Mae-Guatemala-Final-Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Tropical Timber Organization

INTERNATIONAL TROPICAL TIMBER ORGANIZATION ITTO PROJECT PROPOSAL TITLE: INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND BIODIVERSITY IN THE TACANÁ VOLCANO AND ITS RANGE OF INFLUENCE IN MEXICO AND GUATEMALA SERIAL NUMBER: PD 668/12 Rev.1 (F) COMMITTEE: REFORESTATION AND FOREST MANAGEMENT SUBMITTED BY: GOVERNMENT OF GUATEMALA ORIGINAL LANGUAGE: SPANISH SUMMARY Guatemala and Mexico share the Tacaná Volcano border area which straddles the Department of San Marcos and the State of Chiapas respectively, an area in the Mesoamerican Biodiversity Corridor, featuring biological richness and ecotourism potential although most of the population lives in poverty, using natural resources unsustainably. An initiative was developed for sustainable development in the protected areas of the Tacaná Volcano border area, based on coordinated actions, a study of the situation and various exchanges between regional representatives of Mexican and Guatemalan Government institutions, civil society and the Swiss organization HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation that has a long history of work in Latin America. The objective of the project is to contribute to improving living standards for 28,000 people in both countries, based on the conservation and sustainable use of local natural resources. The project begins with an initial two- year phase to establish the foundations of joint work with the community, both men and women, with pilot activities including forest management, diversification of economic opportunities, upgrade of the legal framework of Protected Areas and enhancement of collaboration between both countries. The initiative has the backing of ITTO focal points in Guatemala (INAB and CONAP), and in Mexico (CONAFOR and CONANP). EXECUTING AGENCY HELVETAS SWISS INTERCOOPERATION (HSI) COLLABORATING AGENCIES DURATION 24 MONTHS APPROXIMATE STARTING DATE UPON APPROVAL BUDGET AND PROPOSED Source Contribution SOURCES OF FINANCE: in US$ ITTO 641,638.80 HSI 67,696.80 Municipalities (approx. -

Juan Skinner Alvarado, Msc Member of the Scientific Committee AGENDA

Integrated Lake Basin Management (ILBM): obstacles and opportunities for wastewater management in the lake Atitlán basin Juan Skinner Alvarado, MSc Member of the Scientific Committee AGENDA: 1. Integrated Lake Basin Management - ILBM 2. Background of wastewater management infrastructure development in the lake Atitlán basin – lessons learned 3. Obstacles in wastewater management at the lake Atitlán Basin 4. Opportunities in wastewater management for lake Atitlán. 1. Integrated Lake Basin Management ILBM Manejo Integrado de Cuencas de Lagos LBMILBMI– Lake Basin Management Initiative Una revisión global sobre el manejo de cuencas de lagos Analiza e identifica las lecciones aprendidas de la experiencia de manejo de 28 lagos del mundo. Análisis de las amenazas A definition of Integrated Lake Basin Management (ILBM) is coined with the LBMI Integrated Lake Basin Management (ILBM) is an approach to achieve the sustainable management of lakes and reservoirs through gradual, continuous and comprehensive improvements in the governance of the basin, including efforts to integrate institutional responsibilities, public policies, participation of interest groups, scientific and traditional knowledge, technological options, and financing prospects and their restrictions. La gobernanza es una noción que busca -antes que imponer un modelo- describir una transformación sistémica compleja, que se produce a distintos niveles -de lo local a lo mundial- y en distintos sectores -público, privado y civil-.(Fuente: wikipedia) The 6 lake basin governance pillars Un marco teórico para el análisis y planificación de la gestión de lagos ILEC Scicom More Sustainable 3. Seek ways to strengthen the governance pillars 2. Identify issues, needs and challenges Monitoring, Reconnaissance Survey, Inventory and Databases LevelofSustainability 1. -

