Whistleblower Retaliation at the Fbi: Improving Protections and Oversight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims: What Employers Need to Know

Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims: What Employers Need to Know May 6, 2020 Presenters Steven J. Pearlman Lloyd B. Chinn Harris M. Mufson Pinchos (Pinny) Goldberg Partner (Chicago) Partner (New York) Partner (New York) Associate (New York) T: +1.312.962.3545 T:+1.212.969.3341 T: +1.212.969.3794 T: +1.212.969.3074 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims May 6, 2020 COVID-19 Wrongful Death Suit: Evans v. Walmart • First known COVID-19 wrongful death suit - filed in Illinois • Decedent contracted COVID-19 while working at a Walmart store ‒ Another employee who worked at the store died of COVID-19 shortly after the decedent • Complaint alleges: ‒ Walmart failed to implement safety measures recommended by CDC/OSHA ‒ Management did not clean and sterilize the store, provide employees with PPE, or implement social distancing ‒ Walmart did not bar employees with symptoms of COVID-19 ‒ Walmart did not warn employees that other workers had COVID-19 3 Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims May 6, 2020 Whistleblower/Retaliation Claims on the Rise • Reports of employees alleging retaliation for reporting lack of safety measures and personal protective equipment (“PPE”) ‒ Health care workers ‒ Warehouse employees • 1,000+ OSHA complaints regarding lack of COVID-19 protections • OSHA Press Release “reminding employers that it is illegal to retaliate against workers because they report unsafe and unhealthful working conditions during the coronavirus” -

Employee Onboarding

Strategic Onboarding: The Effects on Productivity, Engagement, & Turnover By: Lisa Reed, MBA, SPHR Onboarding Defined A systematic and comprehensive approach to integrating a new employee with an employer and its culture, while also ensuring the employee is provided with the tools and information necessary to becoming a productive member of the team (1). How Important is Onboarding? 43% of employees state the opportunity for advancement was the key factor in deciding whether or not to stay with an organization, and the onboarding process, or lack thereof, was a main factor in determining advancement potential within a company (2). EMPLOYEE PRODUCTIVITY What is Employee Productivity? An assessment of the efficiency of a worker or group of workers, which is typically compared to averages, is referred to as employee productivity (3). Costs of Employee Unproductivity More than $37 billion dollars annually is spent by organizations in the US to keep unproductive employee in jobs they do not understand (4). What Effect Does Strategic Onboarding Have On Employee Productivity? Only 49% of new employees without formal onboarding meet their first performance milestone (5). In contrast, 77% of employees who are provided with a formal onboarding process meet first performance milestones (6). Employee performance can increase by 11% with an effective onboarding process, which can also be linked to a 20% increase in an employee’s discretionary effort (7). EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT What is Employee Engagement? Employee engagement describes the way employees show a logical and emotional commitment to their work, team, and organization, which in turn drives their discretionary effort. Costs of Employee Disengagement Actively disengaged employees are more likely to steal, miss work, and negatively influence other workers and cost the United States up to $550 billion annually in lost resources and productivity (8). -

Data Sheet: Oracle Recruiting Cloud

Oracle Recruiting Finding the best talent, hiring them quickly and onboarding them efficiently, can be difficult in today’s competitive environment. Oracle Recruiting (part of Oracle Cloud HCM) addresses these common challenges of recruiting and takes this process into the modern era by leveraging a data-driven approach and a mobile user interface (UI) to Key features source and engage both internal and external • Requisition management • Career page design templates candidates, and apply business insights across • Mobile-responsive UI all of HCM for better hiring decisions. • Extensible branding and multimedia support • Job search and discovery INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY TO KEEP CANDIDATES AT • Candidate pools THE CENTER OF THE RECRUITING PROCESS • Adaptive intelligence Savvy organizations use technology to stay ahead of the competition when it comes • Native recruiting to attracting and retaining top talent. HR leaders are being tasked with broadening • End-to-end sourcing, recruiting, their approach to Human Capital Management, incorporating concepts and practices and offers that were once the primary domain of marketing, legal, or chief executives. The • Unified architecture and tooling practice of HR is also transforming from being a mere cost center to a value • Multichannel sourcing generator, driving business growth through holistic talent development. HR is evolving to increasingly leverage technology to improve efficiency and provide • Conversational interactions via insight into an organization’s most valuable source of productivity. Organizations use digital assistant this insight to help leaders understand success parameters and their organization’s • Proven third-party extensions talent capabilities. • Advanced reporting and analytics Oracle Recruiting is a new recruiting solution delivered natively as part of Oracle • Unified self-service interface Cloud HCM. -

