Martin Peerson and Greville's Caelica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Madrigal School

THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL SCHOOL Transcribed, Scored and Edited by REV. EDMUND HORACE FELLOWES M.A., Mus.Bac, Oxon. VOL. V. ORLANDO GIBBONS First Set of MADRIGALS AND MOTETS OF FIVE PARTS (Published in 1612) LONDON: STAINER AND BELL, LTD., 58, BERNERS STREET, OXFORD STREET, W. 1914 THE^ENGLISH MADRIGAL SCHOOL. LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS To VOLUMES V.-VIII. Dr. Guido Adler, Proressor of Musical Research in Percy C. Buck, Esq., Mus.Doc, Professor of Music in Vienna University. Trinity College, Dublin ; Director of Music, Harrow W. G. Alcock, Esq., M.V.O., Mus.Doc, Organist and School. Composer to His Majesty's Chapels Royal. F. C. Butcher, Esq., Mus.Bac, Organist and Music B, C. Allchin, Esq., Organist of Hertford College, Master, Hoosac School, New York, U.S.A. Oxford. L. S. R. Byrne, Esq. Hugh P. Allen, Esq., Mus.Doc, Choragus of Oxford University, Organist and Fellow of New College, Capt. Maurice Caillard. Oxford. Sir Vincent H. P. Caillard. The Right Hon. Viscount Alverstone, G.C.M.G., Cardiff University College Library. D.C.L., formerly Lord Chief Justice of England. F. Clive Carey, Esq. (2 copies). E. Amphlett, Esq. Rev. T. B. Carter. W. Anstice, Esq. Sir Francis Champneys, Bart., M.D. Mrs. Argles. The City Glee Club. Godfrey E. P. Arkwright, Esq. J. B. Clark, Esq. Miss Marian Arkwright, Mus. Doc. Rev. Allan Coates. Frl. Amaiie Arnheim. Mrs. Somers V. Cocks. Franck Arnold, Esq. H. C. Colles, Esq., Mus.Bac. Miss R. Baines. The Hon. Mrs. Henn Collins. E. L. Bainton, Esq. Mrs. A. S. Commeline. E. C. -

Redalyc.English Music in the Library of King João IV of Portugal

SEDERI Yearbook ISSN: 1135-7789 [email protected] Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies España Cranmer, David English music in the Library of King João IV of Portugal SEDERI Yearbook, núm. 16, 2006, pp. 153-160 Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies Valladolid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333527602008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative English music in the Library of King João IV 1 of Portugal David CRANMER Universidade Nova de Lisboa ABSTRACT King João IV became King of Portugal in 1640 through the political will of others. His own true passion in life was music. He built up what in his day may well have been the richest music library in Europe. His ambassadors, besides their political duties, were constantly called upon to obtain new musical editions for the library. English music – Catholic sacred music, madrigals, instrumental music – formed a significant part of this collection. This article seeks to describe the extent and comprehensiveness of the English works and to lament the loss of so unparallelled a library in the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. In 1578 the 24-year-old King Sebastião of Portugal led his ill- conceived crusade against the Moors in North Africa. The battle that ensued at Alcazar-Qivir proved to be catastrophic for the Portuguese nation. Not only was the monarch never seen again, but the cream of the Portuguese nobility was killed or taken prisoner. -

The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648). Fang-Lan Lin Hsieh Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1989 The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648). Fang-lan Lin Hsieh Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Hsieh, Fang-lan Lin, "The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648)." (1989). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4722. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4722 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

A Discussion and Modern Edition of Some Works from Walter Porter's Madrigales and Ayres (1632) Linda Dobbs Jones University of Tennessee, Knoxville

University of Tennessee, Knoxville Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-1970 A Discussion and Modern Edition of Some Works from Walter Porter's Madrigales and Ayres (1632) Linda Dobbs Jones University of Tennessee, Knoxville Recommended Citation Jones, Linda Dobbs, "A Discussion and Modern Edition of Some Works from Walter Porter's Madrigales and Ayres (1632). " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1970. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4331 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Trace: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Linda Dobbs Jones entitled "A Discussion and Modern Edition of Some Works from Walter Porter's Madrigales and Ayres (1632)." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Music. Stephen E. Young, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: George F. DeVine Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official student records.) November 15, 1970 To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Linda Dobbs- Jones entitled "A Discussion and Modern Edition of Some Works from Walter Porter's Madrigales and Ayres (1632) ." I recommend that it be accepted for nine quarter hours credit in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Music. -

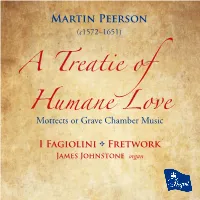

Martin Peerson (C1572–1651)

