New World, New Rules? 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Global Go to Think Tank Index Report

LEADING RESEARCH ON THE GLOBAL ECONOMY The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening prosperity and human welfare in the global economy through expert analysis and practical policy solutions. Led since 2013 by President Adam S. Posen, the Institute anticipates emerging issues and provides rigorous, evidence-based policy recommendations with a team of the world’s leading applied economic researchers. It creates freely available content in a variety of accessible formats to inform and shape public debate, reaching an audience that includes government officials and legislators, business and NGO leaders, international and research organizations, universities, and the media. The Institute was established in 1981 as the Institute for International Economics, with Peter G. Peterson as its founding chairman, and has since risen to become an unequalled, trusted resource on the global economy and convener of leaders from around the world. At its 25th anniversary in 2006, the Institute was renamed the Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics. The Institute today pursues a broad and distinctive agenda, as it seeks to address growing threats to living standards, rules-based commerce, and peaceful economic integration. COMMITMENT TO TRANSPARENCY The Peterson Institute’s annual budget of $13 million is funded by donations and grants from corporations, individuals, private foundations, and public institutions, as well as income on the Institute’s endowment. Over 90% of its income is unrestricted in topic, allowing independent objective research. The Institute discloses annually all sources of funding, and donors do not influence the conclusions of or policy implications drawn from Institute research. -

Personal Use Cannabis Rules Special Adopted New Rules: N.J.A.C

NEW JERSEY CANNABIS REGULATORY COMMISSION Personal Use Cannabis Rules Special Adopted New Rules: N.J.A.C. 17:30 Adopted: August 19, 2021 by New Jersey Cannabis Regulatory Commission, Dianna Houenou, Chair. Filed: August 19, 2021 Authority: N.J.S.A. 24:6I-31 et seq. Effective Date: August 19, 2021 Expiration Date: August 19, 2022 This rule may be viewed or downloaded from the Commission’s website at nj.gov/cannabis. These rules are adopted pursuant to N.J.S.A. 24:6I-34(d)1a of the New Jersey Cannabis Regulatory, Enforcement Assistance, and Marketplace Modernization Act, N.J.S.A. 24:6I- 31 et seq., and became effective upon acceptance for filing by the Office of Administrative Law. The specially adopted new rules shall be effective for a period not to exceed one year from the date of filing of the new rules, that is, until August 19, 2022. The Commission has provided this special adoption to the Attorney General, State Treasurer, Commissioner of Health, and Commissioner of Banking and Insurance for a consultation period, after which the Commission anticipates filing a proposal to readopt these rules with amendments reflecting the results of that consultation. In accordance with N.J.S.A. 24:6I-34(d)1b the rules, as readopted, will become effective upon acceptance for filing by the Office of Administrative Law if filed on or before the expiration date of the rules published herein. The adopted amendments will be effective upon publication in the New Jersey Register. Federal Standards Analysis The Cannabis Regulatory, Enforcement Assistance, and Marketplace Modernization Act obliges the Cannabis Regulatory Commission to promulgate rules necessary or proper to enable it to carry out the Commission’s duties, functions, and powers with respect to overseeing the development, regulation, and enforcement of activities associated with the personal use of cannabis pursuant to P.L.2021, c.16. -