Mining Conflicts and Indigenous Peoples in Guatemala

Mining Conflicts and Indigenous Peoples in Guatemala 1 Introduction I Mining Conflicts and Indigenous Indigenous and Conflicts Mining in Guatemala Peoples Author: Joris van de Sandt September 2009 This report has been commissioned by the Amsterdam University Law Faculty and financed by Cordaid, The Hague. Academic supervision by Prof. André J. Hoekema ([email protected]) Guatemala Country Report prepared for the study: Environmental degradation, natural resources and violent conflict in indigenous habitats in Kalimantan-Indonesia, Bayaka-Central African Republic and San Marcos-Guatemala Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to all those who gave me the possibility to complete this study. Most of all, I am indebted to the people and communities of the Altiplano Occidental, especially those of Sipacapa and San Miguel Ixtahuacán, for their courtesy and trusting me with their experiences. In particular I should mention: Manuel Ambrocio; Francisco Bámaca; Margarita Bamaca; Crisanta Fernández; Rubén Feliciano; Andrés García (Alcaldía Indígena de Totonicapán); Padre Erik Gruloos; Ciriaco Juárez; Javier de León; Aníbal López; Aniceto López; Rolando López; Santiago López; Susana López; Gustavo Mérida; Isabel Mérida; Lázaro Pérez; Marcos Pérez; Antonio Tema; Delfino Tema; Juan Tema; Mario Tema; and Timoteo Velásquez. Also, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to the team of COPAE and the Pastoral Social of the Diocese of San Marcos for introducing me to the theme and their work. I especially thank: Marco Vinicio López; Roberto Marani; Udiel Miranda; Fausto Valiente; Sander Otten; Johanna van Strien; and Ruth Tánchez, for their help and friendship. I am also thankful to Msg. Álvaro Ramazzini. -

San Marcos La Laguna

CO DIGO : AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS E INUNDACIONES 716 DEPARTAMENTO DE SOLOLÁ 8 MUNICIPIO DE SAN MARCOS LA LAGUNA AMENAZ A PO R DESLIZ AMIENTO S 420000.000000 91°15'W La pre d ic c ió n d e e sta am e naza utiliza la m e tod ología re c onoc id a a Cruzbe h d e Mora-Vahrson, para e stim ar las am e nazas d e d e slizam ie ntos a " ac am P un nive l d e d e talle d e 1 kiló m e tro. Esta c om ple ja m od e lac ió n utiliza ío R una c om binac ió n d e d atos sobre la litología, la hum e d ad d e l sue lo, "Pamezabal Chuimacha " pe nd ie nte y pronó stic os d e tie m po e n e ste c aso pre c ipitac ió n Chichimuch " ac um ulad a q ue CATHALAC ge ne ra d iariam e nte a través d e l m od e lo m e sosc ale PSU/NCAR, e l MM5. Se e stim a e sta am e naza e n térm inos d e ‘Baja’, ‘Me d ia’ y ‘Alta‘. "Nicajilin Alta A Z A N E M A SANTA E ^ LUCIA D Santa L Media UTATLAN Lucia E V Cerro I ^ N "Utatlan "La Paz Chuichimuch " Baja ra scale hui o C Rí AMENAZ A "Chuicruz PO R INUNDACIO NES La pre d ic c ió n d e e sta am e naza utiliza la m e tod ología d e Te rraVie w Chuichimuch " 4.2.2 y su plugin Te rraHyd ro (S.Rossini). -

Informe De Medio Término Del Examen Periódico Universal EPU

Informe de Medio Término del Examen Periódico Universal EPU Seguimiento a las recomendaciones sobre la situación de violencia contra las mujeres. Departamento de Sololá, Guatemala. Informe elaborado por el Colectivo EPU Sololá, para dar seguimiento a las recomendaciones del Examen Periódico Universal 2017 sobre Violencia contra las mujeres. Contiene datos, análisis y recomendaciones referidas a dichas recomendaciones en 5 municipios de Sololá en los cuales trabajan las organizaciones integrantes del Colectivo: AMLUDI, CPDL Y MPDL. Informe de Medio Término del Examen Periódico Universal EPU Seguimiento a las recomendaciones sobre la situación de violencia contra las mujeres. Departamento de Sololá, Guatemala Presentación Este informe fue elaborado en forma unificada por Datos de la Asociación de Mujeres Luqueñas, AMLUDI; el Sololá: Colectivo Poder y Desarrollo Local, CPDL y la Asociación Movimiento por la Paz, el Desarme y la El Departamento de Libertad, MPDL, organizaciones de sociedad civil Sololá (14°46′26″N que realizan acciones orientadas a la eliminación de 91°11′15″O) cuenta con las violencias contra las mujeres. 437.145 habitantes. (51.46% mujeres), con En el presente informe, los municipios de San Lucas una población Tolimán, San Andrés Semetabaj, San Antonio mayoritariamente Palopó, Nahualá y Santa Lucía Utatlán, del indígena y rural (el 89 % vive en área rural y el departamento de Sololá, fueron los lugares en los cuales se verificó la forma en que se han 94% pertenece a tres pueblos mayas: implementado las Recomendaciones a Guatemala K’aqchiqueles, K’iche’s y para atender la situación de violencia que viven las Tz’utujiles), según el mujeres. -

