From Downton Abbey to Mad Men: Tv Series As the Privileged Format for Transition Eras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oktoberfest’ Comes Across the Pond

Friday, October 5, 2012 | he Torch [culture] 13 ‘Oktoberfest’ comes across the pond Kaesespaetzle and Brezeln as they Traditional German listened to traditional German celebration attended music. A presentation with a slideshow was also given presenting by international, facts about German history and culture. American students One of the facts mentioned in the presentation was that Germans Thomas Dixon who are learning English read Torch Staff Writer Shakespeare because Shakespearian English is very close to German. On Friday, Sept. 28, Valparaiso Sophomore David Rojas Martinez University students enjoyed expressed incredulity at this an American edition of a famous particular fact, adding that this was German festival when the Valparaiso something he hadn’t known before. International Student Association “I learned new things I didn’t and the German know about Club put on German and Oktoberfest. I thought it was English,” Rojas he event great. Good food, Martinez said. was based on the good people, great “And I enjoyed annual German German culture. the food – the c e l e b r a t i o n food was great.” O k t o b e r f e s t , Other facts Ian Roseen Matthew Libersky / The Torch the largest beer about Germany Students from the VU German Club present a slideshow at Friday’s Oktoberfest celebration in the Gandhi-King Center. festival in the Senior mentioned in world. he largest the presentation event, which takes place in included the existence of the Munich, Germany, coincided with Weisswurstaequator, a line dividing to get into the German culture. We c u ltu re .” to have that mix and actual cultural VU’s own festival and will Germany into separate linguistic try to do things that have to do with Finegan also expressed exchange,” Finegan said. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

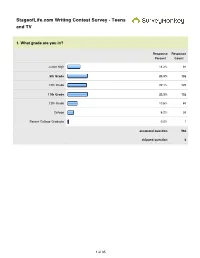

Stageoflife.Com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV

StageofLife.com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV 1. What grade are you in? Response Response Percent Count Junior High 14.3% 81 9th Grade 23.3% 132 10th Grade 22.1% 125 11th Grade 23.3% 132 12th Grade 10.6% 60 College 6.2% 35 Recent College Graduate 0.2% 1 answered question 566 skipped question 0 1 of 35 2. How many TV shows (30 - 60 minutes) do you watch in an average week during the school year? Response Response Percent Count 20+ (approx 3 shows per day) 21.7% 123 14 (approx 2 shows per day) 11.3% 64 10 (approx 1.5 shows per day) 9.0% 51 7 (approx. 1 show per day) 15.7% 89 3 (approx. 1 show every other 25.8% 146 day) 1 (you watch one show a week) 14.5% 82 0 (you never watch TV) 1.9% 11 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3. Do you watch TV before you leave for school in the morning? Response Response Percent Count Yes 15.7% 89 No 84.3% 477 answered question 566 skipped question 0 2 of 35 4. Do you have a TV in your bedroom? Response Response Percent Count Yes 38.7% 219 No 61.3% 347 answered question 566 skipped question 0 5. Do you watch TV with your parents? Response Response Percent Count Yes 60.6% 343 No 39.4% 223 If yes, which show(s) do you watch as a family? 302 answered question 566 skipped question 0 6. Overall, do you think TV is too violent? Response Response Percent Count Yes 28.3% 160 No 71.7% 406 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3 of 35 7. -