Intentional Disregard: Trump's Authoritarianism During the COVID

INTENTIONAL DISREGARD Trump’s Authoritarianism During the COVID-19 Pandemic August 2020 This report is dedicated to those who have suffered and lost their lives to the COVID-19 virus and to their loved ones. Acknowledgments This report was co-authored by Sylvia Albert, Keshia Morris Desir, Yosef Getachew, Liz Iacobucci, Beth Rotman, Paul S. Ryan and Becky Timmons. The authors thank the 1.5 million Common Cause supporters whose small-dollar donations fund more than 70% of our annual budget for our nonpartisan work strengthening the people’s voice in our democracy. Thank you to the Common Cause National Governing Board for its leadership and support. We also thank Karen Hobert Flynn for guidance and editing, Aaron Scherb for assistance with content, Melissa Brown Levine for copy editing, Kerstin Vogdes Diehn for design, and Scott Blaine Swenson for editing and strategic communications support. This report is complete as of August 5, 2020. ©2020 Common Cause. Printed in-house. CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................ 3 President Trump’s ad-lib pandemic response has undermined government institutions and failed to provide states with critically needed medical supplies. .............5 Divider in Chief: Trump’s Politicization of the Pandemic .................................... 9 Trump has amplified special interest-funded “liberate” protests and other “reopen” efforts, directly contradicting public health guidance. ...................9 Trump and his enablers in the Senate have failed to appropriate adequate funds to safely run this year’s elections. .........................................11 President Trump has attacked voting by mail—the safest, most secure way to cast ballots during the pandemic—for purely personal, partisan advantage. ..............12 The Trump administration has failed to safeguard the health of detained and incarcerated individuals. -

Leading Remote Teams Provided By: Taggart Insurance

Leading Remote Teams Provided by: Taggart Insurance This HR Toolkit is not intended to be exhaustive nor should any discussion or opinions be construed as legal advice. Readers should contact legal counsel for legal advice. © 2020 Zywave, Inc. All rights reserved. Leading Remote Teams | Provided by: Taggart Insurance Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................4 Remote Work Planning ................................................................................................5 Schedules .....................................................................................................5 Technology ....................................................................................................5 Employee Workstation ..................................................................................5 Policies ..........................................................................................................6 Interviewing and Onboarding .......................................................................6 Virtual Interviewing ................................................................6 Remote Onboarding ..............................................................7 Company Culture in the Remote Workplace ...............................................................9 What Is Company Culture? ..........................................................................9 Strong Company Culture.............................................................................. -

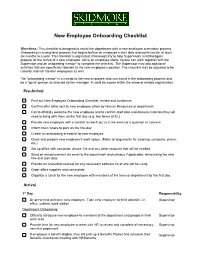

New Employee Onboarding Checklist

New Employee Onboarding Checklist Directions: This checklist is designed to assist the department with a new employee orientation process. Onboarding is a long-term process that begins before an employee’s start date and continues for at least six months to a year. This checklist is organized chronologically to help Supervisors and Managers prepare for the arrival of a new employee. Once an employee starts, he/she can work together with the Supervisor and an onboarding mentor* to complete the checklist. The Supervisor may add additional activities that are specifically relevant to the new employee’s position. The checklist may be adjusted to be used for internal transfer employees as well. *An "onboarding mentor" is a mentor to the new employee who can assist in the onboarding process and be a “go-to” person as directed by the manager. It could be a peer within the same or related organization. Pre-Arrival Print out New Employee Onboarding Checklist, review and customize Confirm offer letter sent to new employee either by Human Resources or department Call to officially welcome the new employee and to confirm start date and discuss materials they will need to bring with them on the first day (e.g. two forms of ID.) Provide new employee with a contact to reach out to in the event of a question or concern Inform them where to park on the first day Create an onboarding schedule for new employee Clean and prepare new employee's work space. (Make arrangements for cleaning, computer, phone, etc.) Set up office with computer, phone, file and any other resource that will be needed Send an announcement via email to the department and campus if applicable, announcing the new hire and start date Provide an instruction manual for any necessary software he or she will be using Order office supplies and name plate Organize a lunch for the new employee with members of the team or department for the first day Arrival 1st Day Responsibility Be present to welcome new employee. -

Region Ix Whistleblower Protection Program Complaints Were Not Complete Or Timely