Wastewater Management in the Basin of Lake Atitlan: a Background Study

WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT IN THE BASIN OF LAKE ATITLAN: A BACKGROUND STUDY LAURA FERRÁNS, SERENA CAUCCI, JORGE CIFUENTES, TAMARA AVELLÁN, CHRISTINA DORNACK, HIROSHAN HETTIARACHCHI WORKING PAPER - No. 6 WORKING PAPER - NO. 6 WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT IN THE BASIN OF LAKE ATITLAN: A BACKGROUND STUDY LAURA FERRÁNS, SERENA CAUCCI, JORGE CIFUENTES, TAMARA AVELLÁN, CHRISTINA DORNACK, HIROSHAN HETTIARACHCHI Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Regional Settings of the Study Area 7 2.1 General Aspects of Guatemala 7 2.2 Location and Population of the Lake Atitlan Basin 8 2.3 Economy of the Region 9 2.4 Hydraulic Characteristics of Lake Atitlan 9 2.5 Water Quality of Lake Atitlan 9 2.5.1 Pollution by Organic and Inorganic Substances 10 2.5.2 Pollution by Pathogens 11 2.6 Impacts on the Region due to Inappropriate Wastewater Management 12 2.6.1 Impacts on Human Health 12 2.6.2 Environmental Impacts on the Lake 13 2.6.3 Economic Impacts 13 3. Wastewater Management in Lake Atitlan 13 3.1 Status of Sanitation Services in the Lake Atitlan Basin 14 3.2 Amount of Wastewater Produced in the Lake Atitlan Basin 15 3.3 Available WWTPs at the Lake Atitlan Basin 16 3.4 Performance of WWTPs Located in the Lake Atitlan Basin 18 3.5 Operation and Maintenance of WWTPs Located in the Lake Atitlan Basin 20 3.5.1 Bottlenecks 20 3.5.2 Potential Solutions 22 4. Major Findings: A Summary 24 Acknowledgment 25 References 26 Wastewater Management in the Basin of Lake Atitlan: A Background Study Laura Ferráns1, Serena Caucci1, Jorge Cifuentes2, Tamara Avellán1, Christina Dornack3, Hiroshan Hettiarachchi1 1 UNU-FLORES, Dresden, Germany 2 Department of Engineering and Nanotechnology of Materials, University of San Carlos of Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala 3 Institute of Waste Management and Circular Economy, TU Dresden, Dresden, Germany ABSTRACT This working paper presents a study on the current wastewater management situation in the basin of Lake Atitlan, Guatemala. -

Republic of Guatemala Guatemala Is a Nation Rich in Almost Four Thousand Years of History

1 Dear Traveler, Our specific goals when we started Explore Guatemala in 2001 were: to share our love of exploring new places to make every aspect of our workshops/tours a “wow” to send travelers home itching to travel with us again It has been very rewarding to see our travel experience goals validated by our customers through their repeat business and workshop/tour evaluations! We personally love our chosen destinations. Currently with Ecuador and Guatemala, most of our venues are listed in the book, 1000 Places to See Before You Die, by Patricia Schultz. We have known these places well for many years and are eager to share them with you. We have selected routes, hotels, dining, and venues reflecting the uniqueness of each area we visit. Our hope is that you will return home with a lasting impression and rewarding memories of the colorful Maya and Inca cultures. ABOUT US All members of the Explore team understand local customs and business practices. We stay in the hotels, eat in the restaurants, and ride the transportation, personally experiencing every aspect of our travel workshops and tours. We know the “hidden treasures” as well as the little bits of information only the locals know. Our experience, relationships, and knowledge of the country allow us to provide a worry-free, life enriching travel adventure, providing a deeper understanding of the way of life, the cultures, nature and societies; in short, we will show you the real Guatemala and Ecuador in a way very few travelers experience. 2 Explore’s Original Company Founders Anita Rogers (Korte) who speaks fluent Spanish, lived in Guatemala for 25 years, started her own business there, and was a collector of Maya weavings as well as Spanish Colonial art and antiques. -

