Knights of Columbus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHEN a KNIGHT ACTS Selflessly, He Acts on Behalf of the World. SURGE

962 3-13 8-47 cover_962 4/10/13 3:06 PM Page 1 WHEN A KNIGHT ACTS selflessly, he acts on behalf of the world. SURGE . .WITH SERVICE m 962 3-13 8-47 cover_962 4/10/13 3:06 PM Page 2 Knights of Columbus A Catholic, Family, Fraternal, Service Organization THE SERVICE PROGRAM: • Provides opportunity for direct involvement; • Stimulates personal commitment; • Creates more family participation; • Strengthens and spreads fraternalism; • Provides service to Church, community, council, family, culture of life and youth; • Establishes the council as an influential and important force; • Elevates the status of programming personnel; • Develops more meaningful and relevant programs of action; • Establishes direct areas of responsibility; • Builds leadership; • Ensures success of council’s programs; and • Provides recruitment opportunities. Check out our Web site at: www.kofc.org 962 3-13 8-47 inside_962 4/10/13 3:05 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Implementing the Service Program ............................................ 2 Direct Involvement and Personal Commitment ....................... 5 Church Activities .......................................................................... 8 Community Activities ................................................................. 13 Council Activities ........................................................................ 19 Family Activities ......................................................................... 23 Culture of Life Activities............................................................... 27 -

A Closer Look at Argus Books' 1930 the Lives of the Twelve Caesars

In the Spirit of Suetonius: A Closer Look at Argus Books’ 1930 The Lives of the Twelve Caesars Gretchen Elise Wright Trinity College of Arts and Sciences Duke University 13 April 2020 An honors thesis submitted to the Duke Classical Studies Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction for a Bachelor of Arts in Classical Civilizations. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Chapter I. The Publisher and the Book 7 Chapter II. The Translator and Her “Translation” 24 Chapter III. “Mr. Papé’s Masterpiece” 40 Conclusion 60 Illustrations 64 Works Cited 72 Other Consulted Works 76 Wright 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, this project would never have existed without the vision and brilliance of Professor Boatwright. I would like to say thank you for her unwavering encouragement, advice, answers, and laughter, and for always making me consider: What would Agrippina do? A thousand more thanks to all the other teachers from whom I have had the honor and joy of learning, at Duke and beyond. I am so grateful for your wisdom and kindness over the years and feel lucky to graduate having been taught by all of you. My research would have been incomplete without the assistance of the special collections libraries and librarians I turned to in the past year. Thank you to the librarians at the Beinecke and Vatican Film Libraries, and of course, to everyone in the Duke Libraries. I could not have done this without you! I should note that I am writing these final pages not in Perkins Library or my campus dormitory, but in self-isolation in my childhood bedroom. -

Bulletincoverpage 2021.Pub

St. Joseph Catholic Church 1294 Makawao Avenue, Makawao, HI 96768 SCHEDULE OF SERVICES CONTACT INFORMATION DAILY MASS: Monday-Friday…...7 a.m. Office: (808) 572-7652 Saturday Sunday Vigil 5:00 p.m. Fax: (808) 573-2278 Sunday Masses: 7:00 a.m., 9:00 a.m. & 5:00 p.m. Website: www.sjcmaui.org Confessions: By appointment only on Tuesday, Thurs- Email: day, & Saturday from 9a.m. - 11 a.m. at the rectory. Call [email protected] 572-7652 to schedule your appointment. PARISH MISSION: St. Joseph Church Parish is a faith community in Makawao, Maui. We are dedicated to the call of God, to support the Diocese of Honolulu in its mission, to celebrate the Eucharist, and to commit and make Jesus present in our lives. ST. JOSEPH CHURCH STAFF Administrator: Rev. Michael Tolentino Deacon Patrick Constantino Business Administrator: Donna Pico EARLY LEARNING CENTER Director: Helen Souza; 572-6235 Office Clerk: Sheri Harris Teachers: Renette Koa, Cassandra Comer CHURCH COMMITTEES Pastoral Council: Christine AhPuck; 463-1585 Finance Committee: Ernest Rezents; 572-8663 Church Building/Master Planning: Jordan Santos; 572-9768 Stewardship Committee: Arsinia Anderson; 572-8290 & Helen Souza; 572-5142 CHURCH FUNDRAISING Thrift Shop: Joslyn Minobe: 572-7652 Sweetbread: Jackie Souza: 573-8927 St. Joseph Feast: Donna Pico: 572-7652 CHURCH MINISTRIES WORSHIP MINISTRY Altar Servers: Helen Souza: 572-5142 Arts & Environment: Berna Gentry: 385-3442 Lectors: Erica Gorman; 280-9687 Extraordinary Minister of Holy Communion/Sick & Homebound: Jamie Balthazar; 572-6403 -