Kiiara Drops New Track & Music Video “Open My Mouth

KIIARA DROPS NEW TRACK & MUSIC VIDEO “OPEN MY MOUTH” – OUT NOW FEATURING DESIGNER CHRISTIAN COWAN AND HIS FALL FW19 RUNWAY LOOKS DEBUT ALBUM SET FOR RELEASE FALL 2019 “OPEN MY MOUTH” SINGLE ART HERE (PHOTO CREDIT: TRENT BARBOZA) NEW YORK, NY (June 7, 2019) – Today, 24-year-old multiplatinum singer-songwriter and “Princess of Chop-Pop” KIIARA debuts a brand new song, “Open My Mouth,” which marks the lead single from her highly anticipated debut album set for release this fall via Atlantic Records. The track, and its accompanying video, gives fans a taste of what’s to come off the forthcoming record – listen HERE. “Open My Mouth,” co-written by Kiiara, Amy Allen (Halsey’s “Without Me”, Selena Gomez’s “Back To You”), Scott Harris (Shawn Mendes’ “Treat You Better” and “There’s Nothin’ Holding Me Back”), Ian Kirkpatrick (Dua Lipa’s “New Rules”, Julia Michaels’ EP), and Joe London (Pitbull, Jason Derulo, Fifth Harmony) showcases Kiiara’s unique ability to blur the lines between genres with her signature vocals and honest lyrics. “Art is open for interpretation, so while some will listen to this song and relate to it based on relationships they’ve had in their lives, for me this song is about the relationship I have with myself,” Kiiara says of the new track. “I’ve struggled with mental health issues for my entire life. I’ve felt silenced, I’ve felt alone, and I’ve felt afraid. To me, this song is about facing these realities and putting it all out there. It feels empowering to open up and finally speak my truth, and I hope in doing so I can encourage others to let their guard down and do the same, so they don’t feel so alone and helpless.” The accompanying music video, directed by Juliana Carpino, features designer Christian Cowan and fashion from his FW19 line along with a special cameo appearance from Austin Mahone – watch HERE. -

In the Style of Dua Lipa Teacher Guide

Remix Project Teacher Guide INCLUDED IN THE RESOURCE: • Re-created full Garageband session of Dua Lipa’s Number 1 track ‘New Rules’ • Mp3 file of the re-created session • Empty Garageband session containing relevant tracks, structure & instruments • Re-created samples & MIDI parts to create a unique remix containing: o 48 Drum samples (Cymbals, FX, Kicks, Percussion, Snares & claps) o 36 Samples containing New Rules instrumental stems, hooks and cuts o 7 Vocal samples, riffs and hooks from 6 other Dua Lipa tracks for remixing/mash-up projects o MIDI parts for bass, keys and pads o Full acapella samples from New Rules that students can edit and re-use • Teacher Guide • Classroom Powerpoint with success criteria and teaching support content FIND MORE IN THE STYLE OF… We’re continuing to expand our ‘In The Style Of…’ resources to include a wide range of artists and genres. Please check the resources section of our website for regular updates! 5 Approaches to using this resource: 1. Developing understanding of popular music through exploring structure, lyrics and instrumentation 2. Developing music technology skills and exploring how technology and effects are used to create popular music 3. Create a Remix or mashup 4. Performance activity using the session as a backing track & guide 5. Exploring lyric writing through re-writing and re-recording lyrics to a popular song Setting out a Scheme of Learning “I loved the Deciding which approach you want to use with this resource is project and the crucial to establishing your success criteria or learning objectives at the start of the unit. -

DUA LIPA We're Good and Future Nostalgia the MOONLIGHT EDITION

DUA LIPA RELEASES NEW SINGLE 'WE’RE GOOD’ TAKEN FROM ‘FUTURE NOSTALGIA - THE MOONLIGHT EDITION’ BOTH OUT TODAY Today, Dua Lipa releases her new single ‘We’re Good’; dropping the tempo the track is a sensual tale of two lovers needing to go their separate ways. Produced by Sly this slow groove track is taken from ‘Future Nostalgia - The Moonlight Edition, which also includes the hit singles ‘Don’t Start Now’, ‘Physical’, ‘Break My Heart’ and ‘Levitating’ The video for ‘We're Good’ sees Dua Lipa serenading the guests in an exquisite looking restaurant on a ship from the turn of the 20th Century. In the same restaurant a lobster’s fate takes a very unexpected turn too….. The beautiful and surreal video is directed by Vania Hetmann & Gal Muggla. ‘Future Nostalgia - The Moonlight Edition’ is also released today on all digital platforms. This deluxe edition features three more previously unheard tracks ‘If It Ain’t Me’, ‘That Kind of Women’ and ‘Not My Problem (feat. JID)’ and will include the top 10 smash hit single from Miley Cyrus Feat Dua Lipa ‘Prisoner’ which has reached 250m streams worldwide. Also on the album is ‘Fever’ with Angèle, which spent three weeks at #1 in France and 11 weeks at #1 in Belgium and J Balvin, & Bad Bunny ‘UN DIA (ONE DAY) (Feat. Tainy) which has hit over 500m streams. Full track listing Future Nostalgia - The Moonlight Edition 1. Future Nostalgia 2. Don’t Start Now 3. Cool 4. Physical 5. Levitating 6. Pretty Please 7. Hallucinate 8. Love Again 9. -