Plan De Desarrollo Municipal Nahualá

PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL NAHUALÁ 0 NAHUALÁ PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL CON ENFOQUE TERRITORIAL 2017-2032 DIRECTORIO Autoridades Municipales: Manuel Tzep Rosario Alcalde Municipal Francisco López Carrillo Concejal Primero Suplente Diego Ricardo Tambriz López Concejal Primero Cristóbal Tzep Ixtós Concejal Segundo Suplente Miguel Balux Guachiac Concejal Segundo Santo Chox Tziquín Concejal Tercero Suplente Manuel Sohom Guarchaj Concejal Tercero Nicolas Mas Sac Síndico Primero Manuel Gregorio Chovón Ixmatá Concejal Quinto Cruz Apolonio Ixquiactap Tzoc Síndico Segundo Edison Nery Jaminez Coj Concejal Sexto Manuel Coj Tambriz Juan Tambriz López Síndico Suplente Concejal Séptimo Con el apoyo técnico metodológico de: Eduardo Secaira Juárez (Asociación Vivamos Mejor) Luis Iván Girón Melgar (Asociación Vivamos Mejor) José Ruiz (Asociación Vivamos Mejor) Santos Álvarez (Asociación Vivamos Mejor) Milton Gutiérrez Rodas (Analista en Planificación Territorial, SEGEPLAN Revisión: Keny Alexander Juárez Santiago (Técnico del Proyecto PPRCC) Johnny Toledo (Revisor, Coordinador del Proyecto PPRCC) La elaboración y reproducción de este documento es posible gracias al apoyo del Proyecto “Paisajes Productivos Resilientes al Cambio Climático y Redes Socioeconómicas Fortalecidas en Guatemala” (PPRCC) que dispone de una donación del Fondo de Adaptación que ejecuta el Ministerio de Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (MARN) e implementa conjuntamente el Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD). 1 NAHUALÁ PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL CON ENFOQUE -

Informe Trimestral De Resultados

Cadenas de Valor Rurales Huehuetenango y San Marcos Rural Value Chains Project USAID Cooperative Agreement 520-A-00004 QUARTERLY REPORT October – December 2013 Guatemala, January 30, 2014 1. Introduction The Rural Value Chains Project (RVCP) falls within the framework for the Feed the Future Initiative (FtF) and is being implemented under a Cooperative Agreement 520-A-12-00004, signed on May 31, 2012 between the National Coffee Association (ANACAFE) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). RVCP implementation is the responsibility of a consortium that includes ANACAFE (as the lead entity with USAID), together with the Guatemalan Confederation of Co-operative Federations, (CONFECOOP in Spanish, represented by the Guatemalan Federation of Agricultural Coffee Producer Co-operatives – FEDECOCAGUA, R.L. in Spanish), the Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives (FEDECOAG, R. L. In Spanish), the Integrated Federation of Handicraft Producer Co-operatives (ARTEXCO, R. L. In Spanish), the Coffee Grower Foundation for Rural Development (FUNCAFE in Spanish) and the FUNDASISTEMAS Foundation. RVCP seeks to accomplish the following objectives: . Reduce poverty and malnutrition rates in 21 municipalities located in the provinces (departamentos in Spanish) of Huehuetenango and San Marcos1 by increasing the household income of small producers that participate in the coffee, horticulture and handicrafts value chains. Promote deep-rooted behavioral changes among the producers and their families to ensure that their increased income is sustainable, but also contributes to improved nutrition over the short, medium and long term. The Consortium member organizations are undertaking activities under each of the components listed below to attain RVCP objectives. I. Improved competitiveness along the value chains; II. -

Diapositiva 1

Con el apoyo del: Resultados del Monitoreo de la situación actual de las acciones de la Ventana de los Mil Días, en los servicios de salud del MSPAS Guatemala octubre , 2017 Ventana de oportunidad de los Mil Días Se le llama así al período que inicia con el embarazo y termina cuando el niño cumple el segundo año de vida. 270 días del embarazo + 365 días del primer año + 365 días del segundo año “Las Acciones de la Ventana de los Mil Días” Son acciones costo/efectivas para acelerar la reducción de la Desnutrición Crónica Infantil ❶ Promoción y apoyo lactancia materna Desnutrición Crónica ENSMI 2014/15 ❷ Alimentación complementaria ❸ Lavado de manos y prácticas de Higiene ❹ Suplementación de Vitamina A ❺ Suplementación de Zinc terapéutico ❻ Micronutrientes en polvo 46.5% ❼ Desparasitación y Vacunación ❽ Suplementación de Hierro y Ácido Fólico 6 de las acciones de la Ventana de ❾ Prevención de la deficiencia de Yodo los Mil Días se evaluaron directamente y para 2 la existencia ❿ Fortificación de Alimentos Básicos de material educativo Monitoreo de la Ventana de los Mil Días Objetivo: Conocer la situación actual en el Marco de la Ventana de los Mil Días, en los servicios de salud del segundo y primer nivel de atención del Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social (agosto 2017). P/S San Martín, Todos Santos Cuchumatán P/S Chiul, Cunen - Quiché Huehuetenango Monitoreo de la Ventana de los Mil Días Cobertura del monitoreo ➢ Se realizó en los servicios de salud de 6 departamentos y 87 municipios. ➢ En total 245 servicios de salud monitoreados. 174 del primer nivel y 71 del segundo nivel. -