Martin Peerson (c1572–1651) A Treatie of HMottuectms or aGranve eCh amLber Mouvsic e I Fagiolini E Fretwork James Johnstone organ Martin Peerson (c1572–1651) MotteActs Tor eGartaivee oCfh Hamubmera Mneu sLiqouve e (1630) I Fagiolini E Fretwork James Johnstone organ 1 Love, the delight First part full 3:32 2 Beautie her cover is Second part full 3:04 3 Time faine would stay Third part verse 1:46 4 More than most faire First part full 3:12 5 Thou window of the skie Second part full 2:57 6 You little starres First part verse 1:04 7 And thou, O Love Second part verse 3:04 8 O Love, thou mortall speare First part full 2:52 9 If I by nature Second part full 2:30 10 Cupid, my prettie boy verse 2:52 11 Love is the peace verse 2:43 12 Selfe pitties teares full 3:48 13 Was ever man so matcht with boy? verse 2:21 14 O false and treacherous probabilitie verse 4:08 15 Man, dreame no more First part verse 1:43 16 The flood that did Second part verse 3:40 16 bis When thou hast swept Third part verse 17 Who trusts for trust First part full 3:40 18 Who thinks that sorrows felt Second part full 2:35 19 Man, dreame no more full 4:33 20 Farewell, sweet boye verse 3:01 21 Under a throne full 3:37 22 Where shall a sorrow First part verse 2:01 23 Dead, noble Brooke Second part verse 1:59 24 Where shall a sorrow (a6) First part full 2:48 25 Dead, noble Brooke (a6) Second part full 3:22 Editions by Richard Rastall: Martin Peerson, Complete Works IV: Mottects or Grave Chamber Musique (1630) (Antico Edition, 2012) -2- Martin Peerson and the publication of Grave Chamber Musique (1630) Martin Peerson’s second songbook, Mottects or Grave Chamber Musique , is known as a work of historical importance, but its musical and poetical importance is still unrecognised. -

Tallis to Whitacre Choral

Whitehall Choir CONDUCTOR Paul Spicer ••• ORGAN James Longford Tallis to Whitacre Choral TALLIS O Nata Lux BYRD HHææææcc Dies • Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis (from the GreatGreat ServicService)e) TOMKINS When David Heard WEELKES Alleluia GIBBONS O Clap Your Hands TAVENER Mother of God • Awed by the Beauty WHITACRE Nox Aurumque • Lux Aurumque Music for organ by BYRDBYRD,, PACHELBEL and PRPRÆÆÆÆTORIUSTORIUS Programme £2 Thursday, 24 November 2011, 7.30pm Church of St Alban the MartyrMartyr,, Brooke Street, Holborn, LoLondonndon EC1N 7RD P R O G R A M M E William Byrd Hæc Dies Eric Whitacre Lux Aurumque Thomas Tomkins When David Heard Michael Prætorius Two Variations on ‘Nun lob mein Seel den Herren’ (organ) William Byrd Magnificat Eric Whitacre Nox Aurumque INTERVAL Thomas Weelkes Alleluia. I heard a voice John Tavener Mother of God ThomasTallis O nata lux William Byrd Nunc dimittis John Tavener Awed by the beauty Johann Pachelbel Ciacona in D (organ) William Byrd Fantasia (organ) Orlando Gibbons O Clap your Hands The concert is expected to end at approximately 8.50pm. William Byrd (c.1540-1623) William Byrd was an English composer of the Renaissance. He wrote in many of the forms current in England at the time, including sacred and secular polyphony, keyboard and consort music. It appears from recent research that he was born in 1540 in London, and he was a pupil of Thomas Tallis. He also worked in collaboration with John Sheppard and William Mundy on one of his earliest compositions, a contribution to a joint setting of the psalm In exitu Israel composed for the procession to the font at the Paschal Vigil. -

