PETERS-THESIS-2016.Pdf (4.082Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Vol 28 No 2 AIM Newsletter

The United States Secretariat of the Alliance for International Monasticism www.aim-usa.org Volume 28 No. 2 2019 [email protected] Mother Mary, You Birthed Jesus Help Us Rebirth Our World Meet a Monastery in Asia Monastere Des Benedictines, Notre-Dame De Koubri, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso Effects of Climate Change by Sr. Marie de l’Eucharistie Intro: In the beauty of creation, the Lord reveals His plants, thus maintaining the greenery of the environment in goodness and love. Unfortunately, certain climatic changes and around the monastery. negatively impact our area, a village named Koubri, not far By our silent presence in our nation, Burkina Faso, our from Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, where is situated our monastic community is part of the prophetic voices in the Benedictine monastic community, Monastère Notre Dame Church calling to hope through constant prayer and confidence de Koubri. in the Lord’s divine providence. We reach out to the poor and We observe with concern the generally reduced rainfall, hungry by offering hospitality to all who knock on our doors which is a necessity for our crop growing season, accompanied as we would receive Christ Himself. by generally increased temperatures due to global warming. We are united with all Christians whose hearts ache for unity The prolonged drought and heat decrease our water supply and reconciliation with ourselves and with nature, which visibly and impede crop growth. This has generally decreased food represents God’s presence amidst us. We sincerely hope for supply in the farming communities. There is increased peace in every heart and in every home. -

Abbot Suger's Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis

DE CONSECRATIONIBUS: ABBOT SUGER’S CONSECRATIONS OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. DENIS by Elizabeth R. Drennon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth R. Drennon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Elizabeth R. Drennon Thesis Title: De Consecrationibus: Abbot Suger’s Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis Date of Final Oral Examination: 15 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Elizabeth R. Drennon, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Erik J. Hadley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Lisa McClain, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION I dedicate this to my family, who believed I could do this and who tolerated my child-like enthusiasm, strange mumblings in Latin, and sudden outbursts of enlightenment throughout this process. Your faith in me and your support, both financially and emotionally, made this possible. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lisa McClain for her support, patience, editing advice, and guidance throughout this process. I simply could not have found a better mentor. -

National Regional State Aid Map: France (2007/C 94/13)

C 94/34EN Official Journal of the European Union 28.4.2007 Guidelines on national regional aid for 2007-2013 — National regional State aid map: France (Text with EEA relevance) (2007/C 94/13) N 343/06 — FRANCE National regional aid map 1.1.2007-31.12.2013 (Approved by the Commission on 7.3.2007) Names of the NUTS-II/NUTS-III regions Ceiling for regional investment aid (1) NUTS II-III Names of the eligible municipalities (P: eligible cantons) (Applicable to large enterprises) 1.1.2007-31.12.2013 1. NUTS-II regions eligible for aid under Article 87(3)(a) of the EC Treaty for the whole period 2007-2013 FR93 Guyane 60 % FR91 Guadeloupe 50 % FR92 Martinique 50 % FR94 Réunion 50 % 2. NUTS-II regions eligible for aid under Article 87(3)(c) of the EC Treaty for the whole period 2007-2013 FR83 Corse 15 % 3. Regions eligible for aid under Article 87(3)(c) of the EC Treaty for the whole period 2007-2013 at a maximum aid intensity of 15% FR10 Île-de-France FR102 Seine-et-Marne 77016 Bagneaux-sur-Loing; 77032 Beton-Bazoches; 77051 Bray-sur-Seine; 77061 Cannes-Ecluse; 77073 Chalautre-la-Petite; 77076 Chalmaison; 77079 Champagne-sur-Seine; 77137 Courtacon; 77156 Darvault; 77159 Donnemarie-Dontilly; 77166 Ecuelles; 77167 Egligny; 77170 Episy; 77172 Esmans; 77174 Everly; 77182 La Ferté-Gaucher; 77194 Forges; 77202 La Genevraye; 77210 La Grande-Paroisse; 77212 Gravon; 77236 Jaulnes; 77262 Louan- Villegruis-Fontaine; 77263 Luisetaines; 77275 Les Marêts; 77279 Marolles-sur-Seine; 77302 Montcourt-Fromonville; 77305 Montereau-Fault-Yonne; 77325 Mouy-sur-Seine; 77333 Nemours; 77379 Provins; 77396 Rupéreux; 77403 Saint-Brice; 77409 Saint-Germain-Laval; 77421 Saint-Mars-Vieux- Maisons; 77431 Saint-Pierre-lès-Nemours; 77434 Saint-Sauveur-lès-Bray; 77452 Sigy; 77456 Soisy-Bouy; 77467 La Tombe; 77482 Varennes-sur-Seine; 77494 Vernou-la-Celle-sur-Seine; 77519 Villiers-Saint-Georges; 77530 Voulton. -