References: Acknowledgements

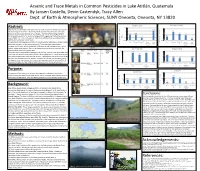

Arsenic and Trace Metals in Common Pesticides in Lake Atitlán, Guatemala By Jansen Costello, Devin Castendyk, Tracy Allen Dept. of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, SUNY Oneonta, Oneonta, NY 13820 Arsenic (As) Manganese (Mn) Abstract: 100 - 10 Lake Atitlán in Guatemala is the main drinking water source for several communities 13.38 3.2 10 µg/L situated along the shoreline. Studies by SUNY Oneonta show that lake water has - 1.5 0.79 0.56 dissolved arsenic concentrations of 11-13 µg/L. The World Health Organization’s 1 1 0.8 drinking water guideline for arsenic is 10 µg/L (REF), suggesting that lake water may 0.5 0.07 per Liter pose a health risk. This study seeks to determine whether local pesticide use may µg/L 0.1 0.21 contribute to observed arsenic levels. 0.01 0.1 The watershed surrounding Lake Atitlán is heavily used for agriculture. Farmers apply Rival Tambo 44 Totem 72 Super Lake Rival Tambo 44 Totem 72 Super Lake Microgram Microgram pesticides to crops in order to increase yields. These pesticides many contain per Liter MIcrogram EC SL Herbaxon Atitlan EC SL Herbaxon Atitlán Figure #7 inorganic constituents which are harmful to humans at high concentrations, such as 20 SL 20 SL Table #1 arsenic, copper, and mercury. Rain rinses these constituents from corps and into Chromium (Cr) Image Pesticide Manufacturer Solution pH Electric Copper (Cu) 9.5 streams, which then flow into the lake. Name Conductivity 10 7.4 10 This experiment measured the composition of the four most common pesticides used (µS/cm) 6.9 Rival Duwest, 50g per 16 L 4.13 1198 µg/L µg/L 4.9 - - 2 in the watershed which we purchased from a farm supply store in Sololá in 2014, plus Honduras 0.7 0.702 two unknown pesticides collected from farmers. -

Pdf | 601.9 Kb

COOPI Cooperazione Internazionale Sismo 7 de Julio 2014 Informe de Situación #2 8 de Julio 2014 22:00 Este cubre el período de 7 de Julio al 8 de Julio. Área de cobertura: Departamento de San Marcos. I. RESUMEN Los mayores de daños son en las viviendas e infraestructura escolar. Aun no hay información completa de la situación. Los daños son muy dispersos y no concentrados, eso dificulta la evaluación de necesidades. La mayoría de familias afectadas se encuentran auto-albergadas con familiares y vecinos, y aun no hay datos sobre el número de auto-albergados. Hay 13 albergues habilitados oficiales en San Marcos pero falta oficializar más albergues. Hay necesidad de apoyo psicosocial para la población afectada y aun no se está atendiendo ese aspecto. Siguen los problemas de acceso vial, de suministro de agua y de suministro de energía eléctrica. II. Visión Generalizada de la Situación El día 7 de julio siendo las 05:24:11 Hrs. se registró un sismo de magnitud 6.4, localizado al Oeste Sur Oeste del departamento de San Marcos. Se reportan daños en los departamentos de San Marcos, Suchitepéquez y Huehuetenango, principalmente en viviendas y daños a personas, personal de SECONRED se dirige al lugar para Evaluación de Daños y Análisis de Necesidades. Fuente: INSIVUMEH Se declaró alerta naranja institucional y poblacional por la CONRED, encabezada por el señor Presidente de la República. El Sr. Gobernador Departamental convocó a los miembros del COE Departamental para su activación, según acta 023-2014 del libro de Gobernación, conjuntamente con el gabinete departamental, desde las 6:30 horas.