REPORT TO THE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION REGION IX WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION PROGRAM COMPLAINTS WERE NOT COMPLETE OR TIMELY DATE ISSUED: NOVEMBER 23, 2020 REPORT NUMBER: 02-21-001-10-105 To answer all of these questions, we: 1) tested U.S. Department of Labor a sample of whistleblower complaints from Office of Inspector General October 1, 2010, through September 30, 2018; Audit 2) conducted interviews in Region IX to determine if OSHA provided investigators with appropriate operational resources; and 3) reviewed 15 WPP cases and 77 allegations provided by the Whistleblower. BRIEFLY… We also followed up on recommendations from prior audits to determine if OSHA had successfully implemented corrective actions. REGION IX WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION PROGRAM COMPLAINTS WERE NOT COMPLETE OR TIMELY WHAT OIG FOUND We found no evidence of misconduct, nor November 23, 2020 evidence of any other issue that would rise to the level of “violations of law, rule, or regulation WHY OIG CONDUCTED THE AUDIT and gross mismanagement.” However, we did On July 6, 2018, then Secretary of Labor find problems with the completeness and Alexander Acosta received a referral from the timeliness of investigations into whistleblower U.S. Office of Special Counsel (OSC) that complaints, as 96 percent of those sampled did described allegations against the Occupational not meet all essential elements and 88 percent Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) of cases exceeded statutory timeframes for Whistleblower Protection Program (WPP). investigations by an average of 634 days. WPP investigates complaints of employer These results were worse than the results we retaliation when employees report violations of reported in 2010 and 2015 audits, and could be law by their employers. -

Strawbery Banke Museum Employee Handbook

Strawbery Banke Museum EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK Updated: June 4, 2021 TABLE of CONTENTS CORE POLICIES Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.0 WELCOME 4 1.1 A Welcome Policy 4 1.2 At-Will Employment 4 2.0 INTRODUCTORY LANGUAGE AND POLICIES 5 2.1 About the Organization 5 2.2 Organization Facilities 5 2.3 Ethics Code 5 2.4 Strategic Framework, Mission, and Vision Statements 6 2.5 Categories of Employment 6 2.6 Revisions to Handbook 7 3.0 HIRING AND ORIENTATION POLICIES 7 3.1 Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Statement and Anti-Harassment Policy 7 3.2 Conflicts of Interest 9 3.3 Employment of Relatives and Friends 11 3.4 Job Descriptions 11 3.5 Training Program 11 3.6 Employment Authorization Verification 11 3.7 Disability Accommodation 12 3.8 Religious Accommodation 12 4.0 WAGE AND HOUR POLICIES 12 4.1 Attendance Policy 12 4.2 Job Abandonment 13 4.3 Business Expenses Policy 13 4.4 Travel Expenses 13 4.5 Introduction to Wage and Hour Policies 15 4.6 Pay Period 15 4.7 Recording Time 15 4.8 Overtime 16 4.9 Required Annual Special Events Policy for Year-Round Employees 17 4.10 Travel Time Pay 18 4.11 Meal and Rest Periods Policy 19 4.12 Accommodations for Nursing Parents 19 4.13 Paycheck Deductions 20 4.14 Direct Deposit 20 4.15 On Call 20 4.16 Use of Employer Credit Cards 20 4.17 Wage Disclosure Protection 21 5.0 PERFORMANCE, DISCIPLINE, LAYOFF, AND TERMINATION 21 5.1 Standards of Conduct 21 5.2 Open Door / Conflict Resolution Policy 22 5.3 Pay Raises 22 5.4 Performance Evaluation and Improvement Plans 22 5.5 Disciplinary Process 23 5.6 Criminal Activity -

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace

Position on Providing a Discrimination-Free Workplace Background A discrimination-free workplace is one in which employees are attracted, recruited, assigned to work, provided with training and development, promoted and remunerated on the basis of their capabilities. It signals that no distinction, exclusion or preference relating to an individual’s employment is made on grounds other than the ability or potential ability of an individual to meet required job needs. Discrimination-free means equal opportunity for all, irrespective of non-work-related personal characteristics. Further, it means actively advancing practices that promote equity by, for example, assuring inclusive selection criteria to more fully reach qualified persons. Discrimination in any form is harmful to society, individuals, and the conduct of business. By definition, discrimination prevents individuals from realizing their human rights and from fully and productively participating in society and/or business activity. The achievement of a prosperous society depends on all individuals being treated with dignity and respect. The achievement of sustainable business equally depends on individuals attaining employment in a workplace that values them and their unique qualities. Relevance As the largest and most broadly based healthcare company in the world, Johnson & Johnson has a considerable impact on the lives of many individuals whom we directly employ, and this includes providing a workplace in which employees can feel valued, safe and free from discrimination. We believe that fostering an open and inclusive work environment, in which we value contributions from individuals of all backgrounds and experiences, is not only the right thing to do, it gives us the best chance of being able to work together to advance our mission of profoundly changing the trajectory of health for humanity. -