Pope Francis Visit to Geneva, Update the French Catholic Magazine La

Pope Francis Visit to Geneva, update The French Catholic magazine La Croix International published an interview of a World Council of Churches (WCC) leader on May 31, to update their readers on Pope Francis' June 21 visit. Pastor Martin Robra, co-secretary of the mixed working group between the World Council of Churches and the Catholic Church, "credits Pope Francis with ushering in a new springtime for ecumenism." This working group, set up in 1965, is the answer to the continually discussed challenge of the Catholic Church formally joining the WCC. One of the main problems of Catholic membership is the size of the Catholic Church. It outnumbers all the other 348 members of the World Council of Churches. This is one of the several reasons the Catholic Church has not formally joined. However, there is membership by Catholics on the Faith and Order Commission, and the Mission and Evangelism Commission. The Catholic Church is considered an "Observer" in the entire structure of the WCC. Robra also contrasted the upcoming visit of Pope Francis, with previous visits to the WCC headquarters in Geneva by Popes Paul VI and John Paul II. When they visited Geneva, they did not concentrate so much on going to the WCC headquarters. And he said "Pope Francis comes first of all as head of the Catholic Church. ..We hope that together we can continue a pilgrimage of justice and peace to those at the margins of societies, those yearning for justice and peace in this violence-stricken world and its unjust political and economic relationships." A summary of the entire interview can be found on the La Croix International website, English version. -

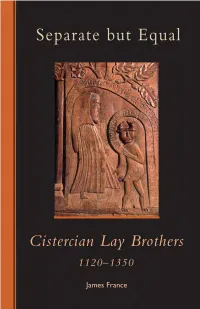

Separate but Equal: Cistercian Lay Brothers 1120-1350

All content available from the Liturgical Press website is protected by copyright and is owned or controlled by Liturgical Press. You may print or download to a local hard disk the e-book content for your personal and non-commercial use only equal to the number of copies purchased. Each reproduction must include the title and full copyright notice as it appears in the content. UNAUTHORIZED COPYING, REPRODUCTION, REPUBLISHING, UPLOADING, DOWNLOADING, DISTRIBUTION, POSTING, TRANS- MITTING OR DUPLICATING ANY OF THE MATERIAL IS PROHIB- ITED. ISBN: 978-0-87907-747-1 CISTERCIAN STUDIES SERIES: NUMBER TWO HUNDRED FORTY-SIX Separate but Equal Cistercian Lay Brothers 1120–1350 by James France Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices Abbey of Gethsemani 3642 Monks Road Trappist, Kentucky 40051 www.cistercianpublications.org © 2012 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, mi- crofiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data France, James. Separate but equal : Cistercian lay brothers, 1120-1350 / by James France. p cm. — (Cistercian studies series ; no. 246) Includes bibliographical references (p. -

Ascent to the Summit Lent 2020 with Saint John of the Cross

Introduction Ascent to the summit Lent 2020 with Saint John of the Cross tely, violent opposition arose and was un- 1. The life of Saint John leashed against Saint Teresa and her work. of the Cross (1542-1591) In this difficult context, John was kidnapped and held for nine months in the Carmelite Juan de Yepes was born in 1542 in convent in Toledo in terrible conditions. Yet Castille in a family of poor weavers. After this moment of abandonment is for him the death of Juan’s father, the family moved the crucible of a mystical experience that to Medina del Campo to get out of poverty. becomes a resource: while he is stripped of Juan entered the Carmelite Order there at everything, John realizes that the crucified the age of 21 under the name of Fray Juan and risen Christ has become his Everything. de San Matías (Brother John of Saint Mat- In August 1578, he managed to escape. He thias). Afterward, he studied theology in Sa- quickly reached Andalusia, where he lived lamanca where he was ordained a priest in ten fruitful years in missions, apostolate and 1567. On his return to Medina del Campo, he spiritual writing. met Teresa of Jesus, who had just founded At the age of 46, John is sent to Sego- a second monastery of Discalced Carmelites via with great responsibilities. But rivalries there, after she had established the one in emerge in the discalced Carmel and he is Avila. In this young religious, imbued with stripped of all authority. John asks to retire a great spiritual desire, she recognized the in solitude. -