The Central Symbol Is a Cross, Triparted and Fre Ered. This Signifies The

Issue 1—December 2019 Brother Knights I am delighted to welcome you to the first edition of "The Alliance" the bi-monthly e-newsletter of the International Alliance of Catholic Knights. At the recent conference in Glasgow the Supreme Knights and their representatives from around the world decided that it was important that Knights across the world could share their thoughts, ideas and vision to fulfil the original ideas of Fr McGilvney. That all our Orders shared the same unity of purpose all over the world and it was important that each of us were aware of the actions of our brothers in different countries and indeed continents given that, sadly we now live in a world where attacks on our Christian and Catholic faith, both physical and otherwise, have become the norm and more worryingly accepted without question. The central symbol is a Where belief in the faith of our Lord Jesus Christ in the West is ridiculed and cross, triparted and denigrated and in other parts of the world where being a Christian puts your very life freered. This signifies the at risk. Orders of Catholic Knights A world were attacks on family life, attacks on the unborn and undervaluing the right coming together in their to live a full life from conception to a natural death is part of mainstream politics. And a world where Catholic and Christian principles in general, no longer apply. common allegiance to the That is why the mission of our Orders of Knights throughout the world are so relevant faith and so important today. -

Public Safety Personnel Need to This Means That an Applicant Or Member Accepts the Join the Knights of Columbus

Did You Know? Statistics One asset of the Order’s fraternal benefits program • There is no more highly rated insurer is its ability to reach out to the needs of the world. in North America than the Knights Knights proudly support: of Columbus.* A Guide to the • Charities of the Holy Father • Culture of Life Programs • More than $8 billion of insurance issued Benefits of Membership • Special Olympics annually in the Knights of Columbus • Catholic Education Programs • Numerous Youth Programs • Over $105 billion total insurance in force for • Religious Vocations • Over 2 million certificates in force Public Safety In the wake of the tragic events of September 11th, 2001, the Knights • Over $22 billion in assets Personnel were among the first to respond by • Over 1.9 million members Orderwide establishing the $1 Million Heroes Fund. This fund gave immediate • Over $1.5 billion donated to charity financial assistance to the families in the last decade of those emergency personnel that lost their lives in the attacks. • Over 700 million volunteer hours in the last decade The Insurance Program *As of 1/1/2017, rated A++ (Superior) for financial strength by A.M. Best. The Knights of Columbus offers a variety of Insurance For information on joining the Order or products to members and their families. Whole Life the many fraternal benefits and programs and Term Insurance is available, as well as disability income insurance, long-term care insurance and we offer, please contact: retirement annuities at very competitive interest rates. If our whole life insurance and term programs are not exactly what you are looking for, we offer a Discoverer Plan — a combination of whole and term life insurance. -

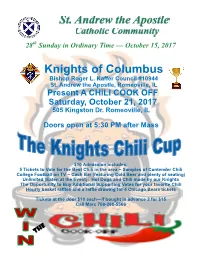

Knights of Columbus Bishop Roger L

28th Sunday in Ordinary Time — October 15, 2017 Knights of Columbus Bishop Roger L. Kaffer Council #10944 St. Andrew the Apostle, Romeoville, IL Present A CHILI COOK OFF Saturday, October 21, 2017 505 Kingston Dr. Romeoville, IL Doors open at 5:30 PM after Mass $10 Admission includes: 5 Tickets to Vote for the Best Chili in the area ~ Samples of Contender Chili College Football on TV ~ Cash Bar (featuring Cold Beer and plenty of seating) Unlimited (Eaten at the Event): Hot Dogs and Chili made by our Knights The Opportunity to Buy Additional Supporting Votes for your favorite Chili Hourly basket raffles and a raffle drawing for 4 Chicago Bears tickets Tickets at the door $10 each—if bought in advance 2 for $15 Call Marc 708-268-5566 Page Two October 15, 2017 Mass Intentions This Week E=English P=Polish S=Spanish Ch=Church Monday, October 16 Drama Club 2:30 pn —6:00 pm Parish Hall Saturday, October 14 Prayer Vigil Charismatic 6:30 pm—9:30 pm St. Mary Back Room 204 8:00 AM —Martin Hozjan by Marian Incavo 4:00 PM — Frank and Josephine Kamradt by FrankKamradt Legion of Mary 7:00 pm—9:00 pm Conf. Room A 5:30 PM — John Ray by Elizabeth Ray Tuesday, October 17 Sunday, October 15 Drama Club 2:30 pn —6:00 pm Parish Hall 7:30 AM—(E-Ch) Margaret Homerding by Robert and Rosalie Parish Council 7:00 pm—9:00 pm Parish Office Braasch Rosary 7:00 pm — 7:30 pm St. -

