave: Bothriechis schlegelii; Mordeduras de serpientes; Coagulación sanguínea; Colombia. Keywords: Bothriechis schlegelii; Snake bites; Blood coagulation; Colombia. Mario Galofre-Ruiz, MD, MSc Tox Centro de Información de Seguridad sobre Productos Químicos CISPROQUIM Consejo Colombiano de Seguridad Bogotá D.C. – Colombia Corresponding author [email protected] Phone number.: (057)3157261026 CASE REPORTS ABSTRACT brown and black), helps it mimic its surround- ings. It has prehensile tail, and from two to four The bite by snakes of the Bothriechis genus is small superciliar scales, in the way of “eye- common in certain areas of Colombia such as lashes”. It feeds on baby birds, lizards, frogs the Coffee-growing Region. Due to their arbo- and rodents, inhabits tropical forests and corn real habits and defensiveness, these snakes and coffee crops, at altitudes ranging from 0 usually bite farmers in their upper limbs and to 2600 m; the viper reaches the highest alti- face. In Colombia, the incidence of accidents tude in Colombia (2,3). caused by these snakes has not been accu- In the regions in which it inhabits, it is also rately estimated yet because of deficiencies in known as cabeza de candado, granadilla, ví- recording this type of cases, as well as of the bora de tierra fría, víbora de pestañas, ya- ignorance on this reptile by health personnel ruma, veinticuatro, guacamaya, víbora rayo, working in its area of influence. -

Snakes, Centipedes, Snakepedes, and Centiserpents: Conflation of Liminal Species in Maya Iconography and Ethnozoology

f No. 9, 2004 WAYEB NOTES ISSN 1379-8286 SNAKES, CENTIPEDES, SNAKEPEDES, AND CENTISERPENTS: CONFLATION OF LIMINAL SPECIES IN MAYA ICONOGRAPHY AND ETHNOZOOLOGY. (Workshop Closing Paper Presented at the XXIVth Linda Schele Forum on Maya Hieroglyphic Writing at the University of Texas at Austin, March 2000) Harri Kettunen1 and Bon V. Davis II2 1 University of Helsinki 2 University of Texas at Austin Abstract Since the identification of centipedes in the Maya hieroglyphic corpus and iconography in 1994 by Nikolai Grube and Werner Nahm (Grube & Nahm 1994: 702), epigraphers and iconographers alike have debated whether the serpentine creatures in Maya iconography depict imaginative snakes or centipedes. In this paper we argue that most serpentine creatures with unrealistically depicted heads are neither snakes nor centipedes, but a conflation of both, and even have characteristics of other animals, such as sharks and crocodiles. Thus these creatures should more aptly be designated as zoomorphs, monsters, centiserpents, or dragons. In the present article the topic will be examined using iconographic, epigraphic, zoological, and ethozoological data. Acknowledgements We would like to express our thanks to Justin Kerr for directing the Workshop on Maya ceramics at the XXIVth Maya Meeting in Austin. We would also like to thank Justin for making available hundreds of roll-out photographs of Maya ceramics and for offering us his insights on Maya iconography. Furthermore, we would like to thank Nancy Elder, the head librarian of the Biological Sciences Library at the University of Texas at Austin for providing us numerous articles relating to our topic and for directing us to relevant sources during our research on centipedes. -

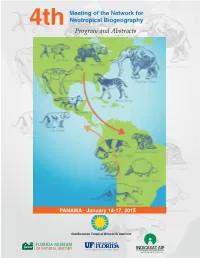

Program and Abstracts

Meeting of the Network for Neotropical Biogeography 4th Program and Abstracts PANAMA - January 14-17, 2015 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Program 4th Meeting of the Network for Neotropical Biogeography NNB4 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute 14-17 January, 2015 This meeting is being hosted by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), and financially supported by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Indicasat and the Florida Museum of Natural History/University of Florida. Organizers Liliana Londoño and Carlos Jaramillo, STRI PANAMA CHANGED THE WORLD! The Isthmus of Panama emerged from the sea millions of years ago, joining two continents and producing one of the largest vicariance events in Earth’s history: the Great American Biotic Interchange (GABI). At that time, marine populations were separated while terrestrial plants and animals underwent massive migrations between North and South America, dramatically changing the Earth. The rise of the isthmus also impacted atmospheric and oceanic circulation, including substantial changes in Atlantic and Caribbean salinity. There is no better place to have a symposium on Neotropical Biogeography! 1 NETWORK FOR NEOTROPICAL BIOGEOGRAPHY Tropical America – the Neotropics – is the most species-rich region on Earth. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the historical assembly and evolution of this extreme biodiversity constitutes a major challenge in biology, and will require hitherto unrealized inter- disciplinary scientific collaboration. The primary goals of this network are to: • Promote scientific interaction • Stimulate the exchange of material, students and researchers • Increase inter-disciplinarity between different fields • Discuss and plan joint projects and grant applications • Stimulate collaborative field work and reciprocal help with field collection of research material • Inform on upcoming events, recent papers and other relevant material The NNB was created in 2011 and has been increasing every year, with previous meetings in Germany, USA and Colombia. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: CROTALIDAE Cerrophidion Tzotzilorum

880.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: CROTALIDAE Cerrophidion tzotzilorum Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Jadin, R.C. 2010. Cerrophidion tzotzilorum. Cerrophidion tzotzilorum (Campbell) Tzotzil Montane Pitviper Nauyaca del frío, víbora Bothrops nummifer mexicanus: McCoy and Van Horn 1962:186 (part). Cerrophidion godmani: Auth, Smith, Brown, and Lintz 2000:73 (part). _ FIGURE 2. Photograph of the hemipenis of the holotype Bothrops tzotzilorum Campbell 1985:48. Type locali- _ ty, “10.9 km ESE San Cristóbal de Las Casas, of Cerrophidion tzotzilorum (UTA R 9641); (A) sulcate view, Chiapas, Mexico, elevation 2320 m.” Holotype, (B) asulcate view. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Research Cen- ter, University of Texas at Arlington (UTA) R_9641, • DIAGNOSIS. This species is parapatric with C. an adult male collected by J.A. Campbell on 8 godmani with few reports of sympatry (Campbell June 1979. 1985). It differs from C. godmani in having shorter Porthidium tzotzilorum: Campbell and Lamar 1989: and more numerous dorsal and lateral body blotches, 264. generally lower ventral scale counts, and fewer den- Cerrophidion tzotzilorum: Campbell and Lamar 1992: tary and pterygoid teeth. 24. • DESCRIPTIONS. The most complete descrip- • CONTENT. No subspecies are recognized. tions of the external morphology are in Campbell (1985, 1988), Campbell and Lamar (1989, 2004), and • DEFINITION. Cerrophidion tzotzilorum may be the Jadin (in press). smallest species of pitviper in the New World (Camp- bell and Lamar 2004); adults probably do not exceed • ILLUSTRATIONS. In the original description, 50 cm in total length. Coloration may be a dark gray- Campbell (1985) provided sketches of both the left ish brown or rust. A darker gray or brown zig_zag pat- side and dorsal views of the head of the holotype, tern extends from the neck down the entire length of along with a sulcate view of the left hemipene. -

Porthidium Lansbergii Rozei) Snake´S Venom Causing Human Accidents in Eastern Venezuela Investigación Clínica, Vol

Investigación Clínica ISSN: 0535-5133 Universidad del Zulia Girón, María E.; Ramos, María I.; Cedeño, Luisneidys; Carrasquel, Axl; Sánchez, Elda E.; Navarrete, Luis F.; Rodríguez-Acosta, Alexis Exploring the biochemical, haemostatic and toxinological aspects of mapanare dry-tail (Porthidium lansbergii rozei) snake´s venom causing human accidents in Eastern Venezuela Investigación Clínica, vol. 59, no. 3, 2018, July-September, pp. 260-277 Universidad del Zulia DOI: https://doi.org/10.22209/IC.v59n3a06 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=372960219007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Invest Clin 59(3): 260 - 277, 2018 https://doi.org/10.22209/IC.v59n3a06 Exploring the biochemical, haemostatic and toxinological aspects of mapanare dry-tail (Porthidium lansbergii rozei) snake´s venom causing human accidents in Eastern Venezuela María E. Girón1, María I. Ramos1, Luisneidys Cedeño1, Axl Carrasquel1, Elda E. Sánchez2, Luis F. Navarrete1 and Alexis Rodríguez-Acosta1 1Laboratorio de Inmunoquímica y Ultraestructura, Instituto Anatómico “José Izquierdo”, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela. 2National Natural Toxins Research Center (NTRC), Texas A&M University-Kingsville, MSC 158, Kingsville, TX, USA. Key words: Porthidium lansbergii rozei; fibrinolysis; haemorrhages; lethality; venom. Abstract. Porthidium lansbergii rozei (P.l.rozei) is a snake species belonging to the Venezuelan ophidian-fauna causing relatively frequent human accidents. This study has been developed to enrich the medical information about this snake´s accident, which is often handled with difficulties due to the ignorance about its toxic activities. -