Music for Voices and Viols La Spirita

Music for Voices and Viols La Spirita with guest artists Elizabeth Horn and Jack Zamboni Canzone Quarta Giovanni Gabrielli Canzone prima "La Spirita" (c.1556-1612) Melpomene Michael East (1580-1612) Fantazia no. 11 Henry Purcell (l659~ 1695) ** Though AmaryHis dance in green William Byrd (1543-1623) To ask for all thy love John Dowland Stay time a while thy flying John Dowland (1562~ 1626) ** Fantasia no. 7 John Coprario (c.1575-1626) A sad paven for these distracted tymes Thomas Tomkins February 14, 1649 (1572-1656) Prelude and Voluntary William Byrd Intermission I care not for these ladies Thomas Campi an ( 1566-1620) My love hath vowed Thomas Campian Go crystal tears John Dowland (arr. Will Ayton) Go crystal tears Will Ayton (1948- ) ** The Bee Anon. 171h c. Fall of the Leaf Marshall Barron (fl.2003 ) Yom Ze L'Yisrael Will Ayton The Cradle (Pavan) Anthony Holborne The Honie-suckle (Almaine) (d. 1602) The Fairie-round (Galliard We have chosen for this program some of our favorite music from the viola da gamba consort repertoire. The meat and potatoes of the viol consort is the English fantasia and we have included two fantasias in 4 parts by Henry Purcell and John Coprario. and one in 3 parts by Michael East. The fantasia (in all of its various spellings) was the most important instrumental form in late 16th and early 171h century England. Thomas Morley in 1597 described it thus: when a musician taketh a point at his pleasure, and wresteth and turneth it as he list, making either much or little ofit as shall seeme best in his own conceit. -

Thomas Morley Nine Canzonets and Music from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book Mp3, Flac, Wma

Thomas Morley Nine Canzonets and Music from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Nine Canzonets and Music from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book Country: US MP3 version RAR size: 1953 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1724 mb WMA version RAR size: 1583 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 875 Other Formats: AUD DXD DMF MP3 MP4 AC3 AHX Tracklist A1 –Thomas Morley Cruel, wilt thou persever 2:00 A2 –Thomas Morley False love did me inveigle 2:45 A3 –Thomas Morley My nymph the deer 1:24 A4 –William Byrd The Queen's Alman 2:32 A5 –Martin Peerson The Primerose 1:25 A6 –William Byrd La Volta 2:35 A7 –Thomas Morley Adieu, you kind and cruel 2:00 A8 –Thomas Morley Ay me! the fatal arrow 1:48 A9 –Thomas Morley Love took his bow and arrow 1:55 B1 –Peter Philips Galiarda dolorosa 3:56 B2 –Giles Farnaby Tell me, Daphne 1:30 B3 –William Byrd Galiarda 1:30 B4 –Thomas Morley O grief, even on the bud 1:48 B5 –Thomas Morley Lo, where with flower head 1:27 B6 –Thomas Morley Our Bonny-boots 1:17 B7 –John Bull Piper's Galliard 2:50 B8 –Martin Peerson The Fall of the Leafe 2:05 B9 –Giles Farnaby Tower Hill 0:35 Credits Bass Vocals – John Frost Contralto Vocals – Jean Allister Ensemble – The Ambrosian Consort Harpsichord – Valda Aveling Liner Notes – Denis Stevens Music Director – Denis Stevens Soprano Vocals – Patricia Clark Tenor Vocals – Edgar Fleet, Leslie Fyson Barcode and Other Identifiers Other (Library of Congress Catalog Card No.): 72-750084 Related Music albums to Nine Canzonets and Music from the Fitzwilliam Virginal -

Download Booklet

LIBERA NOS in some of the great Catholic houses. Byrd LIBERA NOS The Cry of the Oppressed employed the genre of the motet as his principal THE CRY OF THE OPPRESSED political tool. Among the most famous of these Music lamenting the destruction of Jerusalem works is Civitas sancti tui (published in his and captivity under a foreign power, or praying Cantiones sacræ collection of 1589), a poignant for the coming of a deliverer, was used to express lament for the ‘city made desolate’ in which Byrd the plight of Catholics in England and of the turns to stark and sombre chordal declamation 1 Civitas sancti tui William Byrd [5.02] Portuguese under Spanish rule in the late 16th for the phrase ‘Sion deserta facta est’ (‘Sion 2 Libera nos Thomas Tallis [2.08] and early 17th centuries. This recording explores has become a wilderness’). More daring in terms 3 Super flumina Babylonis Philippe de Monte [5.41] such musical ‘cries of the oppressed’ from of its message (and more dramatic in musical 4 Quomodo cantabimus William Byrd [8.38] opposite ends of Europe, which include some language) is Plorans plorabit: after weeping for 5 Sitivit anima mea Manuel Cardoso [4.22] of the most powerful works composed in England the captivity of ‘the Lord’s flock’, the speaker 6 Laboravi in gemitu meo Martin Peerson [5.29] and Portugal during this period. foresees the downfall of the king and queen. 7 Miserere mei Deus William Byrd [3.20] Byrd published the piece in his Gradualia of England’s most highly regarded composer of the 1605, and so the king and queen in question 8 Lachrimans sitivit anima mea Pedro de Cristo [5.54] period, William Byrd (1540–1623), gave voice are presumably to be identified as James I and 9 Plorans plorabit William Byrd [5.07] through his compositions to the suffering and Anne of Denmark. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. Among the many friends who provided support and encouragement are Clara, Carmen, Cibele and Marcelo, Hilda, Iker, James and Diana, Kydalla, Lynn, Maria-Carmen, Réjean, Vivian, and Yolo. -