In the United States District Court for the Southern District of ______

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF _________ Attorney General of the State of ______ , on Behalf of the Citizens of the State of _____ Plaintiffs, Case No.: v. DONALD J. TRUMP Defendant. INTRODUCTION 1. This is a civil action for damages under the laws of the United State, common and general law, and international law for among other grounds, criminal negligence, wrongful death, gross negligence and willful misconduct, fraudulent concealment, dereliction of duty, crimes against humanity, treason and declaratory relief. 2. This action arises from Trump’s conduct prior to, during, and following the Covid-19 pandemic that swept through the country in 2020 and 2021. This lawsuit is based on Defendant Trump’s intentional, reckless, and/or negligent acts which caused inter alia: (a.) The deaths of 25,190 [insert name of state, county or municipality]; (b.) The infection of 419,642 [insert name of state, county or municipality] citizens; (c.) Life-long debilitating health conditions for tens of thousands; (d.) Loss of parents, grandparents, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters; (e) Economic losses and hardship for millions; and (f) Loss of property, including businesses, colleges and hospitals, JURISDICTION AND VENUE 3. Jurisdiction of this matter is founded upon diversity of citizenship under 28 U.S.C. § 1332 and pendent and concurrent state jurisdiction. 4. This Court has jurisdiction over this class action: under 28 U.S.C. § 1332, because the matter in controversy exceeds $75,000, exclusive of interest and costs, and because there is complete diversity of parties; under 28 U.S.C. -

Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Policy

Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Policy Effective Date: February 15, 2018 Last Revision: August 22, 2020 Owner: Chief Security Officer Approved By: Ivanti Security Council and Executive Leadership Internal Use Only Page 1 of 5 Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Policy Anti-Slavery and Human Trafficking Policy Effective Date: February 15, 2018 Last Revision: August 22, 2020 Owner: Chief Security Officer Approved By: Ivanti Security Council and Executive Leadership Applicable Country: Global 1.0 Overview and Purpose Ivanti is committed to high standards of corporate governance, and a key element of this is managing the business in a socially responsible way. Ivanti aims to employ the highest ethical and professional standards as we comply with local laws and regulations applicable to our business. As such, Ivanti is committed to preventing slavery and human trafficking in its corporate activities and its supply chains. This commitment to ethical and professional behavior is enforced and emphasized in our company policies and training programs. Ivanti expects the third-parties, parties such as suppliers and customers, to behave in a similar manner. This Policy is not intended to impose unnecessary restrictions that are contrary to Ivanti’s established culture of openness, trust, and integrity. Ivanti and its senior management are committed to protecting Ivanti's employees, partners, and the company from illegal or damaging actions, that happen either knowingly or unknowingly. They are also committed to protecting Ivanti’s information technology resources, brand, intellectual property, personal information, and customer data from misuse or compromise. Ivanti is committed to following all applicable laws and regulations. This Policy helps ensure the security of Ivanti’s Information Systems, including information that Ivanti may gather and store, such that it meets or exceeds industry standards. -

Mentor Onboarding Guide

MENTOR ONBOARDING GUIDE Everyone remembers how difficult the first few weeks on a new job can be. Those initial experiences went a long way in determining how quickly you became an effective, fully contributing member of our agency. Now, it is your turn to help ensure that our new employee’s first days and months on the job provide a successful launch to their career. You are responsible for helping the employee get settled into the agency, their workplace, and the local area. Being a mentor is not a substitute for the supervisor, but is someone who can answer the new employee’s questions about the work environment and the workplace culture in a positive and encouraging way. Your basic role is to meet with the new employee regularly and be available to answer questions, provide resources and insights about the agency. You will be their “go to” person and be available to help them find their way around at work. You can expect to serve as a mentor for around the first 3 months from the time they start with our agency. You are one of the keys to the success of the new employee during the onboarding process. WHY HAVE I BEEN SELECTED? You are an experienced employee and have demonstrated excellent performance and have good people skills. You have the demonstrated ability to build trust with the new employee, and are familiar with our high performance culture and agency mission and vision. You “know the ropes” and are an effective source of advice and encouragement. Selection Criteria Used Demonstrates high performance.