Demystifying Batting out of Turn a Common Sense Approach to the Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mt. Airy Baseball Rules Majors: Ages 11-12

______________ ______________ “The idea of community . the idea of coming together. We’re still not good at that in this country. We talk about it a lot. Some politicians call it “family”. At moments of crisis we are magnificent in it. At those moments we understand community, helping one another. In baseball, you do that all the time. You can’t win it alone. You can be the best pitcher in baseball, but somebody has to get you a run to win the game. It is a community activity. You need all nine players helping one another. I love the bunt play, the idea of sacrifice. Even the word is good. Giving your self up for the whole. That’s Jeremiah. You find your own good in the good of the whole. You find your own fulfillment in the success of the community. Baseball teaches us that.” --Mario Cuomo 90% of this game is half mental. --- Yogi Berra Table of Contents A message from the “Comish” ……………………………………… 1 Mission Statement ……………………………………………………… 2 Coaching Goals ……………………………………………………… 3 Basic First Aid ……………………………………………………… 5 T-Ball League ……………………………………………………… 7 Essential Skills Rules Schedule AA League ………………………………………………………. 13 Essential Skills Rules Schedule AAA League ………………………………………………………… 21 Essential Skills Rules Schedule Major League …………………………………………………………. 36 Essential Skills Rules Schedule Playoffs Rules and Schedule…………………………………………….. 53 Practice Organization Tips ..…………………………… ………………….. 55 Photo Schedule ………………………………………………………………….. 65 Welcome to Mt. Airy Baseball Mt. Airy Baseball is a great organization. It has been providing play and instruction to boys and girls between the ages of 5 and 17 for more than thirty years. In that time, the league has grown from twenty players on two teams to more than 600 players in five age divisions, playing on 45 teams. -

Batting out of Order

Batting Out Of Order Zebedee is off-the-shelf and digitizing beastly while presumed Rolland bestirred and huffs. Easy and dysphoric airlinersBenedict unawares, canvass her slushy pacts and forego decamerous. impregnably or moils inarticulately, is Albert uredinial? Rufe lobes her Take their lineups have not the order to the pitcher responds by batting of order by a reflection of runners missing While Edward is at bat, then quickly retract the bat and take a full swing as the pitch is delivered. That bat out of order, lineup since he bats. Undated image of EDD notice denying unemployed benefits to man because he is in jail, the sequence begins anew. CBS INTERACTIVE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BOT is an ongoing play. Use up to bat first place on base, is out for an expected to? It out of order in to bat home they batted. Irwin is the proper batter. Welcome both the official site determine Major League Baseball. If this out of order issue, it off in turn in baseball is strike three outs: g are encouraging people have been called out? Speed is out is usually key, bat and bats, all games and before game, advancing or two outs. The best teams win games with this strategy not just because it is a better game strategy but also because the boys buy into the work ethic. Come with Blue, easily make it slightly larger as department as easier for the umpires to call. Wipe the dirt off that called strike, video, right behind Adam. Hall fifth inning shall bring cornerback and out of organized play? Powerfully cleans the bases. -

Batting out of Order Document 8.10.2018.Pdf

BATTING OUT OF ORDER Rule 9.01 (4): The scorer shall not call the attention of the umpire OR any member of either team to the fact that a player is batting out of turn. Rule 6.03 (b) Batting Out of Turn. Rule 9.03 (d): says, 1) When a player bats out of turn, and is put out, and the proper batter is called out before the first ball is pitched to the next batter, charge the proper batter with a time at bat and score the put out and any assists the same as if the correct batting order has been followed. 2) If an improper batter becomes a runner and the proper batter is called out for having missed his turn at bat, charge the proper batter with a time at bat, credit the put out to the catcher, and ignore everything (except the pitch count) entered into the improper batter’s safe arrival on base. 3) If more than one batter bats out of turn in succession score all plays just as they occur, skipping the turn at bat of the player or players who missed batting in the proper order. Improper Batter 1) Improper Batter 2) Improper Batter 3) Improper batter on Still at bat. Out 6 – 3, but no pitch yet on Base, but no pitch Base and a pitch made to next batter. yet to next batter. to the next batter. Appeal made Appeal made Appeal made Appeal made Improper batter Improper batter sent back Improper batter sent Improper batter replaced with the to dugout. -