St. Paul the Apostle and Immaculate Conception Churches BARRISTERS & SOLICITORS Bread Est

Liturgical Publications 3171 LENWORTH DR. #12 MISSISSAUGA, ON L4X 2G6 (800) 268-2637 FEEHELY, GASTALDI Barber Rose's SHELBURNE MEMORIALS Ltd. St. Paul the Apostle and Immaculate Conception Churches BARRISTERS & SOLICITORS Plus Bread Est. 1888 5 Mill St. E., Tottenham Owned & Operated by 23 Young St. Basket (905) 936-4262 (Young/King Plaza) The European Bakery Café 2 Victoria St. E., Alliston Bob & Linda McBride 126 Victoria St. W. 705.434.4928 34 Victoria St. E. 705-434-2108 (705) 435-4386 Monuments for All Cemeteries 705.250.1994 W. John Thomas ALLISTON All work completed at DENTAL same location Funeral Home www.shelburnememorials.com GROUP FAMILY OWNED SINCE 1958 Personal & Professional Service Your Family Dentist 519-925-3036 • Craftsmanship Integrity & Trust 1-800-668-8756 27 Victoria Street East • Comfort (widths) 709 Industrial Rd., Shelburne 705-435-5101 705-435-5022 • Attention to detail Geof Tan Contracting NNY LARRY'S established 1946 JOH & HANDYMAN SERVICES • Basement Finishing ROGER'S Savings • GIC's •Loans Construction Repairs, Plumbing, • Home Improvements Graced by the constant, loving presence of God - Father, Son and Holy Spirit - in our lives, energized by the Mortgages • Lines of Credit Tiles, Concrete, Drywall, etc. intercession of Mary and the great Communion of Saints, and grounded in the Sacred Scripture, Tradition, • Handyman Services PIZZA ~ No Job Too Small ~ 85 VICTORIA ST. W. 7320 St. James Lane, Colgan 312 Victoria St. E. Alliston 705-435-6481 Catholic Teaching, Sacrament and Prayer, we, parishioners of St. Paul the Apostle Parish, reach out to (905) 936-2761 embrace all of God's children, encouraging them to receive the gift of eternal salvation, accept Jesus Christ as 705-435-9046 705•434•9696 226-200-0202 www.herbertsboots.com their Lord, and follow in his footsteps. -

KOCO-132872298 State Tracking #: KOCO-132872298 Company Tracking

SERFF Tracking #: KOCO-132872298 State Tracking #: KOCO-132872298 Company Tracking #: State: Virginia Filing Company: Knights of Columbus TOI/Sub-TOI: LTC Annual Rate Report/LTCINLM Product Name: LTC Annual Rate Report (LTCINLM) - CY2020 Project Name/Number: LTC Annual Rate Report (LTCINLM) - CY2020/ Filing at a Glance Company: Knights of Columbus Product Name: LTC Annual Rate Report (LTCINLM) - CY2020 State: Virginia TOI: LTC Annual Rate Report Sub-TOI: LTCINLM Filing Type: LTC Annual Rate Report Date Submitted: 06/12/2021 SERFF Tr Num: KOCO-132872298 SERFF Status: Closed-Filed State Tr Num: KOCO-132872298 State Status: Filed Co Tr Num: Effective 06/30/2021 Date Requested: Author(s): Barbara Caruso Reviewer(s): Bill Dismore (primary) Disposition Date: 06/23/2021 Disposition Status: Filed Effective Date: PDF Pipeline for SERFF Tracking Number KOCO-132872298 Generated 06/25/2021 12:23 AM SERFF Tracking #: KOCO-132872298 State Tracking #: KOCO-132872298 Company Tracking #: State: Virginia Filing Company: Knights of Columbus TOI/Sub-TOI: LTC Annual Rate Report/LTCINLM Product Name: LTC Annual Rate Report (LTCINLM) - CY2020 Project Name/Number: LTC Annual Rate Report (LTCINLM) - CY2020/ General Information Project Name: LTC Annual Rate Report (LTCINLM) - CY2020 Status of Filing in Domicile: Not Filed Project Number: Date Approved in Domicile: Requested Filing Mode: Informational Domicile Status Comments: Connecticut, our state of domicile, does not require. Explanation for Combination/Other: Market Type: Individual Submission Type: New Submission Individual Market Type: Overall Rate Impact: Filing Status Changed: 06/23/2021 State Status Changed: 06/23/2021 Deemer Date: Created By: Barbara Caruso Submitted By: Barbara Caruso Corresponding Filing Tracking Number: State TOI: LTC Annual Rate Report 2021 Filing Description: The Knights of Columbus (NAIC #58033) is submitting its LTC Annual Rate Report for calendar year 2020 for policies issued on or after October 1, 2003 that are no longer marketed (LTCINLM). -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