A New Species of Hognose Pitviper, Genus Porthidium, from the Southwestern Pacific of Costa Rica (Serpentes: Viperidae)

Rev. Biol. Trop. 51(3): 797-804, 2003 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu A new species of hognose pitviper, genus Porthidium, from the southwestern Pacific of Costa Rica (Serpentes: Viperidae) William W. Lamar1 & Mahmood Sasa2 1 College of Sciences, University of Texas, 3900 University Blvd., Tyler, Texas 75799, USA. 2 Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Universidad de Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica, and Organization for Tropical Studies, San José, Costa Rica. Received 12-IV-2003. Corrected 29-VIII-2003. Accepted 01-IX-2003. Abstract: A new species of terrestrial pitviper, Porthidium porrasi, is described from mesophytic forests of the Península de Osa and surrounding area of the Pacific versant of southwestern Costa Rica. It is most similar to P. nasutum and is characterized by a pattern of bands, persistence of the juvenile tail color in adults, and a high number of dorsal scales. Analysis of mtDNA sequences confirms its distinction from P. nasutum. The existence of this species reinforces the notion of elevated herpetofaunal endemism in southwestern Costa Rica. Key words: Porthidium porrasi, Porthidium nasutum, Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica, Central America. The pitviper genus Porthidium has under- genus Atropoides (Werman 1992); the mon- gone several revisions since its conception by tane pitvipers, genus Cerrophidion (Campbell Cope (1871). The genus has included two to and Lamar 1992); and the hognosed pitvipers, 17 species of terrestrial snakes, most of them genus Porthidium (Campbell and Lamar 1989, less than a meter in total length, and most with in press). Despite the considerable morpho- middle American distributions (Amaral 1927, logical differences, the three genera form a 1929, 1944, Boulenger 1896, Campbell and monophyletic clade that originated and Lamar 1989, Cope 1871, Dunn 1928). -

Porthidium Dunni (Hartweg and Oliver, 1938)

Porthidium dunni (Hartweg and Oliver, 1938). Dunn’s Hognosed Pitviper is a “priority two species” that has been assessed Environmental Vulnerability Score of 16 (see the following article). This pitviper is found primarily at low elevations along the foothills of the Sierra Madre del Sur physiographic region and the coastal plain of the Planicie Costera del Pacífico and Planicie Costera de Tehuantepec physiographic regions (Mata-Silva et al., 2015b) in southern Oaxaca and extreme western Chiapas, Mexico. This individual was found ca. 3.6 km NNW of La Soledad, Municipio de Villa de Tututepec de Melchor Ocampo, Oaxaca. ' © Vicente Mata-Silva 543 www.mesoamericanherpetology.com www.eaglemountainpublishing.com The endemic herpetofauna of Mexico: organisms of global significance in severe peril JERRY D. JOHNSON1, LARRY DAVID WILSON2, VICENTE MATA-SILVA1, ELÍ GARCÍA-PADILLA3, AND DOMINIC L. DESANTIS1 1Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79968-0500, United States. E-mail: [email protected], and [email protected], and [email protected] 2Centro Zamorano de Biodiversidad, Escuela Agrícola Panamericana Zamorano, Departamento de Francisco Morazán, Honduras. E-mail: [email protected] 3Oaxaca de Juárez, Oaxaca 68023, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Life on Earth exists due to the interactions among the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and litho- sphere. Humans, however, have created and are faced with the consequences of an interrelated set of problems that impact all of these spheres, including the biosphere. The decline in the diversity of life is a problem of global dimensions resulting from a sixth mass extinction episode created by humans.