Glasses of Wine Sparkling Wine

GLASSES OF WINE SPARKLING WINE CHAMPAGNE Germar Breton 19 Guillaume Sergent, Les Prés Dieu, Blanc de Blancs 2018 24 Charles Heidsieck, Réserve, Rosé 25 Krug, Grande Cuvée, 169ème Edition 45 SHERRY WINE FINO Equipo Navazos, Bota #54, Jerez de La Frontera 10 MANZANILLA Bodegas Barrero, Gabriela Oro en Rama, 9 Sanlúcar de Barrameda OLOROSO Emilio Hidalgo, Gobernador, Jerez de La Frontera 8 ROSÉ WINE SYRAH Château La Coste, Grand Vin, Coteaux d'Aix, 13 Provence, France 2020 MOURVÈDRE Château de Pibarnon, Bandol, Provence, France 2019 15 GLASSES OF WHITE WINE GRÜNER VELTLINER Weingut Jurtschitsch, Löss, Kamptal, Austria 2018 13 RIESLING Weingut Odinstal, Vulkan, Trocken, Pfalz, Germany 2018 29 CHENIN BLANC Domaine du Closel, La Jalousie, Savennières, 20 Loire Valley, France 2018 SAUVIGNON BLANC Vincent Pinard, Grand Chemarin, Sancerre, 22 Loire Valley, France 2018 TOCAI FRIULANO Massican, Annia, Napa Valley, California, 19 United States 2018 MARSANNE J.L. Chave Sélection, Blanche, Hermitage, 21 Rhône Valley, France 2016 SAVAGNIN Domaine de La Borde, Foudre à Canon, 17 Arbois-Pupillin, Jura, France 2018 CHARDONNAY Gérard Tremblay, Côte de Léchet, 15 Chablis Premier Cru, Burgundy, France 2018 Domaine Larue, Le Trézin, Puligny-Montrachet, 26 Burgundy, France 2018 Racines, Bentrock, Sta. Rita Hills, 38 California, United States 2017 GLASSES OF RED WINE GAMAY NOIR Jean-Claude Lapalu, Vieilles Vignes, Brouilly, 13 Beaujolais, France 2019 PINOT NOIR Domaine Alain Michelot, Vieilles Vignes, 25 Nuits-Saint-Georges, Burgundy, France 2015 Tyler, Dierberg, Block 5, Santa Maria Valley, 29 California, United States 2013 BLAUFRÄNKISCH Markus Altenburger, Leithaberg, Burgenland, 16 Austria 2017 CABERNET FRANC Domaine des Roches Neuves, Franc de Pied, 21 Saumur-Champigny, Loire Valley, France 2018 SYRAH René Rostaing, Ampodium, Côte-Rôtie, 27 Rhône Valley, France 2014 NEBBIOLO G.D. -

Julien Bourgeois Simulation of the Effect of Auxiliary Ties Used in the Construction of Mallorca Cathedral

Simulation of the effect of auxiliary ties used in the construction of Spain I 2013 Julien Bourgeois Mallorca Cathedral Cathedral construction ofMallorca auxiliary tiesusedinthe Simulation ofthe effect of Julien Bourgeois UNIVERSITÀ DEGLISTUDIDIPADOVA Julien Bourgeois Simulation of the effect of auxiliary ties used in the construction of Mallorca Cathedral Spain I 2013 Simulation of the effect of auxiliary ties used in the construction of Mallorca Cathedral DECLARATION Name: Bourgeois Email: [email protected] Title of the Simulation of the effect of auxiliary ties used in the construction of Mallorca Msc Dissertation: Cathedral Supervisor(s): Professor Luca Pelà Year: 2013 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. I hereby declare that the MSc Consortium responsible for the Advanced Masters in Structural Analysis of Monuments and Historical Constructions is allowed to store and make available electronically the present MSc Dissertation. University: Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya Date: July 18, 2013 Signature: Erasmus Mundus Programme ADVANCED MASTERS IN STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF MONUMENTS AND HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTIONS i Simulation of the effect of auxiliary ties used in the construction of Mallorca Cathedral This page is left blank on purpose. Erasmus Mundus Programme ii ADVANCED MASTERS IN STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF MONUMENTS AND HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTIONS Simulation of the effect of auxiliary ties used in the construction of Mallorca Cathedral ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Luca Pelà, for his strong implication concerning the present thesis. -

The Public Sphere and the East India Company

He, Dan (2019) Public State, Private Corporation : A Joint History of the Ideas of the Public/Private Distinction, the State, and the Corporation. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32467 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. PUBLIC STATE, PRIVATE CORPORATION - A Joint History of the Ideas of the Public/Private Distinction, the State, and the Corporation DAN HE Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2019 Department of Law SOAS, University of London 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENT ............................................................................ 5 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................... 6 I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... -

Géoarchéologie Du Site Antique De Molesme En Vallée De Laigne (Côte

Géoarchéologie du site antique de Molesme en vallée de Laigne (Côte-d’Or) : mise en évidence de l’impact anthropique sur la sédimentation alluviale Christophe Petit, Christian Camerlynck, Eline Deweirdt, Christophe Durlet, Jean-Pierre Garcia, Emilie Gauthier, Vincent Ollive, Hervé Richard, Patrice Wahlen To cite this version: Christophe Petit, Christian Camerlynck, Eline Deweirdt, Christophe Durlet, Jean-Pierre Garcia, et al.. Géoarchéologie du site antique de Molesme en vallée de Laigne (Côte-d’Or) : mise en évidence de l’impact anthropique sur la sédimentation alluviale. Gallia - Archéologie de la France antique, CNRS Éditions, 2006, 63, pp.263-281. 10.3406/galia.2006.3298. hal-01911071 HAL Id: hal-01911071 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01911071 Submitted on 8 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License GÉOARCHÉOLOGIE DU SITE ANTIQUE DE MOLES M E EN VA LLÉE DE LAIGNE (CÔTE -D’OR) Mise en évidence de l’impact anthropique sur la sédimentation alluviale Christophe PETIT 1, Christian CA M ERLYNCK 2, Eline DEWEIRDT 1, Christophe DURLET 3, Jean-Pierre GARCIA 3, Émilie GAUTHIER 4, Vincent OLLIVE 3, Hervé RICHARD 4, Patrice WAHLEN 5 Mots-clés. -

The Light from the Southern Cross’

A REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA IMPLEMENTATION ADVISORY GROUP AND THE GOVERNANCE REVIEW PROJECT TEAM REVIEW OF GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT OF DIOCESES AND PARISHES REPORT – STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Let us be bold, be it daylight or night for us - The Catholic Church in Australia has been one of the epicentres Fling out the flag of the Southern Cross! of the sex abuse crisis in the global Church. But the Church in Let us be fırm – with our God and our right for us, Australia is also trying to fınd a path through and out of this crisis Under the flag of the Southern Cross! in ways that reflects the needs of the society in which it lives. Flag of the Southern Cross, Henry Lawson, 1887 The Catholic tradition holds that the Holy Spirit guides all into the truth. In its search for the path of truth, the Church in Australia And those who are wise shall shine like the brightness seeks to be guided by the light of the Holy Spirit; a light symbolised of the sky above; and those who turn many to righteousness, by the great Constellation of the Southern Cross. That path and like the stars forever and ever. light offers a comprehensive approach to governance issues raised Daniel, 12:3 by the abuse crisis and the broader need for cultural change. The Southern Cross features heavily in the Dreamtime stories This report outlines, for Australia, a way to discern a synodal that hold much of the cultural tradition of Indigenous Australians path: a new praxis (practice) of church governance. -

Colleague, Critic, and Sometime Counselor to Thomas Becket

JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History–Doctor of Philosophy 2021 ABSTRACT JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter John of Salisbury was one of the best educated men in the mid-twelfth century. The beneficiary of twelve years of study in Paris under the tutelage of Peter Abelard and other scholars, John flourished alongside Thomas Becket in the Canterbury curia of Archbishop Theobald. There, his skills as a writer were of great value. Having lived through the Anarchy of King Stephen, he was a fierce advocate for the liberty of the English Church. Not surprisingly, John became caught up in the controversy between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, Henry’s former chancellor and successor to Theobald as archbishop of Canterbury. Prior to their shared time in exile, from 1164-1170, John had written three treatises with concern for royal court follies, royal pressures on the Church, and the danger of tyrants at the core of the Entheticus de dogmate philosophorum , the Metalogicon , and the Policraticus. John dedicated these works to Becket. The question emerges: how effective was John through dedicated treatises and his letters to Becket in guiding Becket’s attitudes and behavior regarding Church liberty? By means of contemporary communication theory an examination of John’s writings and letters directed to Becket creates a new vista on the relationship between John and Becket—and the impact of John on this martyred archbishop.