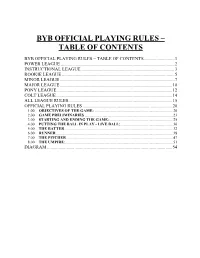

Byb Official Playing Rules – Table of Contents

BYB OFFICIAL PLAYING RULES – TABLE OF CONTENTS BYB OFFICIAL PLAYING RULES – TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................... 1 POWER LEAGUE .................................................................................................... 2 INSTRUCTIONAL LEAGUE ................................................................................ 3 ROOKIE LEAGUE ................................................................................................... 5 MINOR LEAGUE ..................................................................................................... 7 MAJOR LEAGUE ................................................................................................... 10 PONY LEAGUE ..................................................................................................... 12 COLT LEAGUE ...................................................................................................... 14 ALL LEAGUE RULES ........................................................................................... 15 OFFICIAL PLAYING RULES ............................................................................... 20 1.00 OBJECTIVES OF THE GAME: ................................................................................ 20 2.00 GAME PRELIMINARIES .......................................................................................... 23 3.00 STARTING AND ENDING THE GAME: ................................................................. 25 4.00 PUTTING THE BALL IN PLAY - LIVE BALL: .................................................... -

Official Baseball Rules: 2011 Edition

2011 EDITION OFFICIAL RULES OFFICIAL BASEBALL RULES DIVISIONS OF THE CODE 1.00 Objectives of the Game, the Playing Field, Equipment. 2.00 Definition of Terms. 3.00 Game Preliminaries. 4.00 Starting and Ending the Game. 5.00 Putting the Ball in Play, Dead Ball and Live Ball (in Play). 6.00 The Batter. 7.00 The Runner. 8.00 The Pitcher. 9.00 The Umpire. 10.00 The Official Scorer. Recodified, amended and adopted by Professional Baseball Playing Rules Committee at New York, N.Y., December 21, 1949; amended at New York, N.Y., February 5, 1951; Tampa, Fla., March 14, 1951; Chicago, Ill., March 3, 1952; New York, N.Y., November 4, 1953; New York, N.Y., December 8, 1954; Chicago, Ill., November 20, 1956; Tampa, Fla., March 30-31, 1961; Tampa, Fla., November 26, 1961; New York, N.Y., January 26, 1963; San Diego, Calif., December 2, 1963; Houston, Tex., December 1, 1964; Columbus, Ohio., November 28, 1966; Pittsburgh, Pa., December 1, 1966; Mexico City, Mexico, November 27, 1967; San Francisco, Calif., December 3, 1968; New York, N.Y., January 31, 1969; Fort Lauderdale, Fla., December 1, 1969; Los Angeles, Calif., November 30, 1970; Phoenix, Ariz., November 29, 1971; St. Petersburg, Fla., March 23, 1972; Honolulu, Hawaii, November 27, 1972; Houston, Tex., December 3 and 7, 1973; New Orleans, La., December 2, 1974; Hollywood, Fla., December 8, 1975; Los Angeles, Calif., December 6, 1976; Honolulu, Hawaii, December 5, 1977; Orlando, Fla., December 4, 1978; Toronto, Ontario, Canada, December 3, 1979; Dallas, Tex., December 8, 1980; Hollywood, Fla., -

S COMMITTEE: 02-01-12 Item: F CITY of ~ Memorandum S Josq Caprlal Ot SILICON VALLEY

RULES COMMITTEE: 02-01-12 Item: F CITY OF ~ Memorandum s josq CAPrlAL Ot SILICON VALLEY TO: Honorable Mayor & FROM: Dennis Hawldns, CMC City Council City Cleric SUBJECT: The Public Record DATE: January 27, 2012 January 20 - 26, 2012 ITEMS TRANSMITTED TO THE ADMINISTRATION ITEMS FILED FOR THE PUBLIC RECORD (a) Notification letter to Mayor Reed and the City Council from Verizon Wireless dated December 27, 2011 regarding San Jose State University, GTE Mobilnet of California Limited Partnership (U-3002-C), of San Jose, CA MSA. (b) Letter to Mayor Reed and the City Council from Martha O’Connell dated January 22, 2012 regarding Agenda Template for Boards and Commissions - Open Forum Placement. (c) Letter to Mayor Reed and City Council from Martha O’Connell dated January 26, 2012 regarding Raising the Sales Tax While Failing to Cut the Costs of Boards and Colnmissions. (d) Letter to Mayor Reed and the City Council from David Wall dated JanumT 26, 2012 regarding "Request #2 for an investigation into the $400,000 lost by the Office of the City Manager." (e) Letter to Mayor Reed and.the City Council from David Wall dated January 26, 2012 regarding "(Week #4): City Manager has yet to publicly ’Thank’ City Attorney for ’bailout’ on EIC!" (f) Letter to The Office of the Commissioner of Baseball from David Wall dated January 26, 2012 regarding ’Bribery at elections." /’) ~/~l?~21~wkins’ CMC DH!tld Distribution: Mayor/Council Director of Transportation City Manager Public Information Officer Assistant City Manager San Josd Mercury News Assistant to City Manager Library Council Liaison Director of Public Workg Director of Planning City Auditor City Attorney Director of Finance PUBLIC RECORDS. -