Song List 3/2021 1 | Page

Song List 3/2021 1 | Page Contemporary: Artist Rollin in the Deep Adele Someone Adele To Make You Feel My Love Adele I Found You Alabama Shakes Mr. Saxobeat Alexandra Stan Girl on fire Alicia Keys If I ain't got you Alicia Keys No One Alicia Keys Follow me Aly Us Best Day of My Life American Authors Break Free Ariana Grande Sweet but psycho Ava Max Wake Me Up Avicii Poison BBD Love On Top Beyoncé Crazy in Love Beyoncé Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) Beyoncé I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow Black Eyed Peas Let’s Get it Started Black Eyed Peas No Diggity Blackstreet Finessee Bruno Mars ft. Cardi B. Just the Way You Are Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars Marry you Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Let's Go Calvin Harris Sweet Nothing Calvin Harris/Florence Welsh I like it Cardi B Up Cardi B Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Forget You Cee Lo Green Don’t Wake Me Up Chris Brown Yeah 3X Chris Brown International Love Chris Brown Forever Chris Brown Song List 3/2021 2 | Page Turn Up the Music Chris Brown Ain’t No Other Man Christina Aguilera Girls just wana have fun Cyndi Lauper Time After Time Cyndi Lauper Viva La Vida Cold Play Put Your Records On Corinne Bailey Rae Get Lucky Daft Punk Cake by the ocena DNCE Bad Girl Donna Summer Last Dance Donna Summer Perfect Duet Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran I Like It Enrique Iglesias Good Feelin’ Flo Rida Club Can't Handle Me Flo Rida Crazy Gnarles Barkley Without me Halsey I Love It Icona Pop Let It Go Idina Menzel Fancy Iggy Azalea Talk Dirty Jason Derulo -

The New Rules of Engagement Cmos Rethink Their Marketing Mix

The New Rules of Engagement CMOs Rethink Their Marketing Mix IN ASSociAtioN WitH: © Copyright Forbes 2010 1 KEY FINDINGS To gain a deeper understanding of how marketers are defining and acting on customer engagement, Forbes Insights, in association with experience marketing agency George P. Johnson, surveyed more than 300 marketing leaders of large companies. Key findings of the study include: • As traditional “interrupt and repeat” advertising models are fading as brand-defining tools in favor of customer “conversations” and advocacy, engagement is becoming the way marketers are creating brand experiences worth discussing. • CMOs are building their customer-facing programs with engagement in mind, and making it a KPI in their dialog with top corporate management. • Coming up with a definition of customer engagement appropriate to their organization and brand—and the accompanying metrics to measure it—is a core responsibility of the CMO. • In assessing engagement, experiential and digital opt-in methods are frequently rated as the methods that engage with customers most deeply. Yet CMOs aren’t necessarily aligning their marketing budgets to these priorities. • Companies may be getting in their own way when it comes to drafting their engagement strategies. Among the top inhibitors: lack of a well defined approach to engagement, and poorly articulated benefits for loyal customers. • Despite an understanding of the importance of engagement, more than a quarter of companies don’t have a specific engagement strategy in place. More than a third believe their companies are doing only a fair or poor job engaging their audiences. • For most marketing executives, effective engagement translates into greater sales, higher margins, and repeat purchase behavior. -