Concert Program

Boston Early Music Festival in partnership with The Morgan Library & Museum presents Ensemble Correspondances Sébastien Daucé, conductor Lucile Richardot, mezzo-soprano Perpetual Night 17th-century Ayres and Songs Care-charming sleep Robert Johnson (ca. 1583–1633) Go, happy man John Coprario (ca. 1570/80–ca. 1626) Whiles I this standing lake William Lawes (1602–1645) O precious time Martin Peerson (1571/73–1651) Music, the master of thy art is dead Lawes No more shall meads Nicholas Lanier (1588–1666) Suite No. 2 in C major Matthew Locke (1621/23–1677) Pavan Give me my lute John Banister (1624/25–1679) Howl not, you ghosts and furies Robert Ramsey (d. 1644) Britanocles the great and good appears Lawes Suite No. 1, Consort of 4 parts Locke Ayre — Courante Powerful Morpheus, let thy charms William Webb (ca. 1600–1657) Rise, princely shepherd John Hilton (1599–1657) Amintas, that true hearted swain Banister Poor Celadon, he sighs in vain (Loving above himself) John Blow (1649–1708) When Orpheus sang Henry Purcell (1659–1695) Phillis, oh! turn that face John Jackson (d. 1688) Epilogue: Sing, sing, Ye Muses Blow Saturday, April 24, 2021 at 8pm Livestream broadcast Filmed concert from Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, Paris, France BEMF.org Ensemble Correspondances Lucile Richardot, mezzo-soprano Caroline Weynants & Deborah Cachet, soprano Davy Cornillot, tenor Nicolas Brooymans, bass Lucile Perret, recorders Béatrice Linon & Josèphe Cottet, violin Mathilde Vialle, Étienne Floutier & Mathias Ferré, viola da gamba Thibaut Roussel & Diego Salamanca, theorbo & lute Angélique Mauillon, harp Arnaud de Pasquale, virginal Sébastien Daucé, organ, virginal & conductor Vincent Huguet, artistic collaboration Ensemble Correspondances is in residence at the Théâtre de Caen. -

'Tis Nature's Voice: Music and Poetry in Anticipation of Spring

The Western Early Keyboard Association Presents ‘Tis Nature’s Voice: Music and Poetry in Anticipation of Spring Jillon Stoppels Dupree, harpsichord Carla Valentine Pryne, poetry Saturday, February 18, 2017 - 2 p.m. Reed College, Performing Arts Building, Room 320 From “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey,” 1798 William Wordsworth (1770-1850) The Fall of the Leafe Martin Peerson (ca.1572-1651) The Leaves bee Greene William Inglott (1554-1621) The Primrose Martin Peerson “Trees” (The Compass Flower, 1977) W.S. Merwin (1927 - ) The Nightingale Anonymous (17th century, England) Onder een Linde Groen Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621) “Morning in a New Land” (New and Selected Poems, 1992) Mary Oliver (1935 - ) Sheep May Safely Graze (arr. J.S. Dupree, Cantata BWV 208) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) From “Nature” (Essay VI, 1836) Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) Forest Music: Allegro, Gigue George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) “The Call of Two Birds” Matsuo BashÇ (1644-1694) Le Coucou Louis-Claude Daquin (1694-1772) Capriccio sopra il Cucu Johann Kaspar Kerll (1627-1693) INTERMISSION From “Specimen Days” (Prose Works, Complete, 1892) Walt Whitman (1819-1892) Le Moucheron François Couperin (1668-1733) La Gazoüillement François Couperin “The Selbourne Nightingale” (Springtime in Britain, 1970) Edwin Way Teale (1899-1980) Le Rossignol-en-amour François Couperin La Linote-éfarouchée François Couperin Les Fauvétes Plaintives François Couperin La Poule Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) From “Wilderness Letter,” 1960 Wallace Stegner (1909-1993) Les Tourbillons Jean-Philippe Rameau “So, friends, every day do something” (Earth Prayers from Around the World, Wendell Berry (1934 - ) ed. Elizabeth Roberts and Elias Amadon, 2009) Le Rappel des Oiseaux Jean-Philippe Rameau Jillon Stoppels Dupree Described as “one of the most outstanding early musicians in North America” (IONARTS) and “a baroque star” (Seattle Times), harpsichordist Jillon Stoppels Dupree has captivated audiences internationally.