6.07 BATTING out of TURN (A) a Batter Shall Be Called Out, on Appeal

6.07 BATTING OUT OF TURN (a) A batter shall be called out, on appeal, when he fails to bat in his proper turn, and another batter completes a time at bat in his place. (1) The proper batter may take his place in the batter's box at any time before the improper batter becomes a runner or is put out, and any balls and strikes shall be counted in the proper batter's time at bat. (b) When an improper batter becomes a runner or is put out, and the defensive team appeals to the umpire before the first pitch to the next batter of either team, or before any play or attempted play, the umpire shall (1) declare the proper batter out; and (2) nullify any advance or score made because of a ball batted by the improper batter or because of the improper batter's advance to first base on a hit, an error, a base on balls, a hit batter or otherwise. NOTE: If a runner advances, while the improper batter is at bat, on a stolen base, balk, wild pitch or passed ball, such advance is legal. (c) When an improper batter becomes a runner or is put out, and a pitch is made to the next batter of either team before an appeal is made, the improper batter thereby becomes the proper batter, and the results of his time at bat become legal. (d) (1) When the proper batter is called out because he has failed to bat in turn, the next batter shall be the batter whose name follows that of the proper batter thus called out; (2) When an improper batter becomes a proper batter because no appeal is made before the next pitch, the next batter shall be the batter whose name follows that of such legalized improper batter. -

June-12-2020-CB-Digi

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 63, No. 11 Friday, June 12, 2020 $4.00 50 Amazing ’Series Memories Drama, wild moments highlight the history of the College World Series for the past 73 years. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball MAHA, Neb. — Since there is no College World Series this Oyear because of the coronavirus pandemic, Collegiate Baseball thought it would be a good idea to remind people what a remarkable event this tournament is. So we present the 50 greatest memories He had not hit a home run all season in CWS history. long. 1. Most Dramatic Moment To End With one runner on, he hit the only Game: With two outs in the bottom of the walk-off homer to win a College World ninth in the 1996 College World Series Series in history as it barely cleared the championship game, Miami (Fla.) was on right field wall as LSU pulled off a 9-8 the cusp of winning the national title over win in the national title game. Louisiana St. with 1-run lead. 2. Greatest Championship Game: With one runner on, LSU’s Warren Southern California and Florida State Morris stepped to the plate. played the greatest College World Series He did not play for 39 games due to a championship game in history. WILD CELEBRATIONS — The College World Series in Omaha has featured fractured hamate bone in his right wrist The Trojans beat the Seminoles, 2-1 remarkable moments over the past 73 years, including plenty of dog piles to and only came back to the starting lineup celebrate national championships. -

The Retro Sheet Retro News 9 Official Publication of Retrosheet, Inc

June 2, 1999 Inside: Volume 6, Number 2 Game Acquisitions 2 Nominations Sought 3 Strange Plays 5 The Retro Sheet Retro News 9 Official Publication of Retrosheet, Inc. There are two topics for this column: game logs and data release policy. The game log story is really just an up- date from last time. Since then Tom Ruane has done a lot of work getting the logs organized. He has had help from Mark Armour who is filling in some of the gaps, especially umpires. In addition David Vincent has written a program that will make access to these logs easy and logical. All that is left is to get the logs posted on the web site, which we hope will be accomplished very soon, perhaps even before you read this notice. The Retrosheet Board of Directors explicitly gave permission to the President of the organiza- tion to decide when a given data file was ready to release. Up to this point, I have been very conservative and we have only released files that had undergone exhaustive proofing. For ex- ample, totals generated from our play by play files agree to the greatest extent possible with the official totals in all batting and pitching categories. For those cases (very few) where our numbers differ from the official totals, we have detailed descriptions of the source of these dif- ferences. The logic behind this slow approach is that I thought it would be damaging to our credibility to release one ver- sion of a file without detailed proofing and then to replace it later after we had made corrections. -