Ariana Henare Better Band | Artist Song List

ARIANA HENARE BETTER BAND | ARTIST SONG LIST Seaside - The Kooks Big Jet Plane - Angus and Julia Stone Chateau Marmot - Angus and Julia Stone Yellow Brick Road - Angus and Julia Stone Dreams - Fleetwood Mac Go your own way - Fleetwood Mac Rhiannon - Fleetwood Mac Landslide - Fleetwood Mac Happy - Pharrell Williams I can change - Lake Street Drive Toxic - Britney Spears The one that I want - Grease cover Cherry Wine - Hozier Take me to church - Hozier Work Song - Hozier Someone New - Hozier Knocking on heavens door - Bob Dylan Watermelon Sugar - Harry Styles Adore You - Harry Styles Scared to be lonely - Dua Lipa New Rules - Dua Lipa Levitating - Dua Lipa Crazy - Gnarls Barkley Naive - The Kooks Yellow Mellow - Ocean Alley Get away - Katchafire In the air - L.A.B. Ain’t nobody - Chaka Khan Lighthouse - The Waifs Say you won’t let go - James Arthur Feels like this - Maisie Peters Better When We’re Together - Jack Johnson Special - Six60 Green Bottles - Six60 Forever - Six60 Catching feelings - Six60 Feel the l love - John Newman (Six60 cover) Hallelujah - Jeff Buckley BETTER BAND | 021 1795953 | [email protected] Stand By Me - Ben E. King (cover) Can’t take my eyes off of you - Frakie Valli Pack up - Eliza Doolittle / Don’t worry be happy - Bobby McFerrin (Mash up) Riptide - Vance Joy Sunday Morning - Maroon 5 Sugar - Maroon 5 Billie Jean - MJ September Song - J P Cooper Get Lucky - Daft Punk ft. Pharrell Williams Yours to bear - Honey, Honey Sexual Healing - Lonely Boy - The Black Keys How would you feel - Ed Sheehan Gold rush - Ed -

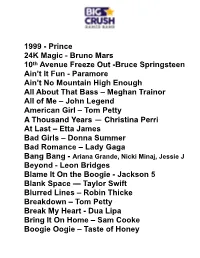

BC Song List 2020 Copy

1999 - Prince 24K Magic - Bruno Mars 10th Avenue Freeze Out -Bruce Springsteen Ain’t It Fun - Paramore Ain’t No Mountain High Enough All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor All of Me – John Legend American Girl – Tom Petty A Thousand Years — Christina Perri At Last – Etta James Bad Girls – Donna Summer Bad Romance – Lady Gaga Bang Bang - Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj, Jessie J Beyond - Leon Bridges Blame It On the Boogie - Jackson 5 Blank Space — Taylor Swift Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke Breakdown – Tom Petty Break My Heart - Dua Lipa Bring It On Home – Sam Cooke Boogie Oogie – Taste of Honey Brick House - Commodores Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle Cake By the Ocean - DNCE California Girls – Katy Perry California Love - 2Pac Call Me Al – Paul Simon Can’t Get Enough of Your Love-Barry White Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can’t Stop the Feeling - Justin Timberlake Can’t Take My Eyes Off You - Frankie Valli Car Wash – Rose Royce Celebration – Kool & the Gang Chain of Fools – Aretha Franklin Chained to the Rhythm — Katy Perry Cinema – Benny Benassi (acoustic) Cold Sweat - James Brown Come Away With Me – Norah Jones Coming Home - Leon Bridges Crazy In Love - Beyonce Crazy Love – Van Morrison Dancing Queen - ABBA Days Like This – Van Morrison Domino - Van Morrison Domino - Jessie J Don’t Start Now - Dua Lipa Don’t Know Why – Nora Jones Don’t Stop Believin’ - Journey Everybody (Backstreet’s Back) - Backstreet Boys Everything – Michael Buble’ Everywhere — Fleetwood Mac Feel This Moment – Pitbull ft Christina A -