Downton Abbey Series Thre Tpb Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DOWNTON ABBEY SERIES THRE TPB PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Julian Fellowes | 420 pages | 11 Sep 2014 | HarperCollins | 9780007481545 | English | London, United Kingdom DOWNTON ABBEY SERIES THRE TPB PDF Book Edith's wedding day arrives, but as Edith reaches the altar, Sir Anthony Strallan changes his mind and calls off the ceremony. At the Hospital Meeting uncredited 1 episode, Looking forward to the arrival of season 3! Read on…. Prisoner uncredited 1 episode, She married a Commoner. Best Man uncredited 1 episode, Kiernan Branson 1 episode, Jamie de Courcey The servants ball is a wild success. Davis 2 episodes, Henry Talbot 7 episodes, In spite of Mrs Hughes, Mrs Patmore and Carson's attempts to keep the peace, romantic tensions below stairs cause problems. Never fear, though! Duke of Crowborough 1 episode, Alun Armstrong Carson is exhausted and gains a new respect for his wife's efforts. Stretcher Bearer 1 episode, Stephen Omer Most of the staff are dismissive of her aspirations but the family - except Violet of course - are supportive and youngest daughter Sybil offers to supply a reference. Branson comes to a heart-wrenching decision, and the storm clouds that have been gathering over Anna and Bates finally burst. Thomas' condition deteriorates, prompting him to finally reveal the truth to Baxter. Retrieved 6 November Mavis 1 episode, King George V 1 episode, It is a guide to the show's characters through the early part of the third series. Isobel announces her marriage at dinner. Countess Violet is exceedingly witty. Injured Officer uncredited 1 episode, Cara Bamford Lawyer uncredited 1 episode, Anna, feeling unworthy of Bates, grows distant and moves back into the main house. -

Gosford Park, the ”Altmanesque” and Narrative Democracy’ James Dalrymple

’Gosford Park, the ”Altmanesque” and Narrative Democracy’ James Dalrymple To cite this version: James Dalrymple. ’Gosford Park, the ”Altmanesque” and Narrative Democracy’. ”Narrative Democ- racy in 20th- and 21st-Century British Literature and Visual Arts”, SEAC 2018 conference, Nov 2018, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, France. hal-01911889 HAL Id: hal-01911889 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01911889 Submitted on 25 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. James Dalrymple (ILCEA4) – Gosford Park, the ‘Altmanesque’ and democracy Gosford Park, the ‘Altmanesque’ and democracy James Dalrymple, Institut des langues et cultures d'europe, amérique, afrique, asie et australie (ILCEA4), Université Grenoble-Alpes, France. Often working with large casts of actors—and many featuring on screen simultaneously, with dialogues frequently overlapping one another and given little hierarchy in the sound design—US director Robert Altman (1925–2006) came to be associated with a signature style despite working in a range of genres, mostly in order to subvert their conventions. The adjective ‘Altmanesque’ has come to apply to this aesthetic, one in which much is also left to chance, with actors given space to improvise and create their own characters within a larger tableau or ‘mural’ (del Mar Azcona 142). -

COVID Update 1.8.21 and Channel 1970 1.10

To: Dunwoody Village Residents, Families and Staff From: Kathy Barton, Director of Operations Brandon Jolly, Director of Health Services Re: CONTINUED UPDATE RE: COVID-19 January 8, 2021 General Updates: Care Center Updates: Vaccines - CVS Pharmacy is scheduled to be on-site at Dunwoody Village on 1/14/21 to begin vaccinating Care Center residents and staff. Today I received notice that our second on-site vaccine clinic is scheduled for 2/9/21. County Positivity Rate: Delaware County’s Covid-19 Positivity Rate remains above 10%, currently at 11.0% as of 1/4/2021. Although it is dropping, Delaware County will remain in a “red-level” of risk for Covid-19 until the County positivity rate drops below 10%. Status of Positive Cases: We currently have a total of (13) Covid positive residents in the skilled center on all four units: Dundale, Pavilion, Patten and Fairlee. 5 residents have finished their 14- day quarantine and have recovered. Over this weekend, we will have 5 more residents complete their 14-day Quarantine. The units are closed to all access, except for essential staff needed to provide care to residents on the units. All units are currently under strict infection control precautions. No new residents in personal care have tested positive since December 23, 2020. In the past week we have had 6 staff test positive for Covid. 2 have some symptoms and 4 are asymptomatic. They are all quarantined at home. We also have 12 staff that are out due to being exposed with close personal contact to someone that tested positive to Covid or with symptoms of Covid. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