WHEN a KNIGHT ACTS Selflessly, He Acts on Behalf of the World

915 3-13 8-47 cov_915 Cover 4/3/13 2:38 PM Page 1 WHEN A KNIGHT ACTS selflessly, he acts on behalf of the world. GRAND KNIGHT’S HANDBOOK m KNIGHTS ® OF COLUMBUS In service to One. In service to all. 915 3-13 8-47 cov_915 Cover 4/3/13 2:38 PM Page 2 915 3-13 8-47 inside_915 INSIDE 4/3/13 2:33 PM Page 1 GRAND KNIGHT’S HANDBOOK KNIGHTS OF COLUMBUS SUPREME COUNCIL OFFICE 1 COLUMBUS PLAZA NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT 06510-3326 www.kofc.org 915 3-13 8-47 inside_915 INSIDE 4/3/13 2:33 PM Page 2 2 COUNCIL OFFICERS’ CHECKLIST DUE DATE FORM/REPORT/ACTION July 1 Council Per Capita ($1.75) and Catholic Advertising ($.50) Assessments Levied by Supreme Council based on total membership minus honorary, honorary life members and disability members) July 1 Culture of Life fund assessment levied by Supreme Council based on total membership minus honorary life, disability and inactive insurance members. July 1 Report of Council Officers. (#185) August 1 Service Program Personnel Report. (#365) August 15 Semiannual Audit Report. (#1295) As of June 30th September 1 Columbian Squires Officers and Counsellors Report (#468) September 1 Notice of Appointment of Round Table Coordinator (#2629) October 10 Suspension of Council if July Assessments are not paid. January 1 Council Per Capita ($1.75) and Catholic Advertising ($.50) Assessments Levied by Supreme Council based on total membership minus honorary, honorary life members and disability members) January 1 Culture of Life fund assessment levied by Supreme Council based on total membership minus honorary life, disability and inactive insurance members. -

Volume 16: 1945-46

DePaul University Via Sapientiae De Andrein Vincentian Journals and Publications 1946 Volume 16: 1945-46 Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Volume 16: 1945-46. https://via.library.depaul.edu/andrein/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in De Andrein by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IC It iZtAnrtiu Volume 16 Perryville, Missouri, October, 1945 Number 1 St. Vincent de Paul Society in America Has Vincentian Origin In observance of the Centennial of the St. Vincent De Paul Society in the "AVE ATQUE VALE" United States the Rev. Daniel T. Mc- Colgan of the Boston Archdiocesan Seminary has been designated to write a commemorative history. Directed to Father Bayard for help regarding Father Timon's rumored connection with the introduction of the organiza- tion into this country, the Boston writ- er contacted our Community historian. We have seen the carbon copy of Father Bayard's reply and here quote a significant portion' of its enlighten- ing contents: "Father Timon visited Europe in the summer of 1845 and actively interest- ed himself in the establishment of the St. Vincent de Paul Society in America. Apparently he had appraised the work of the organization on one or more of his previous visits (1837, 1841, and 1843) and had talked up its excellence in St. -

A History of Divine Word Missionaries in Ghana: 1938-2010

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh A HISTORY OF DIVINE WORD MISSIONARIES IN GHANA: 1938-2010 BY JOSEPH KWASI ADDAI (10328424) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF M.PHIL RELIGIONS DEGREE JUNE, 2012 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION This thesis, with the exception of materials quoted from other scholarly works which have been acknowledged fully, is the original production of research work by the researcher under the supervision of Rev. Prof. Cephas N. Omenyo and Rev. Fr. Dr. George Ossom- Batsa at the Department for the Study of Religions, University of Ghana. Any error in this thesis is fully acknowledged as the fault of the researcher. Signature: ………………………………. Date: …………………… Joseph Kwasi Addai (Student) Signature: ………………………………. Date: …………………… Rev. Prof. Rev. Prof. Cephas N. Omenyo (Supervisor) Signature: ………………………………. Date: …………………… Rev. Fr. Dr. George Ossom-Batsa (Supervisor) i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT The problem of this study was that, although the SVD missionaries have been a major partner in the evangelizing mission of the Roman Catholic Church in Ghana since their arrival in 1938, their specific contribution to the growth and development of the Catholic Church in Ghana has not been fully assessed. The objective of this thesis therefore is to appraise the missionary activities of the SVD within Ghanaian Catholic Church, and also assess their relevance in contemporary Ghanaian Christianity as a whole. Using the historical method and approach, chapter two traces the history of the SVD from the time of the arrival of the first two missionaries up to the time the mission was handed over to a diocesan bishop in 1971.