The Connection Song List

THE CONNECTION SONG LIST Thank you for downloading our song list! Which specific songs we perform at any given event is based on 3 factors: 1) Popular music that will create an unforgettable party. We “read” your crowd and all the age groups in attendance, calling songs accordingly. 2) General musical styles that fit into your personal preferences. 3) What we perform best; songs that help to make us who we are. We don’t work with pre-determined set lists, but we will try to include many of your preferences & favorites. This in addition to you choosing all the material for any formal dances. We’ll also learn two new songs for you that are not a regular part of our repertoire! (formal dances take precedence). Top 40 Song Title Artist Silk Sonic Leave The Door Open The Weeknd Blinding Lights Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande Rain On Me Kygo & Whitney Houston Higher Love Harry Styles Watermelon Sugar Dua Lipa Don't Start Now Lizzo Juice Lizzo Truth Hurts Lil NasX ft. Billy Ray Cyrus Old Town Road Jonas Brothers Sucker The Blackout Allstars / Cardi B I Like It Like That Lady Gaga & Bradley Cooper Shallow Zedd, Maren Morris, Grey The Middle Luis Fonsi Despacito Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars That's What I Like Bruno Mars Ft. Cardi B Finesse Camila Cabello Havana Dua Lipa, Calvin Harris One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Ed Sheeran Shape Of You Shawn Mendes There's Nothing Holding Me Back Clean Bandit Rockabye Niall Horan Slow Hands Sia Cheap Thrills Ariana Grande Thank U, Next Drake One Dance The Chainsmokers Closer -

Navigating the New Media Landscape

IPI ReportProduced in Partnership with Uhe Poynter Institute Brave News Worlds Navigating the New Media Landscape Preface or the past three years, discussions about the future of the news media have centered Fon the decline of the so-called golden age of journalism and the descent into a chaos characterised by splintered audiences, decimated balance sheets, and the muscling-in of amateurs. Fearing that their halcyon days as the guardians of information are num- bered, many editors and journalists have engaged in collective navel-gazing, asking themselves: What went wrong? But is the future really so bleak? Is the decline a global phenomenon? Are we moving into a new ‘golden age’? And what does it mean for press freedom? To find answers to these pressing questions, the International Press Institute teamed up with the Poynter Institute, one of the premier journalism training centers in the world, to set out on a global investigation assembling an international group of editors, jour- nalists, visionaries and sceptics to discover how the future of the news is developing around the world. The result is that after a 10-year absence, the IPI Report series has returned, revamped and reinvigorated with a new edition entitled “Brave News Worlds”, a report that charts the exciting times ahead for the news media and uncovers the many different global perspectives thereof. Picking up where the IPI Report series left off in 2000, “Brave News Worlds” explores what the next 10 years hold for the news and journalism industry and offers insight into how journalists and non-journalists alike can take advantage of changes in the media and technology to make the future of news a bright one. -

A D E L E R E V E L L A

THE NEW RULES SERIES FOREWORD BY DAVID MEERMAN SCOTT A D E L E R E V E L L A How to GAIN INSIGHT into YOUR CUSTOMER’S EXPECTATIONS, ALIGN YOUR MARKETING STRATEGIES, and WIN MORE BUSINESS 3GFFIRS 02/07/2015 2:44:38 Page v This book is dedicated to every marketer who questions the wisdom of making stuff up. 3GFTOC 02/07/2015 14:12:16 Page vii Contents Foreword David Meerman Scott xiii Acknowledgments xvii Introduction: Listen First, Then Speak xix Why Is Everyone Talking about Buyer Personas? xx Will This Approach Work for You? xxii PART I Understanding the Art and Science of Buyer Personas 1 Chapter 1 Understand Buying Decisions and the People Who Make Them 3 Why the “Know Your Customer” Rule Has Been Redefined 5 A Clothes Dryer’s Extra Setting Made All the Difference 6 Will You Understand Your Buyers’ Decisions? 7 Relying on Buyer Demographics and Psychographics 10 How Marketers Benefit from Buyer Profiles 11 Buying Insights Complete Your Persona 12 High-Consideration Decisions Reveal the Best Insights 13 Buying Insights from a Quick Trip to London 15 vii 3GFTOC 02/07/2015 14:12:16 Page viii viii Contents Chapter 2 Focus on the Insights That Guide Marketing Decisions 19 Listening to Kathy 20 Frustrated, A Newly Minted Consultant Invents Personas 22 Buyers Have Distinct Expectations 23 The 5 Rings of Buying Insight 25 Give Your Buyer a Seat at the Table 27 Buying Insight Opens Doors to C-Level Executives 31 Chapter 3 Decide How You Will Discover Buyer Persona Insights 35 The Most Important Nine Months of My Career 36 How Interviews Reveal