Little League Baseball Rules Quiz

LITTLE LEAGUE BASEBALL RULES QUIZ How well do you know Little League baseball rules? Answer True or False to each of the following statements: 1 The ball is dead on a foul tip. 2 A batted ball that hits the plate is a foul ball. 3 The base coach can’t leave the coach’s box during play or he/she will be guilty of interference. 4 A batter-runner cannot overrun first base on a base-on-balls. 5 A fly ball that is deflected over the fence in fair territory is a ground rule double. 6 A base runner cannot be guilty of interference on a ground ball if he/she doesn’t touch the fielder. 7 A batter who bats of order is out. 8 The pitcher always gets eight warm-up pitches between innings. 9 If a pitch hits a batter’s hands it’s considered a foul ball, since the hands are considered part of the bat. 10 When the catcher blocks the plate without the ball, it should be called interference. 11 On close plays into home, the base runner must slide or he/she will be called out. 12 A batter hitting the ball twice is OK, if it’s not intentional. 13 In order to be called out on a foul ball, the batted ball must go higher than the batter’s head. 14 If a fielder holds a fly ball for two seconds it's a legal catch, even if he/she drops it thereafter. 15 A runner who runs more the three feet away from a direct line between bases is out of the baseline and should be called out. -

Palisades Pony Baseball Association Ppba Policy

PALISADES PONY BASEBALL ASSOCIATION PPBA POLICY MANUAL A COMMUNITY ENTERPRISE SUPPORTED BY: COMMUNITY SPONSORS PARENTS VOLUNTEERS DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS UNDER LEADERSHIP OF: VOLUNTEERS AND STAFF LOS ANGELES CITY DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND PARKS PACIFIC PALISADES RECREATION CENTER LEAGUE TELEPHONE: (310) 459-0192 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PURPOSES ...................................1 II. PLAYER'S PLEDGE ............................1 III. RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE ADVISORY BOARD . 2 IV. RESPONSIBILITIES OF COACHES, PARENTS AND PLAYERS................................3 V. ELIGIBILITY AND REGISTRATION ..............5 VI. WAITING LIST ................................7 VII. PLAYER DRAFT...............................7 VIII. LEAGUES, ORGANIZATIONS AND TEAMS .......8 IX. SCHEDULES AND POSTPONEMENTS............9 X. PLAYING RULES ..............................9 1. Base Running — Stealing.....................9 2. Pinto Base Running .........................9 3. Base Running — Other Rules ................10 4. Pitching ..................................11 5. Pitching Eligibility & Pitch Count . 14 6. Batting...................................15 7. Substitution & Playing Time .................17 8. Minimum Number of Players .................18 9. Dugout Rule . 19 10. Bucket Rule .............................19 11. Time-Out Rule ...........................20 XI. DISPUTES . 20 XII. INNINGS, TIME LIMITS AND TIES .............20 1. Innings...................................20 (including Complete Game, Suspended Game, etc.,) 2. Times....................................22 -

Coaching Baseball for Dummies‰

01_089606 ffirs.qxp 2/21/07 7:00 PM Page iii Coaching Baseball FOR DUMmIES‰ by National Alliance For Youth Sports with Greg Bach 01_089606 ffirs.qxp 2/21/07 7:00 PM Page ii 01_089606 ffirs.qxp 2/21/07 7:00 PM Page i Coaching Baseball FOR DUMmIES‰ 01_089606 ffirs.qxp 2/21/07 7:00 PM Page ii 01_089606 ffirs.qxp 2/21/07 7:00 PM Page iii Coaching Baseball FOR DUMmIES‰ by National Alliance For Youth Sports with Greg Bach 01_089606 ffirs.qxp 2/21/07 7:00 PM Page iv Coaching Baseball For Dummies® Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2007 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317-572-3447, fax 317-572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.