1 Nominations Announced for the 19Th Annual Screen Actors Guild

Nominations Announced for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Ceremony will be Simulcast Live on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2013 on TNT and TBS at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) LOS ANGELES (Dec. 12, 2012) — Nominees for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® for outstanding performances in 2012 in five film and eight primetime television categories as well as the SAG Awards honors for outstanding action performances by film and television stunt ensembles were announced this morning in Los Angeles at the Pacific Design Center’s SilverScreen Theater in West Hollywood. SAG-AFTRA Executive Vice President Ned Vaughn introduced Busy Philipps (TBS’ “Cougar Town” and the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® Social Media Ambassador) and Taye Diggs (“Private Practice”) who announced the nominees for this year’s Actors®. SAG Awards® Committee Vice Chair Daryl Anderson and Committee Member Woody Schultz announced the stunt ensemble nominees. The 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® will be simulcast live nationally on TNT and TBS on Sunday, Jan. 27 at 8 p.m. (ET)/5 p.m. (PT) from the Los Angeles Shrine Exposition Center. An encore performance will air immediately following on TNT at 10 p.m. (ET)/7 p.m. (PT). Recipients of the stunt ensemble honors will be announced from the SAG Awards® red carpet during the tntdrama.com and tbs.com live pre-show webcasts, which begin at 6 p.m. (ET)/3 p.m. (PT). Of the top industry accolades presented to performers, only the Screen Actors Guild Awards® are selected solely by actors’ peers in SAG-AFTRA. -

The War Against the Kitchen Sink Pilot

The War Against the Kitchen Sink Pilot Another way to describe “The War Against the Kitchen Sink Pilot” would be: “How to Overcome the Premise Pilot Blues.” A premise pilot literally establishes the premise of the show. Often they’re expository—it’s Maia’s first day at Diane’s law firm; the first time Mulder and Scully are working together; the day Cookie gets out of prison; when Walt decides he’s going to cook meth and potentially deal drugs. Premise pilots generally reset everything. When they work well, the creators take their time establishing the introduction into the world. We get the launch of the series in a nuanced, layered, slow burn way. I’m more satisfied by a pilot that has depth; there’s time for me to get to know the characters before throwing me into a huge amount of plotting. For me, character is always more important than plot. Once the characters are established, I’ll follow them anywhere. In 1996, when John Guare, the smart, prolific, outside-the-box playwright and screenwriter, published his first volume of collected works, he wrote a preface for the book The War Against the Kitchen Sink. One of the things Guare was rallying against was that desperate perceived need for realism, such as of drab objects in plays, when they could only ever be a construct. More interested in inner realities, !1 he grew curious in musicals, because there is no fourth wall. The actors interact with the audience, and Guare was intrigued by the connection between the audience and the actors on stage. -

The World of Downton Abbey, September 2013

The World of Downton Abbey A Tour to England with WFSU! September 12 - 21, 2013 Limited to 25 participants An exclusive presentation by WFSU Highclere Castle TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Join WFSU for a truly memorable trip to England this fall! • Invitation to a charity event with Lord and Lady Carnarvon at Highclere Masterpiece’s Downton Abbey has seduced audiences both in Castle, location for exterior and interior scenes of Downton Abbey Britain and here, “across the pond”, by its superbly crafted script • Dinner at Byfleet Manor, location of the Dowager Countess’s home of simmering sub plots and four dimensional characters, deftly • Private guides, talks and visits with experts on British history and the portrayed, upstairs and down, by an unforgettable cast. On a Edwardian era in particular tour of historic England, we will discover what makes this world • Tours of major historical sites in London, Oxford and Bath, including the so fascinating in fact and fiction, past and present. The highlight House of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, Blenheim Palace, Oxford, its University and Colleges, Lacock Abbey, and Bampton village (Downton will be attending a private charity event at Highclere Castle: for village scenes), among others more than 300 years the home of Lord and Lady Carnarvon, the • Prime tickets to a performance of Hamlet in Stratford, plus evensong in real Downton Abbey. Oxford • Deluxe 4-star accommodations in London, Oxford, and Ston Easton, From Edwardian London and the iconic Houses of Parliament, to near Bath the Georgian splendour of Jane Austen’s Bath and the hallowed • Private, air-conditioned motorcoach transportation to all destinations in halls of Oxford, invited scholars and expert guides will help us the itinerary explore our enduring fascination with the aristocracy, their grand • Free time for additional sight-seeing, shopping or relaxing estates, and how they survive today. -

MASTERPIECE CLASSIC "Downton Abbey, Season 2"

The Best Miniseries of 2011 Returns DowntonWinner of six PrimetimeAbbey Emmy® Season Awards 2 Sundays, January 8 through February 19, 2012, at 9pm ET on PBS One of the most phenomenally popular series in MASTERPIECE history is back for an exciting second season: Downton Abbey Season 2 resumes its story of love and intrigue at an English country estate, now mobilized for the trauma of war. With a returning cast including Dame Maggie Smith, Elizabeth McGovern, Hugh Bonneville, Dan Stevens, Michelle Dockery, Siobhan Finneran, and many more, Downton Abbey Season 2 airs over seven weeks from Sunday, January 8 through February 19, 2012, at 9pm ET on PBS (check local listings). For viewers who need to catch up on the doings at Downton—either because they missed the first season or want to watch it again—MASTERPIECE is re-airing Downton Abbey on Sundays, December 18 - January 1. Downton Abbey, produced by Carnival Films and co-produced by MASTERPIECE, was recently honored in the US with an impressive six Primetime Emmy® awards, including Outstanding Miniseries or Movie, plus awards for Supporting Actress Dame Maggie Smith, Writer Julian Fellowes, and nods for Directing, Cinematography, and Costumes. American critics raved, calling Downton Abbey “an instant classic” (New York Times), “compulsively watchable from the get-go” (Variety), “impossible to resist” (Wall Street Journal), “addictive” (People Magazine), “the best Abbey since Abbey Road” (Entertainment Weekly), and “a quintessential Masterpiece Classic” (TV Guide). “MASTERPIECE viewers took Downton Abbey to heart and they won’t be disappointed with season two,” says MASTERPIECE Executive Producer Rebecca Eaton. -

KAREN RADZIKOWSKI 1St Assistant Director

KAREN RADZIKOWSKI st 1 Assistant Director Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. BILLIONS (seasons 5-6) Various Showtime EP: Brian Koppelman, David Levien, Andrew Ross Sorkin COLIN IN BLACK & WHITE (season 1) Ava DuVernay Netflix NY Unit EP: Ava DuVernay, Colin Kaepernick / Prod: Lyn Pinezich FBI: MOST WANTED (season 1) Various CBS / Universal Television EP: Dick Wolf, Arthur Forney, Peter Jankowski / Prod: Tom Sellitti ALTERNATINO (season 1) Various Comedy Central / Avalon Television EP: Jay Martel, Arturo Castro / Prod: Ayesha Rokadia AT HOME WITH AMY SEDARIS (seasons 1-2) Various truTV / A24 2018 + 2019 Emmy Nomination: Outstanding Variety/Sketch Series EP: Paul Dinello, Vernon Chatman, John Lee / Prod: Inman Young GOATFACE (variety/sketch) Asif Ali Comedy Central Cast: Hasan Minhaj EP: Asif Ali, Fahim Anwar / Prod: Steve Ast MARVEL’S IRON FIST (season 2) Various Netflix / Marvel Studios ep. 213 | tandem unit: ep. 204, 206 | 2nd unit: ep. 207 EP: Jim Chory, Dan Buckley / Prod: Lyn Pinezich RAMY (pilot presentation) Harry Bradbeer Hulu / A24 World Premiere: SXSW Film Festival EP: Jerrod Carmichael, John Hodges, Ravi Nandan Prod: Jamin O’Brien THE BREAKS (season 1) Various VH1 / Atlantic Pictures EP: Susan Levison, Bill Flanagan / Prod: Gary Giudice BALLERS (seasons 1-2) Simon Cellan Jones HBO EP: Dennis Biggs / Prod: Karyn McCarthy BURN NOTICE (2nd unit) Artie Malesci USA / Fox Television Studios EP: Terry Miller MAGIC CITY (season 1) Various Starz / Media Talent Group EP: Mitch Glazer, Ed Bianchi UNITED STATES OF TARA (season 3) Various Showtime / Dreamworks Television EP: Craig Zisk, Brett Baer, Dave Finkel / Prod: Dan Kaplow MAD MEN (2nd unit, season 4) Various AMC / Lionsgate Television EP: Matthew Weiner, Scott Hornbacher WARREN THE APE (season 1) Various MTV / MTV Productions EP: Kevin Chinoy GREG THE BUNNY (season 1) Various Fox / 20th Century Fox Television EP: Kevin Chinoy Features PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO.